“A Spanish version of EastEnders”: a reception study of a telenovela subtitled using MT

Ana Guerberof-Arenas, University of Groningen

Joss Moorkens, SALIS/ADAPT Centre, Dublin City University

David Orrego-Carmona, University of Warwick and University of the Free State, Bloemfontein

ABSTRACT

This article presents the results of three AVT reception experiments with over 200 English-speaking participants who watched a 20-minute clip of a Mexican telenovela in three different translation modalities: human-translated (HT), post-edited (PT) and machine-translated (MT). Participants answered a questionnaire on narrative engagement, enjoyment, and translation reception of the subtitles. The results show that viewers have a higher engagement with PE than HT, but there is only a statistically significant difference when PE is compared to MT. When it comes to enjoyment, the differences are more pronounced, and viewers enjoy MT significantly less than PE and HT. Finally, in translation reception, the gap is even more pronounced between MT vs. PE and HT. However, the high HTER scores demonstrate that a substantial amount of edits are necessary to render the automatic MT subtitles publishable. It is not clear that results would be comparable were subtitlers not given sufficient time or remuneration for the post-editing task.

Keywords

AVT, subtitling, machine translation post-editing, engagement, enjoyment, translation reception, HTER.

1. Introduction

In the wake of successful translated series such as Squid Games and Money Heist, the media has drawn attention to controversies regarding the production of subtitles (Groskop 2021; Lange 2021). The use of MT for subtitling alongside reduced remuneration and restrictive work practices has become highly controversial, causing concerns about sustainability. Reports of a “talent crunch” as translators exit the industry come at a time when entertainment platforms are very successful. Companies maintain that low remuneration is not the reason for the shortage of professionals (Iyuno SDI Group 2022) while in the ELIS 2022 survey (ELIS 2022) respondents suggest that better rates and salaries could help tackle the shortage issue. The European Federation of Audiovisual Translators, AVTE, published a Machine Translation Manifesto (AVTE 2022) that proposes best practices when using MT, while the French (ATAA 2021) and the Spanish Associations of Audiovisual Translators (ATRAE 2021) have released statements urging content producers not to use MT post-editing (PE), but rather to rely on human translators (HT).

It is, therefore, of utmost importance to know how and when to use MT in the AVT sector, where translation is becoming multidirectional1. Recent studies on AVT investigate the gains in productivity and the improving quality of subtitles translated using MT, and concluding that this is a viable solution, given the appropriate quality conditions (Bywood, Georgakopoulou, and Etchegoyhen 2017; Matusov, Wilken, and Georgakopoulou 2019; Koponen et al. 2020a ). Additionally, studies have explored subtitlers’ satisfaction with PE (Koponen et al. 2020b; Karakanta et al. 2022). However, there is currently no research that looks at the impact of MT in the translation workflow on the viewer of audiovisual content.

In this article, we seek to fill this gap by looking at the reception of subtitles translated into different modalities. Based on a methodology already tested on literary translation (Guerberof-Arenas and Toral 2020), we set up three experiments to measure the narrative engagement (Busselle and Bilandzic 2009), enjoyment (Hakemulder 2004) and translation reception of subtitles (the viewers’ opinion on the translation and the language) from a clip of a Mexican telenovela translated into English in three different modalities: HT, PE and MT. In the following sections, we firstly review the state of the art, secondly, we present the methodology used and the participants’ profile, thirdly, we analyse the results obtained from over 200 English-speaking participants in three experiments, and finally, we reflect on the use of MT in this type of content, and indicate future lines of research.

2. AVT reception and machine translation

AVT research has devoted a significant amount of attention to reception due to the constrained nature of AVT, the high relevance of viewers, and the widespread use of subtitling for entertainment and language learning. Since the 1980s, researchers have been looking at subtitle reading, particularly using eye-tracking methods (d’Ydewalle, Muylle, and van Rensbergen 1985; d’Ydewalle, Rensbergen, and Pollet 1987). With the increasing interest in reception, the scope of AVT studies widened to include qualitative and mixed-methods research designs to provide a more comprehensive understanding of viewers’ engagement (Orrego-Carmona 2018).

Subtitle reception studies have shown different layers of engagement and provided information on viewers’ processing and reactions. For example, eye-tracking studies have shown that viewers are not too sensitive to subtitles overlapping shot changes (Szarkowska, Krejtz, and Krejtz 2017) and that poor segmentation might affect reading but do not seem very relevant for comprehension (Perego et al. 2010; Rajendran et al. 2013; Gerber-Morón, Szarkowska, and Woll 2018). However, when asked about their preferences, viewers have a clear preference for syntactically segmented subtitles (Gerber-Morón, Szarkowska, and Woll 2018) and identified segmentation as a major problem with automatic/MT subtitles (Koponen et al. 2020a).

With the growing use of MT in subtitle production (Koponen et al. 2020b; Karakanta et al. 2022), it becomes essential to explore how viewers respond to MT and PE subtitles in contrast with HT subtitles. Ortiz Boix (2016) examined two conditions (HT and PE) for voice-over translation of wildlife documentaries. The results of a panel of experts and 56 end users established no significant differences between the two conditions. Hu, O’Brien, and Kenny (2020) compared the comprehension of and attitude towards PE, MT, and HT subtitles for MOOCs. In this experiment, the HT subtitles were prepared by a non-professional translator and the PE subtitles were post-edited by a professional. Hu and colleagues found that the PE condition scored highest in their reception metrics, and that participants had a positive attitude towards all subtitles, regardless of production conditions.

3. Combined methods to measure reception

To explore the translation of subtitles in different modalities, we focus on narrative engagement, enjoyment, comprehensibility, and reception (Guerberof-Arenas and Toral 2020) when viewing a 19’ 26” clip from Episode 55 of the Mexican telenovela Te doy la vida (Cataño and Acosta, 2020). The programme is a drama/soap opera that reveals the relationships, loyalties, and enmities between family members centred around a car workshop in Mexico. The telenovela was previously chosen for a comparative test between AppTek and Google Translate for subtitling, with AppTek being the preferred system (Santilli 2021). The clip for the current study was also provided by AppTek2, who also kindly provided the Latin-American Spanish to English MT output from their AVT-customised neural system. Since the data suggested that the AppTek engine performed better than Google Translate and we could avail of a “real” clip, the decision was made to test using this telenovela.

3.1 Changes in the design through the pilot studies

In order to refine our methodology, we conducted two pilot studies to compare the reception of HT, MT, and PE subtitles. AppTek also provided the first version of the HT subtitles by a highly experienced translator based in Argentina and we engaged a Colombia-based subtitler to post-edit the MT3. Details of the results of these pilot studies are presented in Section 4. Based on these pilot studies, some changes were made to the methodology: most pertinently, the translation and PE were redone as described in Section 3.2. In addition, the first post-editor made substantial changes to spotting that we felt would be restricted in a subtitling workflow due to the widespread use of templates (Oziemblewska and Szarkowska 2022). We therefore amended the PE guidelines to limit spotting changes.

3.2 Preparation of translations and video files in the main experiment

In preparation for translation and PE, two SRT subtitle files were created. File 1 contained the source text in ES-MX to be translated into English (subtitles 1 to 182) and MT to be post-edited (subtitles 183 to 357). File 2 had the reversed order. Two translators with similar experience and language profiles used the tool Ooona, a cloud-based tool (García-Escribano, Díaz-Cintas, and Massidda 2021) to complete the project. The translators were paid at their requested rate. They both received the video, full source text subtitles and the prepared “Pretranslated-Target” file. Guidelines for translation and PE (of publishable quality) are in Appendix A4. Once the target SRT files were received, the final HT, PE, and MT subtitles were assembled (File 1 and File 2 from each translator were split according to the modality in which they were processed) and a video file with embedded subtitles was created for each condition. This meant that the HT and PE versions were translated and post-edited by the same two translators, guaranteeing that a preference for HT or PE was not due to a preference for the style of a given translator. The MT version was the original output received from AppTek.

3.3 Measuring MT subtitle quality using HTER

The Human-targeted Translation Edit Rate (HTER; Snover et al. 2006), metric was used to measure the number of PE edits5, with an overall value 44.236 for the whole clip (40.46 for Translator A, 47.21 for Translator B), demonstrating that the translators performed a high number of edits to render the subtitles publishable7. In professional settings, this would have repercussions for remuneration if PE payment rates are reduced on the basis that MT requires little correction. According to Parra Escartín and Arcedillo (2015), a HTER of 20.98 represents a discount equivalent to a 75-84% fuzzy match in a translation memory. More than double this level of editing was required in this study for translators to produce publishable subtitles. Further, large corporations using TER to pay post-editing suggest that values above 30 are not acceptable for use without editing (Schmidtke and Groves 2019) and from industry experience, we are aware that post-editing work with HTER above 40 is usually paid at the full rate (similar to a 0% match from translation memory).

Here are some examples of the issues found in the MT output sent to the subtitlers:

A) Proper noun errors in the MT output: named entity recognition is a known challenge for MT development. For example, the HT retains the original restaurant name in the segment “How about Las Tortas del Finito?”, the MT output reads “It could be the finite cakes”.

B) Gender: inconsistent use in the MT segments, e.g., “- She’s a romantic woman. He loves the messages I send him.” The HT for this segment is “She’s a romantic. She loves the texts I send her.” Note also the extra dash, included in 183 MT segments.

C) Issues with sarcasm, e.g., the MT “Oh, no, man. As always, him, splendid.” and HT “No way, man. Mr. Generous, as always.”

D) Idioms are another issue, e.g. the source segment “Este arroz ya se coció.” appears as “This is a done deal.” in the HT and PE, but “This rice is already cooked.” in the MT.

E) MT occasionally changes the meaning, as in the segment “And you have no idea how much it hurts to sacrifice me.” which, when post-edited, became “You have no idea how much it hurts me to make this sacrifice.”

F) Risky or offensive MT output, e.g. when the HT is “Dazzle her with a nice restaurant.” and the MT produced “You beat her up with a nice restaurant.”

Some preferential changes were also introduced as a result of PE, for example where the MT and HT reads “Well you’ll have to learn.”, the PE reads “Well, you’ll have to learn how.” There are also examples of changes to spotting in PE, despite guidelines to the contrary. The PE output tended to retain non-standard commas at the end of some subtitles from MT output, and once, italics were added, as in the following example (indicated by the tags <i> and </i>):

HT: I made quesadillas. Are you hungry?

PE:I made<i> sincronizadas. </i>Are you hungry?

MT: I did sync, are you hungry?

This change from sincronizadas to quesadillas is not the only example of domestication in the HT: elsewhere, tacos are surprisingly replaced by “lunch” despite tacos being a commonly used food term outside of Mexico. However, in general, the HT and PE conditions both largely conform to our participants’ expectations, as may be seen in Section 4. A segment-by-segment analysis of subtitle quality is beyond the scope of this study, but the quality of both HT and PE appear to be satisfactory as judged by the participants.

3.3.1 Subtitlers’ post-task questionnaire

One of the translators responded to our subtitlers’ post-task questionnaire with some positive views on post-editing8. She recognises it can be faster than translating from scratch but does not think this applies to the translation of subtitles. She wrote:

Although post-editing speeds up my work, I don’t find it as enjoyable as translating from scratch. I also don’t think it’s easier than translating from scratch. There are specific types of projects where I prefer to use post-editing [rather] than translate from scratch, but subtitling dialogue isn’t one of them. The language is inherently colloquial and that just doesn’t work very well with MT in my opinion.

Regardless of this, the translator stated she was extremely satisfied with the results of her HT and PE tasks.

3.4 Viewing conditions

Unbeknown to them, all viewers were randomly assigned a condition. WATCHA corresponded to the telenovela with PE subtitles, WATCHB to MT subtitles, and WATCHC to the HT condition. In this article, we use PE, MT and HT for continuity.

3.5 Questionnaire

An online questionnaire in English was distributed to participants using Qualtrics (www.qualtrics.com). Participants were told that they would watch a Mexican telenovela and fill in a user experience questionnaire. After this, the participants first read the information brochure and consent form and, if they decided to participate in the experiment, they were taken to the following sections9:

3.5.1 Demographics and Viewing Frequency

This section contains 11 questions on demographics and viewing patterns (e.g. “How often have you watched a programme with subtitles in the last 24 months? How much do you enjoy watching television programmes with subtitles?”, “How many subscriptions to streaming platforms do you have?”)

3.5.2 Comprehension Questions

After watching the clip, the participants answered 10 four-choice questions to ensure basic comprehension. There was no minimum number of correct answers to continue because we wanted to analyse comprehension with the full range of responses (1 to 10) depending on the modality.

3.5.3 Narrative Engagement

Participants were then presented with a 12-item Narrative Engagement scale (Busselle and Bilandzic 2009) with 7-point Likert-type responses. The questionnaire includes four categories: Narrative understanding (e.g., “At points, I had a hard time making sense of what was going in the programme.”), Attentional focus (e.g., “I found my mind wandering while the programme was on.”), Narrative presence (e.g. “The programme created a new world, and then that world suddenly disappeared when the programme ended.”), and Emotional engagement (e.g., “I felt sorry for some of the characters in the programme.”).

3.5.4 Enjoyment

Participants were then asked to answer two questions to address enjoyment: “How much did you enjoy watching the clip?”, “Would you recommend this clip to a friend?” (Dixon et al. 1993; Hakemulder 2004).

3.5.5 Translation reception

This was a 7-item scale to measure the reception of the translated subtitles (e.g. “How easy were the subtitles to understand?”, “I thought the subtitles were very well written”, “I found words or sentences that were difficult to understand.”). Participants were asked to use a 7-point Likert-type scale to rate these questions/statements (Guerberof-Arenas and Toral 2020).

3.5.6 Debriefing and payment questions

At the end of the questionnaire, participants were debriefed on the nature of the research. Only then were they informed about the translation modality assigned (either MT or PE or HT). Following this, and only if their modality was MT, they were asked to rate the quality of the MT, and to indicate their translation preference.

3.6 Qualtrics and Prolific

As mentioned, Qualtrics was used to create the questionnaire. For the pilot study, the questionnaire was distributed through several social media channels (i.e., Twitter, LinkedIn, and Facebook groups). However, since this process did not generate a satisfactory number of participants and since posting in the researchers’ social media skewed the results, for the main experiment, we decided to use an existing platform that provides a base from which to gather research participants and pay for experimental research.

Prolific (www.prolific.com) allowed us to post the Qualtrics questionnaire while at the same time specifying the participant profile. Our screening conditions consisted of location in the UK (to avoid language variation), English as a mother tongue (to avoid language understanding variation), and at least one subscription to a streaming platform (to avoid participants who do not watch audiovisual content but are looking for payment). After the pilot studies, we refined our profile due to non-compliance and added: exclusion of participants in the previous studies, a 100% approval rate in the platform, which means that the participants’ performance in previous studies was always approved by researchers, and a minimum of 15 and maximum of 150 submissions in the platform, which meant that participants had sufficient experience working in the platform. Although payment was to the platform and not to participants directly, we were informed that the participants were paid an average of 9 sterling pounds per hour (the average duration was around 35 minutes).

Although we found the platform very effective, and it allowed us to discard those participants who did not meet the criteria or did not fully complete the experiment, some participants in these platforms engage as part of a job and are not occasional contributors who participate in an experiment out of personal interest while receiving a practically nominal fee. We feel that this motivation is an important consideration. However, because of the nature of this particular experiment (we are looking for a wider audience that avails from a standard type of entertainment) we consider the results to be valid and generalizable.

3.7 Calendar and process for the projects

Table 1 shows the time periods for the three project iterations, the platforms, the number of participants, and their distribution:

| Project | Date | Platform | Participants | Distribution of participants |

| Pilot | 25/02-04/04/22 | Qualtrics & social media | 23 | 8 PE, 6 MT, 9 HT |

| Prolific Pilot | 05/05/22 | Qualtrics & Prolific | 74 | 23 PE, 23 MT, 28 HT |

| Main Prolific | 09/09-01/10/22 | Qualtrics & Prolific | 119 | 40 PE, 38 MT, 41 HT |

Table 1: Calendar, platforms and participants

4. Reception of a Mexican telenovela

Since we conducted three iterations, we first summarise the results for the two pilot experiments, and the issues encountered, indicating the motivation for each new phase and the improvements made. We then present the results for the main experiment, which has the highest number of participants and the most refined experimental design.

4.1 Summary of the pilot experiment using social media

Since the engagement methodology had previously been successfully used with literary texts, we ran a pilot experiment using snowball sampling, distributed via social media. Twenty-three participants (17 female and 6 male), between 18 and 44 years old, participated in the pilot. Native languages were mostly English, with two Italian speakers and one speaker each of Spanish, Portuguese, and Dutch. 16 had professions related to language and 9 unrelated. 15 participants had moderate-to-little knowledge of Spanish and 8 had a high level or were bilingual. Table 2 shows a summary of the findings using a mean value10. Values for all categories other than Comprehension range from one (strongly disagree) to seven (strongly agree). The Comprehension figure is the number of questions answered correctly from a total of ten.

| Modality | Narrative Engagement | Enjoyment | Translation Reception | Comprehenson (of 10 questions) | Viewing patterns |

| PE | 3.70 | 3.81 | 4.88 | 8.13 | 3.75 |

| MT | 3.29 | 3.67 | 3.43 | 7.00 | 3.50 |

| HT | 4.76 | 4.83 | 5.58 | 7.78 | 4.33 |

Table 2: Mean values per variable in pilot experiment

HT has the highest values for Narrative Engagement, Enjoyment, and Translation Reception, but also the highest preference for programmes with subtitles among participants. We found that participants were able to follow the questionnaire, watched the video (except in certain cases depending on the browser), and responded easily to the questionnaire. However, there are many issues with the data, the most important perhaps that few participants had English as their mother tongue. The second issue was that the majority of participants had professions related to language (because the questionnaire was distributed by the researchers). This meant that they were accustomed to subtitles and they were perhaps more strict when it came to judging translations. After this initial experiment, we decided to use the Prolific platform.

4.2 Summary of pilot experiment in Prolific

In this next pilot experiment, our main aim was to test the Prolific platform. In this first instance, 74 participants (57 female, 16 male and 1 non-binary), between 18 and 54 years old with English (UK) as their mother tongue, took part. Seventy-three had no knowledge, a little or moderate knowledge of Spanish and one had Very good knowledge. Only five had a profession related to language.

Table 3 shows a summary of the findings using a mean value to illustrate each category. In this case, because the number of participants was higher, we ran a Kruskal-Wallis H11 test for non-parametric data and post-hoc comparisons using the Conover-Iman test with the Holm-Bonferroni correction. These results are shown in the row Significance12. Again, ranges are from one to seven other than one to ten for Comprehension.

| Modality | Narrative Engagement | Enjoyment | Translation Reception | Comprehension | Viewing patterns |

| PE | 4.2 | 4.63 | 5.83 | 7.26 | 3.20 |

| MT | 3.82 | 3.78 | 3.86 | 7.00 | 2.5 |

| HT | 4.05 | 3.96 | 5.43 | 7.53 | 3.16 |

| Significance | No | No | Yes PE / MT MT / HT |

No | Yes No differences between modalities |

Table 3: Mean values per variable in Prolific pilot experiment

PE has the highest values in Narrative Engagement, Enjoyment and Translation Reception, but also viewers reported the highest preference for programmes with subtitles. However, there are no significant differences between the modalities except in Translation reception, where participants ranked PE significantly more than MT (Z = 7.45; p = .00) and MT significantly less than HT (Z = -5.81; p = .00)13. We also see that the viewing frequency of participants in the MT modality is lower, and there are significant differences overall, but post-hoc comparisons show no significant differences.

When looking at the results, we considered that the translator could be a confounding variable as the PE and HT subtitles were created by different subtitlers. We amended the methodology for the main experiment so that this was accounted for and recruited a larger cohort of participants to avoid different viewing frequencies.

4.3 Main experiment

In the main experiment, a larger cohort of 119 participants was presented randomly with PE, MT or HT subtitles; they provided valid responses to the questionnaire14.

4.3.1 Participants

Table 4 shows a summary of the demographics and characteristics of this group.

| Categories | |||||

| Gender | Women | Men | Non-binary | Prefer not to say | Total |

| 70 | 47 | 2 | 0 | 119 | |

| Age | 18-34 | 25-34 | 35-44 | 45-54 | Total |

| 46 | 60 | 12 | 1 | 119 | |

| Studies | Secondary | Some college | BA/MA/PhD | Professional | Total |

| 21 | 30 | 66 | 2 | 119 | |

| Level of Spanish | No knowledge | A little | A moderate amount | Very good knowledge | Total |

| 59 | 53 | 6 | 1 | 119 | |

| Profession | Language related | Other | Total | ||

| 11 | 73 | 84 and 35 blanks | |||

Table 4: Demographics of participants in main experiment

Participants are mostly women aged 18 to 34 with tertiary education, little or no knowledge of Spanish, and whose work is not related to languages. We were curious to know if there was an uneven distribution of language-related work per condition, as this could account for a different user experience. A Chi-Square test revealed no significant differences between these groups.

4.3.2 Comprehension questions

Table 5 shows the descriptive statistics for the comprehension questions per condition. No minimum number of correct responses was set for participants to be able to continue the questionnaire.

| Condition | N | mean | SD | median | min | max | range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PE | 40 | 7.65 | 1.87 | 8 | 3 | 10 | 7 |

| MT | 38 | 6.92 | 1.84 | 7 | 2 | 10 | 8 |

| HT | 41 | 8.02 | 1.93 | 8 | 1 | 10 | 9 |

Table 5: Descriptive values for comprehension questions

If we consider the mean and median values, participants perform better in the HT and PE condition, although the MT condition does show mean values above 5, i.e. more than half of the questions were answered correctly. The variable Comprehension was explored according to the translation condition of the subtitles using the Kruskal-Wallis test. Statistically significant differences were found between conditions (H(2) = 9.59, p < .01) with a mean rank score of 69.70 for HT, 62.33 for PE and 47.09 for MT. Post-hoc comparisons show statistically significant differences between MT and HT (Z = 3.06; p = .00) but not between PE and MT. Therefore we can say that the condition HT was a factor in participants responding correctly to a higher number of questions if compared with MT, but not with PE.

4.3.3 Viewing frequency

Based on the pilot experiments, we wanted to check if the viewing frequencies among participants differ across translation conditions, as this might affect other variables such as engagement, enjoyment or even translation reception. It is preferable if these frequencies are balanced among the viewers in the three conditions.

Two questions addressed this variable: “How often have you watched a programme with subtitles in the last 24 months?” and “How much do you enjoy watching television programmes with subtitles? Please consider the last 24 months”. The participants had to rank the responses from 1 (Never) to 5 (Daily). The Viewing_frequency variable was then the average value of these two questions.

| Condition | N | mean | SD | median | min | max | range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PE | 40 | 3.35 | 0.99 | 3 | 1.5 | 5 | 3.5 |

| MT | 38 | 3.07 | 0.98 | 3 | 1.5 | 5 | 3.5 |

| HT | 41 | 3.29 | 1.02 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 4 |

Table 6: Descriptive values for viewing frequency

As we can see from the descriptive statistics in Table 6, the values for each condition are very similar. A Kruskal-Wallis test shows no significant differences between conditions if we consider the variable Viewing_frequency, meaning that the results for the variables of interest are not confounded by the participants’ viewing patterns.

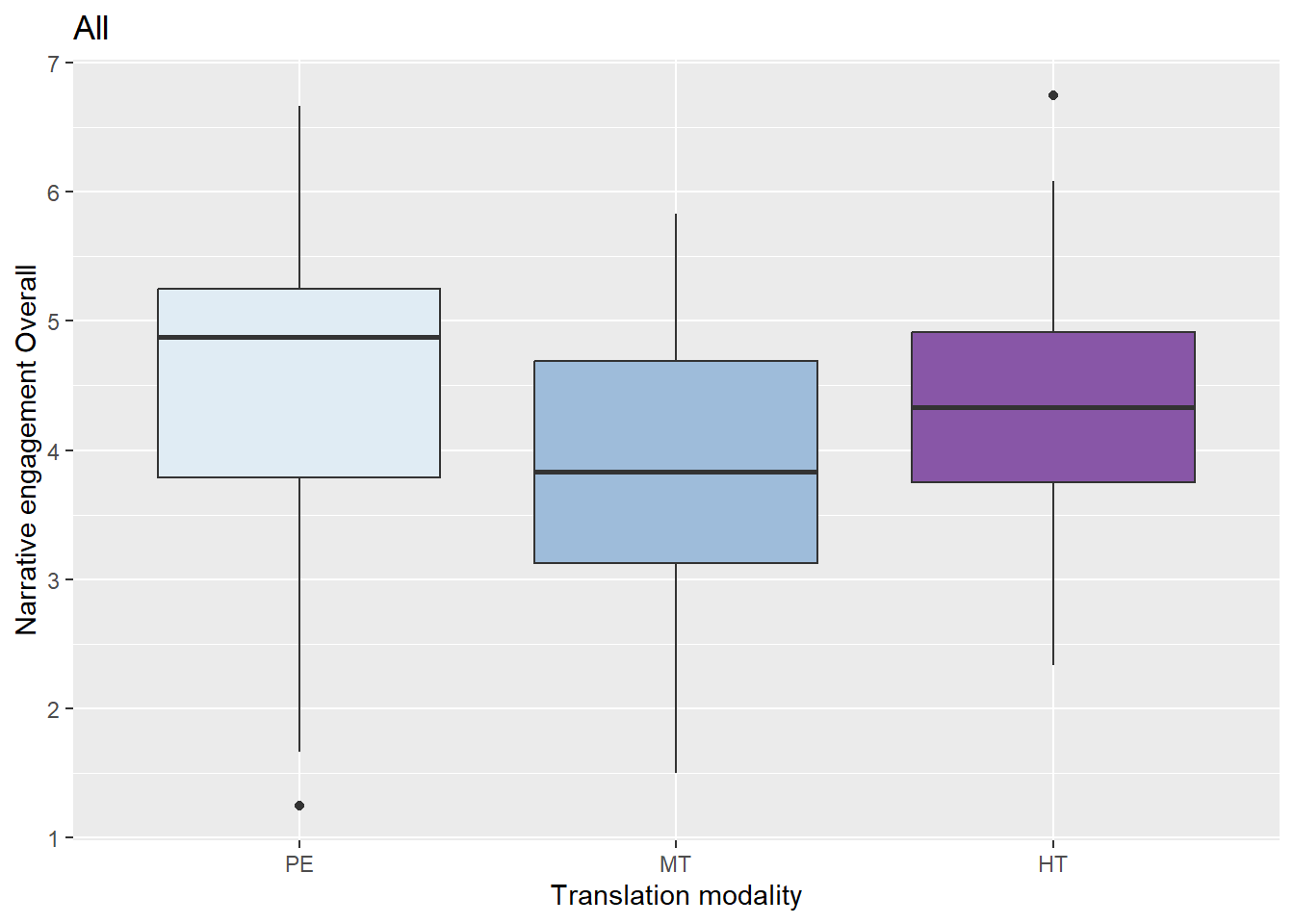

4.3.4 Narrative engagement

We calculated the average value for the 12-item Narrative Engagement scale presented to the participants. Figure 1 shows these results (N = 119). The Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient (α)15 is 0.90 for all the items in the scale, which is considered an excellent reliability score.

Figure 1 Narrative engagement per modality in the main experiment

Figure 1 shows that the narrative engagement overall is highest for PE, followed by HT and lastly by MT, i.e. viewers report higher engagement when watching the telenovela with PE subtitles. These results are similar to the pilot experiment in Prolific.

To understand the data better, firstly, the variable Narrative_Engagement was explored according to the translation condition of the subtitles using the Kruskal-Wallis test. Statistically significant differences were found between conditions (H(2) = 9.29, p < .01) with a mean rank score of 71.68 for PE, 59.910 for HT and 47.84 for MT. Post-hoc comparisons show statistically significant differences between PE and MT (Z = 3.15; p = .00) but not between HT and MT. Secondly, and since viewers had different viewing patterns, we ran a linear regression model16 to see the interaction between the dependent variable Narrative_Engagement and the independent variables Modality and Viewing_frequency. A significant regression was found (F(3,115) = 7.90, p<0.00), with an R squared of 0.15. The estimated mean for PE was 3.37, the predicted narrative engagement decreases by 0.62 points in MT and 0.28 in HT and increases by 0.37 according to the viewing frequency. MT and the viewing frequency are statistically significant.

Therefore, viewers that watch subtitles that are post-edited have engaged significantly more than those with MT subtitles, also those that have watched programmes with subtitles and enjoyed them more in the last 24 months have a statistically significant higher engagement than those who have a lower viewing frequency.

Narrative engagement per category

The Narrative Engagement scale contains four distinct categories. Narrative Understanding relates to the ease of comprehension of a programme. Participants ranked their agreement with the following statements from 1 to 7: “At points, I had a hard time making sense of what was going on in the programme”, “My understanding of the characters is unclear”, “I had a hard time recognizing the thread of the programme”. There were significant differences between modalities in this category. The Kruskal-Wallis test shows statistically significant differences between conditions (H(2) = 10.66, p < .00). Post-hoc comparisons show statistically significant differences between PE and MT (Z = 3.38; p = .00) but no statistically significant differences between HT and MT, nor PE and HT.

Attentional Focus is the state of being engaged and not distracted. Participants reacted to the following statements: “I found my mind wandering while reading the programme”, “While reading, I found myself thinking about other things”, “I had a hard time keeping my mind on the programme”. There are no statistically significant differences in this category.

Narrative Presence is the feeling that one has entered the world of the programme. Participants reacted to these statements: “During the reading, my body was in the room, but my mind was inside the world created by the programme”, “The programme created a new world, and then that world suddenly disappeared when the programme ended”, “At times during the reading, I was closer to the situation described in the programme than the realities of here-and-now”. The Kruskal-Wallis H test shows statistically significant differences between conditions (H(2) = 7.65, p < .02). Post-hoc comparisons show statistically significant differences between PE and MT (Z = 2.65; p = .01) but not between HT and MT, nor PE and HT.

Emotional Engagement is feeling for and with the characters. Participants reacted to these statements: “During the narrative, when a main character suffered, I felt sad”, “The programme affected me emotionally”, “I felt sorry for some of the characters in the programme”. There are no statistically significant differences in this category.

The categories affected by the use of MT are Narrative Understanding (the ease of comprehension of the programme), as in previous research with literary texts (Guerberof-Arenas and Toral 2020), but also Narrative Presence (the feeling of immersion in the programme). It appears MT has a disconnecting effect for viewers of this telenovela that does not happen in the HT or PE conditions.

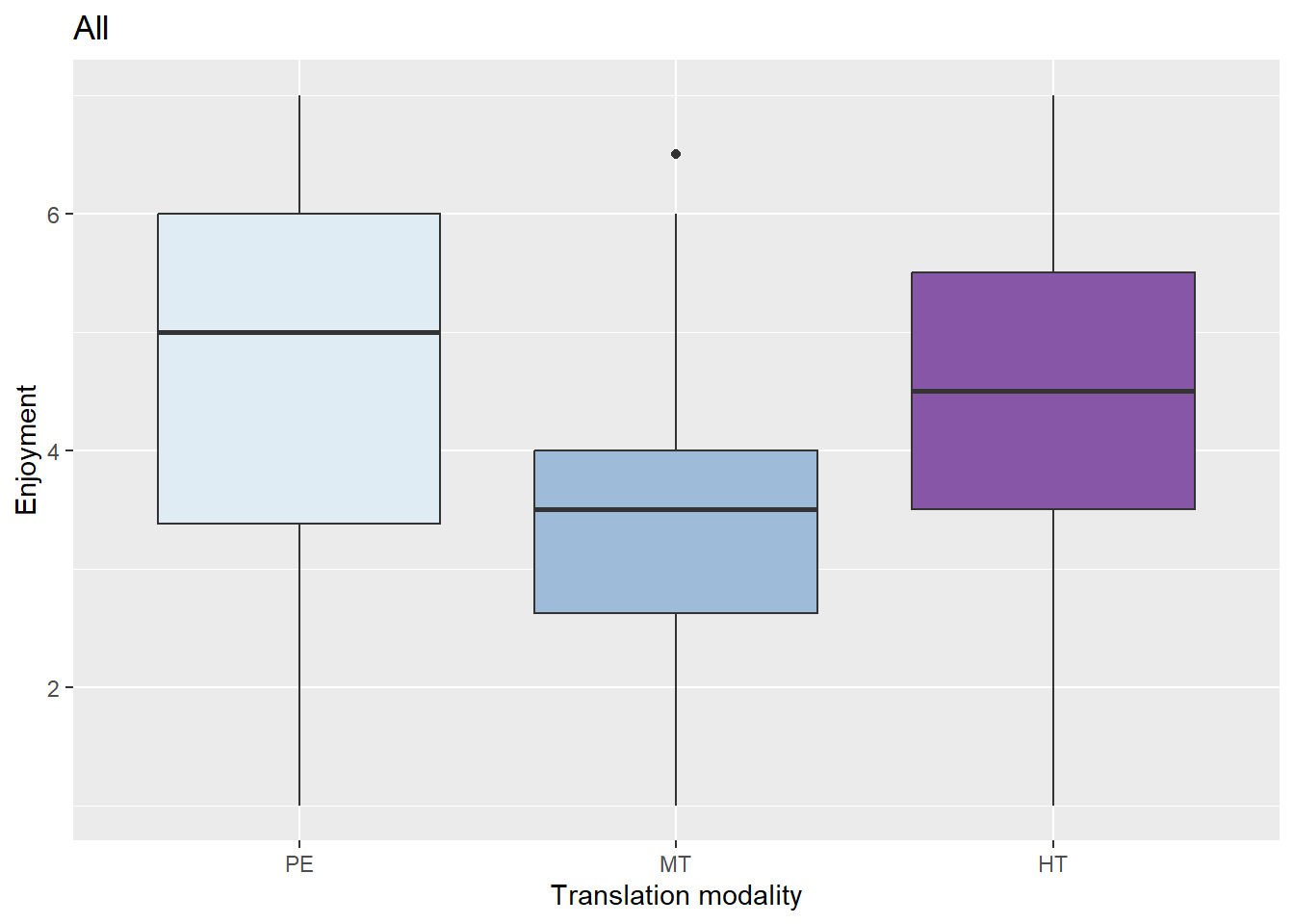

4.3.5 Enjoyment

Figure 2 shows the results of the average scores given for this 2-item scale (α = 0.83) for the two languages (N = 119).

Figure 2: Enjoyment according to modality in the main experiment

Figure 2 shows that differences between conditions are more pronounced than in narrative engagement. Therefore, and as before, we look at the variable Enjoyment according to the translation condition using the Kruskal-Wallis test. Statistically significant differences were found between conditions (H(2) = 10.03, p < .01) with a mean rank score of 69.48 for PE, 63.88 for HT and 45.84 for MT. Post-hoc comparisons show statistically significant differences between PE and MT (Z =3.15; p = .00) and between MT and HT (Z = -2.48; p = .02).

We ran a linear regression model to see the interaction between the dependent variable Enjoyment based and the independent variables Modality and Viewing_frequency. A significant regression was found (F(3,115) = 9.35, p<0.00), with an R squared of 0.18. The estimated mean for PE was 2.70, the predicted Enjoyment decreases by 0.90 points in MT and 0.25 in HT and increases by 0.57 according to the viewing frequency. MT and the viewing frequency are of significant value.

Therefore, we can say that viewers who view post-edited or translated subtitles enjoy the telenovela significantly more than those with MT subtitles. We also see that those who have watched programmes with subtitles and enjoyed them more in the last 24 months have a statistically significantly higher enjoyment than those that have a lower viewing frequency.

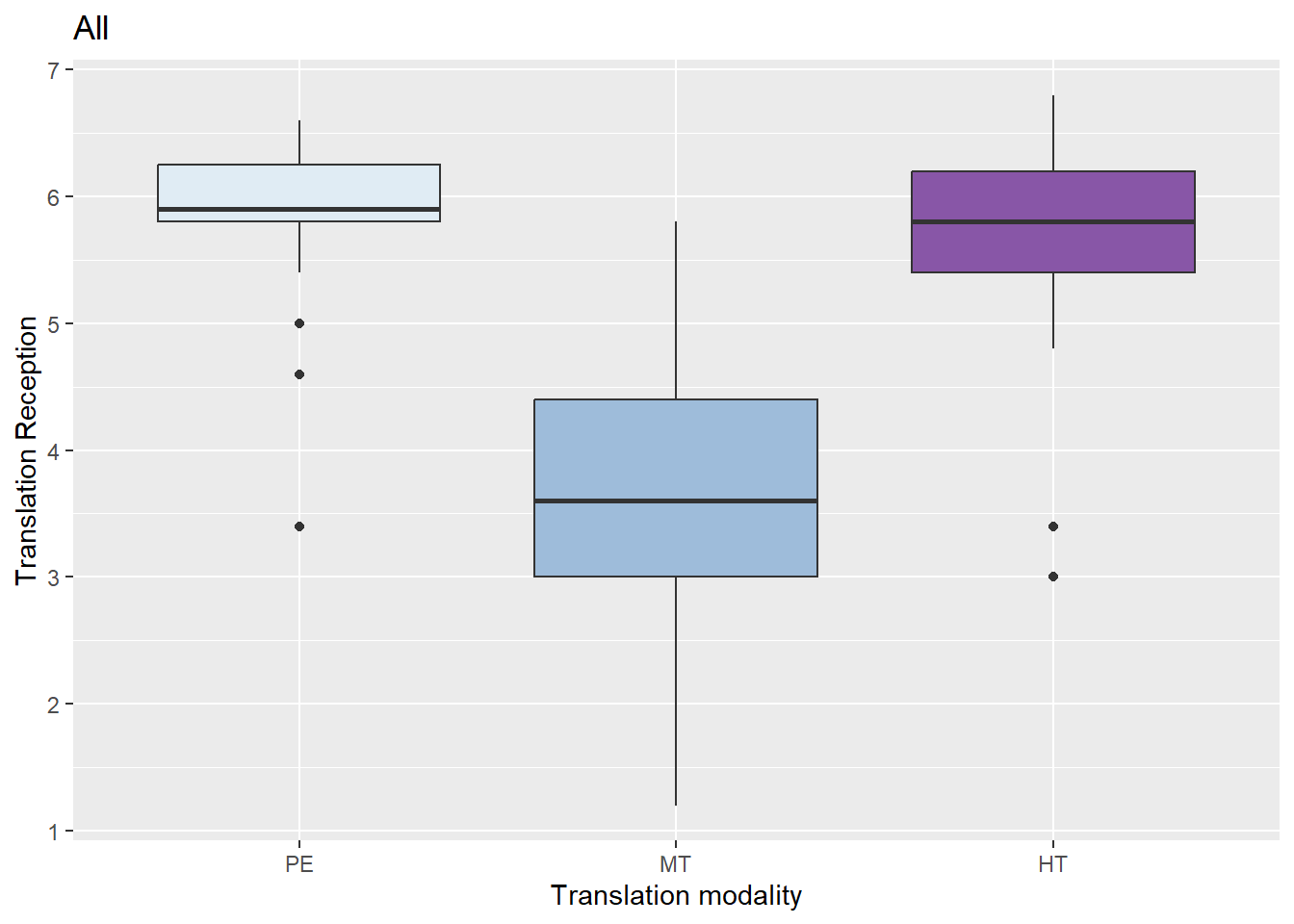

4.3.6 Translation reception

Figure 3 shows the results of the average scores given for this 5-item scale (α = 0.85) for translation reception (N = 119).

Figure 3: Translation reception according to modality in the main experiment

Figure 3 shows that differences between the conditions are even more pronounced than in enjoyment and narrative engagement. It appears that viewers perceived issues in the MT output. As before, the variable Translation_reception was analysed according to the translation modality using the Kruskal-Wallis test and statistically significant differences were found between conditions (H(2) = 63.52, p < .00) with a mean rank score of 79.58 for PE, 74.74 for HT and 23.49 for MT. Post-hoc comparisons show statistically significant differences between PE and MT (Z =10.52; p = .00) and between MT and HT (Z = -9.67; p = .00). Also as before, a linear regression model was run to see the interaction between the dependent variable Translation_reception based and the independent variables Modality and Viewing_frequency. However, the assumptions for homoscedasticity and normality17 are not met for the model, and therefore results are not presented.

Regarding the technical aspects of the subtitles, some participants commented on the subtitles being too fast. One PE viewer wrote that the “only negative for me was reading the subtitles quickly enough and feeling as if I was missing the expressions on the actors’ faces while I was busy reading”. A HT viewer also wrote that “I found that I missed the end of some sentences due to me looking at the characters”. Most participants who commented said that they enjoyed the programme and would like to see what happened next. One viewer of PE subtitles asked “W[h]ere can I watch the rest, Did they have a boy or girl??”, another wrote “I will probably find this now to continue watching properly as I was hooked!!”, and a viewer of HT said “[i]t was like a [S]panish version of [E]astenders”. The least favourable comments were from viewers who did not like soap operas, such as the PE viewer who wrote that the “acting was very cheesy and that is why I could not empathise with the characters - it was nothing to do with the language or use of subtitles”. Aside from complaints about speed, negative comments about subtitles came only from MT viewers (see Section 4.3.7). One wrote that the “subtitles drew me away from the scenes” and “made it more difficult to follow what was going on”.

Therefore, viewers who watch this subtitled telenovela in PE or HT conditions are significantly more positive about the translation than those who receive MT subtitles. We cannot confirm if the viewing frequency was a factor in translation reception.

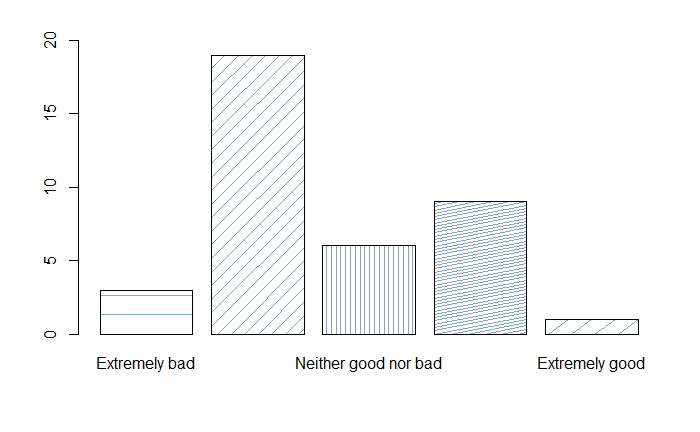

4.3.7 MT rating

When participants were debriefed about the nature of the experiment, those assigned to the MT (38) modality were asked if they were aware that the subtitles were machine translated, to rate the quality in a scale from 1 (Extremely bad) to 5 (Extremely good), and finally to choose their preferred translation modality from three options: Original Spanish, Translated by professionals, MT corrected by professionals. The reason why this group was asked about MT was because it was the only group exposed to this modality and we were interested in knowing the quality of the MT engine according to the viewers.

From the 38 participants, 6 said they had realised they were watching the telenovela with subtitles translated using MT, 15 “at times”, and 17 reported not knowing. This is interesting because although MT was rated the lowest in all categories, not all of them necessarily associated MT quality with their low rating. This is an indication that viewers might show a lower user experience when watching AVT content without necessarily knowing that this is partially due to using MT for subtitling. Figure 4 shows the values given by participants to the quality of the MT output.

Figure 4: Participants’ MT ratings

Figure 4 shows from left to right that 3 participants rated MT as Extremely bad; 19, the majority, rated MT as Slightly bad; followed by 6 as Neither good nor bad; then 9 as Slightly good, and 1 as Extremely good. The mean value for the quality of the MT output is 2.63.

Regarding preferences in translation, 24 participants prefer subtitles translated by professionals, 13 want MT corrected by professionals and one prefers the Original Spanish (this participant declared having a moderate knowledge of Spanish).

Participants who viewed MT used free comment space to highlight the problems with gender in MT (mentioned by 13 participants) or inconsistent translation of names (mentioned by 4 participants). Comprehension seemed to be difficult at times. One participant wrote that “there were words used that were not english at some point” [sic], and another found that a “whole scene was very hard to follow”. Yet another reported that “the subtitles did not relate to the conversation and did not make sense”.

5. Conclusions

The use of MT in subtitling workflows has become common practice to reduce costs and turnaround time (Georgakopoulou 2021). Our study, by borrowing methodology from previous reception studies in literary texts using MT in the translation process (Guerberof-Arenas and Toral 2020 and 2022), aims to see if AVT reception changes depending on the translation modality.

Our results show that viewers show higher engagement with PE than HT, but there is only a significant difference when PE is compared to MT. The categories where the difference is significant are Narrative Understanding and Narrative Presence. This is interesting because it shows that MT prevents viewers from understanding the story line and from being present in the story. When it comes to enjoyment, the differences are more pronounced, and viewers enjoy MT significantly less than PE and HT. Finally, in translation reception, the gap is even more pronounced between MT vs. PE and HT. In brief, measures showed that post-edited subtitles were just as well received (and scored higher values) and understood as unaided human translation with MT scoring significantly lower in all the scales measured.

These results might suggest that, for this genre and language pair at least, semi-automated translation using PE is a viable option for subtitling, as shown in previous literature (Bywood, Georgakopoulou, and Etchegoyhen 2017; Koponen et al. 2020b; Matusov, Wilken, and Georgakopoulou 2019). However, and this to us is critically important, the surprising finding is that the HTER scores in Section 3.3 demonstrate that a substantial amount of edits are necessary to render the automatic subtitles publishable, and this is the case in a genre (a telenovela) that has, in theory, an uncomplicated style. In our case, translators were not constrained by time nor by the rate paid (they were paid the rate quoted beforehand), so they could indeed edit the subtitles until they were happy with them to achieve publishable quality and this, in turn, resulted in an improved viewer experience. In combination, this suggests that high-quality PE for creative subtitling should be paid at full rate rather than reduced rates, or at the very least that the assumption that PE should entail reduced rates is not well supported by our findings. Time to translate and post-edit was not measured in our experiment, and time savings are an important factor when deciding on price.

We wonder if results would be comparable to those in this study were subtitlers not given sufficient time or acceptable remuneration for the post-editing task. It is important, therefore, that companies that use subtitling with MT in the workflow are transparent, and also that they allow researchers to carry out similar experiments to the one presented here in an open-data setting. Add to this the recommendation from, for example, Cadwell, O’Brien and Teixeira (2018) that implementation of partial automation of translation should be participatory rather than unilateral, and we can see how misgivings from translators and translator associations about the role of MT in contemporary subtitling workflows might be rooted in the considerable amount of work that MT requires so that it can be published.

There are many lessons from this iterative series of experiments that can be of value to other researchers or companies when assessing AVT reception. Translators used contemporary tools and the translation and PE tasks were mixed, which removed the confounding translator style effect and partially replicates the industry practice of splitting programmes into sections to reassemble post-hoc (Moorkens 2020). Care was taken so that participants were demographically similar, with a comparable interest in subtitled programming and level of proficiency in the source language. Experiment conditions were randomised and recruitment was via an independent platform, as snowball recruitment by researchers may attract participants with better knowledge of language and who are more exposed to subtitled media than other users.

While the methodology and results may be valuable, there are limitations to this study. Findings are limited to the ES-MX to EN-UK language pair and the genre of drama or soap opera. It would be valuable to measure translators’ effort in different modalities, ideally using a selection of language pairs and AV genres. Finally, due to time and financial constraints, the final subtitles are not evaluated to assess their quality or their level of creativity, and this can be a determining factor when looking at user experience.

Funding information

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 890697, and also the financial support of Science Foundation Ireland under Grant Agreement No. 13/RC/2106_P2 at the ADAPT SFI Research Centre at Dublin City University.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank AppTek and Yota Georgakopoulou for providing us with subtitled media. We would also like to thank the subtitlers and the viewers for their contribution to this study.

References

- ATAA, Association des Traducteurs/Adaptateurs de l'Audiovisuel (2021). Les mirages de la post-édition.

- https://www.ataa.fr/blog/article/les-mirages-de-la-post-edition

- ATRAE, Asociación de Traducción y Adaptación Audiovisual (2021). Comunicado sobre la posedición. https://atrae.org/comunicado-sobre-la-posedicion/

- AVTE AudioVisual Translators Europe (2022). AVTE Machine Translation Manifesto. AVTE. https://avteurope.eu/avte-machine-translation-manifesto/

- Busselle, Rick and Helena Bilandzic (2009). “Measuring Narrative Engagement.” Media Psychology 12 (4): 321–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213260903287259.

- Bywood, Lindsay, Panayota Georgakopoulou and Thierry Etchegoyhen (2017). “Embracing the Threat: Machine Translation as a Solution for Subtitling.” Perspectives 25 (3): 492–508. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2017.1291695.

- Cadwell, Patrick, Sharon O’Brien and Carlos S. C. Teixeira (2018). “Resistance and Accommodation: Factors for the (Non-) Adoption of Machine Translation among Professional Translators.” Perspectives 26 (3): 301–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2017.1337210.

- Cataño, Sergio and Nelhiño Acosta (2020). Te doy la vida [TV series]. Televisa.

- Dixon, Peter, Marisa Bortolussi, Leslie C. Twilley, and Alice Leung (1993). “Literary Processing and Interpretation: Towards Empirical Foundations.” Poetics 22 (1): 5–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-422X(93)90018-C.

- ELIS (2022). “ELIS 2022 – Follow Up Spring 2022” https://elis-survey.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/ELIS-2022-Followup-results.pdf

- García-Escribano, Alejandro Bolaños, Jorge Díaz-Cintas and Serenella Massidda (2021). “Subtitlers on the Cloud: The Use of Professional Web-Based Systems in Subtitling Practice and Training.” Tradumàtica: Tecnologies de La Traducció, no. 19 (December): 1–21. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/tradumatica.276.

- Georgakopoulou, Yota (2021). “Implementing Machine Translation in Subtitling | MultiLingual.” Multilingual Magazine, November 3, 2021. https://multilingual.com/implementing-machine-translation-in-subtitling/.

- Groskop, Viv (2021). “Lost in Translation? The One-Inch Truth about Netflix’s Subtitle Problem.” The Guardian, October 14, 2021, sec. Television & radio. https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2021/oct/14/squid-game-netflix-translations-subtitle-problem.

- Guerberof-Arenas, Ana and Antonio Toral (2020). “The impact of post-editing and machine translation on creativity and reading experience.” Translation Spaces 9 (2): 255–282. https://doi.org/10.1075/ts.20035.gue.

- Guerberof-Arenas, Ana and Antonio Toral (2022). “Creativity in Translation: Machine Translation as a Constraint for Literary Texts.” Translation Spaces 11 (2): 184–212. https://doi.org/10.1075/ts.21025.gue.

- Hakemulder, Jemeljan F (2004). “Foregrounding and Its Effect on Readers’ Perception.” Discourse Processes 38 (2): 193–218. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326950dp3802_3.

- Hassan, Hany, Anthony Aue, Chang Chen, Vishal Chowdhary, Jonathan Clark, Christian Federmann, Xuedong Huang, Marcin Junczys-Dowmunt, William Lewis, Mu Li, Shujie Liu, Tie-Yan Liu, Renqian Luo, Arul Menezes, Tao Qin, Frank Seide, Xu Tan, Fei Tian, Lijun Wu, Shuangzhi Wu, Yingce Xia, Dongdong Zhang, Zhirui Zhang and Ming Zhou (2018). “Achieving Human Parity on Automatic Chinese to English News Translation.” ArXiv:1803.05567 [Cs], June. http://arxiv.org/abs/1803.05567.

- Hu, Ke, Sharon O’Brien and Dorothy Kenny (2020). “A Reception Study of Machine Translated Subtitles for MOOCs.” Perspectives 28 (4): 521–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2019.1595069

- Iyuno SDI Group (2022). “A Simplified Look at the Subtitling Production Process.” https://iyuno.com/news/white-papers/a-simplified-look-at-the-subtitling-production-process.

- Karakanta, Alina, Luisa Bentivogli, Mauro Cettolo and Marco Turchi (2022). “Post-Editing in Automatic Subtitling: A Subtitlers’ Perspective.” Proceedings of the 23rd Annual Conference of the European Association for Machine Translation, 259–68. Ghent: EAMT. https://aclanthology.org/2022.eamt-1.29/

- Koponen, Maarit, Umut Sulubacak, Kaisa Vitikainen and Jörg Tiedemann (2020a). “MT for Subtitling: User Evaluation of Post-Editing Productivity.” Proceedings of the 22nd Annual Conference of the European Association for Machine Translation, 115–24. Lisboa, Portugal: European Association for Machine Translation. https://www.aclweb.org/anthology/2020.eamt-1.13.

- Lange, Jeva. 2021. “Squid Game and Netflix’s Subtitle Problem.” The Week, May 10, (2021). https://theweek.com/culture/1005620/squid-game-and-netflixs-subtitle-problem.

- Matusov, Evgeny, Patrick Wilken and Yota Georgakopoulou (2019). “Customizing Neural Machine Translation for Subtitling.” Proceedings of the Fourth Conference on Machine Translation (Volume 1: Research Papers), 82–93. Florence, Italy: Association for Computational Linguistics. https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/W19-5209.

- Mehta, Sneha, Bahareh Azarnoush, Boris Chen, Avneesh Saluja, Vinith Misra, Ballav Bihani and Ritwik Kumar (2020). “Simplify-Then-Translate: Automatic Preprocessing for Black-Box Machine Translation.” ArXiv:2005.11197 [Cs], May. http://arxiv.org/abs/2005.11197.

- Moorkens, Joss (2020). “‘A Tiny Cog in a Large Machine’: Digital Taylorism in the Translation Industry.” Translation Spaces 9 (1): 12–34. https://doi.org/10.1075/ts.00019.moo.

- Orrego-Carmona, David (2018). “Audiovisual Translation and Audience Reception.” Luis Pérez González (ed.) (2018). The Routledge Handbook of Audiovisual Translation. Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon; New York, NY: Routledge, 367–82.

- Ortiz Boix, Carla (2016). Implementing Machine Translation and Post-Editing to the Translation of Wildlife Documentaries through Voice-over and Off-Screen Dubbing. PhD Thesis. TDX (Tesis Doctorals En Xarxa), Barcelona: Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. http://www.tdx.cat/handle/10803/400020.

- Oziemblewska, Magdalena and Agnieszka Szarkowska (2022). “The Quality of Templates in Subtitling. A Survey on Current Market Practices and Changing Subtitler Competences.” Perspectives 30 (3): 432–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2020.1791919.

- Parra Escartín, Carla and Manuel Arcedillo (2015). “A Fuzzier Approach to Machine Translation Evaluation: A Pilot Study on Post-Editing Productivity and Automated Metrics in Commercial Settings.” Proceedings of the Fourth Workshop on Hybrid Approaches to Translation (HyTra), 40–45. Beijing: Association for Computational Linguistics. https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/W15-4107.

- Perego, Elisa, Fabio Del Missier, Marco Porta and Mauro Mosconi (2010). “The Cognitive Effectiveness of Subtitle Processing.” Media Psychology 13 (January): 243–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2010.502873.

- Popel, Martin, Marketa Tomkova, Jakub Tomek, Łukasz Kaiser, Jakob Uszkoreit, Ondřej Bojar and Zdeněk Žabokrtský (2020). “Transforming Machine Translation: A Deep Learning System Reaches News Translation Quality Comparable to Human Professionals.” Nature Communications 11 (1): 4381. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-18073-9.

- Rajendran, Dhevi J., Andrew T. Duchowski, Pilar Orero, Juan Martínez and Pablo Romero-Fresco (2013). “Effects of Text Chunking on Subtitling: A Quantitative and Qualitative Examination.” Perspectives 21 (1): 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2012.722651.

- Santilli, Damián (2021). Testing AppTek’s AVT specialized MT vs. Google’s general MT when subtitling a Mexican soap opera into English. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/testing-appteks-avt-specialized-mt-vs-googles-general-dami%C3%A1n-santilli/

- Schmidtke, Dag and Declan Groves (2019). “Automatic Translation for Software with Safe Velocity.” Proceedings of Machine Translation Summit XVII Volume 2: Translator, Project and User Tracks, 159–66. Dublin: European Association for Machine Translation. https://www.aclweb.org/anthology/W19-6729.

- Snover, Matthew, Bonnie Dorr, Richard Schwartz, Linnea Micciulla and John Makhoul (2006). “A Study of Translation Edit Rate with Targeted Human Annotation.” Proceedings of Association for Machine Translation in the Americas 200: 223–31.

- Szarkowska, Agnieszka, Izabela Krejtz and Krzysztof Krejtz (2017). “4. Do Shot Changes Really Induce the Rereading of Subtitles?” Jorge Díaz Cintas and Kristijan Nikoli (eds) (2017). Fast-Forwarding with Audiovisual Translation. Bristol, Blue Ridge Summit: Multilingual Matters, 61–79. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781783099375-007.

- Vieira, Lucas Nunes (2020). “Machine Translation in the News: A Framing Analysis of the Written Press.” Translation Spaces 9 (1): 98–122. https://doi.org/10.1075/ts.00023.nun.

- Ydewalle, Géry d’, Patrick Muylle and Johan van Rensbergen (1985). “Attention Shifts in Partially Redundant Information Situations.” Rudolf Groner, George McConkie, and Christine Menz (eds.) (1985). Eye Movements and Human Information Processing. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science, 375–384.

- Ydewalle, Géry d’, Johan Van Rensbergen, and Joris Pollet (1987). “Reading a Message When the Same Message Is Available Auditorily in Another Language: The Case of Subtitling.” John Kevin O’Regan and Ariane Levy-Schoen (eds) (1987). Eye Movements from Physiology to Cognition. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 313–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-70113-8.50047-3.

Biographies

Ana

Guerberof-Arenas is an Associate Professor at University of

Groningen. She was a Marie Skłodowska Curie Research Fellow at the

Computational Linguistics group with her CREAMT project that looked at

the impact of MT on translation creativity and the reader’s experience

in the context of literary texts. More recently she has been awarded an

ERC Consolidator grant to work on the five-year project INCREC that

explores the translation creative process in its intersection with

technology in literary and AV translations.

Ana

Guerberof-Arenas is an Associate Professor at University of

Groningen. She was a Marie Skłodowska Curie Research Fellow at the

Computational Linguistics group with her CREAMT project that looked at

the impact of MT on translation creativity and the reader’s experience

in the context of literary texts. More recently she has been awarded an

ERC Consolidator grant to work on the five-year project INCREC that

explores the translation creative process in its intersection with

technology in literary and AV translations.

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9820-7074

Joss

Moorkens is an Associate Professor at the School of Applied

Language and Intercultural Studies in Dublin City University (DCU),

Challenge Lead at the ADAPT Centre, and member of DCU's Institute of

Ethics, and Centre for Translation and Textual Studies. He is General

Co-Editor of Translation Spaces with Dorothy Kenny and coauthor of the

textbooks Translation Tools and Technologies (Routledge 2023)

Translation Automation (Routledge 2024).

Joss

Moorkens is an Associate Professor at the School of Applied

Language and Intercultural Studies in Dublin City University (DCU),

Challenge Lead at the ADAPT Centre, and member of DCU's Institute of

Ethics, and Centre for Translation and Textual Studies. He is General

Co-Editor of Translation Spaces with Dorothy Kenny and coauthor of the

textbooks Translation Tools and Technologies (Routledge 2023)

Translation Automation (Routledge 2024).

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0766-0071

David

Orrego-Carmona is an Associate Professor at the University of

Warwick and a Research Associate at the University of the Free State

(South Africa). David’s research deals primarily with translation,

technologies and users. Using qualitative and quantitative research

methods, his work explores the societal affordances and implications of

translation and technologies. He is treasurer of ESIST, the European

Association for Studies in Screen Translation, associate editor of the

journal Translation Spaces and deputy editor of JoSTrans, the Journal of

Specialised Translation.

David

Orrego-Carmona is an Associate Professor at the University of

Warwick and a Research Associate at the University of the Free State

(South Africa). David’s research deals primarily with translation,

technologies and users. Using qualitative and quantitative research

methods, his work explores the societal affordances and implications of

translation and technologies. He is treasurer of ESIST, the European

Association for Studies in Screen Translation, associate editor of the

journal Translation Spaces and deputy editor of JoSTrans, the Journal of

Specialised Translation.

david.orrego-carmona@warwick.ac.uk

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6459-1813

Notes

- Multidirectionality refers to the fact that the translation direction is not only from one language into another, for example, from English to Spanish and French, but from and into multiple languages.↩︎

- AppTek is a company that provides technology to transcribe, translate, understand and synthesise speech from text data: https://www.apptek.com/. The MT system was built by their Lead Science Architect and MT produced in March of 2021.↩︎

- The translation and post-editing was from Spanish into English, so the location of the participants did not affect the results.↩︎

- Appendix A is available in https://github.com/AnaGuerberof/CREAMTAVT.↩︎

We use MT as the reference translation and PE as the hypothesis when running HTER.↩︎

- The files and logs for HTER are in https://github.com/AnaGuerberof/CREAMTAVT/tree/main/TER↩︎

- By comparison, the HTER score for the HT condition was 62.26 - more distant from the MT, as we would expect. Results for literary PE from Guerberof-Arenas and Toral (2022) are similar for EN-NL, with even higher edit rates demonstrated for EN-CA.↩︎

- Unfortunately, we did not receive feedback from the other subtitler.↩︎

- The full questionnaire can be found here: https://github.com/AnaGuerberof/CREAMTAVT/upload/main/QualtricsQuestionnaire↩︎

- The anonymised data and the statistical analysis can be found here https://github.com/AnaGuerberof/CREAMTAVT/tree/main/Pilot↩︎

- This test is used to determine if there are statistically significant differences between two or more groups within the independent variable (condition) when the scale uses rank-based nonparametric values.↩︎

- The anonymised data and the statistical analysis can be found here https://github.com/AnaGuerberof/CREAMTAVT/tree/main/Prolific%201st↩︎

- The p values presented here are not adjusted. In the Conover-Iman test, the null hypothesis is rejected if p <= alpha/2.↩︎

- The anonymised data and the statistical analysis can be found here https://github.com/AnaGuerberof/CREAMTAVT/tree/main/Prolific%202nd↩︎

- Cronbach’s alpha measures the internal consistency of a scale. It gives an idea of how the items are interrelated and measure similar concepts.↩︎

- Linear regression models are used to describe the relationship between variables by running the line of best fit in the data and searching for the value of the regression coefficient (R) that minimises the total error of the model. They are especially suited to observe the interaction of several variables. These models need to meet certain assumptions that are calculated after running the model.↩︎

- Homoscedasticity is an assumption of equal variances in the groups being measured. This means in this case that the variance is not equal between groups and thus the results are not reliable. The normality assumption indicates that the data fits a bell curve. This means that our data does not fit the bell-shaped curve and thus the results of the model would be skewed and unreliable.↩︎