Embodied Translation, Multimodal, and Situated

Communication:

An Ethnographic Study of Rink Hockey and Football Multilingual Teams in

Macau

Vanessa Amaro1, Macao

Polytechnic University

Júlio Reis Jatobá2,University of

Macau

ABSTRACT

This ethnographic study explores how multilingual athletes in Macau’s rink hockey and football teams translate strategy, affect, and identity across linguistic, bodily, and material boundaries. Drawing on extensive field observation, video analysis, and in-depth interviews, we examine communication through three interconnected lenses: translanguaging (the flexible use of entire semiotic repertoires), intersemiotic translation (converting meaning across speech, gesture, space, and objects), and experiential translation (the affective, embodied negotiation of meaning). On the rink, confined space and fast-paced play generate millisecond cues where verbal and gestural signals converge – Portuguese instructions are echoed in Cantonese and enacted through stick-taps. On the pitch, larger spatial layouts demand role-specific mediators: captains and goalkeepers switch between English, Portuguese, and Chinese codes, while gestures and referee signs help coordinate when words fail. In both sports, hybrid ‘team languages’ emerge, yet linguistic capital remains uneven; Portuguese and English often carry added weight, placing cognitive and emotional burdens on trilingual brokers. Moments of breakdown, such as injury stoppages and tactical disputes, expose how hierarchy, space, and affect decide who is heard and how meaning ultimately reaches others. We demonstrate that sport provides a living laboratory where translation is active: a continuous, multimodal choreography that maintains collective play while renegotiating notions of power and inclusion.

KEYWORDS

Translanguaging, intersemiotic translation, experiential translation, embodied translation, sport translation, multilingual teams.

1. Introduction

Multilingual sports teams reveal how people negotiate meaning across linguistic, cultural and bodily boundaries. In Macau, a Special Administrative Region of China where Chinese and Portuguese are the official languages3, with Cantonese and English widely used, and additional languages spoken within migrant communities4, rink hockey and football are prime sites for such negotiation. Amid this linguistic and cultural diversity, players and coaches must align physical execution, tactical plans, and shared affect – the intensities and emotional orientations that shape team response. This multi-layered alignment involves a set of strategic choices made under pressure that parallels translators’ situated decisions about codes, registers, and modes. Gestures, eye gaze, stick-taps, and timed silences are routinised in training and flexibly recombined in play. They often carry as much tactical force as talk. Together, these embodied cues and the alignment of physical, tactical, and affective dimensions form an adaptive repertoire. Yet the same diversity that enables this repertoire also produces misunderstandings, uneven proficiencies, and hierarchies that privilege the dominant code, echoing García and Cañado’s (2005) claim that language in multicultural teams is never neutral. Accordingly, we treat team communication as a site where power is exercised: who names a play, who is heard under noise and pressure, and whose signals become the norm. It is also a practical problem of inclusion for newcomers and for speakers with lower proficiency.

This study draws on three complementary perspectives. Translanguaging treats communication as the flexible use of a speaker’s full semiotic repertoire, dissolving clear language boundaries (García & Wei, 2014; Li, 2018) and highlighting the strategic mixing of verbal, visual and kinaesthetic resources. Kinaesthetic here refers to bodily movement, posture, rhythm and proprioceptive cues that organise timing and space in interaction (Baynham & Lee, 2019). While kinaesthetic signals provide the embodied means of coordination, affect shapes how such signals are interpreted and acted upon. Together with tactical and physical execution, these elements combine into the adaptive repertoire on which teams draw in practice. Intersemiotic translation – Jakobson’s (1959) term later also developed by Eco (2000) and Dusi (2015) – explores movement of meaning across sign systems; for athletes this occurs when lines and dots on a white board diagram become a skating pattern or a spoken command turns into a stick-tap. Experiential translation pushes this idea further, treating all translating as affective, sensory and relational – an embodied negotiation, not a simple transfer (Campbell & Vidal, 2024). Together, these three lenses – translanguaging, intersemiotic translation, and experiential translation (henceforth, TIE) – recast team communication as dynamic and multimodal: athletes, and teams, translate not only language but also space, rhythm and emotion through bodies, voices and objects. These lenses reveal that authority and belonging flow through semiotic choices, not just speech, and they cast inclusion as an ongoing accomplishment rather than a fixed condition.

This study takes rink hockey and football – two of Macau’s most prominent team sports – as contrasting arenas to explore how TIE dynamics unfold in markedly different physical and organisational settings. Rink hockey, institutionalised in Macau since the 1980s through formal leagues and club structures, takes place on a confined rink where Portuguese coaching terms blend with Cantonese side-line talk, and skaters rely on split-second gestures. Although rink hockey is less prominent than football, the Macau men’s senior rink hockey team5 regularly competes in major events such as the FIRS Rink Hockey B World Cup and the Rink Hockey Asia Cup. Football, with earlier roots in Macau and now organised through school leagues, community tournaments and the Macau Elite League, spreads communication across a full pitch. Club rosters typically include around 25-30 players from multiple nationalities and several working languages. Because only eleven are on the pitch at any time, long-range shouts, agreed codes and the relay role of captains and goalkeepers become pivotal, making verbal and non-verbal signals essential for coordination. These multilingual sports squads develop hybrid team cultures comparable to those observed in transnational organisational teams (Earley & Mosakowski, 2000; Lagerström & Andersson, 2003), where communicative norms are continually renegotiated. Such contrasts set the stage for asking how, in post-colonial and multilingual contexts like Macau, athletes continually translate strategy, affect, and identity across speech, gesture, gaze, and material cues.

Research on translanguaging has grown in classrooms and workplaces, yet we know less about how athletes in post-colonial contexts translate strategy, affect and identity moment by moment across speech, gesture, gaze and material cues. By strategy we mean both pre-planned routines (set plays, marking schemes) and rapid in-game adjustments; by affect we mean felt intensities and emotional orientations that circulate through teams, such as enthusiasm, frustration, confidence, doubt, expressed vocally, bodily and through tempo. These views are in line with experiential views of translation (Campbell & Vidal, 2024). However, previous studies often treat language as code, downplaying gesture and materiality (Pennycook, 2018; Blackledge & Creese, 2017), or celebrate creativity without examining power imbalances in language choice and the consequences for inclusion and exclusion, such as who gets addressed, trusted, or benched (García & Otheguy, 2020; Charalambous et al., 2016). Macau’s rink hockey and football scenes allow us to address both gaps and to show how each sport’s spatial grammar shapes these translations.

Accordingly, this article (i) maps the multimodal repertoires players and coaches use to coordinate action; (ii) shows how each sport’s spatial demands shape distinct forms of embodied rewriting; and (iii) asks when linguistic plurality becomes a shared asset and when it reinforces dominance. Data come from ethnographic fieldwork that combines participant observation, twelve hours of video and eleven semi-structured interviews with athletes, coaches and staff. Both authors entered the study with first-hand experience as team athletes, yet had already stepped out of active playing roles when formal fieldwork began. This insider vantage point provided intimate knowledge of routines while still positioning us as external observers – a combination that required ongoing reflexive vigilance (Adler & Adler, 1987; DeWalt & DeWalt, 2011; Hammersley & Atkinson, 2019).

The sections that follow integrate theory and data. First, we review the three analytic lenses of TIE; next, we outline methods; then we present findings for rink hockey and football, followed by a cross-sport discussion of power and inclusion. We conclude by arguing that athletes’ work of moving meaning across languages, bodies and histories invites a broader view of translation as relational action rather than text, echoing Butler’s (1993) conception of the body as a site of meaning.

2. Theoretical framework: embodied, multimodal, and situated communication

In Macau, the coexistence of multiple main languages (e.g., Cantonese, Portuguese, Mandarin, English) challenges the notion of language as a fixed, bounded code. Instead, this linguistic diversity highlights how language is fluid, hybrid, and dependent on context. Therefore, communication in Macau’s multilingual sports teams cannot be understood by treating language as a bounded code either and is better viewed as a dynamic, embodied, and multimodal practice shaped by three intertwined lenses: translanguaging, intersemiotic translation, and experiential translation, each of which has been developed in recent work across sociolinguistics, translation studies, and post-humanist theory.

Translanguaging refers to the strategic use of an individual’s full linguistic-semiotic repertoire (García & Wei, 2014). Instead of alternating between named languages, speakers blend resources to make meaning, negotiate relations and perform identities. Such fluidity is crucial in time-critical phases of play, such as line changes, counterattacks, and set pieces, where spoken instructions alone often fail. Bilingual students in Esquinca et al.’s (2014) classroom study likewise drew on all available modes to co-construct understanding. Baynham and Lee (2019) expand this view by emphasising that “translanguaging always involves a selection from available resources in a repertoire” that also heavily relies on “the visual, the gestural, and what can be communicated with the body or […] by the body” (p. 97). They note that this movement “takes translanguaging into the intersemiotic, multimodal domain” (p. 97), drawing directly on embodied resources. Their empirical work with basketball and the Brazilian martial art capoeira shows that “gesture was a significant feature […] but there seemed to be something beyond gesture in the way that bodies were implicated” (p. 106). In sport, bodies function as both medium and message, reinforcing Butler’s (1993) account of bodily performativity: the body is an active site of meaning-making that articulates intention, identity, and position through movement, gesture, and spatial presence, often beyond or without spoken communication. Translanguaging is therefore not only a communicative practice; it also challenges single-language norms and linguistic hierarchies and asserts agency.

Baynham and Lee (2019) remind us that the “trans-” in translanguaging implies “going beyond language as such” (p. 8), and that the term functions dynamically, as “something people do” (p. 98). This emphasis on the embodied and performative aligns closely with Li’s (2011) “moment analysis,” which foregrounds how translanguaging practices are shaped by histories, ideologies, and local contexts. Strategies and play have evolved within each discipline over time and at their own pace, with rules, regulations, and guidelines – both written and unspoken – shaping how performance is conducted, while discipline-specific ethics are often rooted in highly localised practices, sometimes leading participants to deviate slightly from the default framework. Sabino (2018) similarly critiques rigid, code-based perspectives and highlights the need for adaptive, relational strategies in multicultural environments. In such settings, teammates without any formal training, but who are bilingual, often take on the role of informal interpreters or linguistic mediators. They become key figures in facilitating communication and bridging cultural nuances within the team (Valero-Garcés, 2007).

The concept of intersemiotic translation further deepens this analysis by accounting for how meaning is transferred across different semiotic systems. Jakobson (1959) originally defined it as “an interpretation of verbal signs by means of signs of nonverbal sign systems” (p. 261), but subsequent scholarship has greatly expanded this view. Aguiar and Queiroz (2013), for instance, frame intersemiotic translation within Peircean semiotics, emphasising its basis in a triadic relation of sign, object, and interpretant that enables complex cross-modal interpretation. Dusi (2015) underscores the inherently “transcultural, dynamic and functional” nature of this process (p. 183), which operates across gesture, rhythm, visuality, and movement – elements especially prominent in sports contexts, where diagrams become drills, commands are rendered as cues, and gestures often replace speech altogether. Importantly, Dusi (2015) cautions that intersemiotic translation is “not simply a question of transposing or re-presenting in the new text the forms of the content and, where possible, the forms of the expression” of the source (p. 184). Instead, this process should be understood dynamically: it requires the translator to “reactivate and select the system of relations between the two planes in the source text” (p. 185) and meaningfully convey these relations within the expressive capacities of the target medium. This aligns with Eco’s view that translation is not word-for-word substitution but interpretive negotiation across semiotic and cultural frames (Eco 2000). Drawing on Peircean semiotics, Eco writes that “translation is a special case of interpretation” (p. 13) and that translators must decide “what the fundamental content conveyed by a given text is” (p. 31), reshaping it to preserve intended meaning even when surface forms change. Translation, for Eco, involves abductive reasoning – making informed bets about meaning and effect – rather than reproducing a fixed equivalence. In this view, every act of translation, whether verbal, visual, or bodily, involves re-articulating meaning through new signs shaped by context, culture, and intention.

In the realm of sport, this suggests that communication is not merely a matter of substituting gestures for words, but rather a dynamic process of embodied reinterpretation. Meaning is not transferred intact; it is reorganised through spatial awareness, physical presence, and affective intensity that make sense within the immediate logic of action. Building on this interpretive view of communication, Baynham and Lee’s (2019) notion of “intersemiotic translanguaging” highlights how verbal, visual, and embodied modes work together in dynamic, practice-based repertoires. For example, they describe how basketball coaching involves not just verbal strategies, but the use of magnetic boards, body modelling, and eye contact to scaffold understanding. Similarly, in capoeira, the instructor's verbal commands are synchronised with physical demonstrations, and “spoken language can be substituted by the embodied demonstration of a movement completely” (p. 110). In these interactions, meaning is co-constructed through speech, gesture, rhythm, and proximity, revealing communication as fundamentally relational and multisensory.

While translanguaging and intersemiotic translation account for the flexible, multimodal deployment of communicative resources, experiential translation foregrounds the affective, sensory and embodied dimensions of meaning-making. It shifts attention from semiotic systems alone to lived, subjective experience, where meaning emerges through presence, emotion and physical engagement. Building on Campbell and Vidal (2024), and resonating with Lee’s (2022) account of play and experimentalism, Boer’s (2023) phenomenological approach and Blumczyński’s (2024) work on translating experience, we treat translation as relational and performative, shaped by movement and co-creation. It is not the transfer of fixed content but an act of negotiation that embraces translator visibility and resists semiotic erasure. In sport, meaning is co-produced through gestures, spatial orientation and multisensory coordination, including haptic cues (touch, pressure, taps), auditory cues (claps, stick-taps, shouts), kinaesthetic/kinetic cues (movement, posture, rhythm, proprioception) and, where relevant, olfactory context that forms part of the ambient ecology rather than a primary tactical signal.

In multilingual sports teams, cohesion and strategy are built as much through embodied and affective coordination as through shared vocabulary (Zhu et al., 2020). Our focus is the ordinary, routinised flow of play; moments of breakdown enter the analysis only as diagnostic windows into how coordination is repaired. From this perspective, a breakdown is not a failure of linguistic competence but a temporary misalignment of attention, timing or expectation that is resolved through embodied negotiation. As Haapaniemi (2024) notes, “meaning is not and cannot be straightforwardly transferred or represented, because it is constructed through sensory and embodied experience” (p. 30). When a player mirrors a tactical movement or a coach demonstrates a drill, meaning travels via posture, rhythm and proximity. These are not secondary to spoken instructions; they are central to how meaning is made in team sport.

By embracing such embodied and multimodal translation practices, players and coaches participate in what Grass (2023) calls “translation as creative-critical practice” – a form of meaning-making that is experimental, situated, and affectively charged. This aligns with Campbell and Vidal’s (2024) description of translation as “a holistic, in-the-moment, often shared and plural process” (p. 3). Rather than viewing translation as a linear act of linguistic equivalence, experiential translation treats it as an emergent process shaped by movement, breakdown and repair, improvisation, and experimental play (Campbell & Vidal, 2024; Lee, 2022). In the high-pressure and fast-paced environment of competitive sports, this fluid and relational mode of communication becomes essential to team coherence and performance, revealing translation as an embodied practice deeply embedded in action and experience.

Because experience is always located, spatial theories round out the frame. We use location and situatedness in two linked senses: the physical infrastructure and material ecology of play (rink and pitch dimensions, boards, benches, whistles, lighting, weather) and the positioning of bodies in space (proximity, orientation, reach, speed). Pennycook and Otsuji (2015) describe spatial repertoires that crystallise when linguistic, material and bodily resources converge, drawing on Massey’s (2005) ‘throwntogetherness’ to stress space as relational and unfinished. Simon (2019) bridges these strands with the notion of translation sites, where infrastructures and embodied actors co-constitute practice. Baynham and Lee (2019) extend this to intersemiotic, multimodal repertoires; assemblage perspectives (Deleuze and Parnet, 1987; Canagarajah, 2018) model communication as the alignment of human and non-human elements improvising in real time. Nexus analysis (Scollon and Scollon, 2004) similarly locates meaning at intersections of discourse, practice and positioning. We refer to this as engaged situatedness: meaning emerges from actions that are materially embedded in place and accountable to its affordances and constraints.

Viewed together, these strands depict communication as the coproduction of a “translanguaged utterance selected from the repertoire” (Baynham & Lee, 2019, p. 110). Meaning is negotiated through bodies, objects and affects in motion, a picture consistent with the hybrid team cultures Earley & Mosakowski (2000) and Lagerström & Andersson (2003) document in transnational work groups. The confined rink of hockey and the expansive field of football impose different material grammars, shaping which semiotic cues rise to prominence, how quickly they must be read, and who gains or loses communicative leverage. Spectator proximity and stadium acoustics further condition audibility and visibility, altering the balance between spoken instructions and embodied signals. As Butler (1993) reminds us, the body is never a neutral vessel but an active site of knowledge, identity and resistance. The integrated TIE lens sketched here makes it possible to trace, in the sections that follow, how those participating bodies translate strategy, rhythm and emotion on wheels and on grass so that the respective team is organised and coordinated well in a fast-paced competition setting.

3. Methodology

This study employs a qualitative ethnographic design to examine communication in situ, attending to what team members do, how they talk about those actions, the settings in which they unfold, and the consequences that follow. In doing so, we align with openly ethnographic work in sociolinguistics and translation that foregrounds embodiment and spatial/material context (e.g., Pennycook & Otsuji, 2015; Blackledge & Creese, 2017; Baynham & Lee, 2019). Our focus is how multilingual athletes translate strategy, affect and identity across linguistic, bodily and material resources during training and competition. Such an approach yields the richly situated, sensory and multimodal picture that ethnography is designed to capture (Hammersley & Atkinson, 2019).

During 2024 we observed 50 training sessions, 12 competitive or friendly matches, and 3 team meetings, including pre-match tactical briefings (‘pep talks’) and a post-match review. All observations were on site. We recorded 12 hours of video across practices, games, and briefings, using researcher-shot footage and broadcast feeds when available. Recording settings varied by venue; for analytic consistency we sampled sequences where gesture, gaze, proxemics (Hall, 1966; Kendon, 2004), speech and key actions were legible. Field notes were organised to track the full semiotic palette, including speech, movement, proxemics (interpersonal distance, orientation and touch; Hall, 1966; Kendon, 2004) and material tools, used during coordination, instruction, conflict and celebration, with special attention to translanguaging, intersemiotic negotiation and embodied expression. We also constructed short vignettes from field notes and recordings to illustrate key interactional moments. Each vignette condenses a dated sequence (typically 5-30 seconds), with anonymisation, minimal glosses for non-English items and descriptions of salient gestures, gaze and spatial positioning.

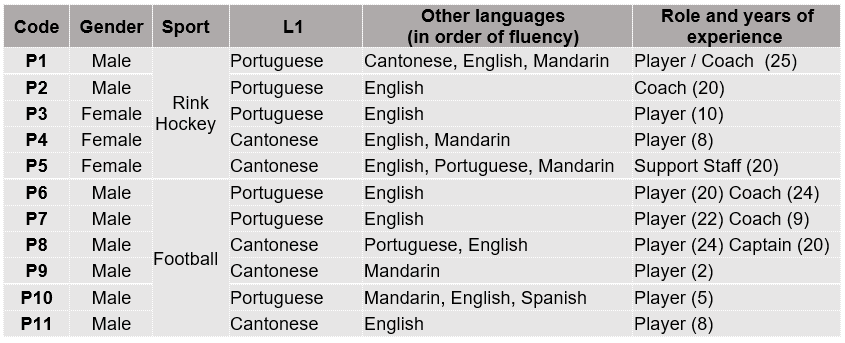

Additionally, we carried out 11 semi-structured interviews (45-70 min each), selecting participants through purposeful sampling (Patton, 2002) to capture diversity in linguistic background, team role (player, captain, coach) and experience. Interviews took place outside practice times. All sessions were audio-recorded, and because the researchers are fluent in Portuguese, English, and Chinese, each interview was carried out in the participant’s first language: one in Chinese and the remainder in Portuguese. Recordings were transcribed verbatim: we generated an automatic draft and then manually checked all transcripts against the audio. Selected segments originally written in languages other than English were manually translated into English by the authors. Thereafter, all files were anonymised and participants identified only by neutral codes (see Table 1). Interviewees were reminded of their right to withdraw at any time without consequence.

Table 1. Profile of interviewed participants

Both authors brought first-hand playing experience – Researcher A in rink hockey (2012-2022) and Researcher B in Macau’s professional football league (2019-2023) – yet had stepped away from active rosters before formal fieldwork began. This previous insider vantage point granted backstage access while demanding continual reflexive vigilance. Each researcher kept a field journal, triangulated observations with video and peer feedback, and engaged in iterative analytic dialogue to expose blind spots (Adler & Adler, 1987; DeWalt & DeWalt, 2011). Positionality remained a central reflexive theme. Following Pillow’s (2003) call for critical self-interrogation, we treated subjectivity not as methodological flaw but as a resource. In practice, prior relationships often facilitated access to locker rooms and briefings, helping to build rapport. However, there was also a risk of over-familiarity, which is why we took specific precautions. We mitigated this by observing from the periphery, avoiding team gear, and refraining from speaking during drills; scheduling interviews outside practice times and avoiding translation or advice; writing bracketing memos before and after each session to record assumptions; noting any ‘insider inferences’ in our analytic notes and seeking confirmation through video review or a second coder; swapping roles when sequences involved close former teammates, so the other researcher led the interview and primary coding; and conducting brief member checks on selected vignettes to verify our interpretations.

Data were analysed thematically following Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six-phase approach: familiarisation with the data, generation of initial codes, identification and review of themes, definition and naming of themes, and production of the final analysis and its narrative. This process enabled a systematic yet flexible engagement with the material across multiple sources, including field notes, video excerpts and interview transcripts.

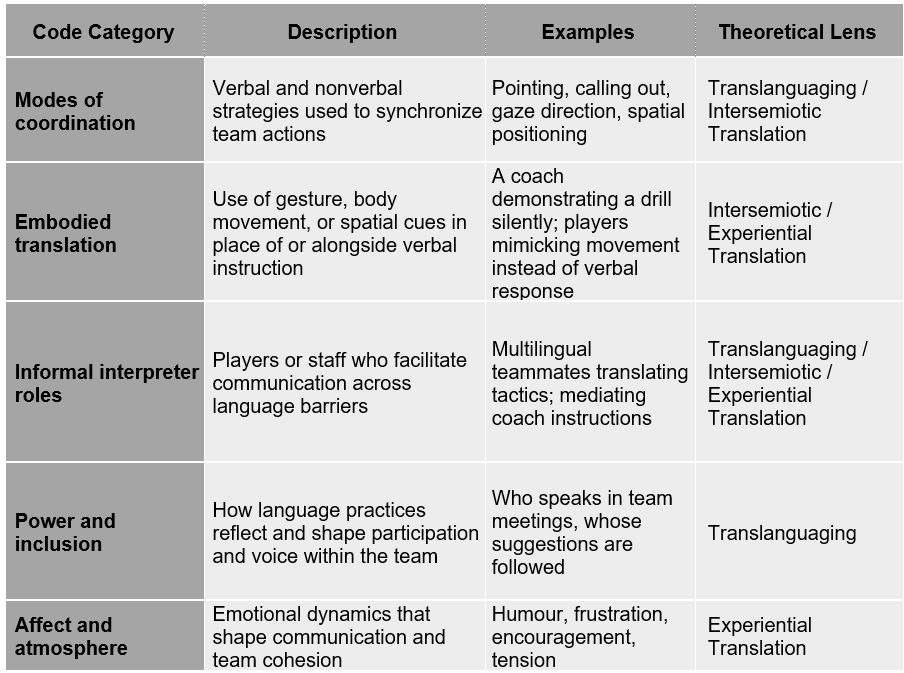

Coding proceeded in two passes. In Pass 1 (inductive/open), we generated data-driven codes such as micro-cues (stick-taps, claps, hand signals), gaze locks and pointing, proxemics (huddles, line shape, box defence contraction), spoken tokens (e.g., linha alta, costas, meu; faai dī, nī douh; “man on,” “easy”), set-piece routines (corner set-ups, face-off patterns), breakdown/repair episodes (misread runs, delayed presses followed by re-alignment), and material scaffolds (magnetic board use, cone layouts). In Pass 2 (theory-guided), we grouped and refined these under sensitising concepts: (i) translanguaging –cross-language utterances and relays (coach→captain→backs), hybrid calls (e.g., “Caralho, play easy lō”), emergent team lexicon; (ii) intersemiotic translation – speech→gesture or diagram→drill mappings (e.g., double clap + point standing in for ‘short then switch’; board arrows enacted as skating lines); and (iii) experiential translation – affective and sensory markers tied to coordination (tone escalation, celebratory stick-tap chains, touch for reassurance after fouls, tempo hush during referee signals). Initial codes thus came from the data; the TIE lens served to organise and interpret them rather than to pre-impose categories. For each coded sequence we also logged initiator, recipients and outcome (alignment or misalignment). These codes were then organised into thematic categories that captured both functional and affective dimensions of meaning-making in multilingual sports contexts. A full list of codes with brief examples appears in Table 2.

Table 2. Thematic codes used in data analysis

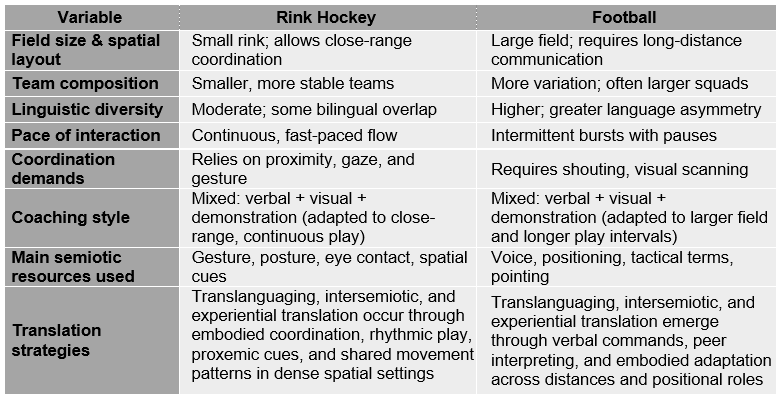

A comparative matrix was used to assess communication strategies across rink hockey and football, incorporating variables such as field size and spatial distribution, team composition, linguistic diversity, pace and type of interaction, coordination demands, coaching styles, and the semiotic resources employed. This comparative approach allowed for a nuanced understanding of how TIE practices were shaped by each sport’s specific spatial and communicative affordances (Creswell, 2013). Notably, football often required long-range spoken instructions and positional adaptation, whereas rink hockey relied more heavily on close-range coordination, proxemics, and gestural interaction. Table 3 presents a breakdown of these contrasts, highlighting the distinct semiotic ecologies and translation strategies that emerged in each sport.

Table 3. Comparative Framework: Rink Hockey vs. Football

The trustworthiness of this study was enhanced through triangulation (observations, video recordings, interviews), peer debriefing with two external colleagues (each proficient across the study’s three languages and familiar with competitive sport settings) at key analytic junctures, and member checking (sharing a few anonymised vignettes with participants to confirm factual accuracy). Peer debriefing, in which we presented excerpts and preliminary codes to colleagues who were not part of the fieldwork and invited them to question our readings, prompted small refinements to codes and themes. Some sequences were treated as affective translation based on intonation (prosodic tone), rhythm and embodied intensity.

4. Analysis

Before presenting the analysis of communication practices in rink hockey and football, we briefly outline the historical and sociolinguistic context in which these sports have developed in Macau. Both were introduced during the Portuguese administration and have since evolved within the region’s distinctive postcolonial and multilingual environment.

Rink hockey was institutionalised in the 1980s and reached global competition by 1984. Once dominated by Portuguese players and with instruction then typically in Portuguese and English, the sport revived in the early 2000s, with the Sports Bureau noting a ‘revival’ in 2004 and funding two coaches to work with children, and youth categories such as U19 and U14 becoming regular pathways into selection for local Chinese and Macanese players (ID, 2004). Government-subsidised and widely accessible, rink hockey provides a dynamic setting where players must coordinate through embodied strategies and translanguaging across languages and modalities.

Football, introduced even earlier in the colonial period, remains institutionally underdeveloped. While the sport enjoys grassroots popularity, particularly through school leagues and community-based competitions, as the Bolinha6 Cup, professionalisation stays limited because Macau is one of FIFA’s smallest associations, faces chronic space and pitch shortages, and most senior players are amateurs (JTM, 2013; Inside FIFA, 2020). Instruction varies by school and academy – some use only Cantonese, while others offer multilingual training environments, including Portuguese and English. The result is a linguistically stratified field where communication practices differ greatly depending on the context.

In Macau, both rink hockey and football are practiced in multilingual and multicultural settings, making them rich sites for examining how players and coaches coordinate action, negotiate meaning, and build cohesion across linguistic boundaries. The following analysis draws on these dynamics to explore translanguaging, intersemiotic translation, and experiential translation in practice.

4.1. Rink hockey

In training for Macau’s senior men’s and women’s rink hockey representative teams, communication blends speech, gesture, ad hoc translation, and embodied demonstration. Coaching is primarily in Portuguese, reflecting the coaches’ backgrounds. English is used as a bridging code, especially in mixed-line briefings and when introducing new drills, and, even then, several players in both squads still need Cantonese translation. Across both teams, coaches and teammates rely heavily on gesture and physical demonstration to secure understanding.

Players quickly learn a shared working lexicon of Portuguese rink terms: baliza (shoot), cruza (cross), tabela (side), passa (pass), bloqueio (block), and meio (middle). When new tactical drills are introduced, the coach typically explains verbally or uses a magnetic board, first cueing a Portuguese-native player to physically demonstrate the sequence for everyone else. Portuguese speakers therefore tend to line up first for these exercises, with non-Portuguese speakers observing closely and mimicking. The coach will at times supplement instructions in English to bridge gaps, and non-Chinese-speaking players also pick up frequent Cantonese calls on the rink: nī douh (呢度, here), gó douh (嗰度, there), fāan wùih (返回, return), tūng gwo (通過, pass), which become mutually intelligible in play even when tones are not perfect.

Vignette 1 – Translanguaging drill (12 Mar 2024)

Coach (Portuguese): Cruza–tabela–meio!

The lead Portuguese forward repeats the call, then skates the pattern while shouting “tūng gwo!” (Cantonese ‘through-pass’). Two Cantonese players rookies echo “meio… tūng gwo” and copy the movement – showing a Portuguese cue instantly glossed in Cantonese and embodied in action.

During drills and practice matches, players mainly communicate through physical actions. They often use their hockey sticks to point out strategic positions or specific actions, tap the rink or point their sticks to indicate direction, rely on facial expressions – such as nodding toward a direction to signal movement – making eye contact to confirm they're ready, or using quick hand signals to show passing or shooting intentions. Additionally, players raise their hands to mark opponents or request assistance. Verbal expressions, in both Chinese and Portuguese, combined with gestures, strategic positioning, and physical cues such as tapping skates on the rink or making subtle body shifts, form a shared communicative repertoire. Gradually, this repertoire evolves into a hybrid team language, seamlessly integrating verbal and non-verbal cues drawn from multiple linguistic systems.

However, tactical misunderstandings, unequal language proficiencies, and communicative hierarchies often affect participation and coordination during training and matches. Miscommunication typically occurs when players fail to fully comprehend verbal instructions or misinterpret physical signals. Such misunderstandings can result in incorrect positioning, delayed reactions, or disrupted coordination. Non-Portuguese speakers sometimes struggle to grasp detailed tactical explanations, relying heavily on visual cues or the immediate physical actions of teammates. Additionally, this linguistic imbalance occasionally reinforces communicative hierarchies, with players fluent in the primary coaching language (Portuguese) assuming informal outspoken, senior or even leadership roles, which may inadvertently marginalise others who face greater linguistic barriers. Occasionally, misunderstandings escalate into open conflict during practice matches. Among Portuguese players the response is often immediate and forceful – pushing, aggressive body language, or heated verbal exchanges – whereas Chinese players typically turn away from provocation and continue play (see also Krys et al. 2017). When tensions rise, coaches step in to mediate, sometimes removing the instigator from the rink and sending in a substitute until tempers settle.

These complexities of multilingual and multicultural communication become particularly evident under real-time competitive pressures. To further examine these dynamics, we analysed footage of an international rink hockey match in which Macau’s senior male team (wearing white shirts and green shorts) hosted a Portuguese club. The starting lineup of the home team featured a Chinese goalkeeper (Mandarin speaker), two Portuguese players, one Macanese player (Cantonese/Portuguese speaker), and one Chinese player (Cantonese speaker) – highlighting the team’s linguistic and cultural diversity. Given the international nature of the match, a determination to perform well on home ground was noticeable and perhaps even evident.

As the visiting team dominated possession, the intensity of communication among Macau’s players increased, with commands in Portuguese such as fica (stay), olha (look), passa (pass), vai (go), and meu (my/mine) frequently shouted across the rink (Frame 1). Following a crucial save, the goalkeeper struck their stick on the floor repeatedly – both to celebrate and to prompt a swift counterattack. The coach, visibly tense, continued issuing instructions in Portuguese costas (behind), fecha (close), tira a bola (take the ball) – demonstrating how verbal language was prioritised during defensive transitions. When one of the Portuguese players scored the match’s first goal, the two Portuguese players celebrated with a handshake and stick tap (frame 2) before the entire team joined in, tapping their sticks together.

|

|

|---|---|

| Frames 1 and 2 (photographs by the authors) |

|

Vignette 2 – Intersemiotic cue (18 Apr 2024, international match)

Captain shouts Costas! (‘behind’).

The goalkeeper pounds the rink three times with their stick, points the blade left, and all four players instantly contract into a box defence – verbal instruction converted into percussive signal and collective movement.

Moments of non-verbal communication were equally prominent. In one sequence, the Portuguese captain gestured to a Chinese teammate to mark an opponent (Frame 3). Throughout the game, players frequently relied on hand signals, head nods, and stick pointing to direct attention and coordinate movement (Frame 4). These embodied actions, consistent with observations and interviews, proved essential for conveying condensed? meaning quickly during intense play.

|

|

|---|---|

Frames 3 and 4 (photographs by the authors) |

|

Another illustrative moment occurred after a collision in which the goalkeeper remained on the ground. Several players raised their hands in frustration. A Portuguese teammate approached and asked in English what had happened, later translating the goalkeeper’s explanation into Portuguese to the Macanese referee (Portuguese and Cantonese speaker) and using a hand gesture to indicate a groin injury. While the injured player received assistance, the captain summoned a Macanese and a Chinese player to provide tactical instructions. Speaking in Portuguese and gesturing toward specific zones on the rink, the captain relayed strategic feedback, which the Macanese player partially translated into Cantonese (Frame 5).

Frame 5 (photograph by the authors)

Vignette 3 – Experiential translation of affect (same sequence)

Pain, protest, and repositioning flow through touch, raised arms, whispered Portuguese, and a rink-side diagram traced with a stick. Emotion and strategy travel bodily rather than verbally, showing how affect is “translated” in action.

Significantly, communication patterns varied with team composition. When four Portuguese players were on the rink, verbal interaction increased – often accompanied by expressions of frustration or encouragement in Portuguese. However, when P1, who is a trilingual player, entered the game with two Chinese teammates, the communication shifted to a mix of Cantonese and Portuguese. This situational flexibility underscores the dynamic nature of translanguaging during gameplay.

Interviews with players and coaches revealed further nuances in communication practices that extend beyond surface-level translation. One key informant, P1, a senior player fluent in Portuguese (L1), Cantonese, and English, frequently assumes the role of an informal mediator during both training sessions and games. They described their translanguaging practices in a way that illustrates the fluidity and adaptability required in their multilingual environment:

In training, I often have to switch between Portuguese and Cantonese, sometimes even English, depending on who I’m talking to. It’s not just about translating words; it’s about making sure everyone understands the strategy. Sometimes, it’s a mix – two words in Portuguese, three in Cantonese.

P1’s account highlights a form of spontaneous, flexible language use that goes beyond conventional interpretation. Their role involves not only linguistic translation but also the intersemiotic adaptation of tactical concepts to ensure shared understanding across different linguistic and cultural backgrounds. This translanguaging approach enables smoother interpersonal coordination, especially in high-pressure situations where clarity and speed are crucial. Moreover, their code-switching is shaped not only by linguistic competence but also by relational dynamics – choosing which language or phrase to use depending on familiarity, authority, and context. Such practices exemplify how communication in multicultural sports teams operates through layered, context-sensitive strategies rather than rigid language boundaries.

P1’s account also reflects a fluid approach to translanguaging grounded in embodied practice. They further explained: “We mix everything – every language, everything. I constantly have to switch between different languages, whether during practice or matches. But using gestures is just as important because sometimes it’s hard to shift languages quickly.” Here, language is not deployed in isolation but in tandem with physical cues such as gestures, tone, and proximity. These multimodal resources help bridge linguistic gaps and support rapid comprehension in motion. This mix of verbal and non-verbal strategies contributes to the formation of a hybrid team culture, in which communicative practices evolve organically.

The team coach P2, who primarily communicates in their mother tongue, Portuguese – supplemented by a limited repertoire of Cantonese terms and occasional short sentences in English – described how hybrid communicative practices gradually become embedded in the team’s routines. They observed: “Over time, we develop routines. Even players who don’t speak Portuguese start to pick up words like marca (mark), baliza (goal), or rápido (quickly). These words become part of our shared vocabulary.” Their account underscores how repeated exposure to key tactical expressions – often embedded in highly contextualised and embodied interactions – facilitates the development of a functional multilingual lexicon. This emergent “team language” is not formally taught but rather internalised through practice and repetition, becoming a crucial component of collective coordination. It illustrates how translanguaging evolves into a stable communicative code, blending linguistic elements across Portuguese, Cantonese, and English to meet the real-time demands of gameplay.

Such routines foster what players often describe as a “team language” – a shared communicative repertoire forged through ongoing interaction. This repertoire draws not only on translanguaging but also on non-verbal strategies such as gestures, proxemics, and even strategic silences, forming a pragmatic and flexible code intelligible primarily to insiders. Celebratory expressions – such as Bem feito! in Portuguese, hóu hóu! (好好) in Cantonese, and “Good job!” in English – symbolise and reinforce this hybrid identity, marking moments of collective achievement and emotional connection.

Player P3, who joined the women’s team around a decade ago, emphasised the process of adapting to this “team language,” which encompasses far more than verbal commands. They highlighted how sustained training also cultivates a form of tacit, embodied communication:

After a while, you know each other so well that you don’t need to speak. A look, a tap, or just calling someone’s name is enough to get the message across. Gestures or movements often speak for themselves. It’s often easier to show than explain.

P3’s reflection captures how shared physical routines and spatial awareness gradually reduce reliance on explicit verbal communication, allowing players to act and react fluidly within the game’s fast-paced environment. This deepening of non-verbal rapport further illustrates how communication in multilingual sports teams is distributed across bodies, languages, and spaces – coalescing into a dynamic, adaptive system of meaning-making.

While the team’s multilingual practices foster a shared communicative repertoire, the use of Portuguese often appears to carry greater weight. As most coaches communicate primarily in Portuguese and many players interact in Portuguese among themselves, the language tends to occupy a dominant position within the team’s hierarchy of codes. This subtle privileging of Portuguese may shape linguistic norms and affect players’ sense of inclusion. P4, whose native language is Cantonese and who has acquired some Portuguese along with a basic command of English, pointed to the persistence of informal linguistic groupings within the team: “Small groups form naturally – Cantonese speakers stick together, Portuguese speakers the same. It doesn’t disrupt the game, but it’s noticeable outside the rink.”

P4’s observation suggests that while multilingual communication is functional and often effective during matches and training sessions, language boundaries continue to influence social dynamics off the rink. The tendency for players to cluster according to shared linguistic backgrounds may reflect differing levels of confidence in the dominant language, as well as deeper cultural affinities and comfort zones. These groupings reveal how language can serve both as a bridge for tactical coordination and as a boundary marker in moments of informal interaction, potentially shaping players’ experiences of belonging and cohesion in complex ways.

P1 echoed this observation, highlighting the mental demands of navigating multiple languages: “In the heat of the moment, you’re not just thinking about the play – you’re also figuring out how to communicate. Should I use Cantonese, Portuguese, or English? It adds another layer of decision-making.” At times, however, this multilingualism becomes an asset. With a smile, P1 remarked: “We mix languages so much that it can confuse opponents. They don’t know what we’re saying.” This comment underscores the strategic dimension of translanguaging – not only as an internal team resource but also as a way of broadening the concept of instant translation and a communicative tactic with external effects.

P3, a former figure skater who transitioned to rink hockey at the age of 17, offered a distinct perspective on the challenges of linguistic and cultural adaptation within the team. Coming from an individual sport where performance relies solely on personal rhythm and precision, they described the difficulty of adjusting to a collective, fast-paced, and multilingual environment: “In figure skating, everything depends on yourself – your timing, your rhythm. But in hockey, you depend on others. And when they don’t speak the same language, it’s hard to feel part of the team at first.” They recounted how disorienting it was to navigate a training environment where Portuguese, Cantonese, and English were interwoven, especially before they had acquired basic familiarity with key hockey terminology. In the absence of shared vocabulary, they relied on non-verbal cues and embodied interpretation to learn and integrate into team routines: “There were moments when I didn’t know what anyone was saying. I just tried to watch and followed the first in line.” In our framework this is translation in action, intersemiotic and experiential: movement, gaze and spacing carry the message when words do not.

P3’s experience highlights the role of observation, imitation, and physical alignment as crucial strategies in multilingual team sports, particularly for newcomers with limited language proficiency. Their narrative underscores that adaptation in such settings is not only linguistic but also corporeal – requiring athletes to read gestures, body positioning, and spatial patterns as part of a broader intersemiotic communicative process. This reliance on embodied learning reflects the practical realities of multilingual coordination and the often-overlooked cognitive and emotional labour involved in becoming part of a team.

While P3’s story offers a personal view of this learning process, it echoes broader patterns across the dataset. Together, our analysis shows that translanguaging in rink hockey is not a mere workaround but a socially embedded, embodied practice. Alongside it, intersemiotic translation is constant: white-board diagrams, spoken cues and referee signals are rendered as skating lines, stick taps, gaze direction and spacing. Experiential translation is equally central: affect and sensation, such as tempo, confidence, frustration, and touch, influence how coordination is felt and repaired in play. These practices are shaped by players’ positionalities, histories and repertoires, and by the real-time demands of the sport. The strategic mix of language, gesture, gaze and proxemics lets players coordinate smoothly across differences, helps build cohesion, and also shows how power and inclusion are at work. In this sense, communication in Macau’s rink hockey teams is both a challenge and a resource, an evolving language of sport negotiated in real time on wheels.

4.2. Football

Football’s global appeal means that even people who have never played often recognise its basic vocabulary and tactics. Yet within a squad of 30 athletes representing 12 nationalities and speaking nine languages7, can we truly speak of a ‘universal football language’? P6, the head coach, who was a former professional who played in Portugal, Brazil, Colombia, and for Macau’s senior national team, insists that communication problems are rare. “Words often aren't necessary; a gesture or a glance usually suffices,” they explain. Still, echoing Romário’s saying, they remind their players that “training is training, and a match is a match”8: the silent fluency displayed on game day rests on the spoken – and sometimes heated – discussions that take place on the training pitch. This contrast foreshadows the team’s translanguaging practices and underscores the affective, experiential nature of communication in sport (Campbell & Vidal, 2024).

Training observations showed players clustering into three main linguistic groups: English, Portuguese, and Chinese (mostly Cantonese). English functioned as a shared second language, while the Portuguese and Chinese groups comprised mostly native speakers. Informal interpreters – also called language brokers or linguistic mediators – are bilingual insiders who, without formal training, step in to translate and paraphrase on the spot so that interaction can continue smoothly (Valero-Garcés 2007; Orellana & García-Sánchez, 2023). In this team, such brokers emerged organically, and the coach formalised the role by appointing a trilingual player as both captain and designated ‘translator’. P6 explained that players gradually developed a shared ‘football language’ through gestures and movement: “It is in the gestures that they ‘read’ the teammates.” Leadership, they stressed, was central: when a player showed communicative and social ability, they became captain – “my bridge to introduce my ideas.”

Vignette 4 – Translanguaging huddle (pre-season drill, 21 Jan 24)

Coach (English/Portuguese mix): “Back four, linha alta – high line!”

Captain repeats in Cantonese, keeps linha alta intact.

Goalkeeper yells “linha… high line, faai di!” to Chinese full-backs.

Three codes circulate in ten seconds, crystallising a hybrid term everyone now uses.

The captain’s command of Portuguese, Cantonese and English affords him a natural legitimacy as the team’s linguistic go-between. As García and Cañado (2005) note, fluency in prestigious languages often confers informal authority. The coach praised not only the captain’s multilingualism but also their humility, calling him “a second coach on the pitch.” Even so, the task of real-time orchestration does not fall on him alone. Echoing Earley & Mosakowski (2000) emphasis on distributed leadership, the coach emphasised that the goalkeeper – due to their panoramic view of the field – acts as the team’s chief in-game communicator: “He can even shout instructions to the captain.”

Field observations reveal a clear functional split among the squad’s three working languages. English operates as the shared lingua franca for group-wide instructions and standard football jargon – line, cross, free kick, corner, first post, second post, man on, easy easy, out out. Portuguese, exchanged among native speakers, carries more coded tactical cues and occasionally doubles as a ‘secret’ channel against Chinese-speaking opponents: fora de jogo (offside), polícia (man on), rebenta (play strong), quebra (tactical foul), chão (slide tackle), and segue (advantage rule).

In our training observations, we noticed that Chinese is the least used language on the team, with no collective tactical instructions observed in Cantonese or Mandarin. However, specific terms appear in interactions – especially between the Portuguese-speaking goalkeeper and Chinese defenders. As an example, we highlight these words that are commonly used in the team: in Cantonese, faai dī, faai dī (快啲 faster), díu (屌 fuck off); in Mandarin, lái lái (来来 to come), wǒ lái (我来 it's mine/leave it to me), wǒ / wǒ de (我/我的 I/mine).

Vignette 5 – Intersemiotic cue (training game, 03 Apr 24)

Portuguese midfielder claps twice, points at turf → winger sprints into channel.

No words; later they explain: “clap means curto, point means vira” – short then switch.

Gesture plus sound compresses two Portuguese commands into an instantly legible sign.

Expletives and emphatic markers on the pitch draw far more heavily from Portuguese and Cantonese than from English. Typical outbursts include Portuguese invectives – caralho (cock), porra (damn), foda-se (fuck) – and Cantonese swears such as díu 屌 (fuck off), díu néih 屌你 (fuck you), díu néih lóuh móuh 屌你老母 (motherfucker). Cantonese sentence-final particles – a 呀, àaih 唉, nī/nēi/nē 呢, lō 囉 – also punctuate talk, intensifying or softening commands. Players routinely braid all three languages into single utterances, as in the sideline cry “Caralho, play easy lō!,” which pairs English syntax with a Portuguese obscenity and a Cantonese particle. Such hybrid speech captures translanguaging as creative assemblage (Baynham & Lee, 2019; Canagarajah, 2018).

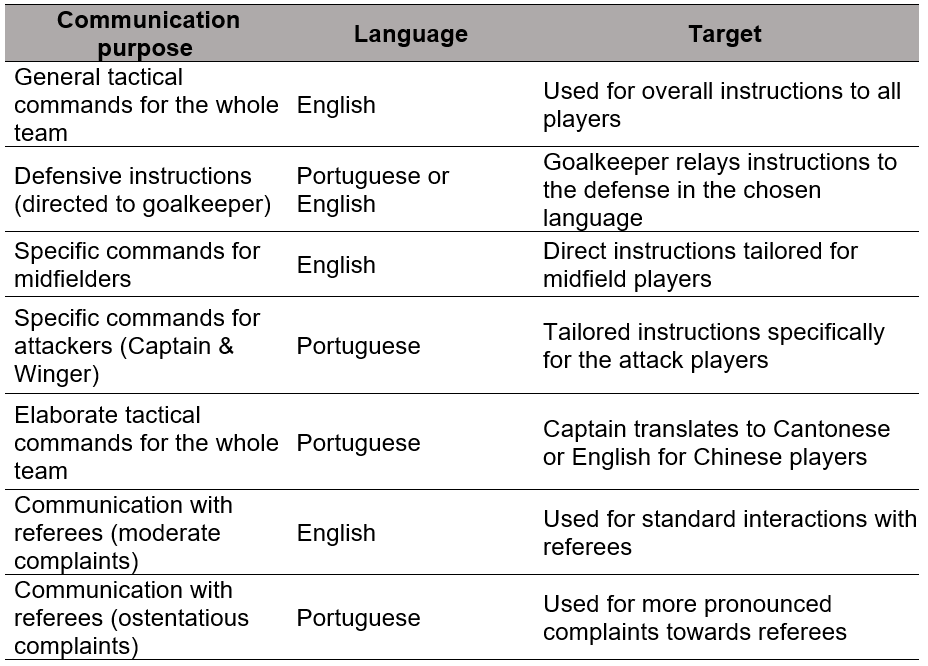

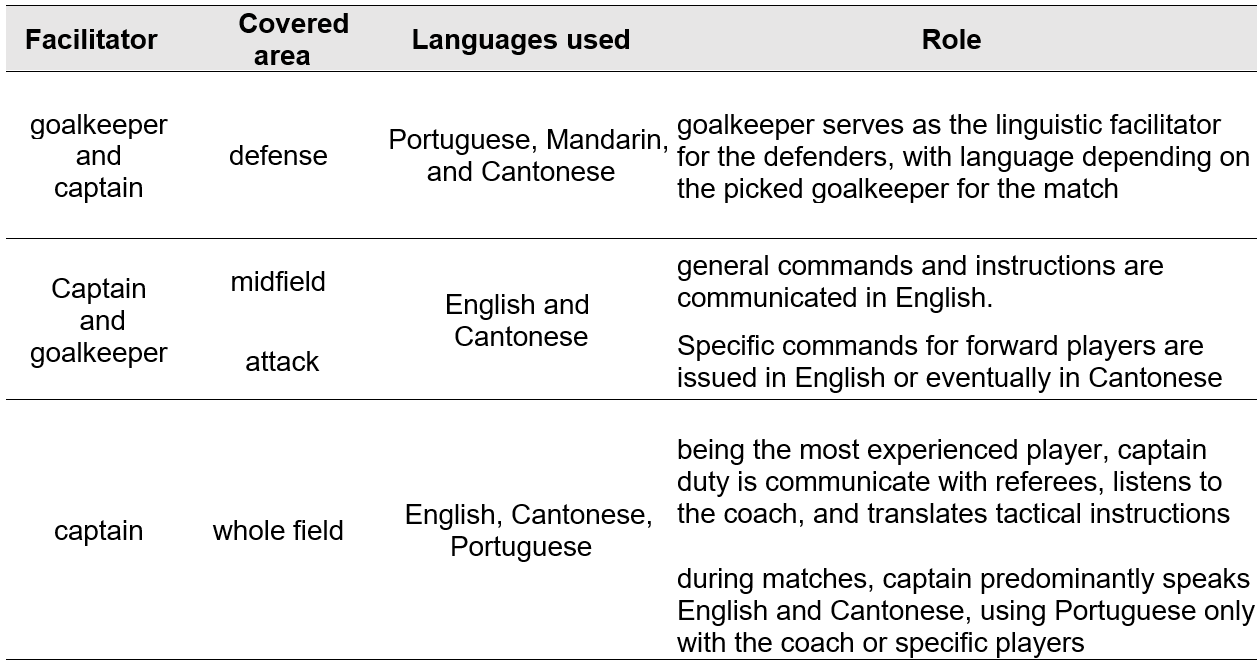

The communicative structure of the team during matches can be summarised in the tables 4 and 5 below, which outline the distribution of languages across tactical roles and the functions of key communicators.

Table 4. Coach commands and communication during matches

Table 5. Facilitators and informal translators’ roles

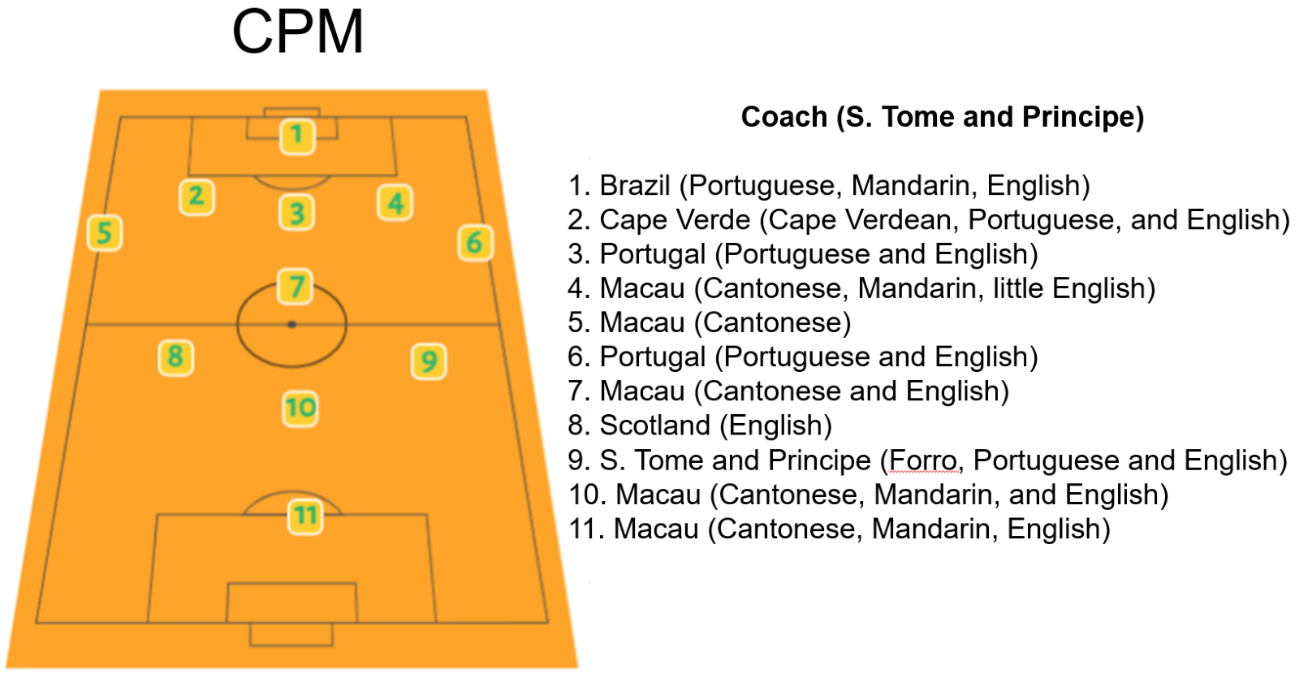

Among the three matches recorded for this study, we analysed the Macau Elite League encounter between the teams Casa de Portugal em Macau (CPM; the analysed team) and Lun Lok (1–3) at the Macau Olympic Stadium – a televised fixture pivotal to CPM’s relegation fight, captured in full through broadcast feeds augmented by locker-room and touchline footage.

Moments before kick-off, P6 delivered a brisk three-minute briefing in simplified English, punctuating each point with emphatic gestures. They unveiled the starting 11 and outlined individual roles, weaving standard English football jargon with Portuguese tactical code (Figures 1–2). When they needed finer distinctions, they slipped into Portuguese; non-Portuguese speaker players simply waited, expecting a relay. That came from P8 – the captain – who summarised the message in Cantonese while retaining the crucial Portuguese and English keywords. Even so, players expressed they felt most secure when instructions were given one-to-one. Using a magnetic tactics board and animated body language, P6 mapped out positional cues; players answered with nods, hand signals and brief murmurs, signalling comprehension. The scene exemplifies intersemiotic translation: meaning negotiated through gesture, space and shared embodied practice rather than language alone (Dusi, 2015).

Figure 1. Starting 11 players and their nationalities and linguist background (created by the authors)

Figure 2. Pre-match briefing (photograph by the authors)

Throughout the season, P8 – the captain and a fluent speaker of Portuguese, Cantonese, and English – served as the squad’s principal informal interpreter in pre-match briefings, seamlessly relaying both team-wide and position-specific directives. In this context, the goalkeepers did not act as linguistic mediators; instead, they were on the receiving end of detailed instructions about defensive positioning.

Vignette 6 – Experiential translation at stoppage (63ʹ, televised feed)

Keeper down; captain waves physio (gesture).

Coach yells in Portuguese: Ataca, ataca! (counterattack)

Keeper stands, shouts Mandarin yào yīshēng! (medical attention), points to chest.

Captain answers Cantonese m̀h yiu (no need), keeper swears Portuguese vai tomar no cu (up yours) and lies down again.

Emotions, languages, and gestures collide, producing a 15-second freeze where meaning hangs on tone and stance more than words.

As tempo rose, verbal economy kicked in: commands shrank to “you go,” “line,” “stay back,” while gestures, eye-contact and tacit routines carried the rest. Only stoppages – usually for injuries – opened a window for longer, layered talk from coaches and informal interpreters. A corner-kick incident (Vignette 6, frames 6–13) illustrates the point. CPM, already 0–1 down, saw their goalkeeper (blue jersey) collide with an opponent (frames 6–7) and concede a goal that was immediately ruled out (frame 8). Sensing a rare tactical timeout, several CPM players exaggerated the keeper’s distress, summoning medical staff and buying the coach a few precious seconds on the touchline.

Frames 6, 7, and 8 (photographs by the authors)

Frames 9, 10, and 11 (photographs by the authors)

Frames 12 and 13 (photographs by the authors)

While the goalkeeper lay prone (frame 9), the captain signalled for treatment, but the coach shouted in Portuguese for everyone to set up a quick counterattack. The goalkeeper struggled to their feet, requested help in Mandarin, tapped their chest, and lay back down when the captain – answering in Cantonese – insisted they were fine (frames 11–12). Exasperated, the goalkeeper snapped “vai tomar no cu” (“up yours”) in Portuguese before dropping to the turf again (frames 12–13). This three-way exchange – Portuguese, Cantonese and Mandarin braided together and super-charged with emotion – shows how language, affect and gesture co-produce meaning in high-pressure moments (Haapaniemi 2024).

The standoff briefly paralysed the team. Unsure whether to follow the coach or hold their shape, Chinese-speaking defenders scanned the referee’s signals and the keeper’s body language; Portuguese-speaking teammates drifted toward the bench. Only when the coach, now furious, repeated the order in English did the squad converge. For an instant the translanguaging “machinery” jammed, and coordination relied on intersemiotic inference – reading distance, posture and referee cues rather than words (Baynham & Lee 2019).

Post-match interviews explain the hesitation by Chinese players in preferring referee gestures over coach commands. On the club’s small bolinha training pitches, the coach’s gestures are visible; in a full-size stadium, noise and distance blur them. Players therefore expect the goalkeeper – who sees and hears both bench and back line – to relay critical instructions. When they were busy sparring with the captain, Chinese defenders defaulted to the referee’s universally legible gestures. Spatial repertoires, then, determine communicative trust: whoever is close enough to be seen, heard and believed becomes the preferred translator (Pennycook & Otsuji 2015).

One defender (P9) captured the cognitive load: “In training I just watch and copy, even if my English is weak. In a match, pressure makes me ‘a bit deaf’ – whatever the language.” Their remark echoes the coach’s earlier warning, channelling Romário’s saying: “the language of training is not the language of the match.” On game day, communication is irreducibly affective, embodied and contingent.

This analysis demonstrates that football’s supposed “universal language” emerges not as a singular code but as a translanguaging ecology in which English, Portuguese, Cantonese, and Mandarin intersect with gesture, space, and embodied cues. While training contexts facilitate the gradual construction of hybrid repertoires, competitive match play exposes the fragility of these communicative networks, as illustrated by the goalkeeper incident where verbal transmission collapsed and players relied instead on referee gestures and spatial alignment. Such moments underscore how high-stakes, time-pressured environments intensify the interdependence of linguistic, gestural, and spatial modalities, thereby challenging essentialist accounts of sports communication and highlighting the adaptive ingenuity of multilingual communities of practice.

5. Discussion and conclusions

This study shows that communication and translation in multilingual sports teams are not merely linguistic; they are embodied, affective, and spatial. On the rink and on the pitch, multimodal translation reorganises access to coordination and authority: who is heard, who bears the communicative labour of translating and relaying, and who gains or loses tactical uptake. In this light, translanguaging in sport is not merely how players communicate; it is how they challenge language hierarchies and claim agency.

We gather these threads under TIE, a lens for studying translation in action. This integrated framework conceptualises translation in team sport as a tri-layered process: (i) the flexible mixing of semiotic repertoires across named languages and modes (translanguaging); (ii) the systematic remapping of meanings between modalities and artefacts, such as speech, gesture, diagrams, spacing, and equipment (intersemiotic translation); and (iii) the affective, embodied negotiation that gives those mappings force in action (experiential translation).

Conceptually, TIE brings together repertoire mixing, cross-modal remapping, and embodied, affective negotiation into a single account of how meaning moves in team sport. Methodologically, we operationalise it through our codebook, vignettes, and a sport-contrast matrix. Analytically, it clarifies how spatial affordances and language hierarchies allocate communicative power and labour. Drawing on TIE, we show that players do not simply translate instructions from one language into another; they move meaning across speech, gesture, bodies, objects, and emotions, crafting hybrid repertoires tuned to each sport’s spatial and affective rhythms. We now develop the discussion in three steps: first, repertoires; second, spatial and temporal affordances; third, power and inclusion.

First, the data make plain that players and coaches in both sports assemble densely multimodal repertoires. On the rink, a Portuguese cue such as “Cruza, tabela, meio” is instantly glossed in Cantonese as “tūng gwo” and embodied in the skating line; on the football pitch a mixed call like “Back four, linha alta (high line!)” travels through English, Portuguese, and Cantonese before the goalkeeper relays it to Chinese full-backs. These moments satisfy the objective of mapping repertoires: they show, in Baynham and Lee’s (2019) sense, how speakers “select from the repertoire” by fusing lexical fragments with gesture, rhythm, and proxemics. The practice is unmistakably translanguaging, yet because the lexical switches trigger immediate bodily realignments it is equally an act of intersemiotic translation.

Second, we examine how each sport’s spatial and temporal affordances, understood as the action possibilities a setting offers to bodies and perception, shape the embodied reworking of coordination and meaning. The contrast is stark. Rink hockey’s enclosed surface compresses communication into millisecond cues: a triple stick tap and a stick point after the captain’s shout of “Costas!” transform a Portuguese warning into a defensive box in a single second. Football, played across a full-size pitch, permits longer verbal routines, but adverse auditory conditions often limit hearing at distance, shifting coordination toward arm signals and captain or goalkeeper relays; in the televised Elite League match the goalkeeper’s groin injury created a moment in which Portuguese orders, Cantonese refusals, and Mandarin pleas overlapped until meaning rested less on words than on tone, stance, and the referee’s hand signals. These scenes support Pennycook and Otsuji’s (2015) claim that spatial repertoires are co-produced by bodies and material layouts, and they show how different settings invite different modes of translation: on the rink, stick taps and gaze at close range; on the pitch, long-range arm signals and captain or goalkeeper relays.

Third, we ask when linguistic plurality becomes a shared asset and when it reproduces dominance. Evidence from both sports confirms the double edge. Code mixing can be tactical – hockey veteran P1 jokes that the hybrid chatter “confuses opponents” – yet Portuguese still indexes prestige and places extra mediating labour on those who command it. Rink hockey makes this especially visible. Portuguese endures as the coaching language not because it maximises mutual intelligibility but because of institutional path dependence: certification routes, federative links, and inherited drill vocabularies anchor Portuguese in training. This helps explain why coaching talk has diversified more slowly than player demographics and why mediating burdens persist, with clear implications for power and inclusion. In football, the trilingual captain and the Portuguese-speaking goalkeeper wield authority partly because they control the languages most valued by coach and referees; their voices carry farther, literally and symbolically. García and Cañado’s (2005) warning that language is never neutral in multicultural teams is borne out: access to communication equals access to power, even as translanguaging allows moments of levelling. The burden of brokerage is also affective: P1 describes the cognitive strain of deciding “whether to use Cantonese, Portuguese, or English” mid-play, and Chinese midfielder P9 admits that pressure makes him “somewhat deaf, no matter the language,” a state that Campbell and Vidal (2024) would call experiential translation under duress.

Throughout, intersemiotic translation remains the hinge between language and movement. Whiteboard arrows become skating drills; a double clap and a finger point condense two Portuguese instructions into a single run; whispered Portuguese and a diagram scratched with a stick convey a coverage shift while a goalkeeper winces on the turf. These examples extend Dusi’s (2015) claim that translation across modes is always dynamic and functional, confirming that on rinks and pitches meaning must be reorganised through speed, spatial awareness, and affective intensity rather than transferred intact. Experiential translation completes this picture, for the most decisive “translations” in both sports occur when feeling and coordination merge, as in the stick-tap celebration that spreads energy through the hockey team or the collective hush that grips footballers while they read the referee’s gesture.

Read through TIE, the evidence shows how meaning travels across speech, gesture, bodies, objects, and emotion under pressure, and how space and language hierarchies sort access and communicative labour. The lens is portable to other multilingual, high-tempo settings and points to simple levers for practice: broaden coaching codes, make nonverbal signalling explicit, and recognise the work of brokers. In short, translation here is not a transfer of text but an ongoing choreography that keeps collective action moving.

References

Adler, P. A., & Adler, P. (1987). Membership roles in field research. Sage.

Aguiar, D., & Queiroz, J. (2013). Semiosis and intersemiotic translation. Semiotica, (196), 283-292. https://doi.org/10.1515/sem-2013-0060

Baynham, M., & Lee, T. K. (2019). Translation and translanguaging. Routledge.

Blackledge, A., & Creese, A. (2017). Translanguaging and the body. International Journal of Multilingualism, 14(3), 250-268. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2017.1315809

Blumczyński, P. (2024). Translating experience, experiencing translationality. Translation Matters, 6(1), 127-144.

Boer, J. (2023). Phenomenology as experiential translation: Towards a semiotic typology of descriptive and expressive ways of making sense of experience. Critical Arts, 39(1–2), 26-44. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2023.2262520

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Butler, J. (1993). Bodies that matter: On the discursive limits of “sex”. Routledge.

Campbell, M., & Vidal, R. (Eds.). (2024). The experience of translation: Materiality and play in experiential translation. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003462538

Canagarajah, S. (2018). Translingual practice as spatial repertoires: Expanding the paradigm beyond structuralist orientations. Applied Linguistics, 39(1), 31-54, https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amx041

Charalambous, P., Charalambous, C., & Zembylas, M. (2016). Troubling translanguaging: Language ideologies, superdiversity, and interethnic conflict. Applied Linguistics Review, 7(3), 327-352. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2016-0014

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Sage.

Deleuze, G., & Parnet, C. (1987). Dialogues. Athlone Press.

DeWalt, K. M., & DeWalt, B. R. (2011). Participant observation: A guide for fieldworkers. Rowman & Littlefield.

Dusi, N. (2015). Intersemiotic translation: Theories, problems, analysis. Semiotica, 2015(206), 181-205. https://doi.org/10.1515/sem-2015-0018

Earley, P. C., & Mosakowski, E. (2000). Creating hybrid team cultures: An empirical test of transnational team functioning. Academy of Management Journal, 43(1), 26-49. https://doi.org/10.5465/1556384

Eco, U. (2000). Experiences in translation. University of Toronto Press.

Esquinca, A., Araujo, B., & de la Piedra, M. T. (2014). Meaning making and translanguaging in a two-way dual-language program on the U.S.-Mexico border. Bilingual Research Journal, 37(2), 164-181. https://doi.org/10.1080/15235882.2014.934970

García, M., & Cañado, M. L. P. (2005). Language and power: Raising awareness of the role of language in multicultural teams. Language and Intercultural Communication, 5(1), 86-104. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708470508668885

García, O., & Otheguy, R. (2020). Plurilingualism and translanguaging: Commonalities and divergences. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 23(1), 17-35. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2019.1598932

García, O., & Wei, L. (2014). Translanguaging: Language, bilingualism, and education. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137385765

Grass, D. (2023). Translation as creative-critical practice. Cambridge University Press.

Haapaniemi, R. (2024). Experientiality of meaning in interlingual translation: The impossibility of representation and the illusion of transfer. In M. Campbell, & R. Vidal (Eds.), The experience of translation: Materiality and play in experiential translation (pp. 21-36). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003462538-3

Hall, E. T. (1966). The hidden dimension. Doubleday.

Hammersley, M., & Atkinson, P. (2019). Ethnography: Principles in practice. Routledge.

ID (Instituto do Desporto do Governo da RAEM) (2004). 36.° Campeonato Mundial B de Hóquei em Patins: Macau sobe ao grupo A, Catalunha ficou de fora. Desporto de Macau, 4. Retrieved September 11, 2025, from https://wttmacao.sport.gov.mo/pt/macaosport/type/show/id/483

Inside FIFA (2020). Tiny Macau eye big gains from down-to-earth development. Retrieved May 22, 2025, from https://inside.fifa.com/news/tiny-macau-eyes-big-gains-from-down-to-earth-development

Jakobson, R. (1959). On linguistic aspects of translation. In R. A. Brower (Ed.), On translation (pp. 232-239). Harvard University Press.

JTM (Jornal Tribuna de Macau) (2013). Macau sem infra-estruturas para futebol profissional. Retrieved June 10, 2025, from https://jtm.com.mo/local/macau-sem-infraestruturas-para-futebol-profissional/

Kendon, A. (2004). Gesture: Visible action as utterance. Cambridge University Press.

Krys, K., Xing, C., Zelenski, J. M., Capaldi, C. A., Lin, Z., & Wojciszke, B. (2017). Punches or punchlines? Honor, face, and dignity cultures encourage different reactions to provocation. Humor, 30(3), 303-322. https://doi.org/10.1515/humor-2016-0087

Lagerström, K., & Andersson, M. (2003). Creating and sharing knowledge within a transnational team: The development of a global business system. Journal of World Business, 38(2), 84-95. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1090-9516(03)00003-8

Lee, T. K. (2022). Translation as experimentalism: Exploring play in poetics. Cambridge University Press.

Li, W. (2011). Moment analysis and translanguaging space: Discursive construction of identities by multilingual Chinese youth in Britain. Journal of Pragmatics, 43(5), 1222-1235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2010.07.035

Li, W. (2018). Translanguaging as a practical theory of language. Applied Linguistics, 39(1), 9-30. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amx039

Massey, D. B. (2005). For space. Sage.

Orellana, M. F., & García-Sánchez, I. (2023). Language brokering and immigrant children's everyday learning in home and community contexts. In H. Pinson, N. Bunar, & D. Devine, Research handbook on migration and education (pp. 173-188). https://doi.org/10.4337/9781839106361.00018

Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods. Sage.

Pennycook, A., & Otsuji, E. (2015). Metrolingualism: Language in the city. Routledge.

Pillow, W. (2003). Confession, catharsis, or cure? Rethinking the uses of reflexivity as methodological power in qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 16(2), 175-196. https://doi.org/10.1080/0951839032000060635

Sabino, R. (2018). Languaging without languages: Beyond metro-, multi-, poly-, pluri- and translanguaging. Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004364592

Scollon, R., & Scollon, S. W. (2004). Nexus analysis: Discourse and the emerging internet. Routledge.

Simon, S. (2019). Translation sites: A field guide. Routledge.

Valero-Garcés, C. (2007). Challenges in multilingual societies: The myth of the invisible interpreter and translator. Across Languages and Cultures, 8(1), 81-101. https://doi.org/10.1556/Acr.8.2007.1.5

Zhu, H., Li, W., & Jankowicz-Pytel, D. (2020). Translanguaging and embodied teaching and learning: Lessons from a multilingual karate club in London. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 23(1), 65-80. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2019.1599811

Data availability statement

The dataset used for this study contains confidential information and is subject to non-disclosure agreements with the participants. Hence, the data are not publicly available.

* ORCID 0000-0002-2291-2399; email: vamaro@mpu.edu.mo↩︎

** ORCID 0000-0001-5669-8119; email: juliojatoba@um.edu.mo↩︎

Notes

Census data (DSEC 2011, 2021) reveal that Portuguese is spoken at home by less than 1% of the population, while Cantonese continues to dominate everyday communication. Available at https://www.dsec.gov.mo/getAttachment/e7db0b5f-452f-47dd-9727-0e209ccb398d/P_CEN_PUB_2011_Y.aspx and https://www.dsec.gov.mo/getAttachment/fda23546-c321-47ae-a5b3-b4a5071cf732/P_CEN_PUB_2021_Y.aspx.↩︎

By the end of March 2025, 27% of Macau’s 687,900 inhabitants were non-resident workers (DSEC, 2025). Although the majority come from Mainland China, a significant portion originates from countries such as the Philippines, Vietnam, Indonesia, Myanmar, and Nepal. Available at https://www.dsec.gov.mo/en-US/Statistic?id=101.↩︎

Throughout this article, ‘representative team’ refers to the senior men’s and senior women’s squads that compete internationally for Macau, China.↩︎

Although played with six or seven players per team, the bolinha (小球, small ball) adopts the rules of 11-a-side football, creating a hybrid format that accommodates spatial constraints while maintaining competitive standards. Eleven-a-side football – or bolão (big ball) – is less common due to the high rent costs and scarcity of full-sized fields, which are generally reserved for the top two professional divisions.↩︎

In order of the number of speakers as a mother tongue: Portuguese (Brazilian, European, and varieties from Africa), Cantonese, English, Mandarin, Cape Verdean Creole, Guinean Creole, Mandarin, Swedish, Italian, and Amharic.↩︎

This saying became popular in Portuguese-speaking countries largely because it was frequently used by Brazilian footballer Romário in response to journalists questioning their absence from training sessions. For Romário, training was merely a physical exercise; they believed that what truly mattered happened during matches, where situations arise spontaneously and must be resolved instantly through a player’s experience and skill. This perspective is common among Brazilian players, who often see the match itself as the space where a player is truly shaped and where one masters the ‘language of football.’↩︎