Linguistic Variations between Translated and Non-Translated Sports News: A Quantitative Linguistic Approach

Xinlei Jiang 1, School of Foreign Studies, Xi’an Jiaotong University

ABSTRACT

This study quantifies the linguistic variations between translated and non-translated sports news by using thirteen lexical and syntactic indices from quantitative linguistics and corpus linguistics, with the additional aim of testing the translation universals hypothesis. Through a 40,000-word comparable corpus, Random Forest analysis and statistical tests, this study identifies key linguistic indices that distinguish these two text types. The results reveal that 1) Writer’s View, Activity, R1, RRmc and ATL are the most significant predictors 2) translated texts exhibit significantly lower lexical density and diversity, reflected by lower R1 and RRmc values, but include significantly longer words (longer ATL), which supports the simplification hypothesis partially; 3) non-translated texts display higher Writer’s View and Activity scores, indicating greater authorial control over structural organisation and dynamic style compared with translators; and 4) the similar levels of MTLD, HL, Lambda, Entropy, MSL, MTL, MCL and Verb Distance observed in translated and non-translated texts align with the normalisation hypothesis. This study firstly presents a quantitative linguistic approach to examining the distinctive lexical and syntactic features of sports news translation. The findings support the simplification and normalisation hypotheses and reveal the self-organised and static styles of translated language, enriching the understanding of genre-specific translation universals.

KEYWORDS

Sports news translation, quantitative linguistics, translated and non-translated texts, translation universals, linguistic indices, Random Forest analysis

1. Introduction

As a product of the internationalisation of sports, sports translation plays a vital role in facilitating cross-cultural communication (Huo et al., 2024). The global passion for sports has fuelled the proliferation of professional sports outlets such as newspapers, traditional TV broadcasts and livestreaming, which serve as critical conduits not only for remote participation in sports but also for information dissemination on the one hand and for creating connections among people across the globe for the respective sport event. As an integral part of everyday life, sports news exhibits unique characteristics (e.g., timeliness and interest) and demands precise translation to convey concise and accurate information effectively to a broad audience (Zhang & Yang, 2024). As a mediator of global communication, news translation plays a key role in the transmission of information across cultural boundaries, a process that takes place every moment and has become increasingly significant with the advancement of communication technologies (Bielsa & Bassnett, 2008). Situated at the intersection of sports and news translation, sports news translation involves rendering reports on sports and major sporting events across languages and cultures, and has gained increasing prominence amidst the growing demand for cross-cultural communication (Chen, 2011; Khedri & Fumani, 2016). To our knowledge, despite the wealth of qualitative research (Huo et al., 2024; Sâsâiac & Brunello, 2014; Wilcock, 2020; Zhang & Yang, 2024), there remains a notable gap in quantitative investigations into the linguistic features of sports news translation. Additionally, sports news translation has been underexplored in its potential to verify the existence of translation universals – one of the core yet contentious issues in translation studies (see Chesterman 2008; Xiao 2010; Jia et al. 2022).

Based on comparable corpora of Chinese–into–English translated sports news and English non-translated sports news, this exploratory study seeks to identify the distinctive linguistic features of translated sports news in comparison to its non-translated counterparts. By using thirteen quantitative linguistic and corpus-based linguistic indices alongside Random Forest analysis and statistical tests, this research highlights the key features that differentiate translated texts from non-translated ones. Adopting a quantitative linguistic approach, the study provides a comprehensive characterisation of the linguistic features of sports news translation, shedding light on the nature of this specialised language variety. Furthermore, it offers novel insights into the translation universals debate through evidence from this relatively uncharted genre.

1.1 Sports news translation

In recent years, sports translation has emerged as a significant area of research, reflecting both the increasing globalisation of sports and the growing need for effective cross-cultural communication. This field includes diverse topics, such as the translation of idiomatic expressions and metaphors (Al Kayed, 2023; Emrah, 2022; Khalaf, 2022), translation strategies and practices (Anyawuike, 2023; Boynukara, 2017; Itaya, 2021; Milić, 2014; Sandrelli, 2015), global and cultural contexts (Baines, 2013; Holtzhausen et al., 2021; Jackson et al., 2005; Luo, 2013; Monaco et al., 2022) and competences and expertise (Gafiyatova & Pomortseva, 2016; Ghignoli et al., 2015). Sports news translation involves not only the interlingual transfer of meaning but also the transposition of information in a textual format aimed at meeting the demands of target readership (Bielsa & Bassnett, 2008). It is inherently shaped by cross-cultural variables (Liu, 2017), including linguistic variables (Chen, 2011; Li, 2024), narrative and framing variables (Wilcock, 2020) and pragmatic and stylistic variables (Bielsa & Bassnett, 2008; Zhang & Yang, 2024).

Chen (2011) highlighted that transediting, a special type of translation combining both the translating and editing processes, is required in news translation to balance accuracy with cultural acceptability. She pointed that although considerable editing work is involved in translated news texts, most existing studies on cross-linguistic news communication opt for term as news translation. Wilcock (2020) demonstrated how framing and reframing strategies are employed in sports news translation to meet target audience expectations, involving selective appropriation and rhetorical adjustments for enhanced cultural relevance. Xu (2024) employed communicative translation theory to balance factual accuracy with emotional engagement, effectively capturing the atmosphere of sports events, while Mao (2024) applied functional equivalence theory to achieve cultural and emotional fidelity in sports translation. Zhang and Yang (2024) analysed linguistic features unique to sports reporting, such as vocabulary, sentence structures and rhetorical devices, advocating for translation strategies that preserve these elements to convey the source text’s tone and style effectively. Based on Chinese–into–English (L1–L2) news translation by Xinhua News Agency (China’s state media), Li (2024) observed stylistic adjustments aimed at enhancing both credibility and image building, while Liu (2017) highlighted the shift of Chinese news translation from a traditional translational approach to a more multidisciplinary stage. These pioneering studies underscore the hybridity and cultural specificity of sports news translation, which demands linguistic precision, cultural sensitivity and adaptability for diverse audiences.

However, despite a rich foundation of qualitative research on sports translation (Huo et al., 2024; Sâsâiac & Brunello, 2014; Wilcock, 2020; Zhang & Yang, 2024), and limited quantitative studies on sports news (Callies & Levin, 2019; Fest, 2016), quantitative investigations into the linguistic features of sports news translation – such as lexical and syntactic complexity in comparison with non-translated counterparts – are notably lacking. A systematic exploration of quantifiable features could provide empirical evidence of the distinct characteristics of this specialised language variety, offering insights into how translation shapes news discourse and facilitates the global dissemination of sports culture.

1.2 Translation universals

Translated language is often considered a distinct "third code" (Frawley, 1984), a "hybrid language" (Schäffner & Adab, 2001; Trosborg, 1997) or a "language of a special kind" (differing from both the original source language and the non-translated target language) (Mauranen, 1999). For decades, exploring universal features or general patterns of translated language has been a focal issue in corpus-based translation studies. A pivotal contribution to this effort was Baker’s (1993) introduction of the term “translation universals,” which posits that translations exhibit inherent linguistic characteristics caused in and by the process of translation. Extending this notion, McEnery and Xiao (2007, p.8) referred to translated language as “at best an unrepresentative special variant of the target language.” To refine the scope of inquiry, Chesterman (2004, p.7) distinguished between “S-universals,” related to source-text processing and requiring parallel corpora of source and target texts, and “T-universals,” which focus on target-language processing and rely on comparable corpora of translated and non-translated texts.

Among the most extensively studied T-universals are simplification and normalisation (Baker, 1996). These are investigated across linguistic levels, genres and language pairs. However, empirical findings remain inconclusive, with both supporting and conflicting evidence reported in the literature.

Simplification refers to “the tendency to simplify the language used in translation” (Baker, 1996, pp. 181–182), suggesting that translated language tends to be simpler at lexical, syntactic and/or stylistic levels than native language (cf. Blum-Kulka & Levenston, 1983; Laviosa-Braithwaite, 1997). Researchers operationalise this concept by measuring features believed to indicate reduced complexity, such as lexical density, type-token ratio (TTR) and sentence length. Comparing translated and non-translated newspapers and narratives, Laviosa (1998a, 1998b) observed that translated texts exhibited higher lexical simplification, as evidenced by lower lexical density and TTR. However, using the same measures, Williams (2005) failed to confirm the simplification hypothesis in French translated government texts. Similarly, conflicting findings have been reported for mean sentence length in translated newspapers (Laviosa,1998a) and in translated narrative texts (Laviosa, 1998b). In English–Chinese fiction translation, Xiao and Yue (2009) discovered that translated Chinese fiction displayed significantly lower lexical density, significantly greater mean sentence length and non-significantly lower standardised type–token ratio (STTR) compared with non-translated fiction. Based on balanced comparable corpora, Xiao (2010) found significantly lower lexical density, non-significantly comparable STTR, higher proportion of high-frequency words over low-frequency words and higher repetition rate of high-frequency words in translated Chinese, partially supporting the simplification hypothesis. However, Xiao (2010) also noted that mean sentence length varied significantly with genre, suggesting that simplification may be a genre- or language-pair-specific phenomenon rather than a universal trait. Cvrček and Chlumská (2015) further corroborated simplification in Czech translations, identifying lower TTR in translated literary texts compared with their non-translated counterparts. Using list head coverage, lexical density and the proportion of high-frequency words, Kajzer-Wietrzny (2015) compared English simultaneous interpretation and translation from German, Dutch, French and Spanish with original English speeches. The interpreted texts displayed only simplification measured by list head coverage, while translated texts show no significant differences across three measures. Liu and Afzaal (2021) analysed thirteen syntactic complexity measures (i.e. length of production unit, amount of subordination, amount of coordination, phrasal complexity and overall sentence complexity) across four genres, confirming that genre influences the complexity of translated texts. Specifically, translated news resembled native news, while translated general prose and academic writing were less complex than their native counterparts, and translated fiction was more complex than non-translated fiction. Liu et al. (2022) demonstrated that translated Chinese tended to exhibit lexical simplification, as indicated by unigram entropy, though not at the syntactic level based on part-of-speech (POS) entropy. Expanding on this, Liu et al. (2023) used fourteen syntactic complexity measures from of Second Language Syntactic Complexity Analyzer (L2SCA; Lu, 2010) and found that interpreted speeches scored significantly lower on most measures compared with non-interpreted speeches.

Like simplification, normalisation remains a contentious hypothesis in translation studies. Normalisation, or conventionalisation (Mauranen, 2007), refers to the “tendency to conform to patterns and practices typical of the target language, even to the point of exaggerating them” (Baker, 1996, p.183). Similarly, Toury (1995, p.268) introduced the concept of standardisation, “a tendency whereby translated choices tend to conform to the more frequent and conventional uses in non-translated language rather than using other options available”. Empirical studies often assess normalisation by examining conformity to target language frequencies and distributions, such as STTR, part-of-speech (POS) patterns, and usage of high-frequency words. Kenny’s (2000a, 2000b, 2001) series of studies on lexical normalisation in German–English literary texts revealed a coexistence of normalising and non-normalising shifts, indicating that normalisation may vary across cultures and genres. Xia (2014) expanded this inquiry to English–Chinese translations, finding competing tendencies of normalisation (i.e., conformance to certain textual norms) and denormalisation (i.e., alienating from the norms) at both lexical and syntactic levels. denormalisation. Delaere et al. (2012) measured linguistic distances in Belgian Dutch translations across six text types (fiction, non-fiction, journalistic, administrative texts, external communication) and confirmed general trends of standardisation, though genre significantly influenced these differences. Wu and Li (2021) analysed normalising tendencies in four translations of Louis Cha’s martial arts fiction using BNC Baby (fiction) as a reference. While overall findings supported lexical normalisation, individual translations showed varying degrees of conformity. One translation, by Minford, exhibited the highest degree of normalisation, closely resembling non-translated texts in terms of STTR, part of POS distribution and high-frequency word usage.

Given the aforementioned mixed evidence for or against simplification and normalisation hypotheses, scholars (e.g., Rabadán & Gutiérrez-Lanza, 2023) have re-evaluated the universals claims in translation. They argue that such features may vary significantly across genres and language pairs. Moreover, some researchers question whether these patterns are genuinely universal or are better explained by genre-specific conventions, language-pair characteristics or translation norms (Toury, 1995; House, 2008; Pym, 2008). This highlights the need for further investigation into the distinctive features of translated language, particularly in genetically distant language pairs such as Chinese–English (Xiao, 2010) and in underexplored genres like sports news.

1.3 Quantitative linguistic approach

Quantitative Linguistics (QL), a sub-discipline of linguistics, investigates various language phenomena, language structures, structural properties and their interrelations in real-life communication (Köhler et al., 2005; Liu, 2017). By examining the structural properties of natural language texts, QL aims to model the dynamic systems of languages and their development based on authentic linguistic data (Altmann, 1978; Chen & Xu, 2019; Köhler, 2012; Liu et al., 2009; Zipf, 1935). With the advent of the corpus- and data-driven revolution (Boulton & Cobb, 2017; Godwin-Jones, 2017; Jiang et al., 2019), linguistics has experienced a remarkable quantitative shift over the past two decades (Kortmann, 2021; Lei & Liu, 2019).

By means of diverse quantitative techniques, QL uses precise measurement, observation, simulation, modelling and explanation to uncover the governing principles and intrinsic driving forces behind language phenomena (Chen & Liu, 2014). QL has experienced significant development, particularly through systematic exploration across various linguistic areas and levels (Těšitelová, 1992). Its applications now extend to diverse research domains, including genre analysis, interlanguage studies, language typology, translation, interpretation, diachronic linguistics, psycholinguistics, authorship attribution, discriminant analysis, natural language processing, as well as interdisciplinary fields such as music, genomics and animal communication (e.g., Chen & Liu, 2014; Chen & Xu, 2019; Du, 2023; Liu, 2017; Melka & Místecký, 2020; Tuzzi et al., 2015; Xiao & Sun, 2020; Jiang et al., 2022; 2024)

A notable strength of QL lies in its arsenal of linguistic indices, which serve as proxies for various structural, stylistic and cognitive properties of texts (Popescu et al., 2009). These indices are theoretically motivated and designed to capture dynamic variation within and across genres, languages and modes of production (e.g., Chen & Liu, 2014; Tuzzi et al., 2015). For example, R1 (an indicator of vocabulary richness based on the h-point), Hapax Legomena Percentage (HL), Repeat Rate (RR) and Relative Repeat Rate (RRmc) capture lexical richness, diversity and sophistication; Entropy, R4 (the reversed Gini coefficient), Thematic Concentration and Gini Coefficient measure information distribution and concentration; Lambda, Adjusted Modulus and Arc Length portray the frequency structure; H-point, Writers’ View, Activity, Descriptivity and Verb Distance reveal the stylistic preferences, genre variation and social-psychological features (Liu, 2017; Kubát et al., 2014).

In prior literature, Pan et al. (2015) analysed the aesthetic properties of Chinese contemporary poetry using H-point and Writer’s View. Chen and Xu (2019) used measures such as Zipfian parameters, H-point, Hapax Legomena Percentage, Writer’s View and Curve Length to assess second language learners’ interlanguage proficiency, finding that H-point and Curve Length were effective in distinguishing language styles and task types, while Zipfian parameters differentiated language levels. Similarly, Xiao and Sun (2020) applied TTR, H-point, R1 and Writer’s View to capture the lexical features and their dynamic changes in PhD theses across disciplines, including the natural sciences, social sciences and humanities. To extract style-related features of the novelette, Melka and Místecký (2020) used a range of quantitative indices, including TTR, Entropy, RR, RRmc, Gini Coefficient, Average Token Length, HL, Moving-Average TTR, Lambda and Activity. Their analysis revealed the characteristic traits of the style and the underlying socio-psychological background. Jia and Liang (2020) applied the Activity to measuring lexical category bias across different interpreting types, namely simultaneous interpreting (SI), consecutive interpreting (CI) and read-out translated speech (TR). Their study found that CI outputs exhibited greater Activity than SI outputs, which they attributed to the lower frequency of adjectives in CI. This striking reduction in adjectives during CI processing, they argued, may result from the higher cognitive demands associated with CI compared with SI. These demands likely drive interpreters to minimise the use of adjectives as a strategy to manage cognitive load.

Further demonstrating the potential of QL, Jiang et al., (2022) used thirteen indices (i.e., TTR, H-point, Activity, Entropy, R1, Average Token Length, Lambda, Writer’s View, Verb Distances, Adjusted Modulus, HL, Gini Coefficient and RRmc) to quantify the drift of Queen’s English towards common people’s English, both lexically and syntactically. Xiao et al. (2023) conducted an entropy-based analysis to examine the distribution pattern of information content across moves and the variations in research article abstracts across disciplines. Du (2023) applied 11 indices (i.e., Adjusted Modulus, Average Token Length, Entropy, Gini Coefficient, HL, Lambda, R1, RRmc, Verb Distances and Writer’s View) to detect and predict psychological states in texts.

In summary, QL is a relatively young but rapidly evolving discipline with applications spanning diverse areas of linguistic research (Tuzzi et al., 2015). Yet, despite the demonstrated utility of quantitative indices in other linguistic branches, their application to translation studies, especially specialised translation, remains underexplored as well as little utilised. Amid the quantitative turn in linguistics, integrating QL provides a complementary methodological lens for identifying patterns of variation and regularity in translation. This approach facilitates the operationalisation of translation universals, particularly simplification and normalisation, across genres and languages.

1.4 Current study

Building on the existing literature, the following research gaps can be addressed. First, while qualitative analyses of sports news translation have shed light on its role, a comprehensive depiction of the quantifiable features of this specialised language variety is lacking. Second, amidst ongoing debate over the inherent versus genre-sensitive nature of translation universals, fresh evidence from sports news translation – an underexplored genre – is required. Third, despite its wide applicability across linguistic research, the potential of quantitative linguistic approaches in distinguishing sports news translation from non-translated counterparts remains underused.

To bridge these gaps, the present study focused on 9 quantitative linguistic indices (i.e., R1, Relative Repeat Rate, Hapax Legomena Percentage, Lambda, Entropy, Average Token Length, Writer’s View, Activity and Verb Distance) and 4 traditional corpus linguistic indices (e.g., Measure of Textual Lexical Diversity, Mean Sentence Length, Mean T-unit Length, Mean Clause Length) to capture linguistic variations between translated and non-translated sports news using DIY comparable corpora of written texts.

The research addressed the following questions:

Which of the thirteen linguistic indices, as identified through Random Forest analysis, most effectively differentiate translated and non-translated sports news?

Which of the thirteen linguistic indices show significant differences between translated and non-translated sports news, and how are these differences manifested?

For each key linguistic feature, how does it influence the model’s predictions in classifying translated versus non-translated texts?

2 Methodology

2.1 Corpus compilation

Our comparable corpus includes 60 non-translated and 60 translated sports news articles, totalling approximately 40,000 words. The non-translated texts consist of original English sports news retrieved from BBC News (BBC, n.d.), covering various sports events (e.g., tennis, basketball, soccer and Olympic events) from 2023 to 2024. The translated texts are English translations of Chinese sports news retrieved from the English version of Xinhua News Agency (n.d.), reporting on the same range of sports during the same period. Xinhua News Agency’s English output is drafted by professional Chinese translators based on Chinese source texts, and subsequently edited and polished by English native-speaker editors to meet international journalistic standards (Li, 2024). Although this collective process blends L2 translation with adaptation, its hybrid nature as a product of translating and editing is widely recognised as a defining feature of news translation rather than a methodological flaw (Frawley, 1984; Schäffner & Adab, 2001). In this study, both non-translated and translated texts are comparable in genre, time span and text size (see Table 1 for a corpus overview). Although subcorpora cover overlapping sports disciplines, including tennis, basketball, soccer and Olympic events, though not include identical coverage of specific contests.

| Subcorpora | Contents | Number of Texts | Word Count |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-translated sports news | BBC News (2023-2024) |

60 | 19672 |

| Translated sports news | Xinhua News Agency (2023-2024) |

60 | 20330 |

Table 1. Overview of the Corpus

2.2 Indices computation

Linguistic variations between non-translated and translated sports news were measured using seven lexical indices including Measure of Textual Lexical Diversity, R1, Relative Repeat Rate, Hepax Legomena Percentage, Lambda, Entropy and Average Token Length, and six syntactic indices including Writer’s View, Mean Sentence Length, Mean T-unit Length, Mean Clause Length, Activity and Verb Distance.

Lexical indices

As a traditional and widely-used measure of lexical diversity, TTR is claimed to be inherently flawed, as it is substantially sensitive to text length (Kubát et al., 2014; Melka & Místecký, 2019). To eliminate the potential effect of text length, this study applied MTLD to measuring lexical diversity. MTLD, the Measure of Textual Lexical Diversity (McCarthy, 2005), is based on the average number of tokens it takes to reach a given TTR value (e.g., 0.72). MTLD presents two strengths: it is robust with regard to text length variations, and it correlates highly with all the established lexical diversity indices such as Maas, Yule’s K, vocd-D and HD-D (McCarthy & Jarvis, 2010). MTLD scores were automatically computed using Coh-Metrix 3.0 (Graesser et al., 2004).

R1 is a measure of vocabulary richness, designed to estimate the proportion of content words in a text. It is based on the concept of the H-point, a boundary point on a word frequency list where a word’s frequency equals its rank Kubát et al., 2014). The H-point originates from scientometrics (Hirsch, 2005) and was introduced into text analysis by Popescu (2007). In a rank-frequency distribution of words (where words are ordered from most to least frequent), the H-point represents the position where frequency and rank intersect, capturing a balance between very frequent and less frequent words. Once the h-point is identified, R1 is calculated to estimate the proportion of content words beyond this boundary. Technically, R1 is calculated as:

$$R_{1} = 1 - \left( F(h) - \frac{h^{2}}{2N} \right) = 1 - \left( \frac{\sum_{r = 1}^{h}f_{i}}{N} - \frac{h^{2}}{2N} \right)$$

where F(h) is the cumulative frequency of words up to the H-point, and N is the total number of tokens in the text. Higher R1 values indicate a greater proportion of content words and, therefore, greater lexical richness.

Repeat Rate (RR) reflects the degree of vocabulary concentration. Yule’s (1944, 2014) “Characteristic K” indicates through inversion that the richer the text is, the smaller the repetition of words is. It is defined as:

$$RR = \sum_{r = 1}^{V}P_{i}^{2}$$

where Pi are the individual probabilities. If estimated by means of relative frequencies, Pi = fi/N, where fi are the absolute frequencies and N is number of tokens. Relative Repeat Rate (RRmc) was proposed by McIntosh (1967), yielding:

$${RR}_{mc} = \frac{1 - \sqrt{RR}}{1 - \frac{1}{\sqrt{V}}}$$

This amendment to the original formula puts RRmc in the interval <0;1>, making it comparable across different texts and languages. The higher RRmc indicates fewer repeated words, reflecting a lower concentration and greater lexical diversity a text has.

Hepax legomena are words that occur in a text only once (Popescu et al., 2009). Hepax Legomena Percentage (HL) is a ratio between the number of tokens (N) and number of hapax legomena (Nh) in a text, obtained as:

$$HL = \frac{N_{h}}{N}$$

Deriving from Arc length (L), Lambda (Λ) is a stable indicator of frequency structure (Popescu et al., 2009; Popescu et al., 2011). Describing the structure which emerges from language usage, Lambda mirrors a more synthetic form (with a higher value) or a more analytical form of the given language (with a lower value) (Popescu et al., 2011). L refers to the sum of Euclidean distances (Dr) between all neighboring frequencies:

$$L = \sum_{r = 1}^{V - 1}D_{r} = \sum_{r = 1}^{V - 1}\sqrt{{(f(r) - f(r + 1))}^{2} + 1}$$

Then Lambda is calculated as follows:

$$\Lambda = \frac{L\left( \log_{10}N \right)}{N}$$

Borrowed from information theory (Shannon, 1948), Entropy (H) measures the degree of vocabulary dispersion in a text and can also be interpreted as its monotony (Kubát et al., 2014; Liu, 2017; Melka & Místecký, 2019). The smaller the Entropy is, the more concentrated the vocabulary is and the less rich the vocabulary is. Entropy is computed via:

$$H = - \sum_{i = 1}^{K}{P_{i}\log_{2}P_{i}}$$

$$p_{i} = \frac{f_{i}}{N}$$

where K is the inventory size, pi the relative frequency of a given word, and fi the absolute frequency.

Calculating the arithmetic mean of the lengths of tokens, Average Token Length (ATL) is directly linked to complexity or style (Kubát et al., 2014; Liu, 2017).

$$ATL = \frac{1}{N}\sum_{i = 1}^{N}x_{i}$$

with x as individual word size/length.

Syntactic indices

Writer’s View (WV) reflects writers’ control over function words and content words in their writing process and aesthetic pursuit (Popescu & Altmann, 2007; Popescu et al., 2012). If we regard the last-ranked word with the lowest frequency as P1(V; 1), the first-ranked word with the highest frequency as P2(1; f (1)) and H-point as P3 based on the rank-frequency distribution curve, the angle α at the crossing of P3P1 with P3P2 can be termed as “writer’s view”, with its radian (arccosine value) converging to the golden ratio (~1.618.).

$$\cos\alpha = \frac{- \left\lbrack (h - 1)\left( f_{1} - h \right) + (h - 1)(V - h) \right\rbrack}{\left\lbrack {(h - 1)}^{2} + {(f_{1} - h)}^{2} \right\rbrack^{\frac{1}{2}}\left\lbrack {(h - 1)}^{2} + {(V - h)}^{2} \right\rbrack^{\frac{1}{2}}}$$

The greater control the writer takes, the further the WV is from the golden ratio; the more self-organised a text is, the more proximate the WV is to the golden ratio (Chen & Xu, 2019; Popescu et al., 2012).

Mean Sentence Length (MSL), Mean T-unit Length (MTL), Mean Clause Length (MCL) were generated using L2SCA (Lu, 2010). A sentence is a group of words delimited with one of the punctuation marks that signal the end of a sentence; a clause is defined as a structure with a subject and a finite verb; and a T-unit is one main clause plus any subordinate clause or nonclausal structure that is attached to or embedded in it (Lu, 2010, pp. 481–482).

Activity (Q) or active-descriptive (dis) equilibrium is measured in terms of Busemann’s coefficient (Busemann, 1925; Melka & Místecký, 2019; Zörnig et al., 2015), rendered as:

$$Q = \frac{V}{V + A}$$

with V and A denoting the number of verbs and adjectives respectively. Used in psychology and linguistics for text, style, characterisation of persons as well as historical analysis (Zörnig et al., 2015), activity expresses the interaction between active and descriptive “forces” (Popescu et al., 2014). If Q>0.5, the text can be regarded as “active”; if smaller than 0.5, it is regarded as “descriptive” (Zörnig et al., 2015). High Activity values may indicate a comprehensible language that avoids rich adjectival embellishments, and low values may indicate missing animation, related to the nominal (substantive-based) character of the texts (Melka & Místecký, 2019; Zörnig & Altmann, 2016).

Verb Distances (VD) count how many tokens on average there are between two successive verbs, computed as (Kubát et al., 2014):

$$VD = \frac{1}{N_{v} - 1}\sum_{i = 2}^{N_{v}}\left( V_{i} - V_{i - 1} - 1 \right)$$

with i as the order of the appearance of the verb among all the verbs in the text, Vi the linear position of the verb in the text, and NV the number of all the verbs.

VD has great potentials for characterising properties of languages, texts and style (Liu, 2017). Since the number and sequences of verbs can help disclose some aspects of the text dynamics (Zörnig et al., 2015), VD can both exhibit the syntactic features and detect the sequential text organisation in a quantitative context (Jiang et al., 2022).

All thirteen indices described above capture the lexical and syntactic features of translated and non-translated sports news. For nineteen quantitative linguistic indices, R1, RRmc, HL, Lambda, Entropy, ATL and Writer’s View were computed automatically using QUITA (Quantitative Index Text Analyzer) (Kubát et al., 2014). Activity and Verb Distance were calculated in MS Excel based on tagged texts processed with TagAnt 2.1.1 (Anthony, 2024). Descriptive statistics for the thirteen indices are presented in Table 2.

| Index | M | SD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-translated | Translated | Non-translated | Translated | |

| Lexical level | ||||

| MTLD: Measure of Textual Lexical Diversity | 118.607 | 110.466 | 28.348 | 28.299 |

| R1 | 0.861 | 0.846 | 0.029 | 0.032 |

| RRmc: Relative Repeat Rate | 0.957 | 0.950 | 0.009 | 0.011 |

| HL: Hepax Legomena Percentage | 0.418 | 0.412 | 0.071 | 0.071 |

| Λ: Lambda | 1.506 | 1.526 | 0.098 | 0.109 |

| H: Entropy | 6.938 | 6.899 | 0.343 | 0.403 |

| ATL: Average Token Length | 4.580 | 4.718 | 0.233 | 0.327 |

| Syntactic level | ||||

| WV: Writer’s View | 2.030 | 1.935 | 0.157 | 0.118 |

| MSL: Mean Sentence Length | 24.088 | 22.825 | 4.001 | 4.551 |

| MTL: Mean T-unit Length | 21.789 | 20.753 | 4.132 | 4.339 |

| MCL: Mean Clause Length | 13.289 | 13.922 | 3.176 | 3.240 |

| Q: Active-descriptive Equilibrium | 0.628 | 0.569 | 0.092 | 0.085 |

| VD: Verb Distance | 8.668 | 9.547 | 2.184 | 2.909 |

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of thirteen indices

2.3 Data analysis

We analysed linguistic variation between translated and non-translated sports news using a Random Forest classification model. The model was trained on a comparable corpus, where text type (translated or non-translated) served as the response variable and thirteen indices of linguistic features as predictors. An error plot was generated to assess the out-of-bag (OOB) error across a range of tree numbers, supporting model tuning by identifying the point of error convergence. Variable importance was assessed and visualised based on the Gini index, which revealed each index’s discriminatory power in distinguishing translated from non-translated texts. In addition, independent samples t-tests were conducted for each of the 13 indices to explore statistically significant differences between the two text types. We acknowledge that t-tests assume feature independence and do not account for interaction effects, which the Random Forest model inherently captures (Breiman, 2001). Thus, the t-test results are interpreted cautiously as complementary evidence of feature importance. Partial Dependence Plots (PDPs) were then generated for indices confirmed as significant through these t-tests. PDPs visualise the effect of individual features on the probability of classifying a text as non-translated, while controlling for the influence of all other features. PDPs analysis thus enhances our understanding of how these statistically significant features independently contribute to text classification in the Random Forest model. Given the relatively small corpus size and moderate number of features, the used of a Random Forest classier along with validation through OOB error estimation helps mitigate the risk of overfitting.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Model performance and variable importance

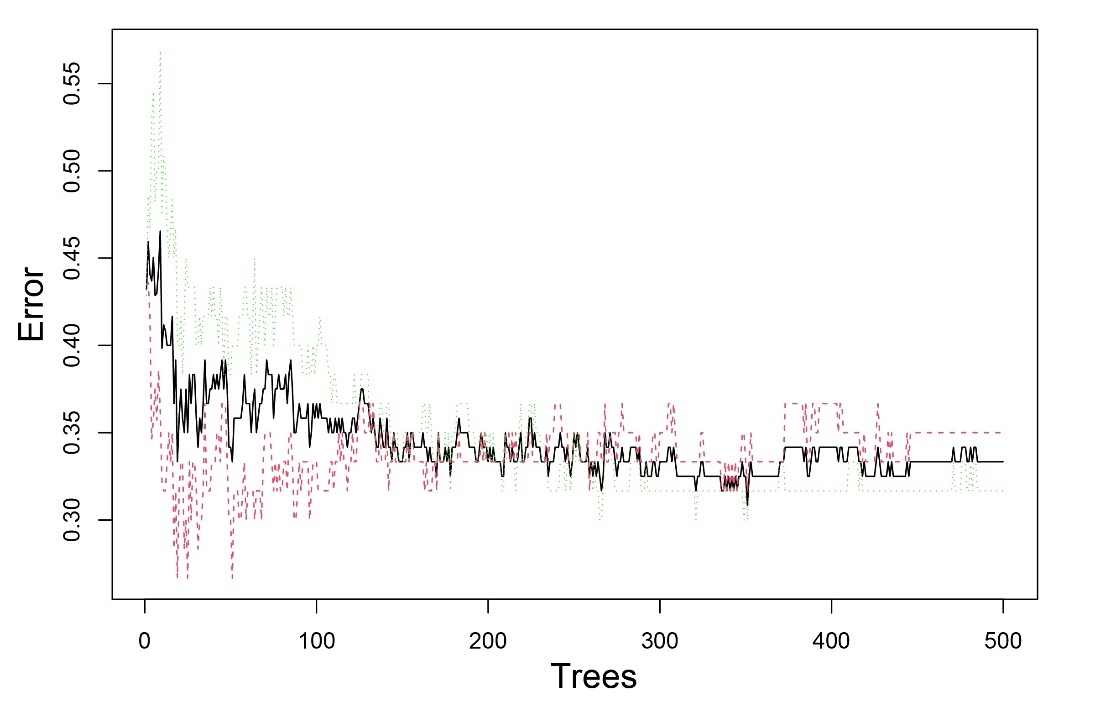

We used the ‘randomForest’ package in R to construct a Random Forest classification model. As shown in Figure 1, the performance of the Random Forest model stabilised after approximately 100 trees, with the out-of-bag (OOB) error converging around 0.3. This indicates that increasing the number of trees beyond this point did not substantially improve the model’s accuracy. The class-specific error rates for translated and non-translated texts respectively followed a similar pattern, suggesting that the model distinguishes both text types with comparable accuracy. Error-rate stabilisation demonstrates that the model achieves a good balance between complexity and interpretability, providing a robust foundation for analysing which linguistic features most strongly differentiate translated from non-translated sports news. This stability also suggests that the linguistic features included in the model capture systematic patterns of variation between the two text types, rather than reflecting random noise or overfitting to the dataset.

Figure 1. Error rate vs. number of trees

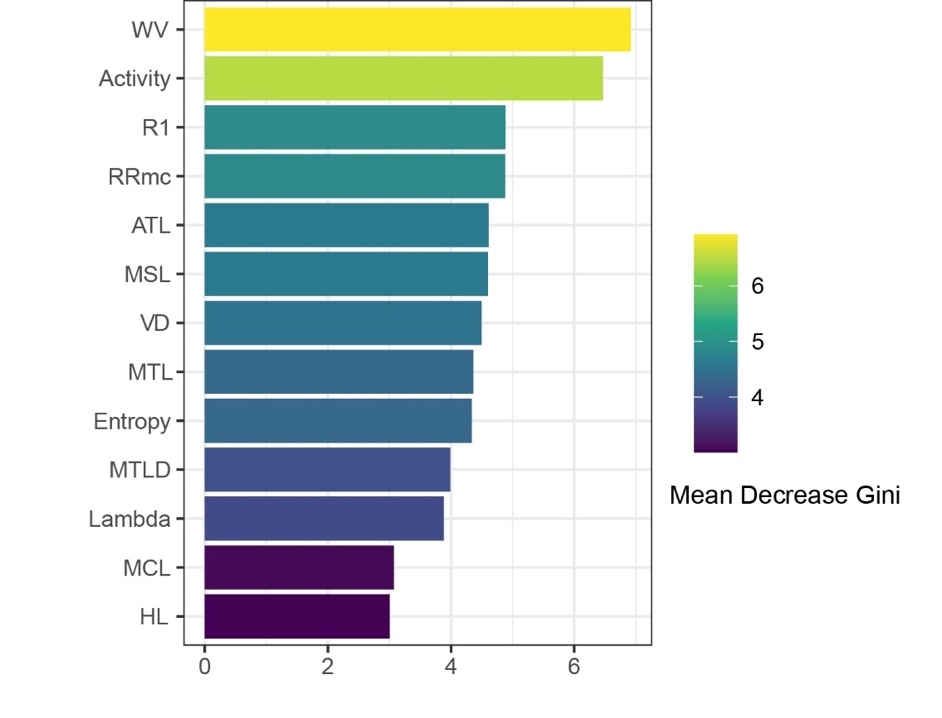

Table 3 provides a detailed breakdown of the accuracy decrease for each index in both non-translated and translated texts, along with the Mean Decrease Accuracy (MDA) and Mean Decrease Gini (MDG) scores. MDA represents the average reduction in model accuracy when a particular index is removed. A high value indicates that the feature is critical for the model’s predictive performance. This measure helps identify features that have the strongest impact on the model’s accuracy. MDG gauges the importance of each feature based on the Gini impurity criterion. In Random Forest models, each split in a tree contributes to reducing the Gini impurity, a measure of how often a randomly chosen element from the dataset would be incorrectly classified. A higher score for a feature suggests that it effectively separates classes at decision points. In this study, WV and Activity demonstrate the highest MDG (6.922 and 6.468, respectively), highlighting their strong role in differentiating translated from non-translated texts based on linguistic features. While MDA and MDG provide complementary insights into variable importance, we selected the MDG as the primary criterion for identifying important indices, owing to its effectiveness in quantifying how well each feature contributes to distinguishing between two categories of texts.

WV and Activity exhibit particularly pronounced differences between translated and non-translated sports news. A deviation in WV signals varying levels of writers’ control over lexical distribution. The prominence of Activity as a discriminative feature suggests distinct stylistic preferences for action or description. This finding aligns with observations from interpreting studies. For example, Jia and Liang (2020) reported significant variation in Activity across interpreting types. Similarly, prior studies have used WV to capture stylistic variation across genres or proficiency levels (Pan et al., 2015; Chen & Xu, 2019). Collectively, the strong importance of WV and Activity provides new evidence within specialised translation contexts that translation leaves a measurable stylistic imprint on the text.

| Indices | Accuracy decrease (non-translated) | Accuracy decrease (translated) | Mean Decrease Accuracy | Mean Decrease Gini |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WV | 9.772 | 6.924 | 11.312 | 6.922 |

| Activity | 7.076 | 6.122 | 8.898 | 6.468 |

| R1 | 4.197 | 3.671 | 5.235 | 4.885 |

| RRmc | 5.218 | 1.916 | 4.877 | 4.881 |

| ATL | 0.481 | 3.681 | 2.925 | 4.609 |

| MSL | 1.200 | 6.709 | 5.532 | 4.599 |

| VD | 2.178 | 3.568 | 4.005 | 4.497 |

| MTL | 3.679 | 4.948 | 5.874 | 4.363 |

| Entropy | 1.873 | 0.387 | 1.467 | 4.339 |

| MTLD | 4.973 | 2.740 | 5.341 | 3.988 |

| Lambda | 0.023 | 3.425 | 2.431 | 3.883 |

| MCL | 2.785 | 0.432 | 2.506 | 3.073 |

| HP | -0.742 | 1.649 | 0.610 | 3.004 |

Table 3. Variable importance metrics for non-translated and translated text classification

Figure 2 displays the MDG importance for each index used in the Random Forest model. WV and Activity stand out with the highest values, reaffirming their dominant role in distinguishing translated from non-translated texts. Beyond these top two features, other salient features include R1 and RRmc, followed by ATL and MSL, all of which contribute meaningfully to the model’s classification performance. Specifically, R1 and RRmc emerge as strong contributors, suggesting that differences in lexical vocabulary richness are key factors separating translated from non-translated texts. Likewise, ATL and MSL show notable importance, indicating that structural characteristics such as word and sentence length further differentiate two categories of texts. Overall, this ranking of features supports the incorporation of quantitative linguistic indices, which capture multiple dimensions of linguistic variation within the model.

Figure 2. Visualisation of variable importance based on Mean Decrease Gini

3.2 Comparing thirteen indices between non-translated and translated texts

To further explore the distinguishing indices between translated and non-translated texts, independent samples t-tests were conducted on 13 indices. These complementary tests aimed to validate whether the indices identified as important in the Random Forest model differ significantly between translated and non-translated texts. Results are summarised in Table 4.

| Index | Levene's test for equal variances (F) | df | t / Welch’s t | p-value | Cohen's d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WV | 3.214 | 118 | 3.736 | <0.001*** | 0.68 |

| Activity | 0.491 | 118 | 3.635 | <0.001*** | 0.66 |

| R1 | 0.235 | 118 | 2.697 | 0.008** | 0.49 |

| RRmc | 1.788 | 118 | 3.497 | 0.001** | 0.64 |

| ATL | 4.087* | 106.661 | -2.652 | 0.009** | 0.48 |

| MSL | 0.271 | 118 | 1.615 | 0.109 | 0.29 |

| VD | 6.150* | 109.493 | -1.873 | 0.064 | 0.34 |

| MTL | 0.175 | 118 | 1.339 | 0.183 | 0.24 |

| Entropy | 2.785 | 118 | 0.566 | 0.572 | 0.1 |

| MTLD | 0.001 | 118 | 1.574 | 0.118 | 0.29 |

| Lambda | 0.233 | 118 | -1.048 | 0.297 | 0.19 |

| MCL | 0.056 | 118 | -1.082 | 0.281 | 0.2 |

| HL | 0.042 | 118 | 0.447 | 0.656 | 0.08 |

Note. p < 0.05*, p < 0.01**, p < 0.001***.

Table 4. Comparing 13 indices between non-translated and translated texts

Prior to conducting the t-tests, Levene’s test for equality of variances was performed to determine whether the variances between translated and non-translated texts were equal for each index. For indices where Levene’s test was significant (p < 0.05), Welch’s t-test was used to adjust for unequal variances. The t-test analysis revealed significant differences in five indices: Writer’s View, Activity, R1, RRmc and ATL. These findings align closely with the Random Forest model, where these indices had high Mean Decrease Gini scores, highlighting their importance in distinguishing the two text categories.

Writer's View (WV) demonstrates a significant difference between translated and non-translated texts (t = 3.736, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.68). The positive t-value and significant p-value indicate that non-translated texts have a significantly higher WV compared with translated texts. Cohen’s d suggests a medium effect size, indicating that this difference is both statistically significant and practically meaningful. This finding is consistent with the previous Random Forest analysis, where WV has the highest Mean Decrease Gini score, making it the most important feature for distinguishing between translated and non-translated texts. Compared with translated texts, non-translated texts exhibit a WV that deviates more from the golden ratio, indicating that authors and content creators exert greater control over the use of function words and content words in their writing process, as well as a stronger emphasis on aesthetic considerations than translators.

Non-translated texts also show significantly higher Activity scores than translated texts. (t = 3.635, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.66). In the previous Gini analysis, Activity was the second most important feature. The t-test results further validate its significance, showing that non-translated sports news tends to be more active and dynamic, whereas translated texts are relatively more descriptive.

For R1, the t-test reveals a significant difference between non-translated and translated texts (t = 2.697, p = 0.008, Cohen’s d = 0.49). This is consistent with the Random Forest model, where R1 ranks among the top features, indicating a richer use of content words in non-translated texts. These findings support the simplification hypothesis, as evidenced by the significantly lower lexical richness (lower R1) in translated sports news compared to their non-translated counterparts.

The t-test indicates that non-translated texts have a significantly higher RRmc than translated texts (t = 3.497, p = 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.64). Aligning with the Gini analysis, where RRmc is also identified as a key feature, the significant positive t-value confirms that translated texts have higher word repetition and lower lexical diversity compared with non-translated texts. These results further support simplification hypothesis.

Average Token Length (ATL) is the only feature with a significant negative t-value (t = -2.652, p = 0.009, Cohen’s d = 0.48), indicating that non-translated texts tend to use shorter words. Levene’s test was significant (F = 4.087, p < 0.05), necessitating the use of Welch’s t-test. This finding corresponds with ATL’s importance in the Random Forest analysis, highlighting that shorter tokens are more prevalent in non-translated texts. Shorter words in non-translated texts are likely to enhance readability and accessibility for the target audience, whereas translated texts may include longer words to more accurately convey the meaning of the source texts. Contrary to the simplification hypothesis, these findings suggest that lexical complexity may not necessarily be subject to simplification but rather reflects an adaptation to genre-specific stylistic conventions (Bielsa & Bassnett, 2008; Li, 2024). Since the primary objective of news translation is to transmit information (Bielsa & Bassnett, 2008), translators or editors may adapt their lexical choices to ensure both faithfulness and completeness of the message (Li, 2024). From a functionalist perspective, such adjustments also serve to facilitate swift and comprehensive understanding for a broad readership (Liu, 2017; Mao, 2024).

The t-test results largely corroborate the findings from the Mean Decrease Gini analysis. Features like Writer’s View, Activity, R1, RRmc and ATL not only have high Gini importance scores in the Random Forest model but also show statistically significant differences between translated and non-translated texts. These consistent results across both methods highlight the robustness of these features in distinguishing between the two categories.

Other features, such as MTLD, Hapax Legomena Percentage (HL), Lambda, Entropy, Mean Sentence Length (MSL), Mean T-unit Length (MTL), Mean Clause Length (MCL) and Verb Distance (VD), did not show significant differences, suggesting that these indices do not effectively differentiate between translated and non-translated texts. This aligns with their relatively low Mean Decrease Gini scores, indicating their limited impact on classification.

At lexical level, the results for MTLD, HL, Lambda and Entropy indicate that translated and non-translated sports news exhibit similar levels of lexical diversity, balance between unique and repeated words, frequency structure and vocabulary dispersion, thereby supporting the normalisation hypothesis of translated language. These findings suggest that translators or editors may align lexical choices with conventional patterns in the target language, minimising deviations from norms found in non-translated texts.

At syntactic level, none of the traditional corpus-based indices, including MSL, MTL and MCL, shows significant differences, indicating similar syntactic complexity between translated and non-translated sports news. This also supports the normalisation hypothesis, implying that translated language conforms to syntactic structures typical of the target language rather than exhibiting simplification or increased complexity. VD approached significance (t = −1.873, p = 0.064), with non-translated texts tending toward slightly short distances between successive verbs. This might suggest a more dynamic and compact sentence structure in non-translated texts, although the difference is not statistically robust and warrants further investigation.

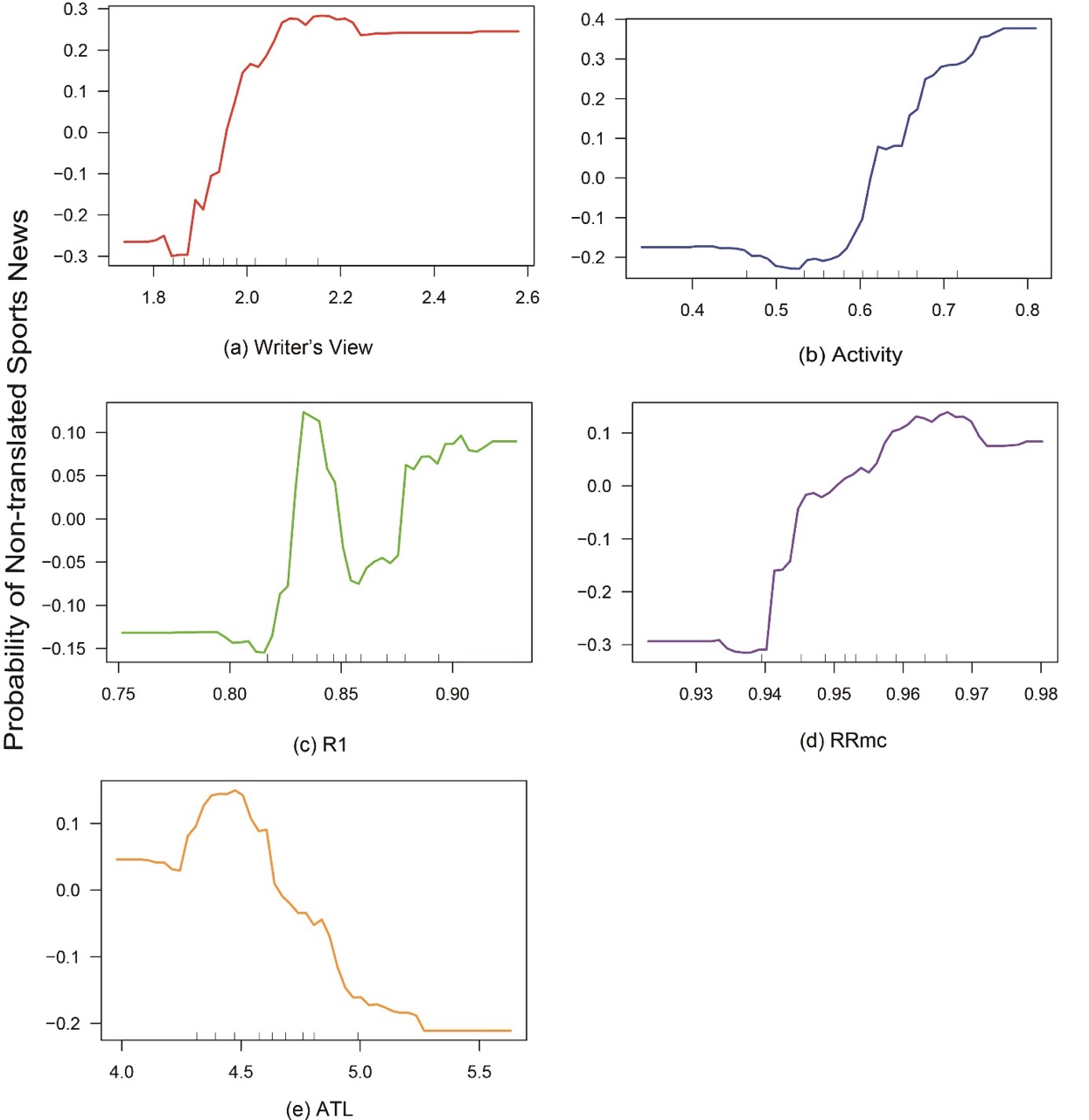

3.3 Partial Dependence Plots analysis of significant indices

Building upon the results of the t-tests, which identified WV, Activity, R1, RRmc and ATL as significantly different between translated and non-translated texts, we utilised Partial Dependence Plots (PDPs) to further examine how each feature influences classification outcomes. Generated from the Random Forest model, PDPs visualise net effect of each feature on the model’s predictions while holding all other features constant or averaging their effects out. This approach helps isolate the marginal effect of a single feature, providing clear insights into its standalone contribution to classification, independent of feature interactions. Figure 3 presents the effect of individual indices on the probability of classifying a text as non-translated, while controlling for all other indices.

As shown in Figure 3a, the probability increases significantly as WV scores rise, suggesting that non-translated texts tend to have higher WV scores. This reflects greater structural organisation and a stronger deviation from the ‘golden ratio’, highlighting the deliberate aesthetic choices and stylistic control exercised by the original writers. In contrast, translated texts, while faithfully adhering to the source text’s content, may exhibit higher self-organisation, potentially reflecting a loss of stylistic nuances introduced by translators.

Figure 3b demonstrates that higher Activity scores (indicating a higher verb-to-adjective ratio) correspond to an increased likelihood of a text being classified as non-translated. This suggests that non-translated texts are more dynamic and action-oriented, consistent with the characteristics of original sports news, which typically emphasise actions and events. In contrast, translated texts may lean toward a more descriptive and static style.

A more complex trend emerges in Figure 3c, where the probability of a text being classified as non-translated increases non-linearly once R1 surpasses approximately 0.85. This indicates that non-translated texts typically contain a higher proportion of content words, reflecting richer vocabulary usage. The greater lexical richness in non-translated texts highlights the creative flexibility of original authors, whereas translated texts may exhibit more constrained lexical choices, aligning with the simplification hypothesis.

Figure 3d reveals that as RRmc increases, so does the probability of classifying a text as non-translated, especially when RRmc exceeds 0.95. Higher RRmc values indicate lower word repetition, reflecting greater lexical diversity in non-translated texts. Conversely, lower RRmc values, typical of translated texts, suggest higher word repetition. This finding underscores the tendency of translated texts to rely on repeated words, likely driven by the need to maintain consistency with the source text, while non-translated texts demonstrate a broader range of word choices. These results echo the simplification hypothesis, particularly regarding reduced lexical diversity in translated texts.

A negative relationship is observed in Figure 3e for ATL, where longer average token lengths correspond to a lower probability of classifying a text as non-translated. This suggests that non-translated texts favour shorter words, likely reflecting a preference for directness and readability in original sports news. In contrast, translated texts incorporate longer words, which challenges the simplification hypothesis.

By isolating the effect of these features, PDPs not only reinforce the significance of indices identified in the t-tests but also provide deeper insights into the lexical and syntactic distinctions that characterise translated and non-translated sports news.

Figure 3. Partial dependence plots of five features and probability of non-translated sports news

4 Conclusion

This study investigated linguistic variations between Chinese–into–English translated and English non-translated sports news through a quantitative linguistic approach. Using a self-built comparable corpus and leveraging Random Forest analysis alongside statistical tests, we identified key features that distinguished these two text categories, shedding light on the nature of sports news translation and its implications for translation universals.

Among the thirteen linguistic indices examined, Writer’s View, Activity, R1, RRmc and ATL emerged as the most significant indices, as evidenced by their high Mean Decrease Gini scores. Compared to non-translated sports texts in English, sports texts translated into English from Chinese, exhibited significantly lower lexical density (lower R1) and lexical diversity (lower RRmc), supporting the simplification hypothesis. However, translated texts used more complex words (longer ATL) than non-translated texts, contradicting simplification expectations and underscoring genre-specific influences, as translators or (trans)editors may resort to longer words to ensure accuracy and faithfulness, or that domain-specific terminology (including metaphors) does not align with that simplification. These parameters most certainly form the basis of future research avenues.

Higher Writer’s View and Activity scores in non-translated texts suggested that original authors exercised greater control over structural organisation and favoured a more action-oriented style compared to translators. Additionally, translated texts demonstrated similar levels of MTLD, HL, Lambda, Entropy, MSL, MTL, MCL and Verb Distance to their non-translated counterparts, broadly aligning with the normalisation hypothesis.

This study has at least three implications. Firstly, it offers empirical insights into the ongoing debate on translation universals, notably in an underexplored genre such as sports news. The findings partially support both the simplification and normalisation hypotheses, while also highlighting the role of genre-stylistic conventions in shaping translation. Secondly, the integration of quantitative linguistic indices with machine learning methods, such as Random Forest analysis, demonstrates a potential approach for examining linguistic variations between translated and non-translated sports news. Thirdly, the findings also speak to the broader issue of English variation. The type of English represented by Xinhua output is not easily assigned to fixed categories such as British English or Chinese English, resonating with the view that English varieties are inherently variable.

Three limitations of the current study must be acknowledged. Firstly, despite efforts to ensure comparability in genre, time span and length between the BBC and Xinhua subcorpora, non-translated and translated English respectively, differences in specific news content, editorial practices, house styles and broader journalistic norms may have introduced variation beyond translation effects. Future research could use more closely matched sporting events and additional translation directions and language pairs. Also, although previous studies have pointed out that Xinhua’s English output often diverges from standard American or British norms and may therefore represent a separate Chinese-influenced variety of English (e.g., Alvaro, 2015; Li, 2024; Liu, 2017), the Xinhua English corpus may still involve Chinese translators as well as (near) native English-speaking editors. Yet, background information of its translators or editors is not publicly available. Secondly, potential correlations or interactions among linguistic indices may partially constrain the interpretability of PDPs. We acknowledge this as a methodological limitation and encourage future research to explore alternative interpretability methods under similar corpus settings. Thirdly, while adopting Random Forest validated via out-of-bag error estimation mitigates overfitting risks and supports the reliability of the findings, the relatively small corpus size and a single language pair and translation direction may limit the representativeness and generalisability of the results. Given the exploratory nature of this research, highly-controlled experiments and qualitative analyses on comparable content from identical sports disciplines as well as textual markers of translation universals are necessary to extend our findings.

In sum, this study demonstrates the effectiveness of a quantitative linguistic approach in profiling distinctive features of specialised translation, here in the domain of translated and non-translated sports news, while offering new evidence for translation universals in a genre-specific context.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant from the National Social Science Foundation of China awarded to Xinlei Jiang (Award Reference: 22CYY005). I sincerely thank the editors and anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and suggestions. I also thank my baby boy Xixi for accompanying me through the entire process of this paper, from being in my womb during writing to being in my arms during revision.

References

Al Kayed, M. M. (2023). The challenges facing translation students in translating sports idiomatic expressions from Arabic into English. International Journal of Arabic-English Studies, 24(1). 401–418. https://doi.org/10.33806/ijaes.v24i1.568

Altmann, G. (1978). Towards a theory of language. In G. Altmann (Ed.), Glottometrika 1 (pp. 1–25). Brockmeyer.

Alvaro, J. J. (2015). Analysing China’s English‐language media. World Englishes, 34(2), 260–277. https://doi.org/10.1111/weng.12137

Anthony, L. (2024). TagAnt (Version 2.1.0) [Computer software]. Waseda University. https://www.laurenceanthony.net/software

Anyawuike, O. S. O. (2023). Sports translation and interpreting: Football as a case study. Nigerian Journal of African Studies, 5(1), 107–112. https://www.nigerianjournalsonline.com/index.php/NJAS/article/view/3315/3229

Baines, R. (2013). Translation, globalization and the elite migrant athlete. The Translator, 19(2), 207–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/13556509.2013.10799542

Baker, M. (1993). Corpus linguistics and translation studies: Implications and applications. In G. Francis, M. Baker, & E. Tognini-Bonelli (Eds.), Text and technology: In honour of John Sinclair (pp. 233–252). John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/z.64.15bak

Baker, M. (1996). Corpus-based translation studies: The challenges that lie ahead. In H. Somers (Ed.), Terminology, LSP and translation studies in language engineering: In honor of Juan C. Sager (pp. 175–186). John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/btl.18.17bak

BBC. (n.d.). Sport. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/sport

Bielsa, E., & Bassnett, S. (2008). Translation in Global News (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203890011

Blum-Kulka, S., & Levenston, E. (1983). Universals of lexical simplification. In C. Færch & G. Kasper (Eds.), Strategies in interlanguage communication (pp. 119–139). Longman.

Boulton, A., & Cobb, T. (2017). Corpus use in language learning: A meta-analysis. Language Learning, 67(2), 348–393. https://doi.org/10.1111/lang.12224

Boynukara, E. (2017). On the importance of translation and interpretation in sports and the reflections of mistranslation. Journal of Sport and Social Sciences, 4(1), 1–6.

Breiman, L. (2001). Random forests. Machine Learning, 45(1), 5–32. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010933404324

Busemann, A. (1925). Die Sprache der Jugend als Ausdruck der Entwicklungsrhythmik: Sprachstatistische Untersuchungen. Fischer.

Callies, M., & Levin, M. (2019). A comparative multimodal corpus study of dislocation structures in live football commentary. In M. Callies & M. Levin (Eds.), Corpus approaches to the language of sports (pp. 253–269). Bloomsbury Academic. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350088238.ch-011

Chen, H., & Xu, H. (2019). Quantitative linguistics approach to interlanguage development: A study based on the Guangwai-Lancaster Chinese Learner Corpus. Lingua, 230, 102736. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2019.102736

Chen, R., & Liu, H. (2014). Quantitative aspects of Journal of Quantitative Linguistics. Journal of Quantitative Linguistics, 21(4), 299–340. https://doi.org/10.1080/09296174.2014.944327

Chen, Y. (2011). The translator’s subjectivity and its constraints in news transediting: A perspective of reception aesthetics. Meta, 56(1), 119–144. https://doi.org/10.7202/1003513ar

Chesterman, A. (2004). Beyond the particular. In A. Mauranen & P. Kujamäki (Eds.), Translation universals: Do they exist? (pp. 33–49). John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/btl.48.04che

Chesterman, A. (2008). Hypotheses about translation universals. In G. Hansen, A. Chesterman, & H. Gerzymisch-Arbogast (Eds.), Claims, changes and challenges in translation studies (pp. 1–13). John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Cvrček, V., & Chlumská, L. (2015). Simplification in translated Czech: A new approach to type-token ratio. Russian Linguistics, 39(3), 309–325. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11185-015-9151-8

Delaere, I., De Sutter, G., & Plevoets, K. (2012). Is translated language more standardized than non-translated language? Target, 24(2), 203–224. https://doi.org/10.1075/target.24.2.01del

Du, X. (2023). Lexical features and psychological states: A quantitative linguistic approach. Journal of Quantitative Linguistics, 30(3–4), 257–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/09296174.2023.2256211

Eris, E. (2020). Translation of political metaphors and intertextuality based on sports terms. Sosyal Bilimler Araştırmaları Dergisi, 15(1), 271–279. https://dergipark.org.tr/en/download/article-file/1166576

Fest, J. (2016). The register of sports news around the world—A quantitative study of field in newspaper sports coverage. In D. Caldwell, J. Walsh, E. W. Vine, & J. Jureidini (Eds.), The discourse of sport (pp. 190–208). Routledge.

Frawley, W. (1984). Prolegomenon to a theory of translation. In W. Frawley (Ed.), Translation: Literary, linguistic, and philosophical perspectives (pp. 159–175). University of Delaware Press.

Gafiyatova, E., & Pomortseva, N. (2016). The role of background knowledge in building the translating/interpreting competence of the linguist. Indian Journal of Science and Technology, 9(16), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.17485/ijst/2016/v9i16/89999

Ghignoli, A., & Torres-Díaz, M. G. (2015). Interpreting performed by professionals of other fields: The case of sports commentators. In R. Antonini & C. Bucaria (Eds.), Non-professional interpreting and translating in the media (pp. 193–208). Peter Lang.

Godwin-Jones, R. (2017). Data-informed language learning. Language Learning & Technology, 21(3), 9–27. https://doi.org/10.64152/10125/44629

Graesser, A. C., McNamara, D. S., Louwerse, M. M., & Cai, Z. (2004). Coh-Metrix: Analysis of text on cohesion and language. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 36(2), 193–202. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03195564

Hirsch, J. E. (2005). An index to quantify an individual’s research output. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 102(46), 16569–16572. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0507655102

Holtzhausen, L. J., Souissi, S., Al Sayrafi, O., May, A., Farooq, A., Grant, C. C., Korakakis, V., Rabia, S., Segers, S., & Chamari, K. (2021). Arabic translation and cross-cultural adaptation of Sport Concussion Assessment Tool 5 (SCAT5). Biology of Sport, 38(1), 129–144. https://doi.org/10.5114/biolsport.2020.97673

House, J. (2008). Beyond intervention: Universals in translation? Trans-kom, 1(1), 6–19. http://www.trans-kom.eu/bd01nr01/trans-kom_01_01_02_House_Beyond_Intervention.20080707.pdf

Huo, C., Li, Y., & Li, H. (2024). The reconstruction of the connotation boundaries of sports translation: An exploration based on ESP theory. Journal of Sports and Science, 45(5), 103–111. https://doi.org/10.13598/j.issn1004-4590.2024.05.004

Itaya, H. (2021). The sports interpreter’s role and interpreting strategies: A case study of Japanese professional baseball interpreters. In M. L. Butterworth (Ed.), Communication and Sport (pp. 137–160). De Gruyter Mouton. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110660883-008

Jackson, S. J., Brandl-Bredenbeck, H. P., & John, A. (2005). Lost in translation: Cultural differences in the interpretation of violence in sport advertising. International Journal of Sport Management and Marketing, 1(1–2), 155–168. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJSMM.2005.007127

Jia, H., & Liang, J. (2020). Lexical category bias across interpreting types: Implications for synergy between cognitive constraints and language representations. Lingua, 239, 102809. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2020.102809

Jia, J., Afzaal, M., & Naqvi, S. B. (2022). Myth or reality? Some directions on translation universals in recent corpus-based case studies. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 902400. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.902400

Jiang, J., Ouyang, J., & Liu, H. (2019). Interlanguage: A perspective of quantitative linguistic typology. Language Sciences, 74, 85–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langsci.2019.04.004

Jiang, X., Jiang, Y., & Hoi, C. K. W. (2022). Is Queen’s English Drifting Towards Common People’s English? —Quantifying Diachronic Changes of Queen’s Christmas Messages (1952–2018) with Reference to BNC. Journal of Quantitative Linguistics, 29(1), 1–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/09296174.2020.1737483

Jiang, X., Jiang, Y., & Zhang, X. (2024). Assessing effects of source text complexity on L2 learners’ interpreting performance: A dependency-based approach. IRAL-International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1515/iral-2024-0065

Kajzer-Wietrzny, M. (2015). Simplification in interpreting and translation. Across Languages and Cultures, 16(2), 233–255. https://doi.org/10.1556/084.2015.16.2.5

Kenny, D. (2000a). Lexical hide-and-seek: Looking for creativity in a parallel corpus. In M. Olohan (Ed.), Intercultural faultlines: Research models in translation studies I: Textual and cognitive aspects (pp. 93–104). St. Jerome.

Kenny, D. (2000b). Translators at play: Exploitations of collocational norms in German–English translation. In B. Dodd (Ed.), Working with German corpora (pp. 143–160). University of Birmingham Press.

Kenny, D. (2001). Lexis and creativity in translation. St. Jerome.

Khalaf, F. A. (2022). Assessing the translation of English metaphorical expressions in selected sport advertisements. Journal of Surra Man Raa, 18(73), 1415–1432.

Khedri, H., & Fumani, M. R. F. Q. (2016). Investigating the strategies used in translation of soccer idiomatic expressions from English to Persian based on the model proposed by Baker. Modern Journal of Language Teaching Methods, 6(6), 135–142.

Köhler, R. (2012). Quantitative syntax analysis. Walter de Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110272925

Köhler, R., Altmann, G., & Piotrovskiĭ, R. G. (2005). Quantitative linguistics: An international handbook. Walter de Gruyter.

Kortmann, B. (2021). Reflecting on the quantitative turn in linguistics. Linguistics, 59(5), 1207–1226. https://doi.org/10.1515/ling-2019-0046

Kubát, M., Matlach, V., & Čech, R. (2014). QUITA – Quantitative Index Text Analyzer. RAM-Verlag.

Laviosa, S. (1998a). Core patterns of lexical use in a comparable corpus of English narrative prose. Meta, 43(4), 557–570. https://doi.org/10.7202/003425ar

Laviosa, S. (1998b). The corpus-based approach: A new paradigm in translation studies. Meta, 43(4), 474–479. https://doi.org/10.7202/003424ar

Laviosa-Braithwaite, S. (1997). Investigating simplification in an English comparable corpus of newspaper articles. In K. Klaudy & J. Kohn (Eds.), Transferre necesse est: Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Current Trends in Studies of Translation and Interpreting (pp. 531–540). Scholastica.

Lei, L., & Liu, D. (2019). Research trends in applied linguistics from 2005 to 2016: A bibliometric analysis and its implications. Applied Linguistics, 40(3), 540–561. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amy003

Li, J. (2024). The Role of News Translation in Building and Countering Images of China [Doctoral dissertation, University College London].

Liu, H. (2017). An introduction to quantitative linguistics. The Commercial Press.

Liu, H., Zhao, Y., & Li, W. (2009). Chinese syntactic and typological properties based on dependency syntactic treebanks. Poznań Studies in Contemporary Linguistics, 45(4), 509–523.

Liu, K., & Afzaal, M. (2021). Syntactic complexity in translated and non-translated texts: A corpus-based study of simplification. PLOS ONE, 16(6), e0253454. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0253454

Liu, K., Liu, Z., & Lei, L. (2022). Simplification in translated Chinese: An entropy-based approach. Lingua, 275, 103364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2022.103364

Liu, N. X. (2017). Chinese media translation. In C. Shei & Z.-M. Gao, The Routledge Handbook of Chinese Translation (1st edn, pp. 205–220). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315675725-15

Liu, Y., Cheung, A. K. F., & Liu, K. (2023). Syntactic complexity of interpreted, L2 and L1 speech: A constrained language perspective. Lingua, 286, 103509. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2023.103509

Lu, X. (2010). Automatic analysis of syntactic complexity in second language writing. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics, 15(4), 474–496. https://doi.org/10.1075/ijcl.15.4.02lu

Luo, Q. (2010). Encoding the Olympics – Visual hegemony? Discussion and interpretation on intercultural communication in the Beijing Olympic Games. The International Journal of the History of Sport, 27(9–10), 1824–1872. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2010.481136

Mao, J. (2024). Study of sports translation from the perspective of functional equivalence. International Journal of Social Sciences and Public Administration, 4(2), 154–160. https://doi.org/10.62051/ijsspa.v4n2.21

Mauranen, A. (1999). Will “translationese” ruin a contrastive study? Languages in Contrast, 2(2), 161–185.

Mauranen, A. (2007). Universal tendencies in translation. In M. Rogers & G. Anderman (Eds.), Incorporating corpora: The linguist and the translator (pp. 32–48). Multilingual Matters.

McCarthy, P. M., & Jarvis, S. (2010). MTLD, vocd-D, and HD-D: A validation study of sophisticated approaches to lexical diversity assessment. Behavior Research Methods, 42(2), 381–392. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.42.2.381

McCarthy, P. M. (2005). An assessment of the range and usefulness of lexical diversity measures and the potential of the Measure of Textual Lexical Diversity (MTLD) [Doctoral dissertation, The University of Memphis].

McEnery, A. M., & Xiao, R. (2007). Parallel and comparable corpora: What are they up to? In G. Anderman & M. Rogers (Eds.), Incorporating corpora: Translation and the linguist (pp. 278–291). Multilingual Matters.

McIntosh, R. P. (1967). An index of diversity and the relation of certain concepts to diversity. Ecology, 48(3), 392–404. https://doi.org/10.2307/1932674

Melka, T. S., & Místecký, M. (2020). On stylometric features of H. Beam Piper’s “Omnilingual”. Journal of Quantitative Linguistics, 27(3), 204–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/09296174.2018.1560698

Milić, M. (2014). Process-oriented approach to translating sports research papers from Serbian into English. In B. Eraković (Ed.), Topics in translator and interpreter training: Proceedings of the Third IATIS Regional Workshop on Translator and Interpreter Training, 25–26 September 2014, Novi Sad, Serbia (pp. 71–86). Faculty of Philosophy, University of Novi Sad.

Monaco, E., Pisanu, G., Carrozzo, A., Giuliani, A., Conteduca, J., Oliviero, M., Ceroni, L., Sonnery-Cottet, B., & Ferretti, A. (2022). Translation, cross-cultural adaptation, and validation of the Italian version of the Anterior Cruciate Ligament–Return to Sport After Injury (ACL-RSI) scale and its integration into the K-STARTS test. Journal of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, 23(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10195-021-00622-7

Pan, X., Qiu, H., & Liu, H. (2015). Golden section in Chinese contemporary poetry. Glottometrics, 32, 55–62. https://glottometrics.iqla.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/g32zeit.pdf

Popescu, I. I. (2007). Text ranking by the weight of highly frequent words. In P. Grzybek (Ed.), Exact methods in the study of language and text (pp. 555–566). Mouton de Gruyter.

Popescu, I. I., & Altmann, G. (2007). Writer’s view of text generation. Glottometrics, 15, 71–81. Retrieved from https://www.ram-verlag.eu/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/g15zeit.pdf

Popescu, I. I., Altmann, G., Grzybek, P., Jayaram, B. D., & Vidya, M. N. (2009). Word frequency studies. Mouton de Gruyter.

Popescu, I. I., Čech, R., & Altmann, G. (2011). The lambda-structure of texts. RAM-Verlag.

Popescu, I. I., Čech, R., & Altmann, G. (2012). Some geometric properties of Slovak poetry. Journal of Quantitative Linguistics, 19(2), 121–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/09296174.2012.659000

Popescu, I. I., Čech, R., & Altmann, G. (2014). Descriptivity in Slovak lyrics. Glottotheory, 4(1), 92–104. https://doi.org/10.1524/glot.2013.0007

Popescu, I. I., Mačutek, J., & Altmann, G. (2009). Aspects of word frequencies. RAM-Verlag.

Pym, A. (2008). On Toury’s laws of how translators translate. In A. Pym, M. Shlesinger, & D. Simeoni (Eds.), Beyond descriptive translation studies: Investigations in homage to Gideon Toury (pp. 311–328). John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/btl.75.24pym

Rabadán, R., & Gutiérrez-Lanza, C. (2023). Interference, explicitation, implicitation and normalization in third-code Spanish: Evidence from discourse markers. Across Languages and Cultures, 24(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1556/084.2022.00223

Sandrelli, A. (2015). “And maybe you can translate also what I say”: Interpreters in football press conferences. The Interpreters’ Newsletter, 20, 87–105.

Sâsâiac, A., & Brunello, A. (2014). Translating sports media articles-an exercise of linguistic analysis. Intertext, 31(3–4), 205–214.

Schäffner, C., & Adab, B. (2001). The idea of the hybrid text in translation: Contact as conflict. Across Languages and Cultures, 1(2), 167–180. https://doi.org/10.1556/Acr.2.2001.2.1

Shannon, C. E. (1948). A mathematical theory of communication. Bell System Technical Journal, 27(3), 379–423. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1538-7305.1948.tb00917.x

Těšitelová, M. (1992). Quantitative linguistics. John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/llsee.37

Toury, G. (1995). Descriptive translation studies and beyond. John Benjamins.

Trosborg, A. (1997). Translating hybrid political texts. In A. Trosborg (Ed.), Text typology and translation. (pp. 145–158). John Benjamins.

Tuzzi, A., Benešová, M., & Mačutek, J. (Eds.). (2015). Recent contributions to quantitative linguistics. De Gruyter Mouton.

Valdeón, R. A. (2015). Fifteen years of journalistic translation research and more. Perspectives: Studies in Translatology, 23(4), 634–662. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2015.1057187

Wilcock, B. (2020). The framing and reframing of sports news through translation in a converged media organisation [Master’s dissertation, University of the Free State].

Williams, D. (2005). Recurrent features of translation in Canada: A corpus-based study [Doctoral dissertation, University of Ottawa].

Wu, K., & Li, D. (2021). Normalization, motivation, and reception: A corpus-based lexical study of the four English translations of Louis Cha’s martial arts fiction. In V. X. Wang, L. Lim, & D. Li (Eds.), New perspectives on corpus translation studies (pp. 181–199). Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-4918-9_7

Xia, Y. (2014). Normalization in translation: Corpus-based diachronic research into twentieth-century English–Chinese fictional translation. Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Xiao, R. (2010). How different is translated Chinese from native Chinese? A corpus-based study of translation universals. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics, 15(1), 5–35. https://doi.org/10.1075/ijcl.15.1.01xia

Xiao, W., & Sun, S. (2020). Dynamic lexical features of PhD theses across disciplines: A text mining approach. Journal of Quantitative Linguistics, 27(2), 114–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/09296174.2018.1531618

Xinhua News Agency. (n.d.). Sports. https://english.news.cn/sports/index.htm

Xu, J. (2024). Research on sports-related English translation from the perspective of communicative translation theory: Taking texts of the Beijing Winter Olympics as an example. Journal of Education, Teaching and Social Studies, 6(4), 25–32. https://doi.org/10.22158/jetss.v6n4p25

Yule, G. U. (1944). The statistical study of literary vocabulary. Cambridge University Press.

Yule, G. U. (2014). The statistical study of literary vocabulary. Cambridge University Press.

Zhang, H., & Yang, Y. (2024). Linguistic features and translation of English sports news. Pacific International Journal, 7(5), 140–145. https://doi.org/10.55014/pij.v7i5.711

Zipf, G. K. (1935). Psycho-biology of language. Houghton Mifflin.

Zörnig, P., & Altmann, G. (2016). Activity in Italian presidential speeches. Glottometrics, 35, 38–48. https://www.ram-verlag.eu/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/g35zeit.pdf

Zörnig, P., Stachowski, K., Popescu, I. I., Mosavi, M., Mohanty, P., Kelih, E., Chen, R., & Altmann, G. (2015). Descriptiveness, activity, and nominality in formalized text sequences. RAM-Verlag.

ORCID 0000-0001-9275-830X; e-mail: xjtujxl@126.com↩︎