Gender-Inclusive Translations Put to the Test: Measuring Performance of Quadball Referee Certification Test Takers

Joke Daems 1, Ghent University & International Quadball Association

ABSTRACT

This study tests the impact of gender-inclusive language in a real-life, timed scenario, in collaboration with the International Quadball Association (IQA). This article describes the textual impact of the inclusive translation strategies currently in use at the IQA for different languages (French, German, Italian, Spanish) and explores the time and success rate of quadball referee certification test takers taking the official assistant referee tests in the original English and in translation. For French, Italian, and Spanish, an additional comparison is made between a masculine and inclusive variant. Results show that, while inclusive strategies impact up to 21% of the text, this has no measurable effect on the time needed to take a test or on the final score obtained. However, test takers taking the English referee tests were found to score higher than those taking the tests in translation, with the exception of German.

KEYWORDS

Gender-inclusive language, quadball, referee tests, sports translation, readability, comprehensibility

Introduction

Quadball, a mixed-gender, full-contact sport played since 2005, has expanded to over 40 countries worldwide. The international rules governing the sport are determined by the International Quadball Association (IQA). IQA members are National Governing Bodies (NGBs), which usually represent countries recognised by the International Olympic Committee or the Global Association of International Sports Federations, but in some cases can be nations without official recognition, such as Catalonia, represented in quadball by the Associació de Quadbol de Catalunya. This is due to the interest in international quadball competitions in the region originating in Barcelona before broader uptake in Spain, leading to the creation of a Catalan NGB before a Spanish NGB was in place. The IQA website1 currently mentions 34 member NGBs (eighteen in Europe, six in Asia, four in South America, three in North America, two in Oceania, and one in Africa) and eight areas of interest (three in Asia, three in Africa, one in Europe, and one in South America). Based on the most recent membership analysis published in 20232, quadball was most popular in the US (with 87 teams and 1690 players), followed by Germany (53 teams, 1280 players), the UK (38 teams, 570 players), Canada (27 teams, 550 players), Türkiye (eighteen teams, 400 players), and Australia (34 teams, 300 players). Administratively, the IQA is a US non-profit (the organisation is exploring whether it should remain incorporated in the US given the current political climate), but in practice, it consists of volunteers working all around the world. Due to its origin and popularity in English-speaking countries and its global nature, the working language at the IQA is English.

A quadball team consists of up to 21 players, with six to seven players on pitch at the same time: six players during the first twenty minutes of game time (the “seeker floor”) and seven from the twentieth minute onwards. Teams are ‘mixed-gender’, which explicitly includes people of all genders, as evidenced in the rulebook: “All quadball athletes have the right to define how they identify and it is this stated gender that is recognized on pitch” (IQA, 2024, p. 6). This element of gender inclusivity is crucial for many athletes, particularly for trans and non-binary athletes whose sense of belonging is often challenged in other sports (Greey, 2023; Zanin et al., 2023). The presence of multiple genders on pitch is additionally enforced in the rulebook under the ‘gender maximum rule’ (IQA, 2024, p. 11). The broader quadball community’s support for gender inclusivity is demonstrated by the evolution of this rule: in the 2022 rulebook, a maximum of four athletes of the same gender could be on pitch at the same time, in the 2024 rulebook, this maximum was lowered to three athletes, based on community feedback (IQA, 2023).

Given that the use of the ‘generic’ masculine in writing has been shown to elicit male bias in readers’ minds (Stahlberg et al., 2007) and that gender-inclusive language can be used to reduce stereotyping and discrimination (Koeser et al., 2015; Sczesny et al., 2016; Tibblin et al., 2023), the IQA’s Communication Department encourages its members to use gender-inclusive language. For the main working language, English, inclusive language has been the norm since at least the 2014 rulebook3. Inclusivity is achieved by avoiding gender-specific nouns and using they/them pronouns throughout. For languages the IQA translates into, however, this is not as straightforward. While IQA translators are encouraged to use gender-inclusive language whenever possible, translators sometimes choose different strategies, depending on the language and the context (Daems, 2023).

A specific context is that of the online referee (re)certification tests, for which the IQA is also responsible. Due to the complexity of the sport, a quadball game needs to have at least six referees (IQA, 2024, p. 108). For official games, only people with valid referee certifications for the current rulebook can act as referees. Referee certification tests are taken under time pressure, which means that the readability and comprehensibility of the tests is particularly important. In the past, IQA translators have sometimes decided against using inclusive language for certification tests to ensure readability (Daems, 2023). While the supposedly negative impact of inclusive language on readability and comprehensibility is indeed an argument used by opponents of inclusive language (Manesse, 2022), this has rarely been tested empirically.

In 2023, the IQA conducted a small pilot study for German, with a dummy test containing a selection of fourteen questions of the official 2022 referee test. Contrary to expectations, test takers in the inclusive condition were actually found to be faster and score higher than test takers in a masculine condition (Daems, 2024). While exploratory, the results encouraged the IQA directors to run a similar experiment at a larger scale, this time using the real 2024 certification tests. The present article reports on this larger experiment. When taking the certification tests for the 2024 rulebook via the official IQA Referee Hub website, test takers could choose between English, French, Italian, Spanish, and German. Participants taking the test in French, Italian, or Spanish were exposed to the test in either the inclusive variant, or a (newly created) masculine variant.

This study provides an answer to the following overarching research question: How do (translation) strategies and language variations impact referee tests (length, readability) and test taker performance (speed, success rate) across different languages?

The following section reviews research on gender-inclusive language for four IQA languages, their societal acceptance, and readability. The article then covers the translation process, methodology, and findings, very likely marking the first empirical study of such language in a high-stakes context in sports.

2. Related research

2.1. Reading speed

Before factoring in how gender-inclusive language strategies might influence readability, we need to understand what ‘average’ reading looks like for different languages. A meta-analysis of reading rate revealed that, for English, the average reading rate is 238 words per minute for non-fiction (Brysbaert, 2019), at least for native speakers. L2 speakers of English need around 10% more time to read a text (Dirix et al., 2020). Reading rates for languages relevant to the present study are 214 words per minute for French, 260 words per minute for German, 285 words per minute for Italian, and 278 words per minute for Spanish (Brysbaert, 2019). The author also included an ‘expansion index’, which shows how many words are needed in a language to express the same ideas as an English text of 1,000 words: 1,062 for French, 975 for German, 1,006 for Italian, and 1,025 for Spanish (Brysbaert, 2019). Combining that information, we can extrapolate that the average reader would need 4.2 minutes to read a 1,000-word text in English. Someone reading the text in translation would need 4.96 minutes when reading in French, 3.75 minutes when reading in German, 3.52 minutes when reading in Italian, and 3.69 minutes when reading in Spanish. Other factors that influence reading speed are the average word length in a text as well as word frequency (Kuperman et al., 2024). As will be detailed below, some inclusive language strategies might increase average word length or have an impact on the expansion rate, as they take more words to express the same ideas, whereas other strategies are less likely to impact word or text length.

2.2 Gender-inclusive language strategies

While genderless languages (e.g., Finnish, Turkish) only express gender lexically in some nouns (e.g. ‘man’ versus ‘woman’) and natural gender languages (e.g., English, Swedish) additionally mark gender via pronouns (e.g., ‘she’ or ‘he’), translators need to decide on specific strategies when working into grammatically gendered languages (e.g., French, German, Italian or Spanish), where gender is marked in different parts of speech. Originally driven by the need for feminisation, inclusive language strategies have more recently come to encompass non-binary identities as well (Abbou, 2024; Meuleneers, 2024). These strategies can include avoiding gender by using collective words and generalisations (‘indirect non-binary language’ according to the typology suggested by López (2022)) or the use of typographical characters and gender-inclusive morphemes and pronouns (‘direct non-binary language’, ibid.). Typographical characters are generally introduced between the masculine base of a word and a feminine suffix (Girard et al., 2022). For French, the interpunct or point median seems to be the most commonly used in practice today, e.g., instead of using the masculine form joueur (player) or writing the masculine and feminine forms in full (joueur ou joueuse), a so-called ‘abridged doublet’ form is used: joueur·euse, which is a combined form of the masculine joueur and the feminine ending -euse, joined by the interpunct. Similarly, German has the Gendersternchen (‘gender star’ or asterisk, *), or the Gender-Doppelpunkt (‘gender colon’). The latter is the strategy perceived as most readable and comprehensible by translators (Paolucci et al., 2023). The most actively used strategy for Italian at the time of writing is the schwa (-ə) as the gender-inclusive morpheme (Gheno, 2024). Common strategies for Spanish include the use of the letters ‘e’ and ‘x’ where the usual gender-marked ‘a’ or ‘o’ would be. Of these, the ’e’ seems to have the greatest chance at being publicly accepted and adopted (Papadopoulos, 2022).

The introduction of gender-inclusive language strategies has not been without controversy. It is often driven by activists and younger, politically left-leaning people to improve gender equality in society (Meuleneers, 2024; Nodari, 2024; Sauteur et al., 2023; Slemp et al., 2020; Vecchiato, 2025). Gender-inclusive language indeed reduces the stereotypical gender associations evoked by role nouns (Abbondanza et al., 2025; Stetie & Zunino, 2024). Compared to pair forms (writing both masculine and feminine versions of a word in full), inclusive neutralisation strategies such as the schwa are perceived as more warm and competent, although the results depend on the type of text and the person reading it (Nodari, 2024). Formal language institutions, however, actively oppose inclusive language and claim it will tarnish the language itself (Coady, 2024; De Santis, 2022; Fiorentini & Oggionni, 2024; Gunther, 2022; Johnson, 2024; Papadopoulos, 2022; Pecorari & Ferrari, 2024; Pfalzgraf, 2024). A key argument that is raised against inclusive language is the idea that it is much harder to read and understand (De Santis, 2022; Johnson, 2024; Rock, 2021; Schneider, 2020), especially for those with cognitive disabilities. For languages with different potential strategies (e.g., using pair forms, avoiding gendered expressions, using different typographical characters or neomorphemes), choosing a strategy that maintains readability and comprehensibility is therefore not always straightforward for a translator (Burtscher et al., 2022; Daems, 2023).

2.3. Readability and comprehensibility of gender-inclusive strategies

The rare empirical evidence on comprehensibility and readability is inconclusive and suggests that people get used to inclusive language as they encounter it more frequently. Comparing the readability of masculine language with gender-inclusive strategies, most researchers found that inclusive language was not harder to read (Girard et al., 2022; Liénardy et al., 2023; Stetie & Zunino, 2022). A self-paced reading experiment did show that participants were slower to read an inclusive text compared to a masculine text, although this effect got smaller throughout the experiment (Zami & Hemforth, 2024). With regards to comprehensibility, most studies show no negative impact of inclusive language compared to masculine language (Friedrich et al., 2021, 2022; Pabst & Kollmayer, 2023), although perceived comprehensibility was sometimes lower (di Carlo, 2024; Liénardy et al., 2023), and singular forms impaired comprehensibility more than plural forms (Friedrich et al., 2021). Participants in the study by Zami & Hemforth (2024) also made a few more errors when answering comprehension questions about the text they read, but these effects were not found to be statistically significant.

What existing studies have in common, however, is that they examine comprehensibility and readability in artificial, controlled experimental settings, which makes it difficult to apply their findings directly to real-life situations. Some researchers argue that gender-inclusive language is likely to have limited impact on readability in real-world settings, given that it affects less than one percent of words in German press texts (Müller-Spitzer et al., 2024). To the best of the author’s knowledge, this is the first time gender-inclusive language has been empirically put to the test in a real-life scenario.

3. IQA referee tests & translation workflow

A new IQA rulebook is released in English every two years. Each update introduces changes based on community feedback and proposals from the Rules Team. The first IQA rulebook was derived from the US Quidditch Rulebook, written by English native speakers from the US. Historically, the IQA rules team manager has been from the US (although the current manager is German). Any updates to the rulebook are always reviewed by English native speakers before publication. Referees need to be certified for the current rulebook before they can be assigned to official games. In 2023, 30% of all quadball players (2336 out of 7870) had obtained at least one level of certification for the 2022 rulebook. Referees who obtained certification for previous rulebooks get the chance to take recertification tests. New referees have to take the regular ‘initial’ certification tests. The latest version of the rulebook at the time of writing was published in August 2024. The corresponding referee (re)certification tests were gradually made available in English in the following months.

The referee certification tests can be taken online at any time via the IQA Referee Hub4. In total, there are seven different referee tests: one for the time/scorekeeper and two tests (an initial test and a recertification test) for each of the three types of referee (flag referee - FR, assistant referee - AR, and head referee - HR). In order to be able to take the HR test, a person first needs to have obtained the other certifications. Tests consist of multiple-choice questions with four potential answers, with only one correct answer. For all initial tests, a score of 80% or more is needed in order to pass and obtain the certification. If a test taker fails, they can try again after 24 hours (72 for the HR test), with a max of six attempts per test.

The IQA translation team consists entirely of unpaid volunteers, with fluctuating availability. In 2023, the IQA had translators working into eight different languages, with two (Catalan) to six (German) translators for each language (Daems, 2023). At the time of release of the 2024 referee tests, however, the IQA only had one or two translators for each language, and the number of languages was reduced to five (Catalan, French, German, Italian, and Spanish). Languages are selected on the basis of volunteer availability, not for strategic or political reasons. All translation volunteers are native speakers of the language they translate into and are highly proficient in English. Some of the translators have been members of the team since 2020, others join on a temporary basis. Volunteers are usually (ex-)players who are very familiar with the sport and its terminology, but most of them do not have a translation background. Most translation teams translate the rulebook (a 30,000-word document) first. If they have the capacity, they also translate (some of) the referee tests. For each test, the IQA has a database of potential multiple-choice questions, of which a random selection is presented to test takers whenever they start a new test. Combined, the tests consist of almost 30,000 words to be translated. Translators work in the online CAT tool Matecat, with the support of a translation memory, but without machine translation, as this was shown not to be a viable option for this kind of translation work due to the specificity of quadball terminology and the gender-inclusive strategies used (Daems, 2024). Before publication, translated documents are first revised and then proofread by another IQA translator or by a member of the quadball community with the relevant linguistic expertise. Translators are instructed to use inclusive language. The current strategies for the different languages in the IQA are largely similar to those discussed in previous work on IQA translation strategies (Daems, 2023). For French, the interpunct is used between the masculine basis and feminine endings of a word, and the non-binary pronoun iel is used where the English uses they. The German translation team currently uses the colon as the non-binary marker. While the rulebook translation for German contains gender-inclusive forms throughout, the translation strategy for the German referee tests depends on the kind of question (Daems, 2023): More general questions include gender-inclusive articles (der:die), but for specific situations that happen in a game, the translations rotate between different gendered forms to improve readability (e.g., ‘die Haupt-Referee’ in one question, ‘der Haupt-Referee’ in another). For Italian, IQA translators have historically been reluctant to use the inclusive ending ‘-ə’, only using it in the introductory chapters of the rulebook and in smaller documents (Daems, 2023). For the translation of the 2024 referee tests and rulebook, however, the current IQA translator decided to use the inclusive ending throughout. For Spanish, the gender-inclusive ending ‘-e’ is used.

4. Methodology

For the 2024 referee (re)certification test translation, the IQA Translation Manager informed translators via the official IQA Volunteers Slack channel that the study aimed to understand how language use impacts test timing and results across English and other languages, comparing gender-inclusive and masculine language, with the goal of better addressing community language needs, not replacing inclusive language. For example, if it would become clear that people taking the test in another language or in an inclusive condition need more time, the referee test timing for future tests could be adapted accordingly, or community resources on gender-inclusive language could be provided to make people more familiar with the language. Translators were asked if they would be willing to participate by creating two different versions of the referee tests (the usual inclusive version as well as a masculine version) and were told to keep the setup a secret for their respective communities, as the goal was to measure people’s actual, unbiased results. The Catalan translator chose not to participate, as the (small) number of potential referees in the Catalan quadball community is proficient enough to take the tests in English. The German translators only had the capacity to make their usual translation of the referee test (using a combination of inclusive and gendered language forms described above). Translators for French, Italian, and Spanish agreed to make two versions of the referee tests.

Translators were instructed to first make their usual, inclusive translation in Matecat. They then received access to a Google Sheet with two tabs: one with their inclusive translation, and one with the same translation that they then manually edited to create a masculine version, so as to not affect the translation memory. An overview of the different strategies used in this study can be seen in Table 1.

| Language | Default inclusive IQA variant | Masculine variant |

|---|---|---|

| English | Green chaser starts the game on the starting line in the Purple half of the field. As sticks up is called, they run across the starting runner zone to try and defend which accidently blocks Purple beater from getting possession of the dodgeball. What is your call? | n/a |

| French | Un·e poursuiveur·euse Vert·e commence le match sur la ligne de départ dans la moitié de terrain Violette. Lorsque le départ est lancé, iel court à travers la zone de départ initiale pour tenter de défendre et empêche accidentellement un·e batteur·euse Violet·te de récupérer son dodgeball. Quelle est votre décision ? | Un poursuiveur Vert commence le match sur la ligne de départ dans la moitié de terrain violette. Lorsque le départ est lancé, il court à travers la zone de départ initiale pour tenter de défendre et empêche accidentellement un batteur Violet de récupérer son dodgeball. Quelle est votre décision ? |

| Italian | Lə cacciatorə verde inizia il gioco sulla linea di partenza nella metà campo della squadra viola. Appena viene chiamato lo "sticks up", lə giocatorə corre oltre la linea di partenza dei corridori per cercare di difendere, e incidentalmente impedisce allə battitorə viola di prendere il possesso della dodgeball. Qual è la tua chiamata? | Il cacciatore verde inizia il gioco sulla linea di partenza nella metà campo della squadra viola. Appena viene chiamato lo "sticks up", Il giocatore corre oltre la linea di partenza dei corridori per cercare di difendere, e incidentalmente impedisce al battitore viola di prendere il possesso della dodgeball. Qual è la tua chiamata? |

| Spanish | Le Cazadore verde comienza el juego en la línea de inicio en la mitad morada del campo. Cuando se llama "bastones arriba", corren a través de la zona de corredores de inicio para intentar defender, lo que accidentalmente bloquea al golpeadore morade de obtener la posesión de la pelota de dodgeball. ¿Cuál es tu decisión? | El Cazador verde comienza el juego en la línea de inicio en la mitad morada del campo. Cuando se llama "bastones arriba", corren a través de la zona de corredores de inicio para intentar defender, lo que accidentalmente bloquea al golpeador morado de obtener la posesión de la pelota de dodgeball. ¿Cuál es tu decisión? |

| German | Grüner Chaser startet das Spiel an der Start-Seitenlinie in der Hälfte von Team Lila. Als "Sticks up" ertönt, rennt er durch die Start-Läufer:innen-Zone um zu verteidigen und blockiert dabei aus Versehen Lila Beater davor den Dodgeball in Besitz zu nehmen. Wie entscheidest du? | n/a |

Table 1. Example question from the AR initial referee certification test showing the different translation strategies for each IQA working language and the masculine variants created for this study

4.1. Data collection

To not overwhelm volunteers, translators were asked to focus on the ‘masculinisation’ of the AR initial test for this study, as this is the test that is taken the most. Tests were made available via the official IQA Referee Hub. For German, only the usual variant with a mix of strategies was made available. For French, Italian, and Spanish, test takers were randomly assigned to either the inclusive or masculine condition and this condition remained the same for all test attempts (e.g., if someone needed three attempts to pass the AR initial test, they would see all three attempts in either the inclusive or masculine condition, not a mix). They were not informed about the fact that two versions were available, either before or after taking the test. Data collection started at different times for the different languages, as translations gradually became available. Collection started on 30 October 2024 for English, 19 November 2024 for French, 10 February 2025 for Spanish, 17 February 2025 for Italian, and 5 May 2025 for German. Data were collected until 15 June 2025.

During this time period, there were 884 certification attempts for English, 129 for French (61 inclusive, 68 masculine), 14 for Spanish (5 inclusive, 9 masculine), 43 for Italian (19 inclusive, 24 masculine), and 24 for German. Test takers can have multiple attempts at taking the same test (max 6). Considering only the first certification attempt for each test taker, data were collected from 582 unique test takers for English, 62 for French (31 taking the test in the inclusive condition, 31 in the masculine), 7 for Spanish (3 inclusive, 4 masculine), 15 for Italian (8 inclusive, 7 masculine), and 17 for German. The English test was taken by members from 24 different NGBs. NGBs with more than ten test takers who took the English test were Germany (254), United Kingdom (77), Spain (50), Türkiye (35), Belgium (24), Austria (19), Norway (18), Poland (16), Italy (14), France (14), and Czechia (10). The French test was taken mostly by members from France (56), some from Belgium (3), and one each from Catalonia, Germany, and the UK. The Spanish test was taken by members from Spain (3), Argentina (2), Brazil (1), and Mexico (1). The Italian test was only taken by members from the Italian NGB. The German test was taken by members from Germany (15), Austria (1), and Czechia (1).

4.2. Translation analysis

Given that earlier work suggested that not many words would actually be impacted by introducing inclusive language for German (Müller-Spitzer et al., 2024), the number of gender-inclusive language characters in the IQA translations was counted (interpunct for French, colon for German, schwa for Italian). For Spanish, the online Diffchecker5 tool was used to count the number of words that had been changed between the masculine variant and the inclusive variant.

Microsoft Excel was used to compare the text length (in characters and words) of the different translations. The ‘LEN’ function was used to determine the length in characters of each referee test question in each language and variant and a formula was used to calculate the number of words.

To test if the different variants were indeed significantly different from one another with regards to text length and average word length, a one-way ANOVA was conducted with post-hoc Tukey HSD Test6 to identify the actual differences between specific languages and conditions: English was compared to each of the different language variants, and for French, Italian, and Spanish, the inclusive variant was compared to the masculine variant.

4.3. Certification test analysis

Data were extracted from Referee Hub in csv-format. For each test attempt, the file contains a user id, the test language, their NGB, a start time, the duration (time limit of 30 minutes), the final score, and the variant ( ‘inclusive’ or ‘masculine’).

To study performance, first a global analysis was performed on the entire dataset, in the form of two-sample t-tests in Microsoft Excel to check if there were significant differences between English and translations for test duration and final score. An additional analysis was conducted to check for differences between English and specific languages, and for differences between conditions (inclusive versus masculine) for French, Italian, and Spanish. Since the same test taker could take a test multiple times, an analysis was made of overall success rate (how many test takers managed to pass the test eventually) and the average number of tests needed to pass. To reduce the impact of individual test takers on results, the analysis was repeated on a subset of the data, only taking into account each test taker’s first attempt.

5. Results

5.1. Impact of language and translation strategy on text and word length

Table 2 shows differences in text length across languages (for reference, the English text was 6296 words long) and indicates how many words were impacted by the inclusive-language strategies currently in use at the IQA.

| Language | Text length masculine version (words) | Text length inclusive version (words) | Words affected by inclusive strategy | % of words affected by inclusive strategy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| French | 7505 | 7561 | 1567 | 21 |

| German | 5860 | 86 | 1.5 | |

| Italian | 7159 | 7208 | 1139 | 16 |

| Spanish | 7650 | 7652 | 1286 | 17 |

Table 2. Text length per language for the inclusive-language variants and the percentage of words impacted by inclusive-language strategies

The impact was greatest for French, with 21% of words impacted by inclusive strategies, and smallest for German, with only 1.5% of words impacted. As discussed, the German translators use a mix of gendered and gender-inclusive strategies, and they often avoid the need for inclusive strategies by retaining English position names, as is common in the sport (e.g., they use ‘Keeper-Zone’ rather than ‘Hüter:innen-Zone’). With the exception of German, which was only 93% of the English text length, all languages used more words than English (the expansion rate was 114% for Italian, 120% for French, and 122% for Spanish).

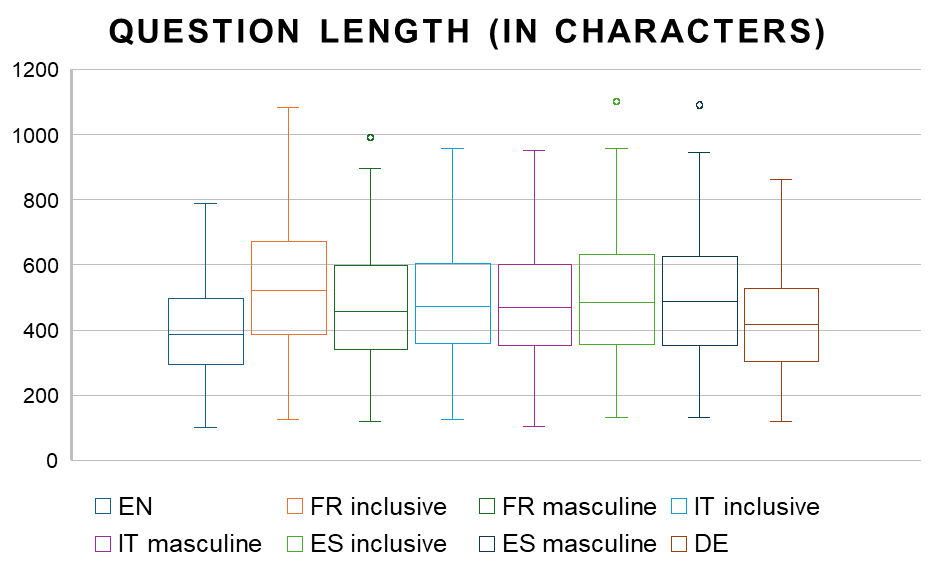

In addition to the overall word length of the entire document, the length of each test question across languages was compared as well. As can be seen in Figure 1, translations were longer (in characters) than the English source text. Of the different languages, German was closest in length to English. Differences between inclusive and masculine versions within languages were minimal, with the exception of French, where the inclusive variant was longer.

Figure 1. Distribution of question length (in characters) for all AR initial referee test questions for each language and condition

A one-way ANOVA revealed that there was a significant difference in question length between at least two language conditions (F(7, 688) = 4.48, p < 0.001). Post hoc comparisons using the Tukey HSD test indicated that there were significant differences in question length between English and inclusive French, and English and inclusive Spanish at p < 0.01, and between English and inclusive Italian, and English and masculine Spanish at p < 0.05. No significant differences were found between the masculine and inclusive versions of any language. The only other significant difference was between inclusive French and German at p < 0.01.

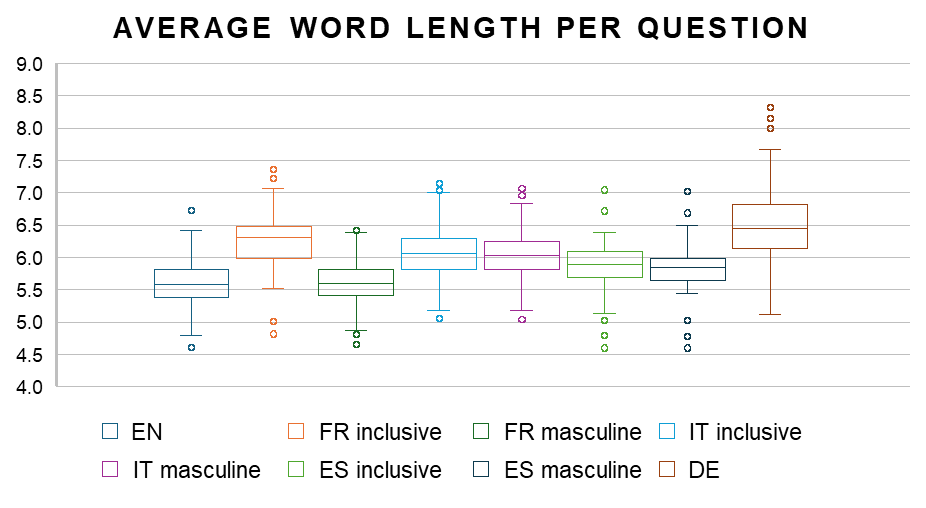

As reading research showed how average word length has an impact on reading rate (Kuperman et al., 2024), the average word length across the different conditions was also compared (Figure 2). While German seemed closest to English with regards to question length (Figure 1), the average word length (Figure 2) was much higher. French again seemed to be the language with the greatest differences between the inclusive and masculine variants.

Figure 2. Distribution of average word length for all AR initial referee test questions for each language and condition

A one-way ANOVA revealed that there was a significant difference in average word length between at least two language conditions (F(7, 688) = 46.33, p < 0.001). Post hoc comparisons using the Tukey HSD test indicated that there were significant differences in average word length between English and all language variants, with the exception of masculine French. These differences were significant at p < 0.01, with the exception of masculine Spanish, which was significantly different from English at p < 0.05. When looking at the results for the inclusive and masculine conditions within each language, only inclusive French was significantly different from masculine French at p < 0.01.

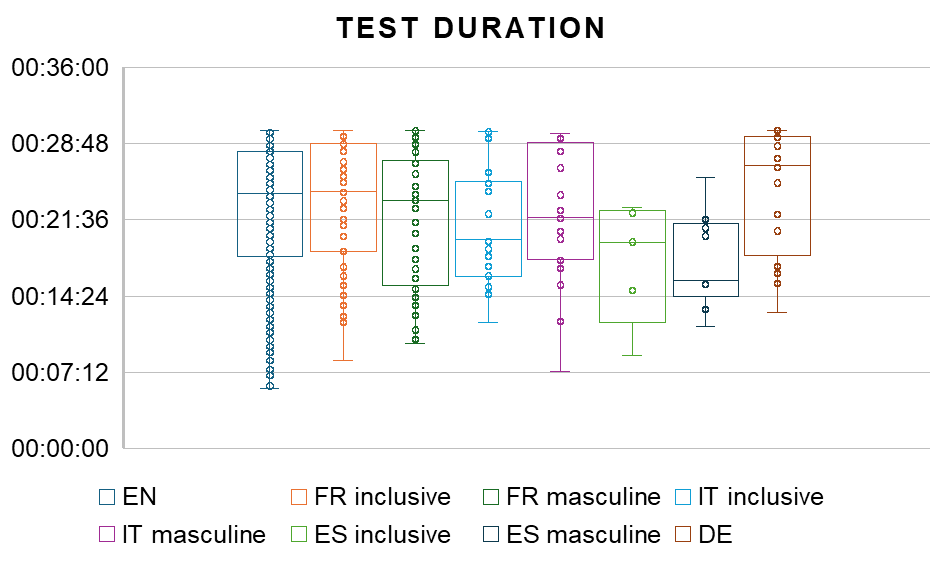

Impact of language and translation strategy on test duration

Figure 3 shows the distribution of test duration in each language and condition. Despite English having fewer characters per question and the shortest average word length, participants seemed to take more time to complete the test in English than in Italian or Spanish. A two-sample t-test comparing English to all translations combined, however, showed that test takers did not spend significantly more or less time on the translated tests (M=1330 seconds, SD=363) than on the English tests (M=1376, SD=356), t(311) = 1.166, p = 0.1.

Figure 3. Distribution of test duration for all AR initial referee test attempts across languages and conditions (for reference: max test duration = 30 minutes)

A two-sample t-test comparing English to French showed that test takers did not spend significantly less or more time on the French tests (M=1341 seconds, SD=367) than on the English tests (M=1376, SD=356), t(165) = 1.002, p = 0.32. Similar results were found for Italian, (M=1303, SD=345), t(46) = 1.34, p = 0.19, and German (M=1470, SD=330), t(24) = -1.35, p = 0.19. Participants taking the test in Spanish did seem to take significantly less time (M=1064, SD=278) than those taking the test in English, t(14) = 4, p < 0.05.

When looking at the impact of condition (masculine versus inclusive) on test duration for each language, there was no significant difference. An overview of the t-test results can be seen in Table 3.

| Language | Inclusive M (SD) | Masculine M (SD) | df | t-stat | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| French | 1389 (353) | 1299 (375) | 127 | 1.39 | 0.17 |

| Italian | 1274 (322) | 1326 (361) | 40 | -0.48 | 0.63 |

| Spanish | 1059 (313) | 1066 (257) | 7 | -0.04 | 0.97 |

Table 3. Two-sample t-test results comparing the test duration (in seconds) between the inclusive condition and masculine condition for each language

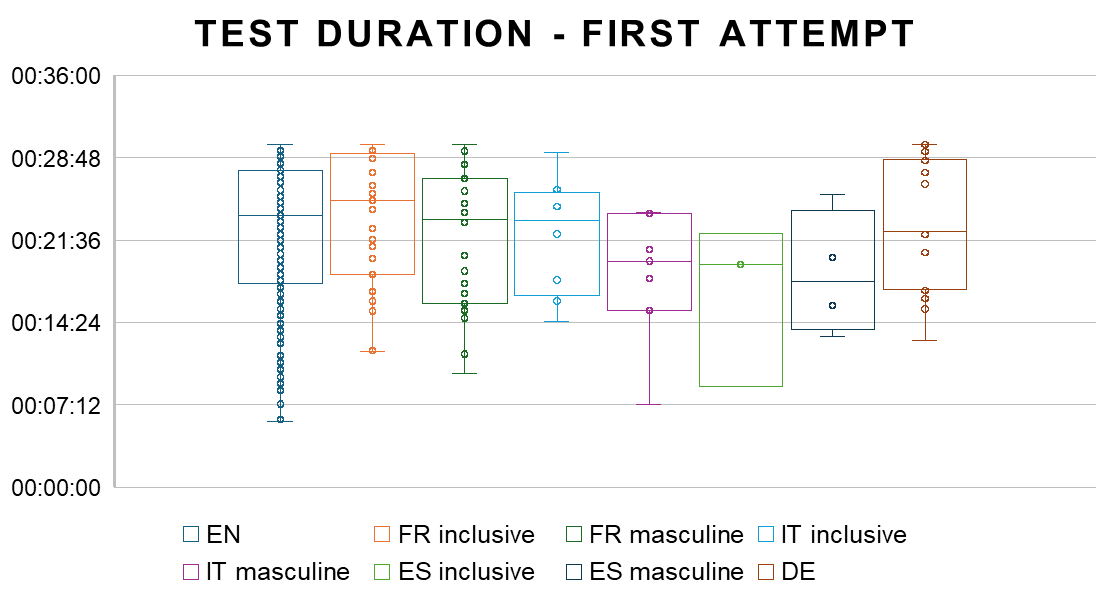

Limiting the analysis to only the first attempt of each test taker (Figure 4) changed these findings somewhat. There was no significant difference between the time needed to take the test in English (M=1354, SD=356) and in translation (M=1321, SD=352), t(138) = 0.85, p = 0.4), but the difference between English and Spanish (M=1073, SD=317) was no longer significant, with t(6) = 2.15, p = 0.08.

Figure 4. Distribution of test duration for the first test attempt per test taker across languages and conditions

5.3. Impact of language and translation strategy on test success

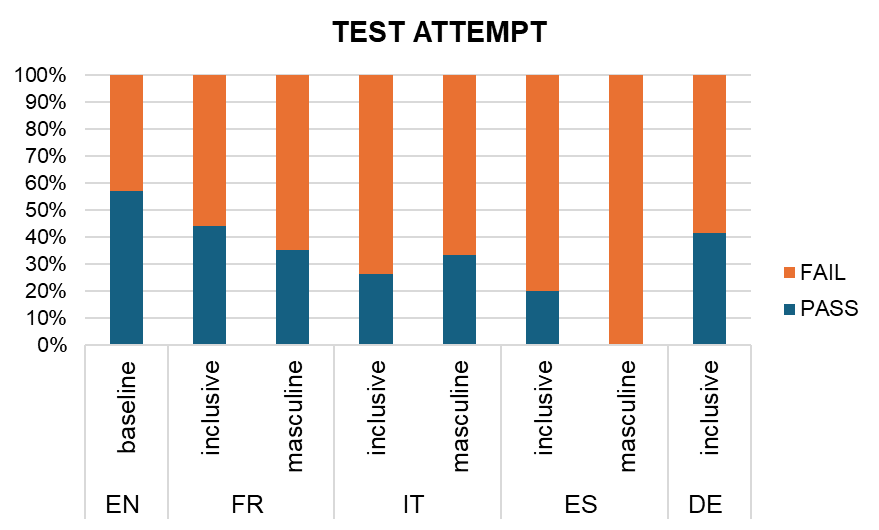

To determine test success, Figure 5 gives an indication of the pass/fail ratio across all test attempts. Compared to English, fewer of the translated tests were passed.

Figure 5. Overall percentage of passed (= test score of 80% or higher) test attempts per test variant

Since test takers can take a test multiple times (max 6 times), it was also necessary to check whether individual test taker success rate was different across conditions. For English, 85% of test takers eventually passed the test, needing 1.47 attempts on average to pass. Table 4 contains an overview of pass rate and attempts needed for the other languages and conditions.

| Condition | Pass rate | Attempts to pass | Test takers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inclusive French | 75% | 1.74 | 36 |

| Masculine French | 71% | 2.17 | 34 |

| Inclusive Italian | 50% | 2.6 | 10 |

| Masculine Italian | 89% | 2.25 | 9 |

| Inclusive Spanish | 25% | 1 | 4 |

| Masculine Spanish | 0% | n/a | 4 |

| German | 53% | 1.4 | 19 |

Table 4. Overview of pass rate (percentage of test takers that eventually passed the test), average number of attempts needed to pass the test, and total number of test takers for each condition

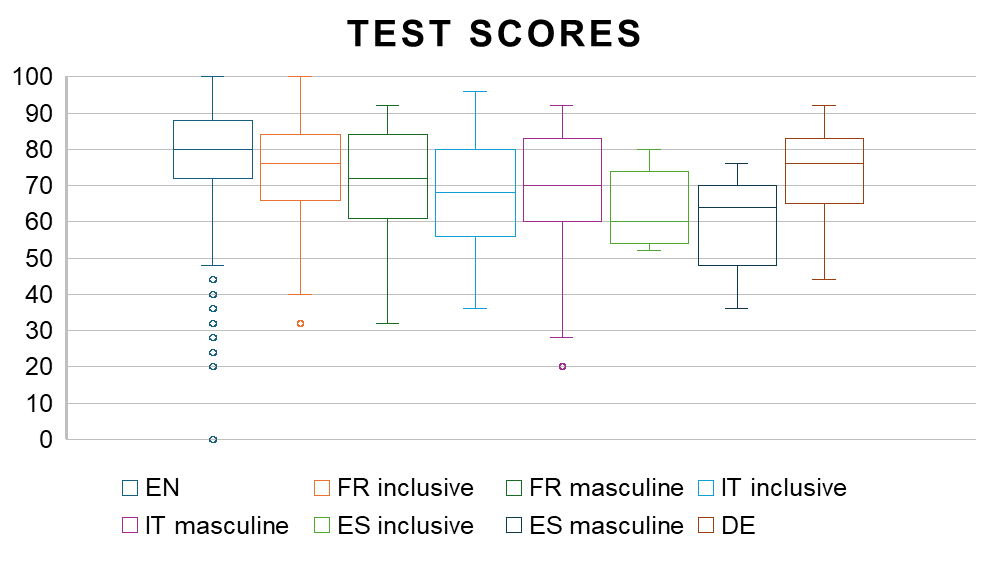

In addition to pass rate, we can look at the overall test scores (Figure 6). Comparing the scores for English (M=78, SD=14) with those for translations (M=71, SD=14), test takers scored significantly higher on the English tests, t(312) = 6.24, p < 0.001.

Figure 6. Distribution of test scores for all AR initial referee test attempts across languages and conditions

A two-sample t-test comparing English with French (M=72, SD=14) showed a significant difference in test score, t(171) = 4.12, p < 0.001. The same was true when comparing English with Italian (M=68, SD=17), t(45) = 3.84, p < 0.001; and when comparing English with Spanish (M=61, SD =12), t(14) = 5.01, p < 0.001. However, there was no significant difference between English and German (M=74, SD=12), t(25) = 1.55, p = 0.13.

When looking at the impact of condition (masculine versus inclusive) on test score for each language, there was no significant difference. An overview of the t-test results can be seen in Table 5.

| Language | Inclusive M (SD) | Masculine M (SD) | df | t-stat | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| French | 74 (14) | 71 (13) | 122 | 1.42 | 0.16 |

| Italian | 67 (15) | 68 (18) | 41 | -0.06 | 0.95 |

| Spanish | 63 (10) | 59 (13) | 10 | 0.61 | 0.56 |

Table 5. Two-sample t-test results comparing the test score (out of 100) between the inclusive condition and masculine condition for each language

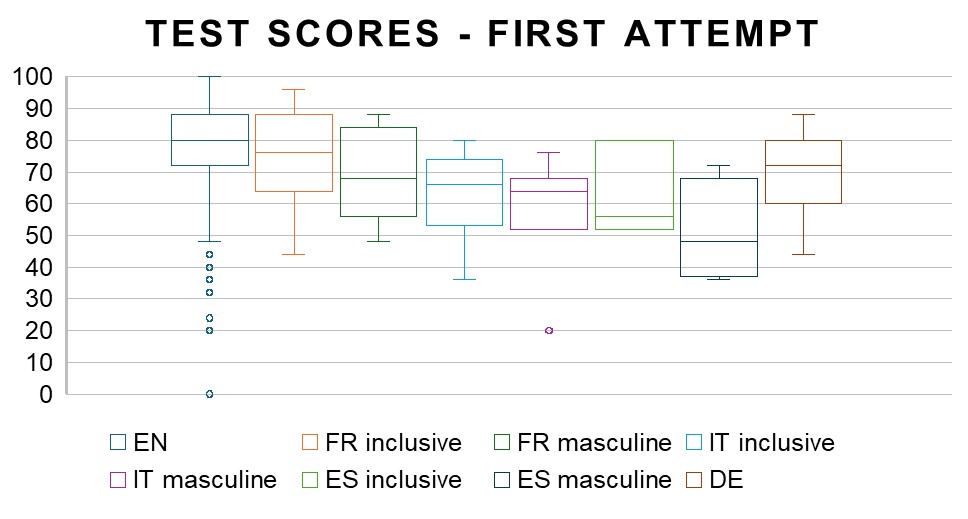

If we again limit the analysis to only the first attempt of each test taker (Figure 7), there was still a significant difference in scores between English (M=78, SD=15) and translations overall (M=69, SD=15), t(136) = 6.04, p < 0.001. Similarly, the difference between English and French (M=72, SD=14) was still significant (t(76) = 3.43, p < 0.001), as was the difference between English and Italian (M=60, SD=15), t(15) = 4.36, p < 0.001, and English and Spanish (M=56, SD=15), t(6) = 3.69, p < 0.05. Interestingly, the difference between English and German (M=69, SD=12) was significant here, with t(17) = 2.92, p < 0.01. As was the case for the whole dataset, condition (masculine versus inclusive) had no significant impact on test scores.

Figure 7. Distribution of first attempt test scores across languages and conditions

6. Discussion

6.1. Impact of language and translation strategy on texts

Based on existing reading research (Brysbaert, 2019), we would expect the German text to be shorter than the English text, and Italian, Spanish, and French to be longer, in that order. In the present study, the German text was much shorter (93% versus the expected 97.5% as suggested by Brysbaert) and the other languages led to longer texts (114% for Italian versus 100.6%, 120% for French versus 106.2%, and 122% for Spanish versus 102.5%). This can be due to differences in text types (expository paragraphs as opposed to referee tests) or the fact that Brysbaert used Google Translate instead of human translations. The specific gender-inclusive strategy chosen for German at the IQA only influenced 1.5% of words in the text, which is close to the 1% found for German press texts (Müller-Spitzer et al., 2024) and could support the argument that gender-inclusive language is likely to have limited impact on readability. For other languages, however, the textual impact was found to be more substantial, with anywhere between 16% (Italian) to 21% (French) of words being affected. Despite this seemingly large impact, we found no significant differences in character text length between masculine and inclusive variants (as many inclusive strategies simply replace a gendered grammatical ending by a neutral morpheme, such as the schwa for Italian or the ‘e’ for Spanish). However, there was still a significant difference in text length between English (shorter) and each of the inclusive language variants (longer) as well as between English and masculine Spanish. The strongest impact of strategy was found for French, where the inclusive variant led to a significantly higher average word length compared to the masculine variant. When comparing the English version with the translations, the masculine French version had similar average word lengths, whereas all other variants had significantly greater average word lengths.

6.2. Impact of language and translation strategy on readability

Combining what we know from existing reading rates (214 words per minute for French, 238 for English, 260 for German, 278 for Spanish, and 285 for Italian) (Brysbaert, 2019) with the measured text lengths in Table 2, we would expect people to need the least time to take the German referee tests (85% of the time needed to read English), followed by Italian, English, Spanish, and French (95, 100, 104, and 132% of the time needed to read English, respectively). As reading research suggests that an extra character in a word leads to +/- 20 ms extra reading time (Kuperman et al., 2024), we would expect people to need even more time when taking the French test in the inclusive condition. What the analysis showed, however, is that participants actually spent significantly more time on the English tests than on the Spanish test, and that there were no significant differences between English and the other languages. When the analysis was limited to each test taker’s first attempt only, the difference between Spanish and English disappeared. From a methodological and theoretical point of view, this suggests that text characteristics that explain reading rates in controlled experiments might not explain differences in reading rates in real-life timed test scenarios. Of course, test takers might spend additional time thinking about their answers before submitting them. An additional factor to take into account is the fact that many referee test takers are likely L2 speakers of English (based on NGB information) and that L2 speakers need more time to read (Dirix et al., 2020).

Contrary to expectations, and to the arguments of reduced readability raised by inclusive language opponents (De Santis, 2022; Johnson, 2024; Manesse, 2022; Universitat Oberta de Catalunya, n.d.), no significant difference was found between tests taken in the masculine and the inclusive conditions for any of the languages. This is in line with Girard et al. (2022) and Liénardy et al. (2023), who found no difference in reading speed, but contradicts Zami & Hemforth (2024), who found participants did take more time when reading an inclusive-language text in French. Although even in this last study, the effect decreased over time, suggesting that familiarity with inclusive language can mediate readability. Most test takers in the present study would already have been familiar with inclusive language.

6.3. Impact of language and translation strategy on test success

Another argument used against inclusive language is the supposed negative impact on comprehensibility (Burtscher et al., 2022; Daems, 2023; di Carlo, 2024; Friedrich et al., 2021; Manesse, 2022; Zami & Hemforth, 2024). The present study clearly showed that success rate was higher for people taking the English tests than for those taking the tests in translation, with overall more English tests being passed, test takers needing fewer attempts to pass, and obtaining higher average test scores. Only German test takers showed no significant difference in test scores compared to English. Of all the other variants, inclusive French actually seemed to perform best, with 75% of test takers eventually passing the test and needing only 1.74 attempts on average to pass (compared to 85% and 1.47 for English). A potential explanation could be that test takers with lower English proficiency (and thus the test takers more likely to take the test in a language other than English) are also less familiar with the IQA rules as a whole or that they have a harder time linking the concepts in one language to the concepts in the English rulebook. Due to the international nature of the sport, the quadball community predominantly uses English, and referees at international events are expected to make calls in English. At the time of this study, the IQA rulebook was only available in English, Catalan, French, and German, so Italian and Spanish test takers had no source material in their own language to learn from. Test takers might thus have been less familiar with quadball-specific concepts in other languages, even if they felt more comfortable taking a test in a language other than English. It is also likely that more experienced referees are comfortable taking the tests in English, whereas new players attempting to get certified would prefer to try a test in their native language first, leading to lower scores in translation compared to English. Interestingly, no significant differences in test scores were found between the inclusive and masculine condition for any of the languages. This confirms the hypothesis raised in Daems (2024) that inclusive versions would not lead to lower scores than masculine versions for IQA referee tests. This can again be explained by test takers’ familiarity with gender-inclusive language in the context of quadball or perhaps by their age. Research has shown that especially younger people are more positive towards visible gender-inclusive strategies (Abbondanza et al., 2025; Bruns & Leiting, 2024) and the average quadball player is younger than 30 (Fogg, 2022; Pennington et al., 2021; Reyes-Bossio & Vásquez-Cruz, 2024).

7. Conclusion and limitations

While arguments related to readability and comprehensibility have been raised against gender-inclusive language, these factors have rarely been tested empirically. Results from the limited existing psycholinguistic and self-paced reading experiments are inconclusive. To the best of the author’s knowledge, this study is the first time gender-inclusive language has been empirically put to the test in a high-stakes setting.

This study compared the impact of inclusive strategies for different languages (German, French, Italian, and Spanish) on text and word length and measured the speed and performance of quadball referees taking the official Assistant Referee initial certification test in the original English and in translation. For French, Italian, and Spanish, a masculine variant was compared to a gender-inclusive variant for the translated tests. As an explicitly gender-inclusive sport, quadball offers a space for trans and non-binary athletes who might not easily find a sense of belonging in more traditional sports. The language used by the International Quadball Association needs to reflect the values of the sport, yet even IQA translators have been reluctant to adopt inclusive strategies for all communication, especially in the context of the (timed) referee certification tests.

The present study suggests that, while inclusive strategies do impact the text itself, especially for French, this has no measurable impact on readability (as measured by time needed to complete the referee test) or on comprehensibility (as measured by test score). From a practical point of view, this means that IQA referee test takers do not need to be given extra time when taking a test in inclusive language and that no additional language resources need to be made available to make the community more aware of gender-inclusive language strategies, at least for the purpose of referee testing.

Perhaps a more worrying or striking result is the fact that test takers performed worse when they took a test in translation (average score of 71%) rather than the English test (average score of 78%), with the exception of German (average score of 74%). As the low score was not caused by test takers running out of time, this suggests that the current time limit imposed for the Assistant Referee certification test can be maintained for all languages for future IQA certification tests.

The ecological validity of this study is simultaneously its greatest strength and greatest limitation. Data were collected from the actual IQA referee test website, ensuring that the study effectively covers the entire population of interest and that actual performance was measured rather than simulated performance. This also reduces the level of control and the granularity of measurements. The variables of interest (time and score) currently cover the test as a whole, whereas it would be interesting to get a better idea of time and success rate for specific questions, potentially linking these to the degree of presence of gender-inclusive language in a question. Unfortunately, the IQA Referee Hub does not currently offer that level of control.

Working with a limited number of translation volunteers led to unexpected delays, causing some translations to be made available months before others. While there were quite a few test takers for French, the number of test takers for Spanish, Italian, and German is small, which means that those results need to be interpreted with caution. Many members of Spanish-speaking and German-speaking NGBs already took the English referee tests, possibly because they could not wait for translations to be made available, which might further have reduced the number of Spanish and German test takers. On the other hand, French is the language for which the inclusive strategy was found to be most disruptive to the text, so the fact that no differences in time and scores could be found for this language suggests that the findings for Italian and Spanish, where textual impact is much more limited, are likely valid as well.

Overall, this work suggests that gender-inclusive language does not negatively impact the speed or success of referees taking certification tests under time pressure, although performance was negatively affected by test takers taking the test in translation compared to English (with the exception of German, where test scores were similar). Future work could explore the comprehensibility of English versus translations in other IQA text types. Whether these findings extend to other sports remains to be seen, as the quadball community is very aware of the importance of gender inclusivity and gender-inclusive language. Future work could explore similar translation strategies in different sports communities, for these and other languages.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the International Quadball Association for their collaboration, in particular the translation volunteers for taking on additional work to make this study possible, and Marian Dziubiak for the technical implementation. I also want to thank the reviewers and editors for their detailed and thorough feedback, which I believe has greatly improved the final quality of this contribution.

References

Abbondanza, M., Galimberti, V., Bonomi, V., Reverberi, C., Durante, F., & Foppolo, F. (2025). Neutralizing gender in role nouns: Investigating the effect of ə in written and oral Italian. Frontiers in Communication, 9, 1530778. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2024.1530778

Abbou, J. (2024). Camille Circlude. 2023. La typographie post-binaire. Au-delà de l’écriture inclusive. GLAD!. Revue sur le langage, le genre, les sexualités, 16, Article 16. https://doi.org/10.4000/120hc

Bruns, H., & Leiting, S. (2024). Using gender-inclusive language in German? It’s a question of attitude . . . In F. Pfalzgraf (Ed.), Public Attitudes Towards Gender-Inclusive Language (pp. 97–126). De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783111202280-005

Brysbaert, M. (2019). How many words do we read per minute? A review and meta-analysis of reading rate. Journal of Memory and Language, 109, 104047. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2019.104047

Burtscher, S., Spiel, K., Klausner, L. D., Lardelli, M., & Gromann, D. (2022). “Es geht um Respekt, nicht um Technologie”: Erkenntnisse aus einem Interessensgruppen-übergreifenden Workshop zu genderfairer Sprache und Sprachtechnologie. Proceedings of Mensch Und Computer 2022, 106–118. https://doi.org/10.1145/3543758.3544213

Coady, A. (2024). The gender-inclusive language debate in France: A battle to save the soul of the nation? In Public Attitudes Towards Gender-Inclusive Language: A Multilingual Perspective (pp. 45–72). De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783111202280-003

Daems, J. (2023). Gender-inclusive translation for a gender-inclusive sport: Strategies and translator perceptions at the International Quadball Association. In E. Vanmassenhove, B. Savoldi, L. Bentivogli, J. Daems, & J. Hackenbuchner (Eds.), Proceedings of the First Workshop on Gender-Inclusive Translation Technologies (pp. 37–47). European Association for Machine Translation. https://aclanthology.org/2023.gitt-1.4

Daems, J. (2024). Pilot testing gender-inclusive translations and machine translations for German quadball referee certification test takers. In B. Savoldi, J. Hackenbuchner, L. Bentivogli, J. Daems, E. Vanmassenhove, & J. Bastings (Eds.), Proceedings of the 2nd International Workshop on Gender-Inclusive Translation Technologies (pp. 56–57). European Association for Machine Translation (EAMT). https://aclanthology.org/2024.gitt-1.6/

De Santis, C. (2022). L’emancipazione grammaticale non passa per una e rovesciata. Treccani Scritto e parlato. https://www.treccani.it/magazine/lingua_italiana/articoli/scritto_e_parlato/Schwa.html

di Carlo, G. S. (2024). Is Italy ready for gender-inclusive language?: An attitude and usage study among Italian speakers. In Inclusiveness Beyond the (Non)binary in Romance Languages (pp. 82–102). Routledge.

Dirix, N., Vander Beken, H., De Bruyne, E., Brysbaert, M., & Duyck, W. (2020). Reading Text When Studying in a Second Language: An Eye-Tracking Study. Reading Research Quarterly, 55(3), 371–397. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.277

Fiorentini, I., & Oggionni, R. (2024). ‘Anche la lingua deve adeguarsi’ La percezione pubblica del dibattito sul linguaggio inclusivo: La percezione pubblica del dibattito sul linguaggio inclusivo. In A.-M. De Cesare & G. Giusti, Lingua inclusiva: Forme, funzioni, atteggiamenti e percezioni (pp. 179–202). Fondazione Università Ca’ Foscari. https://doi.org/10.30687/978-88-6969-866-8/007

Fogg, J. (2022). QUK Member Survey 2021/22. https://chaser.cdn.prismic.io/chaser/c30731ce-852f-4e5c-a6fa-e1c8fe2bc463_QUK+Member+Survey+2021-22.pdf

Friedrich, M. C. G., Drößler, V., Oberlehberg, N., & Heise, E. (2021). The Influence of the Gender Asterisk (“Gendersternchen”) on Comprehensibility and Interest. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.760062

Friedrich, M. C. G., Muselick, J., & Heise, E. (2022). Does the use of Gender-Fair Language Impair the Comprehensibility of Video Lectures? – An Experiment Using an Authentic Video Lecture Manipulating Role Nouns in German. Psychology Learning & Teaching, 21(3), 296–309. https://doi.org/10.1177/14757257221107348

Gheno, V. (2024). Gender inclusiveness in a binary language: The rise of the schwa in Italian and the discussion surrounding it. In Inclusiveness Beyond the (Non)binary in Romance Languages (pp. 50–65). Routledge.

Girard, G., Foucambert, D., & Le Mené, M. (2022). Lisibilité de l’écriture inclusive: Apports des techniques d’oculométrie. Proceedings of the 2022 annual conference of the Canadian Linguistic Association, 1–15.

Greey, A. D. (2023). A part of, yet apart from the team: Substantive membership and belonging of trans and nonbinary athletes. Canadian Review of Sociology/Revue Canadienne de Sociologie, 60(1), 154–164. https://doi.org/10.1111/cars.12415

Gunther, S. (2022). Gender Dis-agreement: Reactions to Proposals for Gender-Inclusive and Gender-Neutral Language in France and Quebec. 48, 9.

IQA. (2023). Gender representation in quadball: Survey 2023 (p. 28). https://wpdev.iqasport.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/GenderRepresentationinQuadballSurvey2023.pdf

IQA. (2024). IQA Rulebook 2024. https://www.iqasport.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/IQARulebook2024.pdf

Johnson, P. (2024). Online attitudes towards gender-inclusive language in French. In F. Pfalzgraf (Ed.), Public Attitudes Towards Gender-Inclusive Language (pp. 73–96). De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783111202280-004

Koeser, S., Kuhn, E., & Sczesny, S. (2015). Just Reading? How Gender-Fair Language Triggers Readers’ Use of Gender-Fair Forms. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 34, 343–357. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X14561119

Kuperman, V., Schroeder, S., & Gnetov, D. (2024). Word length and frequency effects on text reading are highly similar in 12 alphabetic languages. Journal of Memory and Language, 135, 104497. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2023.104497

Liénardy, C., Tibblin, J., Gygax, P., & Simon, A.-C. (2023). Écriture inclusive, lisibilité textuelle et représentations mentales. Discours. Revue de linguistique, psycholinguistique et informatique. A journal of linguistics, psycholinguistics and computational linguistics, 33, Article 33. https://doi.org/10.4000/discours.12636

López, Á. (2022). Trans(de)letion: Audiovisual translations of gender identities for mainstream audiences. Journal of Language and Sexuality, 11(2), 217–239. https://doi.org/10.1075/jls.20023.lop

Manesse, D. (2022). Contre l’écriture inclusive. Travail, genre et sociétés, 47(1), 169–172. https://doi.org/10.3917/tgs.047.0169

Meuleneers, P. W. (2024). On the “invention” of the Gendersprache in German media discourse. In Public Attitudes Towards Gender-Inclusive Language (pp. 159–182). De Gruyter Mouton. https://www.degruyterbrill.com/document/doi/10.1515/9783111202280-007/html?lang=en

Müller-Spitzer, C., Ochs, S., Koplenig, A., Rüdiger, J. O., & Wolfer, S. (2024). Less than one percent of words would be affected by gender-inclusive language in German press texts. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11(1), 1343. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03769-w

Nodari, R. (2024). Gender-inclusive strategies in Italian: Stereotypes and attitudes. In F. Pfalzgraf (Ed.), Public Attitudes Towards Gender-Inclusive Language: A Multilingual Perspective (pp. 243–286). De Gruyter Mouton. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783111202280-010

Pabst, L. M., & Kollmayer, M. (2023). How to make a difference: The impact of gender-fair language on text comprehensibility amongst adults with and without an academic background. Frontiers in Psychology, 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1234860

Paolucci, A. B., Lardelli, M., & Gromann, D. (2023). Gender-Fair Language in Translation: A Case Study. In E. Vanmassenhove, B. Savoldi, L. Bentivogli, J. Daems, & J. Hackenbuchner (Eds.), Proceedings of the First Workshop on Gender-Inclusive Translation Technologies (pp. 13–23). European Association for Machine Translation. https://aclanthology.org/2023.gitt-1.2

Papadopoulos, B. (2022). A Brief History of Gender-Inclusive Spanish. 48, 9.

Papadopoulos, B., Cintrón, S., Hartman, C., & Rusignuolo, D. (2025). Italian. Gender in Language Project. https://www.genderinlanguage.com/italian

Pecorari, F., & Ferrari, A. (2024). L’inclusione di genere nei testi ufficiali, tra maschile inclusivo e pratiche di scrittura alternative. Le scelte della Svizzera multilingue con focus sull’italiano. Lingue e Culture Dei Media, 8(1), 82–94. https://doi.org/10.54103/2532-1803/24872

Pennington, R., Cooper, A., Faulkner, A. C., MacInnes, A., Greensmith, T. S. W., Mayne, A. I. W., & Davies, P. S. E. (2021). Injuries in Quidditch: A Prospective Study from a Complete UK Season. International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy, 16(5), 1338–1344. https://doi.org/10.26603/001c.28225

Pfalzgraf, F. (2024). Attitudes of the purist association Verein Deutsche Sprache (VDS) towards gender-inclusive use of German. A conceptual expansion of the term linguistic purism. In Public Attitudes Towards Gender-Inclusive Language (pp. 183–208). De Gruyter Mouton. https://www.degruyterbrill.com/document/doi/10.1515/9783111202280-008/html?lang=en

Reyes-Bossio, M., & Vásquez-Cruz, D. (2024). Habilidades Psicológicas Deportivas y estados de ánimo en jugadores peruanos de Quadball (Quidditch). Revista de Psicología Aplicada al Deporte y el Ejercicio Físico, 9(1), e4. https://doi.org/10.5093/rpadef2024a2

Rock, Z. do. (2021, August 6). Geschlechtergerechte Sprache: Von innen, unnen und onnen. Die Zeit. https://www.zeit.de/2021/32/geschlechtergerechte-sprache-diskriminierung-gendersternchen

Sauteur, T., Gygax, P., Tibblin, J., Escasain, L., & Sato, S. (2023). « L’écriture inclusive, je ne connais pas très bien… mais je déteste! ». GLAD!. Revue sur le langage, le genre, les sexualités, 14, Article 14. https://doi.org/10.4000/glad.6400

Schneider, C. (2020, March 5). Gender-Deutsch. Textschneiderin. https://textschneiderin.ch/gender-deutsch/

Sczesny, S., Formanowicz, M., & Moser, F. (2016). Can Gender-Fair Language Reduce Gender Stereotyping and Discrimination? Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 25. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00025

Slemp, K., Black, M., & Cortiana, G. (2020). Reactions to gender-inclusive language in Spanish on Twitter and YouTube. Proceedings of the 2020 Annual Conference of the Canadian Linguistic Association, 1–13.

Stahlberg, D., Braun, F., Irmen, L., & Sczesny, S. (2007). Representation of the sexes in language. In Social communication (pp. 163–187). New York: Psychology Press.

Stetie, N. A., & Zunino, G. M. (2022). Non-binary language in Spanish? Comprehension of non-binary morphological forms: a psycholinguistic study. Glossa: A Journal of General Linguistics, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.16995/glossa.6144

Stetie, N. A., & Zunino, G. M. (2024). Do gender stereotypes bias the processing of morphological innovations? The case of gender-inclusive language in Spanish. Psychology of Language and Communication, 28(1), 446–469. https://doi.org/10.58734/plc-2024-0016

Tibblin, J., Granfeldt, J., van de Weijer, J., & Gygax, P. (2023). The male bias can be attenuated in reading: On the resolution of anaphoric expressions following gender-fair forms in French. Glossa Psycholinguistics, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.5070/G60111267

Universitat Oberta de Catalunya. (n.d.). Uso no sexista de la lengua—Lengua y estilo de la UOC. Retrieved 1 April 2025, from https://www.uoc.edu/portal/es/servei-linguistic/redaccio/tractament-generes/index.html

Vecchiato, D. (2025). Translating non-binary narratives: A German-to-Italian perspective on gender-fair language in contemporary fiction. Lebende Sprachen. https://doi.org/10.1515/les-2024-0032

Waldendorf, A. (2024). Words of change: The increase of gender-inclusive language in German media. European Sociological Review, 40(2), 357–374. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcad044

Weber, L., Gygax, P., Schoenhals, L., & Fourrier, I. (2024). Ecriture inclusive et dyslexie: Enjeux, hypothèses et pistes de recherche. Approche Neuropsychologique Des Apprentissages Chez l’Enfant (ANAE), 36(188), 75–88.

Zami, J., & Hemforth, B. (2024). Intelligibilité de l’écriture inclusive: Une approche expérimentale. SHS Web of Conferences, 191, 10004. https://doi.org/10.1051/shsconf/202419110004

Zanin, A. C., LeMaster, L., Niess, L. C., & Lucero, H. (2023). Storying the Gender Binary in Sport: Narrative Motifs Among Transgender, Gender Non-Conforming Athletes. Communication & Sport, 11(5), 879–904. https://doi.org/10.1177/21674795221148159

Notes

- ORCID 0000-0003-3734-5160, e-mail: joke.daems@ugent.be

-

https://www.iqasport.org/about/members/↩︎

https://wpdev.iqasport.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/MEMBESHIPDATAANALYSIS.pdf↩︎

https://web.archive.org/web/20150209094242/http://www.iqaquidditch.org/rulebook8.pdf↩︎

The web calculator at https://astatsa.com/ created by Navendu Vasavada was used for this analysis.↩︎