Sports Interpreting: Mapping the Field to Even the Score

Franz Pöchhacker 1, University of Vienna

ABSTRACT

The role played by interpreters in the field of sports has not received much scholarly attention to date, and sports interpreting is not covered in any of the comprehensive reference volumes in translation and interpreting studies. This article presents a scoping review in an effort to map sports interpreting as a field of research. Based on a systematic compilation of published sources from several bibliographic databases, a thematic analysis is carried out to identify subjects and methods of investigation. In addition, empirical research reported in Master’s theses is presented to point to further lines of investigation. A mapping with regard to interpreting settings and levels of professionalism reveals sports interpreting as a paradigm case that shares most of the features characterising interpreting in general. This conceptual framework, in combination with the bibliographic groundwork, is intended to help overcome the current fragmentation of research on sports interpreting and serve as a foundation for articulating a research programme designed to fill in blank spots and expand on key themes of relevance to the field of interpreting studies at large.

KEYWORDS

Sports, media interpreting, non-professional interpreting, press conferences, football, baseball

1. Introduction

Interpreting has been practised through the ages in a wide range of social settings, from peaceful trade to belligerent expeditions and from missionary work to colonial administration. Sports have a similarly long history, with ample evidence dating back to Ancient times (Crowther, 2007). Unlike interpreting, however, sports activities were set, throughout much of history, within a given society and would not normally have involved encounters between individuals or groups of different ethnic and linguistic backgrounds. The Greek Olympic Games, beginning in 776 BCE, are a case in point: only athletes belonging to a Greek city-state and tribe were eligible to participate (2007, p. 46). Moreover, the various competitions, such as foot and horse racing and wrestling, involved only individual athletes, which foregrounded physical skill, prowess and stamina and kept the role of communication to a minimum. Ball games, found in many cultures, became popular only in the Greco-Roman period, and many team sports originated only in the nineteenth century (Cronin, 2014). Yet the Greek Olympics as a paradigm case of an institutionalised sporting festival already featured an essential characteristic of modern-day sports, which had gained ground when the games took place under Roman rule: they attracted large crowds of spectators who watched the sports events for entertainment.

In our time, the idea of watching sports for entertainment is inseparably linked to traditional mass media coverage of sports events, which reaches infinitely larger numbers of spectators than even the biggest stadium could accommodate on site. Media reporting on sports events, first in the press, then in live radio broadcasts and now particularly on television and webcast channels, may initially have served only national audiences, especially in large English-speaking countries, but cross-border competitions were held as early as the mid-nineteenth century (Cronin, 2014). This was followed by the founding of international bodies that took charge of organising such international events. Some of the best-known examples include the International Olympic Committee (IOC), founded in 1894, and the Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA), established ten years later.

Media coverage catering to the entertainment function of professional sports events is one of the main factors that have made communication a very prominent topic in sports, second only, perhaps, to sports-related business interests. This is also reflected in the scholarly literature about sport, where the topic is now dealt with in specialised journals such as Communication & Sport and the International Journal of Sport Communication, both launched in the last ten years, as well as in a recent handbook on Communication and Sport (Butterworth, 2021).

Mass media have assumed a crucial role in ‘communicating sport’, and doing so on an international scale. Yet, communication is needed not only about sport but also in sport, as most professional and mediatised sports have become part of a globalised industry in which athletes, coaches and managers very often move freely across national borders (e.g., Giulianotti & Robertson, 2007). This globalisation of sport is necessarily associated with a range of multilingual and cross-cultural communication practices, from the use of English as a lingua franca to various forms of translation.

The focus of this article is on a particular form of (human) translation labelled as ‘interpreting’ and characterised as the task of enabling cross-language communication or, more broadly, communication access, in real-time (e.g. Pöchhacker, 2022a). With regard to the two principal dimensions of communication in sport and of sport, the role of interpreting in sports will be explored, first, with regard to the contexts in which the need for interpreters arises, and second, with a focus on the ways in which the need for interpreter-mediated communication in sports are being met. In line with the stated goal of ‘mapping’ the field of sports interpreting, which has remained surprisingly underexplored in translation and interpreting studies to date, the initial questions guiding the present exploration are the following: Where, for whom and for what purpose is interpreting being used? And how and by whom is such interpreting performed?

Methodologically, this mapping effort will essentially be based on published sources and informed by established categories and conceptual distinctions in interpreting studies. It might best be characterised as a scoping review (Munn et al. 2018), given its aim to gauge the coverage of sports interpreting in the research literature and to identify key conceptual relations, methods and knowledge gaps. In its main, inductive move, the compilation and analysis of existing bibliographic information will first yield a quantitative account of the literature on sports interpreting, identifying types of publications, languages, authors and affiliations. This will be followed by a thematic analysis of the bibliographic corpus in an attempt to identify specific topics of investigation, also considering the methods employed in research on sports interpreting to date.

Based on the resulting characterisation of interpreting settings, including institutional contexts and stakeholders, communicative genres, interacting parties and interpreting modes, the focus will be narrowed to salient subjects that arise from the interplay of these various constituent factors. Given the rather uneven and ‘patchy’ coverage of the field in the publications compiled, further lines of investigation are identified and illustrated by examples of recent research done in Master’s theses under the author’s supervision. The systematic account, complemented by a set of subjectively chosen sources, is intended as a first step towards outlining a research programme for the field of interpreting studies that could cover some less charted areas of the discipline.

2. Sources

The assumption underlying the present analysis is that sports interpreting is not well established as an area of interest in interpreting studies and may even be largely unknown in society at large. As much as sports is ubiquitous, interpreting is not, or not nearly to the same degree. Given the close links between sports and the media, the latter is a useful point of departure in a search for relevant sources. This will be illustrated in Section 2.1 below by two vignettes which point to two typical manifestations of interpreting in sports before a more methodical approach to a review of published sources is described in Section 2.2.

2.1. Interpreters in the media

According to Diriker (2003), interpreters are made ‘visible’ in the media by such “generators of discourse” as “Big Events”, “Big Money” and “Big Mistakes” (p. 232), to which one could add ‘Big Names’ on account of some athletes’ personal fame. Two examples can serve to illustrate the interplay of these themes.

The first is set in big league baseball in the United States and centres on Japanese-born Ippei Mizuhara, who came to fame as the interpreter and assistant to Shohei Ohtani, a Japanese star player of a Los Angeles Major League team. Mizuhara worked for Ohtani until early 2024, when he was accused in a widely reported “interpreter scandal” of massively defrauding the star to pay off gambling debts (Axisa, 2024).

Compared to the criminal charge of multi-million dollar theft, punished by a five-year prison sentence, the second example of an interpreter’s wrongdoing entering the media limelight is rather benign and amusing. In early 2023, US alpine skier Mikaela Shiffrin, the most successful World Cup champion of all times, was interviewed right after yet another victorious race for Austrian television (ORF). The female journalist spoke to Shiffrin on site in English, and the interview was rendered in German for Austrian viewers by a TV moderator in the ORF studio. Shiffrin said she was feeling busy and tired, adding, “I’m kind of at an unfortunate time of my monthly cycle”. Whereas the interviewer responded with empathy (“I totally understand.”), the (male) moderator rendered the remark, with an excessive time lag, as the equivalent of “I don’t even have time to cycle, which I always do every month”. The interpreter’s faux pas was quickly circulated in social media, with gender-laden overtones, and led to a humorous response by Shiffrin herself.

These two vignettes provide useful anecdotal evidence of the very different circumstances in which interpreting in sports settings is carried out. In particular, they point to the issue of professionalism, or the lack thereof, in situations where sports-related communication requires linguistic mediation.

2.2. Systematic searches

Sporadic media attention notwithstanding, sports interpreting has remained largely invisible in the field of translation and interpreting studies. This assertion is based on the fact that sports interpreting is not covered in the field’s major reference publications. There are no entries for ‘sport(s)’ in the subject indexes, let alone the keyword lists, of the Routledge encyclopedias (Baker & Saldanha, 2020; Pöchhacker, 2015), nor is sports interpreting featured in the three major Routledge handbooks on interpreting (Mikkelson & Jourdenais, 2015; Albl-Mikasa & Tiselius, 2022; Gavioli & Wadensjö, 2023). The only exception is an entry for “sports coverage” in the subject index of the Routledge Handbook of Conference Interpreting (Albl-Mikasa & Tiselius, 2022), where interpreting in sports is mentioned several times in the chapters on press conferences (Sandrelli, 2022) and on media interpreting (Falbo, 2022). No such references can be found, however, in the lists of articles and subjects of the five-volume and online Handbook of Translation Studies (Gambier & van Doorslaer, 2021) published by John Benjamins.

Specific references do exist, as evident from the six entries on ‘interpreting’ or ‘interpreters’ in the list of 25 references provided in the call for papers for the special issue on “Sport(s) translation / translating sport(s)” (Declercq & van Egdom, 2024). Since it is not clear how that selection of references was compiled, this article adopts a systematic search strategy based on existing bibliographic databases. While such a bibliometric approach tends to favour quantification, it can supply a firm foundation for subsequent qualitative analyses with regard to relevant settings and salient topics.

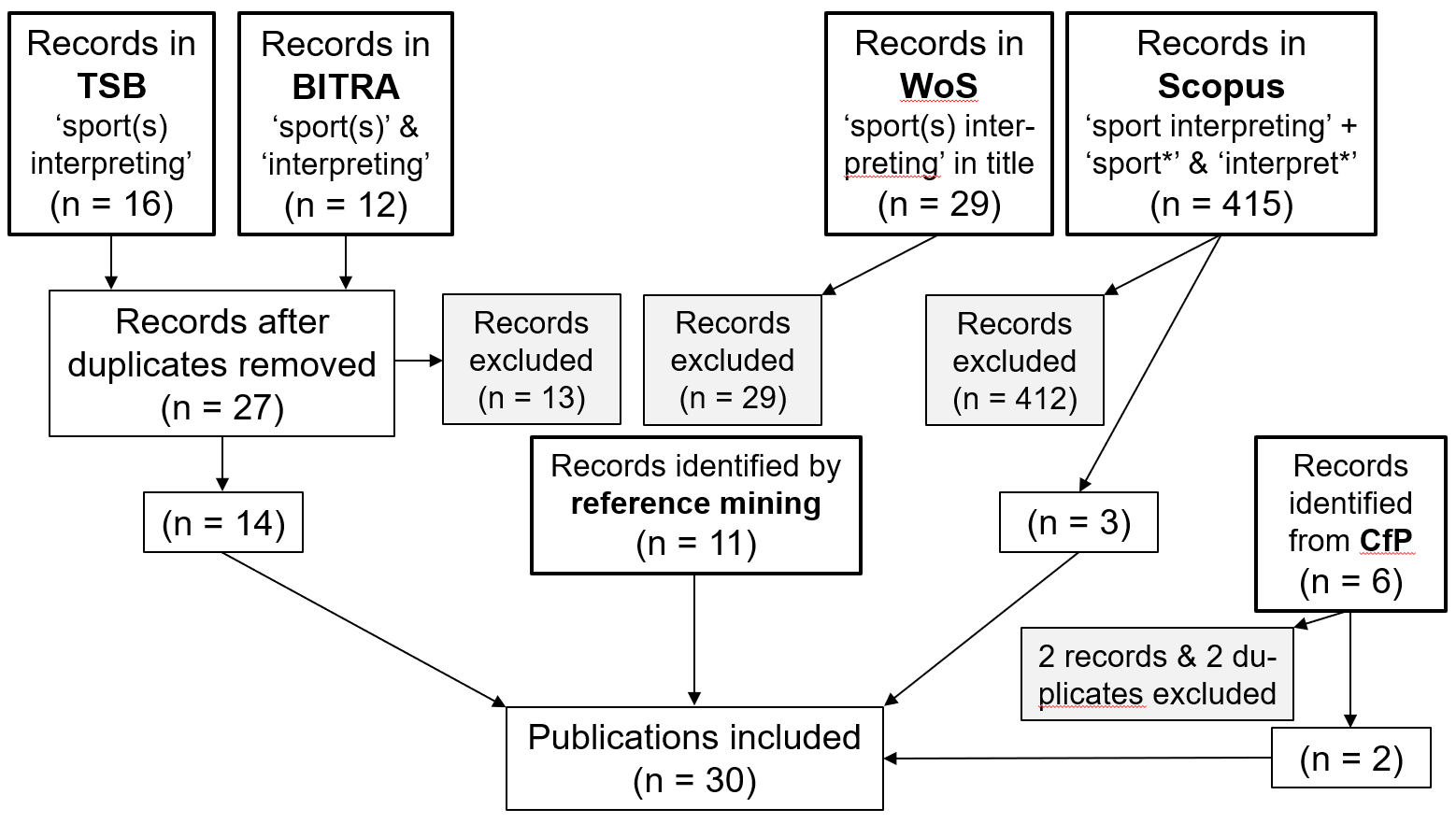

The field of translation and interpreting studies is served by two main bibliographic databases – John Benjamins’ Translation Studies Bibliography (TSB) and the Bibliography of Interpreting and Translation (BITRA) maintained at the University of Alicante. In the TSB, a search for the term ‘sports interpreting’ delivers thirteen hits. Six of these are relevant to the topic at hand, whereas the remainder mention ‘sport(s)’ in other contexts, such advertising, national identity or psychology, or with a focus on written translation. Unlike ‘sports translation’, interpreting can equally well be qualified by the singular form of sport, so both variants need to be considered. However, adjusting the search term to ‘sport interpreting’ yields only one item from the previous list, two new irrelevant ones and one reference to an edited volume that contains a distinctly relevant chapter on “interpreting football press conferences” (Sandrelli, 2012a). The book chapter as such, however, is not part of the results list, nor can it be retrieved with a more flexible query syntax. Appending an asterisk as a wildcard to both search words (sport* interpret*) yields a total of 21 entries, but no relevant items beyond the seven found in the queries for the compound noun.

Since the BITRA database has a systematic keyword structure, the query (in a range of languages) can conveniently be formulated by searching for ‘sport’ in combination with the top-level keyword ‘interpreting’. Rather similar to the search in the TSB, this yields a dozen entries. Here again, though, several of the matches turn out to relate not to the topic at hand but to theoretical approaches from the psychology of sports. Strikingly, only one of the eight items in the BITRA search results appears also in the list of seven entries retrieved from the TSB – and vice versa. In other words, the results of querying the two main bibliographic databases of translation and interpreting studies overlap in only a single item – a journal article by Roger Baines (2013). While this complementarity makes for a higher count of relevant references, it also raises concerns regarding reliable access to the collected stocks of research-based knowledge in translation and interpreting studies. A case in point is the observation that querying the BITRA holdings not as described above but with the same syntax as used in the TSB (i.e., sport* interpret*) produces more than twice as many hits. Although most of the 28 results prove insufficiently related to the topic, there is an additional entry for Baines (2012) as well as three additional ones from the special issue of Traduire, a French professional journal, of which only one article had been retrieved with the earlier query. As it is debatable whether these contributions by professionals, including an interview, should be considered on a par with articles in peer-reviewed journals, the total count for the core corpus ultimately remains at fourteen.

Fourteen publications constituting the bibliography for the topic of sports interpreting seems like a rather narrow foundation for a thematic analysis. Three options for extending the corpus were considered: deepening the search in the BITRA and TSB databases by following up on author names and keywords; mining the references of the retrieved publications for additional relevant items; and taking the search to a much broader level by conducting it in the two most comprehensive databases for scientific literature – the Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus. All of these steps were taken, as briefly summarised below.

The first option seems feasible for the fifteen names associated with the entries retrieved from the TSB and BITRA collections but proves more cumbersome than productive when implemented within the respective database. A query for ‘Roger Baines’ in the TSB, for example, yields six hits, of which only the two previously found items are relevant. On the other hand, TSB queries for author names like ‘Harris’, ‘Napier’ and ‘Wang’ require considerably greater effort, as do similar searches in the BITRA database for ‘Antonini’, ‘Falbo’ and ‘Sandrelli’. Yet even name searches across the two databases are of little avail, given the limitations of their respective design and structure – as seen with the entry for Baines (2012). On these grounds, the idea of embarking on detailed follow-up searches for keywords in publication titles was discarded in favour of reference mining within the fourteen sources already compiled.

That effort proved only moderately successful. A total of eleven references beyond the fourteen-item core corpus were identified. These include two MA theses and three additional references for ‘Sandrelli’. References to earlier work are relatively sparse and often limited to self-citations. Significant exceptions include references to the pioneering corpus-based work of Straniero Sergio (2003) on interpreting in Formula 1 press conferences and, more unexpectedly, to the Innsbruck Football Research Group investigating communication in “multilingual football teams” (Lavric & Steiner, 2012). Finally, a reference to video-mediated remote simultaneous interpreting during the 2014 FIFA World Cup (Seeber et al., 2019) brings the corpus total to 25 entries.

Beyond working with the references already found, the option of additional searches in much more comprehensive bibliographic databases was also pursued – with disappointing and disillusioning results.

In the Web of Science Core Collection, there are 12,500 matches for ‘sport(s) interpreting’ when searched in all fields, but only 29 when the query is limited to the title field (accessed 22.11.2024). None of these have any relevance to the topic at hand, as was the case also for the wider search for ‘sport* (and) interpret*’ in document titles. Screening the 175 items retrieved by that search shows that matches are based, almost without exception, on the use of ‘interpreting’ or ‘interpretation’ in the hermeneutic sense, even in title phrases as promising as “interpreting television sports” (WOS:000209805900033) or “sports event interpretation” (WOS:000471233200074). When ‘translation’ is added to the query in the topic field, there is only a single result – a reference to a 2017 paper by a Chinese author on “sports English interpreting” in the proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Education and Sports Education (WOS:000418204100009). Regrettably, the abstract, which also mentions “football English interpretation”, is barely intelligible; there is no mention of empirical research, and the eleven garbled references are limited to standard texts about translation and interpreter training. Neither the doi nor the ISBN of the proceedings volume serve to retrieve the publication.

In Scopus, a search for ‘sports interpreting’ as an exact phrase produces no matches, whereas ‘sport interpreting’ yields a single matching entry (Eftekhar et al., 2024). A broader search, for ‘sport* AND interpret*’ in titles, abstracts and keywords, finds some 9,500 documents (accessed 22.11.2024). This count is reduced to 414 when ‘language OR translation’ is added to the query. Once again, however, a detailed review of all records shows that nearly all matches include the words ‘interpreting’ or ‘interpretation’ used in the hermeneutic sense. Nevertheless, there are five notable exceptions: Aside from three journal articles that are part of the core corpus (Alonso Araguás & Zapatero Santos, 2019; Locker McKee & Napier, 2002; Sandrelli, 2015), the Scopus database also includes two book chapters by Turkish authors – one on “translation and interpreting in sports contexts” in Turkey (Uyanık, 2017) and another one on “the training of sign language interpreters for deaf sports” (Okyayuz & Erzanci Durmuş, 2022). Thus, unlike the search in the WoS Core Collection, Scopus serves to add another three entries to the list of sources.

Figure 1: Summary of data charting process

A final step in the corpus-building process (summarised in Figure 1) was to go back to the list of six interpreting-related references provided in the editors’ call for papers (Declercq & van Egdom, 2024). Discarding two items reflecting questionable scholarship and a lack of editorial oversight (i.e., a barely readable text with corrupted references in the Nigerian Journal of African Studies and an “essay” comparing sports and medical interpreting in a journal of “Literary Study”), there are two matches with entries in the core corpus of 14 (Ghignoli & Torres Díaz, 2016; Sandrelli, 2015) as well as two items not found in any other searches: the book chapter by Itaya (2021), erroneously listed as a journal article, and the journal article by Demiray Akbulut and Saba (2023), listed with author names reversed. Adding these two references brings the corpus total to 30.

3. Findings

The 30 publications on sports interpreting included in the present review are listed in Table 1 with bibliometric features such as the year, type and language of publication and the national context in which sports interpreting was investigated. (The full bibliographic entries are included the References, marked with an asterisk.) The presentation of findings will begin with a summary of bibliometric characteristics and proceed to an analysis in response to the main research questions regarding settings, genres and interpreting modes.

Table 1: List of publications reviewed

3.1. Bibliometric features

The publications under review roughly date from the past two decades, from 2002 to 2024. After the more sparsely covered initial years, the distribution is fairly even from 2011 to 2024, with an average of two publications per year (median: 2016). The mode is 2012, with four items listed for that year. With regard to type of publication, there are more book chapters (16) than journal articles (12), and two graduation theses, both written in languages other than English (Italian and Spanish). With 25 out of 30, English obviously predominates as the language of publication. With regard to authorship, 19 publications are by single authors, only two of which have more than one entry: Baines (3) and Sandrelli (5).

3.2. Settings

The notion of setting tends to be rather loosely defined but nevertheless serves as one of the most frequent descriptive categories in interpreting studies (see Grbić, 2015). It is used here for a characterisation of sports interpreting as an area of study by combining top-down distinctions with the themes emerging from the inductive analysis.

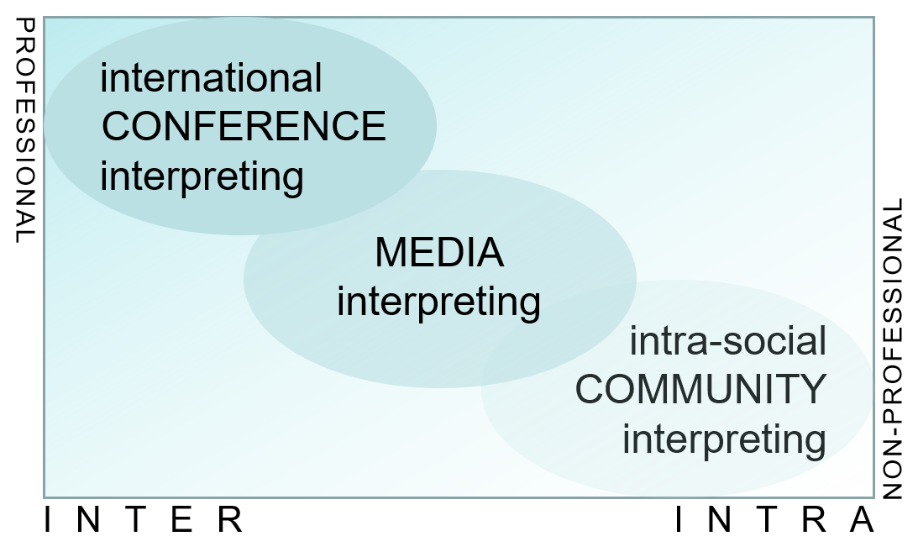

The most common broad distinction is between interpreting at international conferences and organisations, which achieved a high degree of professionalisation in the 20th century, and interpreting in the institutions and public services of a given society, often referred to as community interpreting. Whereas the former, generally referred to as conference interpreting, tends to be done as a career by highly trained (and paid) professionals, the latter is often associated with a lack of training and professionalism, especially when it is further distinguished, on pragmatic rather than conceptual grounds, from legal interpreting, for which certain regulations and standards are in place in many countries. As argued in Pöchhacker (2022b, p. 16), the flat opposition between conference and community interpreting can be enriched by a distinction on two different levels – between events in the international versus the intra-social sphere, and between conference-like and dialogue situations as two different “constellations of interaction”. International conference interpreting is then juxtaposed with community-based dialogue interpreting as the two prototypical domains of interpreting, which also allow for other types, such as international dialogue interpreting (e.g., in high-level diplomacy) and conference interpreting within a given (multilingual) society, including communication with deaf or hard-or-hearing people.

Based on the analysis of the publications in the corpus, sports interpreting is part of the work of both highly professional conference interpreters, typically working in simultaneous mode, and untrained bilinguals taking on the role of interpreter in a variety of communicative scenarios. An area of conference interpreting in the field of sports that seems to be largely overlooked, even though it is evident from the institutional perspective mentioned in the Introduction, are meetings of the major international bodies organising big sports events. The IOC, for instance, maintains its primary official language, French, along with English and the language of the country hosting the Olympic Games. FIFA even has four official languages (English, French, German and Spanish) and additionally uses Arabic, Portuguese and Russian for its annual Congress. As Harris (2017) emphasises, “an important part of [sports interpreting] is actually served by Professional Expert conference interpreters” (p. 41). In the same vein, Sandrelli (2015) states that “FIFA and UEFA have their own Chief Interpreters who recruit the conference interpreters with the required language combinations” (p. 92), and Seeber et al. (2019) show how remote simultaneous interpreting was implemented at the FIFA 2014 World Cup.

At the same time, with reference to the Olympics, Harris (2017) draws attention to “the army of other interpreters at the Games” – “Liaison Interpreters” who “aren’t engaged as interpreters and they aren’t recognized as such” (p. 41). This point is also made, with impressive figures, by Wang and Zhang (2011) and Itaya (2021) for the 2008 Beijing and the 2012 London Olympics, with 2,500 and 700 volunteer liaisons, respectively. Harris mentions athletes assisting fellow athletes in baseball, recalling a 2012 blogpost about such a chance interpreter being given an award in Japan. The fact that major sports teams have, for many decades, recruited players – as well as coaches – from other national and linguistic backgrounds (like Ohtani in US baseball, but much more so in the top football leagues) has been a focus of scholarly attention for some time. Bulut’s (2016) work on sports interpreting in Turkey, which includes the earliest reference to the term in a 2011 conference paper, is particularly worth mentioning. Noting that “sports interpreting is a popular job mainly at football clubs” (p. 3), she observes that “liaison” (dialogue) interpreting in less formal settings, such as “in a field training, locker room or informal meeting”, is closer in nature to “interpreting in the community” (p. 4), for which she refers to empirical work done in a 2015 MA thesis by Uyanık.

Pioneering work on “the globalized football team” was also done from a sociolinguistic perspective by a research group at the University of Innsbruck (Giera et al., 2008). Based on empirical work in the 2009 graduation thesis by Steiner on communicative situations and strategies in a multilingual team, Lavric and Steiner (2012) characterise the respective mediation practices as community interpreting and state: “ce ‘community interpreting’, là où il est possible, constitue […] la solution la plus courante et la plus économique aux problèmes langagiers du football” (p. 25; see also Lavric & Steiner, 2017). This work is also acknowledged by Baines (2013) and Sandrelli (2015) and taken up more extensively in the UEFA case study by Alonso Araguás and Zapatero Santos (2019).

On this basis, sports interpreting can be said to extend across the entire spectrum from highly professional conference interpreting to non-professional or lay interpreting in community settings, which include sports-related communication within a multilingual team as well as the extra-professional communication needs of what Baines (2013, 2018) calls “the elite migrant athlete”. For the range of sports interpreting activities, the horizontal spectrum of interpreting settings (Pöchhacker 2022b, p. 17) therefore combines with a vertical axis, or cline, of professionalism, as illustrated in Figure 2, which also features media interpreting (as defined, e.g., in Pöchhacker 2010) as a central setting that requires more detailed attention.

Figure 2: Sports interpreting settings

The activities in and for which interpreters of one type or another may be needed all come under the heading of ‘doing’ sports – whether by organising competitions and big events and managing athletes and teams or by actually and physically engaging in sports. To this must be added the task of presenting such ‘sporting’ to a wider public. This ‘reporting’, while still done also in print, is nowadays done in particular via digital mass media, and first and foremost through live television broadcasts and streaming. Indeed, it is this mediatisation as well as globalisation that has made (some) sports big business, and there is a sense in which global sports and media have become inseparably linked (see Butterworth, 2021). Although media coverage of actual sporting events, such as the Olympics or World Cup football games, relies on national broadcasters’ commentators, such broadcasts require media accessibility services such as live subtitles for the deaf and hard-of-hearing. On the other hand, interpreting needs typically arise in press conferences and interviews surrounding the events. The specific arrangements for such interpreter-mediated press conferences are among the main topics of research discussed further below. At this point, it will suffice to note that media interpreting is a significant setting of sports interpreting, occupying an intermediate position between international conference and community-based dialogue interpreting. It is closely related with the former through its international content and the press-conference format – as reflected in the somewhat unusual title of Falbo’s (2022) handbook chapter (“Media conference interpreting”). At the same time, it shares key features of the latter, such as interactive dialogue in the question-and-answer (Q&A) session that forms the crucial part of press conferences and the fact that the interpreting is done for the broadcaster’s national (domestic) audience.

3.3. Salient subjects

Based on the thematic analysis of the bibliographic corpus, televised press conferences stand out as the type of communicative event for which sports interpreting practices have been analysed most widely and thoroughly. Media interpreting of press conferences was first described and submitted to a corpus-based analysis by the late Francesco Straniero Sergio (2003), whose legacy is still in evidence. His pioneering corpus-based approach was adopted in numerous studies, in Italy as well as other countries. More specifically, his linguistic and translational analysis of Formula 1 press conferences given by drivers at the end of Grand Prix (GP) races was followed up in subsequent studies (e.g., Pignataro, 2011), as were his findings regarding (professional) media interpreters’ “emergency strategies”. The importance of Straniero Sergio’s (2003) groundwork is explicitly acknowledged by Sandrelli (2012a), whose publications on football press conferences make her stand out as the most prolific author in the field of sports interpreting to date. Not surprisingly, Sandrelli’s work informs many Master’s theses, including those by Maselli (2013) at UNINT Rome and Lorca Antón (2015) at the University of Alicante, and is also referenced by Demiray Akbulut and Saba (2023), who give special attention to press conferences in their account of “football interpreting in Turkey”.

Interpreter mediation in press conferences and the related genre of media interviews can take different forms, depending on language needs and media attention. A combination of whispered and consecutive interpreting on site is a basic format when one or more other-language speakers are involved (e.g., Itaya, 2021; Sandrelli, 2015). Live-broadcast press conferences of big events may be served by professional interpreters recruited by the organisers to work on site or remotely (e.g., Seeber et al. 2019). Quite typically, though, on-site interaction is in English only, and the (simultaneous) interpreting is provided only for national broadcasters’ audiences from the studio (see Sandrelli 2022, p. 84), for which Falbo (2012, p. 164) coined the term “simultaneous interpreting in absentia”. When interpreting is used on site, TV interpreters will be required to take relay (Sandrelli, 2012a, 2017).

Both the particular interpreting set-up and the press-conference format in general give rise to more specific topics of research – such as relay interpreting arrangements, which have however not been studied in any detail. Rather, interest tends to centre on the Q&A session for its interactional dynamics. Thus, turn-taking was investigated already by Straniero Sergio (2003) and most recently by Suarez Lovelle (2024). As in other dialogue-interpreting scenarios, the interpreter’s ‘role’, in the Goffmanian sense of participation status and footing, is a focus of analysis, as seen, for instance, in Itaya’s (2021) study of “baseball interpreters”.

A broader and more fundamental topic, which is also best studied on the basis of corpora of authentic interpreter-mediated discourse, is quality. Beyond Straniero Sergio’s (2003) early corpus-based work on source–target correspondence in Formula 1 GP press conferences, cases of “mistranslation” and different kinds of interpreter errors were analysed in media reports on interpreter-mediated interviews by Baines (2013) and Alonso Araguás and Zapatero Santos (2019). The topic of quality is closely connected with (TV interpreters’) working conditions (e.g., Jiménez Serrano (2011) and with the strategies interpreters use to cope with the special challenges of media interpreting assignments.

The topics of quality and strategy use link up, in turn, with a key dimension of the sports interpreting ‘map’ shown in Figure 2 – that is, the professional status of the individual doing the interpreting. As seen in the vignette about Shiffrin’s ‘cycle’ in Section 2.1, simultaneous interpreting for live broadcasts may also be done by TV commentators. This is exemplified for Spanish journalist-interpreters of motorbike races by Ghignoli and Torres Díaz (2016), who also test whether students (and future graduates) of interpreter-training programmes are skilled enough for the task. This points to yet another major theme of research on sports interpreting, namely, the qualifications required for this professional profile and the training needed to perform in that capacity.

As suggested in Figure 2, the qualifications for interpreting in sports are not fixed but vary depending on the setting and the scenarios of interaction. When the focus is on the communication needs of individual migrant athletes and multilingual teams, non-professional interpreting, by a fellow athlete or a personal interpreter or assistant (Lavric & Steiner, 2012), is the norm. As Itaya (2021) found in her interviews with baseball interpreters and players, personal interpreters are hired and appreciated not so much for their cognitive and linguistic skills as for their social (interpersonal, sociocultural) mediating role. An understanding or even love of the sport is taken as a given, so a profound knowledge of the subject-matter, including the field’s terminology and jargon, is an essential criterion.

When a higher level of interpreting skills is required and practitioners seek to develop a professional profile, training becomes a subject of inquiry. This is seen in research on the market for sports interpreting (e.g., Lorca Antón, 2015) and on sports interpreting as a “profession” in particular countries, such as Japan (Itaya, 2021) and Turkey (Bulut, 2016; Demiray Akbulut & Saba, 2023). In this regard, mega events such as the Olympic Games attract special attention. Wang and Zhang (2011) offer a detailed account of the way a foreign-studies university in Beijing prepared large numbers of “community interpreters” for the 2008 Games, with training and service provision also encompassing remote interpreting via the telephone. No less significant is the proposal by Okyayuz and Erkazanci Durmuş (2022) for the training of sign language interpreters for deaf sports. While in mediatised elite sports there is little concern, if any, for persons with special needs, the Paralympic Games represent an important counterweight, as do efforts to train sign language interpreters, also for International Sign (Locker McKee & Napier, 2002), not only for sports(-related) events but also for making them accessible through media broadcasts.

In summary, the list of subjects that have been dealt with in research on sports interpreting to date is long and varied, despite a relatively narrow range of events (Olympics, FIFA World Cup, Formula 1 GP), sports (football, baseball, racing) and scenarios of interaction which has been shaped not least by the availability and accessibility of data in audio-visual media.

One way of extending the range of events and sports as well as methodological approaches is to examine Master’s theses completed in degree programmes for interpreter education for their potential to contribute to the body of empirical research. This will be shown in the following section, which is intended to complement the systematic search-based account by a brief discussion of a purposive selection of noteworthy examples.

4. MA-level groundwork

The fact that two out of the 30 texts in the systematically compiled bibliographic corpus – Lorca Antón (2015) and Maselli (2013) – are Master’s theses is significant in itself. Moreover, close reading of the literature reveals many additional examples. Lorca Antón’s (2015) bibliography, for instance, contains several entries for MA-level graduation theses. Another noteworthy case is the 2009 thesis completed at the University of Innsbruck by Steiner, who went on to publish with her supervisor, Eva Lavric (e.g., Lavric & Steiner, 2012), and completed a doctoral dissertation in 2014 (see Lavric & Steiner, 2017). Such recognition of MA-level groundwork is not always given to the same degree. Sandrelli (2012a), for one, acknowledges the contribution of Maselli (2013) to her FOOTIE (Football In Europe) corpus; on the other hand, the 2015 MA thesis by Uyanık, written in Turkish, is cited for important content by her Turkish colleagues (Demiray Akbulut & Saba, 2023), whereas the book chapter published in English (Uyanık, 2017) is not.

In order to illustrate the considerable potential of empirical research done in Master’s theses, I would like to extend the list of such sources by some examples, mainly from my own (Austrian) institutional context. As will be seen, some of these follow established pathways on the current map, whereas others venture into new scenarios and topics.

Among the MA theses on sports interpreting completed under my supervision, the analysis of Formula 1 GP coverage is the most popular line of research, with four theses over the past seven years. Fiorito (2017) analysed 15 English podium interviews (i.e., post-race interviews with the top-three drivers) interpreted simultaneously on Italian television. While her thematic focus – on (fast-paced) turn-taking and the (professional) interpreter’s coping strategies – is not new, she presents her transcriptions in score format (using the software EXMARaLDA) to better reflect the time course of source and target-language speech. This method is also used in Kraudinger’s (2024) analysis of ten English podium interviews of the 2019 GP season interpreted by an ORF journalist. The earlier study by Nußbaum (2018) compared the performance of two different journalist-interpreters on ORF in five interviews of the 2016 season. A direct comparison of professional and what might best be called para-professional simultaneous interpreting from the studio was undertaken by Pfaller (2020), who analysed the complete coverage of the 2019 Brazilian GP in both ORF and RTL, also including a broader focus on the two broadcasters’ translation policy.

A more obvious direction in which to extend the body of available research is to explore interpreting in different sports. Although tennis is mentioned in some of the literature (e.g., Geens, 2009; Jiménez Serrano, 2011), the Master’s thesis by Schmol (2021) is the first to offer a comprehensive analysis: 25 broadcasts of international tennis tournaments by three different TV channels are analysed with a focus on the simultaneous interpreting provided by commentators. A notable example of going farther afield is the case study by Oreški (2016), who describes interpreting practices at an Angling World Championship in Croatia in her MA thesis at the University of Graz. She adopted a fieldwork approach triangulating findings from the analysis of documents, a survey among participants, two semi-structured interviews with interpreters and an in-depth interview with the organiser.

A fieldwork approach with participant observation or, rather, observant participation also characterises studies of language policy and interpreting arrangements at the Olympics. Coincidentally, two Master’s theses were devoted to the Special Olympics World Winter Games held in Austria in 2017. Working as a “delegation liaison assistant” (DAL) herself, Müllebner (2017) combined unstructured observation and semi-structured interviews to describe the work setting and identify its specific challenges. Aiming for a broader coverage of individual experiences, Wolfbauer (2018) surveyed fellow DALs with an online questionnaire, both before and after the event. Based on responses from more than half of the 220 DALs, she draws up a detailed account of their background and motivation as well as the broad range of their tasks and associated challenges.

In MA theses and in sports interpreting research more generally, quantitative surveys seem much less common than the analysis of multimodal corpora of audio-visual material and multi-method fieldwork. This is due, in large measure, to the lack of a well-defined population. Aside from Lorca Antón (2015), who managed to survey 11 professional interpreters working in sports, a noteworthy example is the MA thesis by Kootz (2014) completed at the University of Leipzig. Based on responses from over 50 professional interpreters, he reports a wealth of data on the German sports interpreting market, including types of events (chiefly press conferences and interviews), sports (chiefly football) and working modes (chiefly simultaneous, with a sizeable share of consecutive).

The examples above amply demonstrate the potential of MA theses for research on sports interpreting. Many students, mostly in their early twenties, display great affinity with sports and may welcome the opportunity to study what they are passionate about and often actively involved in. And despite declining enrolment in interpreter education programmes, Master’s students in university programmes requiring a substantial thesis for graduation are still numerous. Admittedly, the requirements and standards for graduation theses vary widely (as do those for peer reviewing of scholarly papers, for that matter), and substantial guidance and support from supervisors are required to ensure methodological rigour and reliable findings. Notwithstanding their limitations, the examples discussed in this section and earlier in this article serve to show that MA theses can be a source of valuable insights for sports interpreting as an underresearched field.

5. Conclusion

The aim of the present article was to find out where, for and by whom, how and for what purpose interpreting is done in sports. The answers, derived from the analysis of a systematically compiled set of publications as well as a purposive selection of MA theses, are difficult to summarise. Sports interpreting is practiced in a great diversity of settings, setups and institutional contexts by individuals with very different qualifications for users ranging from individual (‘migrant’) athletes to nationwide broadcast audiences. Given the paucity of published research, which also transcends disciplinary boundaries, it is hard to discern a clear pattern of findings. Nevertheless, some important broader conclusions can certainly be drawn.

The first main conclusion from the review of systematically compiled publications concerns the underlying bibliometric approach. Even though the bibliographic search was based on the field’s two most important specialised databases, coverage of sports interpreting was found to be incomplete and, more worryingly, highly inconsistent, with only one entry shared between the TSB and BITRA. This suggests that ‘sports interpreting’ is not (yet) an established keyword in translation and interpreting studies. Searches in comprehensive general databases yielded even more limited results. Moreover, the degree to which the publications under review are relevant to the topic of sports interpreting varies considerably. Hence the plea for giving greater attention to empirical research done for Master’s theses, as exemplified in Section 4. Often driven by MA students’ personal interests and active involvement, such studies can involve fieldwork methods such as participant observation and ethnographic interviews and yield valuable insights into the perceptions and experiences of sports interpreters and relevant stakeholders.

Given the small and widely dispersed body of literature, the present mapping effort was undertaken as a scoping review to identify types of existing research and point to gaps in the current knowledge base. In particular, a discussion with regard to settings has shown that sports interpreting extends across the continuum from highly professional simultaneous conference interpreting to language assistance for migrant athletes by untrained volunteers, with media interpreting (of various kinds) as an important intermediate domain. Even the basic distinction between sporting and reporting reveals the notion of ‘sports settings’ as rather vague and in need of specification. Sports interpreting is done in a variety of settings, often with a focus on high-profile cases, serving different communicative needs in a wide array of organisational frameworks (FIFA, Olympics, Formula 1, etc.) and scenarios of interaction.

Thanks to audio-visual material being readily available and accessible, much attention has been given to highly mediatised international sports events and the press conferences and interviews associated with them. In contrast, the communication and interpreting needs of individual stakeholders, shaped to a large extent by institutional language and translation policies (or the lack thereof), have remained underexplored. Fieldwork, including auto-ethnography, and survey research methods are needed to fill these gaps, in combination with efforts to extend the range of sports under study. In this sense, evening the score, as proposed in my title, can be understood in at least two ways: (1) for sports interpreting in general, there is a need to catch up on studies of multilingual practices in a field of great social importance; and (2) with regard to the focus of research, attention should be extended beyond top stars and high-level professionals towards less visible sports and athletes, such as deaf sports and Paralympic Games. For media settings, this includes further engagement with interpreting done by para-professionals, that is, TV journalists with subject-matter expertise practising simultaneous interpreting.

Overall, sports interpreting is presented here not so much as a profession, and not (only) as a particular professional specialisation, but as a paradigm case of interpreting: It encapsulates nearly all the features that are relevant to the conceptualisation and study of interpreting in general: the range of international to intra-social settings, the varying levels of professionalism in practising interpreting, the use of different interpreting modes and linguistic modalities as well as novel forms of technology-enabled interpreting.

In the present review, the use of digital technologies in sports interpreting was exemplified only by video-mediated remote simultaneous interpreting. Given the rapid development of AI-powered digital tools, future studies, in press conferences and other settings, are likely to involve also services such as live captioning (i.e., speech to text) or even automatic speech-to-speech translation in conference-like as well as dialogue settings. Thus, sports interpreting as a presently underexplored area of study is likely to attract increased scholarly attention and more systematic research in the future, for which the present mapping of the field can hopefully serve as a foundation.

References

Albl-Mikasa, M., & Tiselius, E. (Eds.) (2022). The Routledge handbook of conference interpreting. Routledge.

* Alonso Araguás, I., & Zapatero Santos, P. (2019). La interpretación en competiciones de fútbol internacionales. Un estudio de caso: la UEFA. Sendebar, 30, 245–271.

* Antonini, R., & Bucaria, C. (2016). NPIT in the media: An overview of the field and main issues. In R. Antonini & C. Bucaria (Eds.), Non-professional interpreting and translation in the media (pp. 7–20). Peter Lang.

Axisa, M. (2024). Shohei Ohtani interpreter scandal: Money allegedly stolen was funneled through casinos. https://www.cbssports.com/mlb/news/shohei-ohtani-interpreter-scandal-money-allegedly-stolen-was-funneled-through-casinos-per-report/ (accessed 22.11.2024).

* Baines, R. (2012). The journalist, the translator, the player and his agent: Games of (mis)representation and (mis)translation in British media reports about non-anglophone football players. In R. Wilson & B. Maher (Eds.), Words, images and performances in translation (pp. 100–118). Bloomsbury.

* Baines, R. (2013). Translation, globalization and the elite migrant athlete. The Translator, 19(2), 207–228.

* Baines, R. (2018). Translation and interpreting for the media in the English Premier League. In S. Baumgarten & J. Cornellà-Detrell (Eds.), Translation and global spaces of power (pp. 179–193). Multilingual Matters.

Baker, M., & Saldanha, G. (Eds.) (2020). Routledge encyclopedia of translation studies. Third edition. Routledge.

* Bulut, A. (2016). Sports interpreting and favouritism: Manipulators or scapegoats? RumeliDE Journal of Language and Literature Studies, 6 (Special issue 2), 1–14.

Butterworth, M. L. (Ed.) (2021). Communication and sport. De Gruyter.

Cronin, M. (2014). Sport: A very short introduction. Oxford University Press.

Crowther, N. B. (2007). Sport in Ancient times. Praeger.

Declercq, C., & van Egdom, G.-W. (2024). Call for papers for a special issue: Sport(s) translation / translating sport(s). https://www.jostrans.org/about/cfp45 (accessed 22.11.2024).

* Demiray Akbulut, F., & Saba, H. K. (2023). An overview of football interpreting in Turkey and interpreters’ views. Turkish Journal of Sport and Exercise, 25(2), 175–180.

Diriker, E. (2003). Simultaneous conference interpreting in the Turkish printed and electronic media 1988-2003. The Interpreters’ Newsletter, 12, 231–243.

* Eftekhar, E., Ferdowsi, S., & Baniasad Azad, S. (2024). Exploring expectations of Iranian audiences in terms of consecutive interpreting: A reception study. Cadernos de Tradução, 44(1), e96718, 1–30.

* Falbo, C. (2022). Media conference interpreting. In M. Albl-Mikasa & E. Tiselius (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of conference interpreting (pp. 90–103). Routledge.

Fiorito, A. (2017). Sprecherwechsel beim Simultandolmetschen von Formel 1-Interviews. Master’s thesis, University of Vienna.

Gambier, Y., & van Doorslaer, L. (Eds.) (2021). Translation studies bibliography. Benjamins.

Gavioli, L., & Wadensjö, C. (Eds.) (2023). The Routledge handbook of public service interpreting. Routledge.

* Geens, R. (2009). Live subtitling through respeaking: A new discipline in interpretation? In I. Kemble (Ed.), The changing face of translation (pp. 100–109). University of Portsmouth.

* Ghignoli, A., & Torres Díaz, M. G. (2016). Interpreting performed by professionals of other fields: The case of sports commentators. In R. Antonini & C. Bucaria (Eds.), Non-professional interpreting and translation in the media (pp. 193–210). Peter Lang.

* Giera, I., Giorgianni, E., Lavric, E., Pisek, G., Skinner, A., & Stadler, W. (2008). The globalized football team: A research project on multilingual communication. In E. Lavric, G. Pisek, A. Skinner & W. Stadler (Eds.), The linguistics of football (pp. 375–390). Gunter Narr.

Giulianotti, R., & Robertson, R. (Eds.) (2007). Globalization and sport. Blackwell.

Grbić, N. (2015). Settings. In F. Pöchhacker (Ed.), Routledge encyclopedia of interpreting studies (pp. 370–371). Routledge.

* Harris, B. (2017). Unprofessional translation: A blog-based overview. In R. Antonini, L. Cirillo, L. Rossato & I. Torresi (Eds.), Non-professional interpreting and translation: State of the art and future of an emerging field of research (pp. 29– 43). John Benjamins.

* Itaya, H. (2021). The sports interpreter’s role and interpreting strategies: A case study of Japanese professional baseball interpreters. In M. L. Butterworth (Ed.), Communication and sport (pp. 137–159). De Gruyter.

* Jiménez Serrano, Ó. (2011). Backstage conditions and interpreter’s performance in live television interpreting: Quality, visibility and exposure. The Interpreters’ Newsletter, 16, 115–136.

Kootz, T. (2014). Dolmetschen im Sport. Eine empirisch gestützte Bestandsaufnahme. Master’s thesis, University of Leipzig.

Kraudinger, V. (2024). Strategien beim Simultandolmetschen von Formel 1-Interviews im ORF. Master’s thesis, University of Vienna.

* Lavric, E., & Steiner, J. (2012). Football: le défi de la diversité linguistique. Bulletin Suisse de Linguistique Appliquée (VALS-ASLA), 95, 15–33.

Lavric, E., & Steiner, J. (2017). Personal assistants, community interpreting, and other communication strategies in multilingual (European) football teams. In D. Caldwell, J. Walsh, E. Vine, & J. Joureidini (Eds.), The discourse of sport: Analyses from social linguistics (pp. 56–70). Routledge.

* Locker McKee, R., & Napier, J. (2002). Interpreting into International Sign Pidgin: An analysis. Sign Language & Linguistics, 5(1), 27–54.

* Lorca Antón, J. A. (2015). Interpretación deportiva: Estudio sobre el mercado laboral en España. Master’s thesis, University of Alicante.

* Maselli, S. (2013). Interpretare il calcio. Analisi di conferenze stampa mediate da interprete per la presentazione di nuovi acquisti: un approccio interazionale. Master’s thesis, Uiversità degli Studi Internazionali di Roma (UNINT).

Mikkelson, H., & Jourdenais, R. (Eds.) (2015). The Routledge handbook of interpreting. Routledge.

Müllebner, T. (2017). Dolmetschen bei den Special Olympics Worlds Winter Games 2017. Eine Settinganalyse. Master’s thesis, University of Vienna.

Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18:143, 1–7.

Nußbaum, D. (2018). Dolmetschen bei Formel-1-Übertragungen des ORF. Master’s thesis, University of Vienna.

* Okyayuz, A. ş., & Erkazanci Durmuş, H. (2022). Deaf sports and identity formation: A pilot project proposal for the training of sign language interpreters for deaf sports. In S. Sancaktaroğlu-Bozkurt & T. E. Taşdan-Doğan (Eds.), Translation studies: Translating in the 21st century – multiple identities (pp. 19–40). Peter Lang.

Oreški, J. (2016). Der Status der DolmetscherInnen bei internationalen Sportveranstaltungen. Eine explorative Fallstudie im Feld einer Angelweltmeisterschaft. Master’s thesis, University of Graz.

Pfaller, C. (2020). Highspeed-Bedingungen: Dolmetschen an der Rennstrecke – eine Analyse des translatorischen Handelns bei Formel-1-Übertragungen im ORF und RTL. Master’s thesis, University of Vienna.

Pignataro, C. (2011). Skill-based and knowledge-based strategies in television interpreting. The Interpreters’ Newsletter 16, 81–98.

Pöchhacker, F. (2010). Media interpreting. In Y. Gambier & L. van Doorslaer (Eds.), Handbook of Translation Studies. Vol. 1 (pp. 224–226). John Benjamins.

Pöchhacker, F. (Ed.) (2015). Routledge encyclopedia of interpreting studies. Routledge.

Pöchhacker, F. (2022a). Interpreters and interpreting – shifting the balance? The Translator, 28(2), 148–161.

Pöchhacker, F. (2022b). Introducing interpreting studies. Third edition. Routledge.

* Sandrelli, A. (2012a). Interpreting football press conferences: The FOOTIE corpus. In C. J. Kellett Bidoli (Ed.), Interpreting across genres: Multiple research perspectives (pp. 78–101). E.U.T.

* Sandrelli, A. (2012b). Introducing FOOTIE (Football in Europe): Simultaneous interpreting at football press conferences. In F. Straniero Sergio & C. Falbo (Eds.), Breaking ground in corpus-based interpreting studies (pp. 119–153). Peter Lang.

* Sandrelli, A. (2015). “And maybe you can translate also what I say”: Interpreters in football press conferences. The Interpreters’ Newsletter, 20, 87–105.

* Sandrelli, A. (2017). Simultaneous dialogue interpreting: Coordinating interaction in interpreter-mediated football press conferences. Journal of Pragmatics 107, 178–194.

* Sandrelli, A. (2022). Conference interpreting at press conferences. In M. Albl-Mikasa & E. Tiselius (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of conference interpreting (pp. 80–89). Routledge.

Schmol, S. (2021). Mediendolmetschen im Leistungssport Tennis. Die Rolle der SportkommentatorInnen als DolmetscherInnen. Master’s thesis, University of Vienna.

* Seeber, K. G., Keller, L., Amos, R., & Hengl, S. (2019). Expectations vs. experience: Attitudes towards video remote conference interpreting. Interpreting, 19(2), 270–304.

* Straniero Sergio, F. (2003). Norms and quality in media interpreting: The case of Formula One press conferences. The Interpreters’ Newsletter 12, 135–165.

* Suarez Lovelle, G. (2024). Interpretación simultánea en las ruedas de prensa de la EURO 2020: Estudio sobre las estrategias de formulación de pregunta y respuesta. inTRAlinea, 26, 2654, 1–14.

* Uyanık, G. B. (2017). Translation and interpreting in sports contexts. In A. Angı (Ed.), Translating and interpreting specific fields: Current practices in Turkey (pp. 101–114). Peter Lang.

* Wang, L., & Zhang, J. (2011). Community interpreting in China since the Beijing Olympics 2008 – Moving towards a new Olympic discipline? In C. Kainz, E. Prunč & R. Schögler (Eds.), Modelling the field of community interpreting: Questions of methodology in research and training (pp. 263–279). LIT-Verlag.

Wolfbauer, C. (2018). Delegation Liaison Assistants (DAL) als TranslatorInnen? Fallstudie zur interkulturellen Kommunikation bei den Special Olympics World Winter Games 2017 in Österreich. Master’s thesis, University of Graz.

* https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8618-4060; email: franz.poechhacker@univie.ac.at↩︎