More than just non-professional translators: The public perception of Chinese fansubbers in an English as a Lingua Franca world

Bin

Gao1, Beijing Foreign Studies

University

Zhourong Shen2, University of International

Business and Economics; Beijing International Studies University

ABSTRACT

This study explores the public perception of Chinese fansubbers in an English as a Lingua Franca (ELF) world. The analysis draws from a survey gathering both quantitative and qualitative data from 327 respondents. In an ELF world, Chinese audiences have demonstrated increasing linguistic competence in their appreciation of fansubbing, which has in turn enhanced their language acquisition. While fansubbers are often seen as amateur translators when compared with their professional counterparts, this study suggests that this distinction, already somewhat blurred within academic discourse, is of little concern to the public. In addition to their role as translators, fansubbers are perceived as cultural brokers and language educators who not only teach but also inspire a new generation of viewers to engage with foreign languages, cultures and translation. The public perception of Chinese fansubbers extends beyond translation quality to include broader and more positive attributes. The findings lead to a new understanding of the social impact of fansubbers.

KEYWORDS

Fansubbing, English as a Lingua Franca, public perception, professionalism, reception.

1. Introduction

Fansubbing has attracted significant attention, both within professional circles and among the general public. Originally denoting a small group of fans translating Japanese cartoons into English, the concept of fansubbing has evolved with globalisation and changing technologies, encompassing a broader range of audiovisual products and geographical areas. To understand the public perception of fansubbing, it is essential to examine the various designations attributed to this practice: fansubbing is termed hive translation (Garcia, 2009), crowdsourcing translation, social translation (O’Hagan, 2009, 2011), volunteer translation (Pym, 2011), collaborative translation (Fernández Costales, 2012) and amateur translation (Izwaini, 2014), among others. Given the heterogenous nature of fansubbing, the term non-professional subtitling translators (Orrego-Carmona, 2019) is used as an umbrella term to contrast with professional translators, who enjoy a recognised level of professionalisation with established norms, roles and identity.

Regardless of the nomenclatures, a few common traits can be ascribed to fansubbers. Fansubbers are driven by ‘either interest or shared values, rather than shared attributes or even shared life experiences’ (Baker, 2009, p. 229). As a self-selected group of volunteer translators, fansubbers create subtitles online for a target audience, to which they belong, without receiving remuneration (Orrego-Carmona & Lee, 2017, p. 2–5). Fansubbers ‘generate and inculcate a sense of community’ and produce subtitles ‘with the aim of sharing and spreading those materials among like-minded people’ (Díaz-Cintas, 2018, p. 130). More often than not, they are individuals without formal training in linguistic mediation. Fansubbers challenge our understanding of the labour structures in the translation industry, ‘as well as the identity and livelihood of translation professionals’ (Pérez-González & Susam-Saraeva, 2012, p. 151). These conventional narratives portray fansubbers as a community of self-selected translators with no formal training, working for free and motivated by shared values and interests. While terms like ‘community and shared interest’ suggest a positive perspective, ‘without formal training’ and ‘working for free’ imply a perception of fansubbers as amateurs.

Research on fansubbers is mostly focused on working norms, product reception and stakeholder evaluation. A prevailing consensus suggests that ‘fansubbers are no longer simply a cheaper alternative to their professional counterparts, and they are as widely established and diversified, if not more so, than professional translation’ (ibid, 2012, p. 152-157). Pérez-González (2007a, p. 76–78) points out that fansubbers’ interventionist tactics, which ‘maximise their own visibility as translators,’ are linked to the convergence of emerging technologies and processes of globalisation. He identifies fansubbing as part of a general move towards viewer empowerment and active modes of consumption resulting from the decentralisation of the media, a phenomenon identified by Turner (2010) as the ‘demotic’ turn. In the age of globalisation and digitalisation, audiences are no longer passive consumers of audiovisual products, but are also turning into active users (Kang & Kim, 2020, p.498). Jenkins et al (2013) argue that those who respond to the needs of their audiences will thrive. Chinese fansubbing communities form an audienceship of mutual affinity, in which the viewers are also would-be-fansubbers (Kung, 2016). To further explore this relationship, Baruch (2021) looks into the motivation and perspectives of a group of volunteers in a fansubbing group, treating them as both fans and co-producers of content. Hu (2014, p. 440) suggests that audiences, being young and technology-savvy, ‘want to transgress national limitations and get in touch with global popular culture.’ The existing literature has explored the characteristics of audiences and their significance. However, there has been little discussions of the public perception of fansubbing.

Researchers often adopt case studies to conduct in-depth examinations of specific fansubbing groups (Wang, 2017; Guo & Evans, 2020; Liu, 2023). However, this approach may overlook the nature of fansubbers as being a diverse community that can vary widely across language pairs and societies. Acknowledging the importance of considering country-specific factors and the potential pitfalls of homogenising fansubbers across societies, this study examines Chinese fansubbers against the backdrop of English as a Lingua Franca (ELF). The aim of this study is to empirically investigate how the public perceives fansubbers in China. It explores both the quality of translation and the roles that fansubbers assume in the eyes of the public through a questionnaire-based survey.

2. Fansubbers’ image explored and unexplored

Fansubbing emerged in China in 2001, coinciding with the country’s accession to the World Trade Organisation and the widespread accessibility of broadband networks. This synchrony with globalisation and technological advancement paralleled China’s rapid economic growth and heightened international interactions. The visibility of fansubbers have increased along with the development of interactive technologies and social platforms (Yin, 2020, p. 12). Fansubbers are regarded as cultural brokers by the public, however, they are discreet about their true identities in order to avoid drawing unwelcome attention to themselves and their organisations (Hsiao, 2014, p. 219). Many of them took the initiative to translate on their own beyond officially recognised channels. Despite copyright protection pressures and official prosecutions, fansubbers have brought foreign audiovisual products into the consumption mix of Chinese audiences (Wang, 2017, p. 185). Operating in the shadows, fansubbers frequently remain reticent concerning their portrayal, particularly when their image becomes a contentious topic. While there is an observable shift in official rhetoric happening in China, it remains uncertain whether their audiences share a similar perspective. As Hill (2019, p. 188) observed, audiences are pathfinders, ‘changing and refiguring their affective, temporal and geographical relations with media.’

2.1. A quality-centred debate

The central point of contention on fansubbing revolves around translation quality, a crucial factor in shaping stakeholders’ perceptions of fansubbers. Professional assessments of translation quality often yield a mixed consensus. The quality of fansubbing ‘circulating on the internet is very often below par,’ although on occasion some fansubs equal the quality of professional translations (Díaz-Cintas & Muñoz Sánchez, 2006, p. 46). Although improvements in terms of quality have been demonstrated (cf. Dwyer, 2017, p. 164–185), it remains a topic of concern in debates on fansubbing. This scepticism towards fansubbing reflects a negative reading on the quality of fansubbers’ work and their image.

The concept of quality is, however, multifaceted, with varied perspectives and contrasting standards. In the industry, quality has been mainly viewed from the angle of process rather than the product (Pedersen, 2017, p. 211). In academia, quality is often evaluated from a ‘non-normative perspective of linguistics and intercultural communication,’ concentrating on equivalence (Szarkowska et al., 2021, p. 663). However, equivalence-based evaluation could prove to be challenging in determining the quality of subtitling, as ‘subjectivity plays a significant role in the equation’ (ibid, 2021, p. 667). It is this lack of stable quality standards that accounts for fansubbers’ impetus and subversive potential. This uncontrollability explains both their power and appeal, and ‘enables a greater proliferation of translation options, resulting in better and faster subs’ (Dwyer, 2012, p. 237). The authenticity of fansubbers’ ‘emerges through the concept of agency and the empowering potential of translation as both a community-building device and mode of personal expression’ (ibid, 2012, p. 238).

Audiovisual translation, whether fan-based or not, is a means rather an end for audiovisual products to be consumed by audiences. To a certain extent, therefore, viewers are the most appropriate judges on translation quality even though their evaluations are more likely to be shaped by subjective impressions rather than established standards, such as accuracy and coherence. The users of the translations are in a privileged position, as ‘they do not only have the option to judge the translations but also have the possibility to compare them against other translations available’ (Orrego-Carmona, 2019, p. 12). Audiences’ perception of quality tends to be relatively positive. For example, by comparing the practices of Chinese official subtitles and fansubs, Kim & Cui (2015, p. 251) find that most viewers believe ‘fansubs are more loyal and authentic to the original works than the official subtitles.’ In a similar vein, another comparison reveals that ‘fansubbers tend to produce subtitles in a highly aesthetic, functional, and semiotically coherent way’ (Lu & Lu 2021, p. 639). However, to present a well-balanced depiction of fansubbers, the discussion needs to extend beyond quality, as it constitutes only a fragment of the broader conversation concerning professionalism.

2.2. A blurred line between amateurism and professionalism

The terms ‘professional’ and ‘non-professional’ have been used quite loosely in academia to distinguish between individuals who are inside the profession and those who are not, such as fansubbers (Jääskeläinen et al., 2011, p. 145). The perception of fansubbers, both within the industry and in the eyes of the public, is often associated with their amateur status, as evidenced by the various labels employed to underscore their non-professional nature. Amateurism, in itself, suggests a lower level of translation quality and a practice that does not warrant serious consideration. However, professionalism is not limited to a person’s capacity to produce target texts, it should also include the translator’s ‘professional status, behaviour of the translator at and outside work, the translator’s adherence to ethical practice principles, professional identity and pride’ (Liu, 2021, p. 2).

Amateur translators, who are generally more inclined to subvert conventions (Wongseree, 2020, p. 540), challenge traditional AVT methods and norms, provoking a significant impact on viewing habits and distribution (Díaz-Cintas & Muñoz Sánchez, 2006; Massidda, 2015). Pérez-González (2007b, p. 260–264) points out that compared to professional subtitlers who ‘appear to be trapped by subtitling standards attuned to the interests of commercial products,’ fansubbers can provide audiences with the ‘fullest and most authentic experience,’ and the subtitling strategies developed for this purpose differ from their mainstream counterparts. In light of fansubbers’ success with audiences, researchers have begun to contemplate the integration of fansubbing into professional translation practice. Seeing fansubbers as a threat that can compete with professional translators, Izwaini (2014, p. 109) argues ‘professionals need to see how they can fit into translation projects in order to lead the process, rather than allow amateurs to take their places.’

However, the demarcation between professional and amateur translators is becoming increasingly blurred, with more similarities emerging than differences. Barra (2009, p. 522) notes the ongoing ‘ties and mirroring between professional and amateur adaptations’ as fans experience a ‘constant professionalisation’ and commercial AVT also borrows from the amateurs. Commonalities are also evident in terms of identity and pride. Both professional and amateur subtitlers exhibit a shared passion and motivation for their work and value their contributions. Professional subtitlers have managed to turn their passion into a profession, seeking to make a livelihood from it, and they often lament the perceived lack of creativity and intellectual engagement in their work. Fansubbers do not profit from their work and ‘see themselves as heroes who are giving their time and effort for a cause’ (Dore & Petrucci, 2021, p. 8). When considering more clear-cut criteria on professionalism in terms of formal training and remuneration, Jääskeläinen et al (2011, p. 147) point out that there are also ‘untrained or self-taught translators who possess all of the qualities of a ‘professional’: livelihood, quality and ethics.’ Given this reality, Dwyer (2012, p. 225) raises a piercing question: ‘if fansubbers were to profit from their labour, would they still be classified as amateur simply on the grounds that most have received no formal translation training?’ This underscores that formal training alone is insufficient to differentiate professionals from amateurs. Antonini et al. (2017, p. 15) note ‘the experience of translation is more important than formal education in providing the kind of training that fosters the transition towards professionalism.’

Translation studies ‘would do well to learn from the interlingual activities of non-professionals,’ and they should not be obsessed with controlling or focusing ‘excessively on the quality of output and/or perceived loss of status by translators’ (Pérez-González & Susam-Saraeva, 2012, p. 158). This can already be observed in the Chinese context. Chinese fansubbers ‘blur the traditional distinction between professional and amateur subtitling,’ and ‘enjoy an unlimited degree of latitude from mainstream subtitling’ in their ‘specific language practices as both fans and translators’ (Lee, 2019, p. 365). Chinese fansubbers are generally well-organised in their work, with a mechanism in place that involves translators, reviewers, copy-editors and uploaders. There is also a selection and probation process for new recruits, whose work will be reviewed by experienced translators and managers to ensure quality (Lu, 2013, p. 56). They assemble ‘to not only participate in the networked production of fansubs but also strive to build a consistent, iconic and unified identity of their group as a subtitling agent’ (Wang, 2017, p. 166). While existing research recognises that fansubbers are no less ‘professional’ than professional translators, it tends to focus on translation quality, working mode, application and impact on culture and industry. Few studies have discussed how Chinese fansubbers are perceived by the public. Public perception can be influenced by numerous factors, one of which, though compelling, is often overlooked – the social backdrop of China since 2001, a period marked by deepening globalisation, with English emerging as a lingua franca in the world.

2.3. An ELF world and its implications

In the 21st century, English has become a global lingua franca, which is to be regarded as ‘a flexible communicative means interacting with other languages and integrated into a larger framework of multilingualism’ (Hülmbauer et al., 2008, p. 25). However, the professional translation industry has, to a great extent, ignored its implications (Campell, 2005, p. 27). This trend has also affected translation studies (Agost, 2015, p. 249), and there is a clear need for translation theory to recognise the changes in the market and explore its realities (Hewson, 2013, p. 275). The effect of ELF has not been much discussed by research in subtitling, but already felt in practice. Audiovisual products are mostly translated between people’s local languages and English, resulting in both professional and amateur subtitlers, as well as viewers, becoming more proficient in English (cf. Lakarnchua, 2017). These developments have certainly introduced new dynamics to the audiovisual translation ecosystem.

Fansubbers are essentially competent bilinguals, and are only referred to as amateurs when compared with professionals. The word ‘professionalism’ indicates professional status, which does not necessarily equate with expert-level skills. In contrast, ‘expert’ implies advanced level of skills and knowledge (Sirén & Hakkarainen, 2002, p. 80). Inexperienced bilinguals can also realise high-level expertise when handling translation tasks that in need of unconventional mediation approaches (Jääskeläinen, 2010, p. 214). The increasing proficiency in English among fansubbers further blurs these distinctions (cf. Hu, 2013).

In an ELF world, viewers may possess at least some degree of proficiency in English. They are now able to compare the subtitles against the original dialogues. Thus, a risk exists as ‘viewers with limited knowledge of English’ will judge translation and assume that ‘a good-quality subtitle might be the one that follows the original’ (Orrego-Carmona, 2019, p. 12). The word ‘might’ suggests a speculative interpretation that requires substantiation. Enhanced English proficiency would undoubtedly influence how viewers assess translations and, by extension, the perception of translators. To understand how the public perceives fansubbers, the impact of ELF cannot be disregarded.

3. Research design

To explore how the public perceives fansubbers in terms of their translation quality, role, professionalism, and contribution to cross-cultural communication and foreign language learning, we conducted a self-administered online questionnaire in Jan. 2021, following the news of the arrest of China’s most prominent fansub group’s operators for copyright infringement (Zhen, 2021). We employed a non-probability convenience sampling and snowball sampling approach, facilitated by link-sharing on the instant messaging mobile app, Wechat, to collect data in a timely manner in response to the arrest, aiming to add relevance and potential for capturing diverse opinions. The survey was conducted in Chinese.

In this survey, the first part is about the demographic information. The second part is to understand the respondents’ perception of fansubbers using a five-point Likert scale, with 1 indicating strong disagreement and 5 indicating strong agreement. This section comprises 16 questions grouped into four dimensions: overall impressions, quality and professionalism, cross-cultural communication, and foreign language learning and career motivation. The third part is an open-ended question that encourages respondents to provide any comments or viewpoints they may have on fansubbers.

We tested the survey for reliability and validity, and obtained a satisfactory Cronbach α of .884. Additionally, an exploratory factor analysis revealed a Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) score of .902 and a Bartlett’s test of sphericity value of .000, meeting the prerequisites for a confirmatory factor analysis. A Structural Equation Model was constructed using AMOS, generating fitting coefficients, as presented in Table 1, which support the questionnaire’s strong validity.

| x2/df | RMSEA | GFI | AGFI | CFI | IFI | TLI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.587 | .070 | .901 | .869 | .916 | .917 | .902 |

Table 1. Fitting Coefficient Table

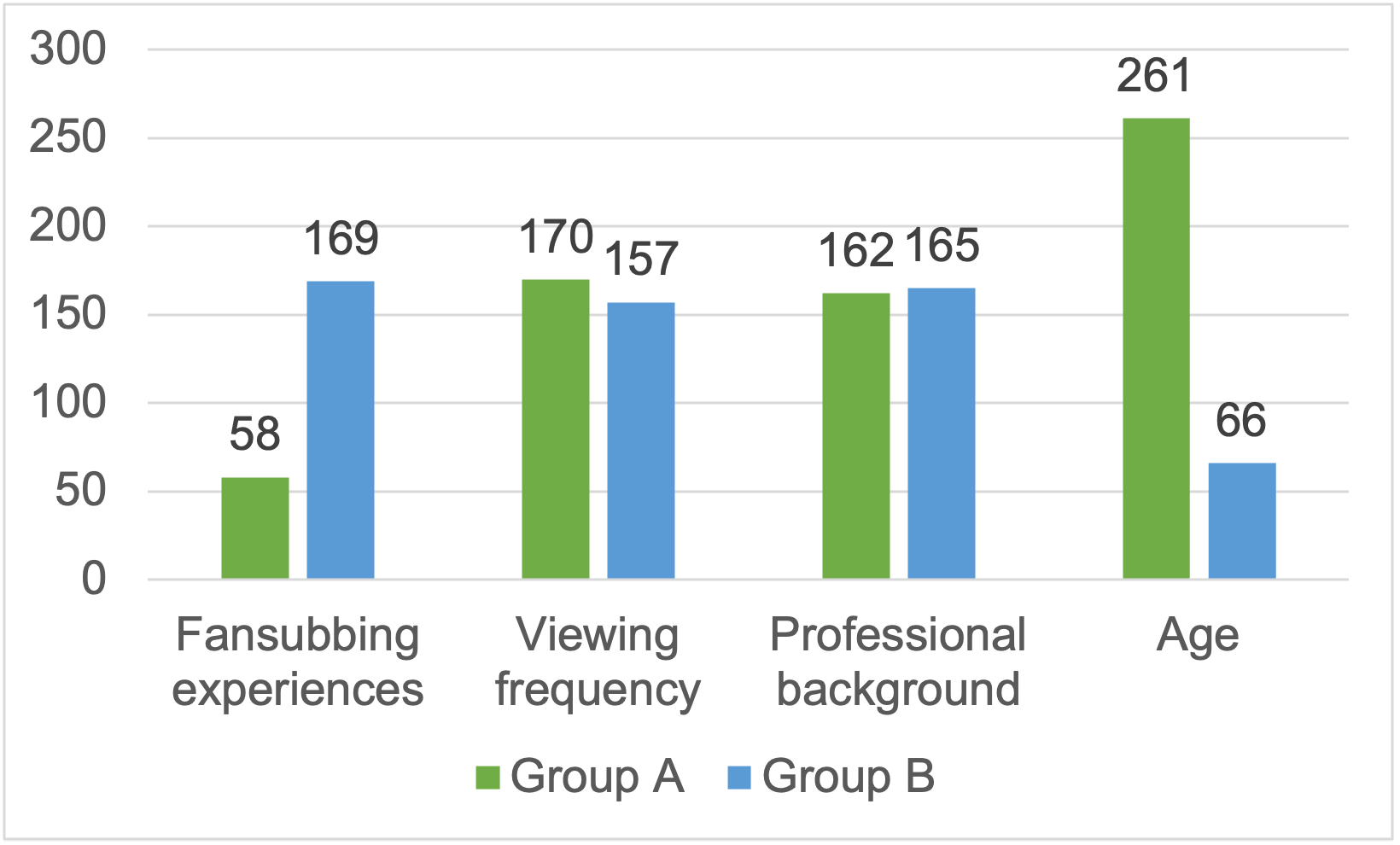

A total of 327 completed and valid questionnaires were collected and analysed. The respondents are categorised by four criteria — with/without fansubbing experiences, viewing frequency, professional background and age. Those who watch fansubbed videos once or twice a week or less are grouped as ‘non-frequent viewers’ and those who watch more than three times a week are grouped as ‘frequent viewers.’ Respondents who identify themselves as ‘students (language majors)’ and ‘language/translation professionals’ are counted as ‘language professionals,’ ‘Students (non-language majors),’ ‘professionals of non-language industries’ and ‘retired/unemployed’ are considered as ‘non-language professionals.’ Viewers are also divided by age into ‘under 30’ and ‘over 30.’ An Independent-Samples T-Test is conducted over these four categories with SPSS 25.

4. Results and discussion

Out of the 327 respondents, 17.7% (n = 58) were once fansubbers. And 53.8% (n = 269) indicate they would notice the specific fansub group responsible for the videos they are watching. This shows a certain level of familiarity with fansubbing within the respondents, which can be further supported by viewing frequency. Although the present study distinguishes ‘non-frequent viewers’ (n = 157, 48%) and ‘frequent viewers’ (n = 170, 52%), the former still watch fansubbed videos once or twice a week; and almost half of frequent viewers watch them on a daily basis. The types of fansubbed videos most frequently watched are as follows: American and European TV Series/movies (n = 309, 94.5%), Japanese/Korean/Thai TV series/movies (n = 179, 54.7%), variety & entertainment shows (n = 125, 38.2%), music videos (n = 61, 18.7%), video games/e-sports (n = 25, 7.6%) and sport events (n = 23, 7.0%). A few respondents also mentioned short video clips, documentaries and celebrity interviews. The result shows that a significant number of fansubbed videos consumed in China are from English-language sources.

In terms of professional background, 49.5% (n = 162) are language professionals and 50.5% (n = 165) are non-language professionals. Around 80% (n = 262) of the respondents are under the age of 30, with half falling within the range of 18 to 24. Around 70% (n = 46) of the remaining respondents are between 31 and 40. This demographic data indicates that the public is generally young. The period of fansub groups’ rapid growth in China, from 2001 to date, coincided with the formative years of the majority of respondents (those under 30) or their early adulthood (those over 30). For data presentation, we classify respondents with ‘fansubbing experiences,’ ‘frequent viewers,’ ‘language professionals’ and ‘people under 30’ into Group A, while their counterparts are grouped into Group B. This categorisation allows for a more focused examination of the data.

Figure 1. Distribution of respondents by categories

4.1. Fansubbers as qualified translators

The quality of fansubbing plays a pivotal role in shaping the public perception of fansubbers in terms of professionalism and overall impression. The respondents have a positive rating on fansubbers’ translation quality (M = 3.5) and image (M = 4.1). The score for fansubbers’ image is higher than that for their translations, suggesting that fansubbers are valued for more than just their translation skills. Before delving into the impact of this difference, it is necessary to analyse the discrepancy in attitudes towards quality between Groups A and B.

| Items | Mean | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Group A | Group B | Overall | |

| If there is more than one subtitle option, I would choose to watch a video because of a particular fansub group. | 3.7 | 3.5 | 3.6 |

| I think fansubbing is better than other translations I encountered elsewhere. | 3.6 | 3.7 | 3.7 |

| Even if fansubbing is sometimes not faithful to the original, I still think it is a good translation. | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.2 |

| I’m willing to hire a fansubber to translate for me/my company for regular translation jobs. | 3.5 | 3.0 | 3.2 |

| I don’t think fansubbing and similar work can be replaced by artificial intelligence. | 4.2 | 3.9 | 4.0 |

Table 2. Public perceptions of the quality of fansubbing

Although it is assumed that Group A might hold a more positive perception due to young age and closer engagement with fansubbing, the analysis does not reveal any significant difference between the two groups. The only exception is that Frequent viewers (M = 3.7) have a more positive perception of fansubbing than infrequent viewers (M = 3.4), with a statistically significant difference (t(325) = -4.012, p < .001). Frequent viewers are more likely to select fansubbers’ works based on quality and personal preference, suggesting that their extensive exposure to fansubbed content influences their perception.

Most respondents express that the quality of fansubbing is superior to other translations they have encountered elsewhere. Notably, non-language professionals (M = 3.8) give a higher rating than language professionals (M = 3.5), with a significant difference (t(325) = -4.012, p = .013). But language professionals still have a positive perception of fansubbing, even though their education and profession make them more likely to encounter high-quality translations. Interestingly, non-language professionals (M = 3.0) are less likely than language professionals (M = 3.5) to consider hiring fansubbers for personal translation tasks, with a statistically significant difference (t(325) = 2.492, p = .013). This may be linked to differences in their familiarity with translation practice and their trust in professionals for such tasks.

The professional status of fansubbers could be the reason why there exists a seemingly contradictory attitude toward the hiring of fansubbers. In China, there is a widespread belief that officially accredited professional services are more reliable and trustworthy. Consequently, the public tends to feel more comfortable turning to professional translators, even though they acknowledge that fansubbers may produce better translations. In addition, fansubbers may not be available for the public to hire. This finding contrasts with the conclusion that ‘translators are undervalued and translator professionalism is overlooked’ as general public ‘misconceive of translation as an innate ability’ (Liu, 2021, p. 13). Language professionals, who are presumably more competent in evaluating translation quality, seem to be more willing to hire fansubbers, irrespective of their non-professional status. For language professionals, the ability to deliver high-quality translations is more important than having a professional status, certification, or accreditation.

The overall positive impression of fansubbing quality raises the question of whether categorising fansubbers as non-professional translators is still relevant. When considering the criteria of professionalism, fansubbers have demonstrated a commitment to ethical practice, professional identity and pride. Barra (2009, p. 521) asserts the distribution of labour amongst fansub groups reaches ‘a semi-professional level of specialisation and organisation.’ Fansub groups have ‘proven themselves able to support highly developed codes of ethics, they also regularly produce members and spin off groups that refuse to play by the rules’ (Dwyer, 2012, p. 237). The quality standards of fansubbing are no less stringent than those of their professional counterparts. Fansubbers not only invest time and effort in improving their translation skills while they work, but also cultivate their teamwork spirit, ‘as they are required to meet skill qualifications’ (Kim & Cui, 2015, p. 262). When quality, which has been a focal point of contention, is removed from the equation, it appears that the primary distinguishing factors between professional and non-professional translators are whether or not they have received formal training (assuming that on-the-job training for fansubbers is not considered proper training) and whether or not they work for free. From a practical standpoint, these two criteria may be more relevant to academia for research purposes than they are to viewers. This suggests that viewers perceive quality and effectiveness of translation services as more important than formal training or professional status.

Chinese Fansubbers are also known for their 神翻译 ‘shén fān yì, zinger translation,’ which denotes a type of translation that combines transliteration and free translation, resulting in effects that can be brilliant, comical, or even ridiculous. Zinger translation is controversial because its creativity often comes at the expense of fidelity. To appreciate zinger translation, the audiences need to be at least somewhat bilingual. The respondents are educated enough to realise that fidelity is more important in translation. Nevertheless, their responses reflect a mean of 3.15 when asked if a translation can be considered as a good or zinger translation even if it deviates significantly from the original meaning. This suggests an overall neutral position, although 43.1% (n = 141) of respondents still choose ‘agree’ and ‘strongly agree’ on this question. However, zinger translation could be one of the reasons why respondents think that fansubbing cannot be replaced by artificial intelligence (M = 4.0). This viewpoint has been corroborated by the comment of respondent No.165:

To tell the truth, fansubbers who ‘translate to spread love’ can be much better translators than the ones I pay for when I need translation services. Their labour of love is done out of passion and enthusiasm for the language. It is not uncommon for an entire fansub group to spend two days searching and discussing the most appropriate translation for an ambiguous phrase. This kind of love is different from the paychecks and deadlines in a translation company. The work of fansubbers is irreplaceable. It’s hard work, and it’s very meaningful. (translated from Chinese)

It can be concluded that the respondents hold a positive opinion of fansubbing quality. This positive attitude is also reflected in their perceptions of fansub groups in general, as shown in Table 3.

| Items | Mean | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Group A | Group B | Overall | |

| I have negative impressions of fansub groups. (reversed in statistics) | 4.4 | 4.2 | 4.3 |

| The image of fansub groups is positive in my mind. | 4.4 | 4.3 | 4.4 |

| Fansub groups made me respect translators in general. | 4.2 | 4.2 | 4.2 |

| I’d like to continue watching fansubbed videos, even if it costs extra. | 3.6 | 3.3 | 3.5 |

Table 3. Public perceptions of fansub groups in general

More than 85.63% (n = 280) of the respondents maintain a positive perception of fansubbers, regardless of whether they have been fansubbers or not. A common impression was that fansubbers are only popular because they provide audiovisual products for free. Therefore, for the Chinese audiences accustomed to ‘free meals,’ it is next to impossible for them to pay for subtitles (Kangsitanding, 2016). According to the survey, almost half of the respondents (n = 162, 49.51%) expressed their willingness to pay for fansubbing if a fee was required. Additionally, 30.89% (n = 101) of the respondents believe that whether or not a fee is charged has no impact on their intention to watch fansubbed videos. While this finding does not necessarily translate into actual behaviour, as respondents may act differently if a service fee is actually charged, the result does challenge the assumption that they only applaud fansubbers for the ‘free meals.’

Even though fansubbing and professional translation may involve different levels of expertise, quality requirements and ethical considerations (cf. Davis & Yeh, 2017), the public generally holds a favourable impression of fansubbing, and by extension, professional translation. A total of 77.37% (n = 253) of respondents admit that they respect translators in general because of fansubbers. Non-language professionals (M = 4.3) are significantly more inclined to do so than language professionals (M = 4.0) (t(325) = -2.31, p = .021). This could be attributed to the fact that non-language professionals rely more on the subtitles to understand audiovisual content, and thus form a stronger bond with fansubbers.

Compared to language professionals who have a deeper understanding of the translation ecosystem, non-language professionals rely, to some extent, on fansubbers to understand the translation industry, even though this understanding may only represent a small portion of the bigger picture. In this regard, fansubbers inadvertently contribute to the professionalisation of translators by fostering respect for them among the public. In addition to quality, there are more reasons to account for the positive evaluation of fansubbers. The questionnaire further reveals that the role fansubbers play in cross-cultural communication and language education are also factors contributing to a positive public perception.

4.2. Fansubbers as cultural brokers

In the early 21st century, English has undoubtedly become the lingua franca that allows the different languages, cultures and countries to interface more easily (cf. Anderman & Rogers, 2005). The purpose and motivation behind fansubbing are ‘to make a contribution in an area of particular interest and make it accessible to a broader range of viewers, who belong to different linguistic communities’ (Bogucki, 2009, p. 49). The widespread use of English has facilitated the works of fansubbers and has made it easier for viewers to appreciate their work. The growth of Chinese fansubbers and the increasing interest of the Chinese audiences in foreign cultures have mutually reinforced each other in the context of ELF.

Audiovisual products play a key role in introducing foreign cultures to some respondents. They are a major, if not the only, channel for cultural exposure. Given this context, a professor from Fudan University argued that the influence and significance of fansubbing are comparable to three major translation activities in Chinese history. These include the translation of Buddhist scriptures by Hsuan Tsang in the Tang Dynasty, the translation of Western cultures by translators like Yan Fu and Lin Shu in Modern China, and the translation of world modern humanities classics by publishers like Joint Publishing (Sanlian Press) and the Commercial Press (Yan, 2019). To assess the public perception of fansubbing in terms of its role in cross-cultural communication, the questionnaire included this statement for respondents to consider.

| Items | Mean | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Group A | Group B | Overall | |

| Fansubbing’s influence on Chinese translation is equivalent to three major translation activities in the Chinese history, i.e., the translation of Buddhist scriptures by Hsuan Tsang in the Tang Dynasty, the translation of Western cultures by Yan Fu, Lin Shu among other translators in Modern China, and the translation of world modern humanities classics by Joint Publishing (Sanlian Press) and the Commercial Press. | 3.6 | 3.5 | 3.5 |

| Fansub groups played an irreplaceable role in helping me learn about foreign cultures. | 4.0 | 3.9 | 4.0 |

| Even though I can understand audiovisual products without subtitles, I’d still watch fansubbing for a better viewing experience. | 3.8 | 3.6 | 3.7 |

Table 4. Public perceptions of fansub groups as cultural brokers

Approximately half of the respondents (n = 161, 49.23%) agreed with this statement, while it may be too early to declare fansubbing as the fourth wave of large-scale translation activity in Chinese history without a longitudinal perspective. The other half approached this recognition with caution but acknowledged the irreplaceable role of fansubbers in providing access to foreign cultures. This recognition is even more significant among frequent viewers (M = 4.1, t(325) = -2.71, p = .007) and viewers under 30 (M = 4.0), compared to infrequent viewers (M = 3.8) and viewers over 30 (M = 3.7). It is unclear whether frequent viewers watch more fansubbed videos because they value fansubbing in general or because they have a stronger incentive to learn about other cultures. However, the result shows frequent viewers would still choose to watch fansubbed videos even if they do not need the help of subtitles, indicating an appreciation of fansubbing as an art that enhances the viewing experience, implying at least some bilingual competence.

Recognising that audiences are becoming more bilingual, fansubbers have become more experimental with their translation strategies to enhance the viewing experience through linguistic transfer. ELF has been applied as the accommodation strategy by fansubbers, leaving the headnotes or comments as a supplement for their ‘non-native’ and ‘translocally located’ audience who are from different geographical locations yet consuming the same audiovisual product (Lee, 2019, p. 366). These notes help viewers to quickly understand cultural concepts that would otherwise require extensive research. Audiences watch fansubbed videos not only to access foreign audiovisual products but also to appreciate the translation and enrich their foreign cultural literacy. This is particularly evident among younger audiences and language professionals who are already self-motivated to learn about foreign cultures. Non-language professionals (M = 4.1, t(325) = -1.98, p = .048) are more likely than language professionals (M = 3.8) to acknowledge that fansub groups are irreplaceable for them to access foreign cultures. The more viewers want to know about foreign cultures, the more likely they are to watch fansubbed videos, with frequent viewers (M = 3.9, t(313) = -3.029, p = .003) showing greater appreciation for fansubbers in this regard than infrequent viewers (M = 3.6).

Fansubbers are more likely to innovate, to play with the material at hand, and to retell it in a way that is likely to be more interesting and intelligible to their audiences – often because they are themselves part of the audiences. This strengthens ‘their sense of initiative, authority and agency’ (Pérez-González & Susam-Saraeva, 2012, p. 158). In the past, Chinese fansubbers have often operated inconspicuously. However, their contribution extends beyond mere translation, and plays a significant role in facilitating cross-cultural communication. As respondents 143 and 146 put it: “Fansubbers are porters of culture who work out of passion; competent fansubbers are paragons for cultural input and output.” Respondents not only use fansubbers’ translations to gain deeper insights into foreign cultures but also to improve their language skills. In a way, fansubbers play an indispensable role in supporting foreign language education for specific group of audiences.

4.3. Fansubbers as language educators

ELF is considered to be a fansubbing strategy (Lee, 2019), and fansubbers, in turn, may be facilitating the spread of ELF as a phenomenon. The following questions, which are included in the questionnaire, are designed to find out whether fansubbers and fansubbing contributed to the respondents’ language learning, fuelled their passion for translation, and influenced their career choices.

| Items | Mean | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Group A | Group B | Overall | |

| I once was inspired to join fansub groups or translation industry because of my exposure to some excellent or poor fansubbing. | 3.6 | 2.9 | 3.3 |

| My foreign language skills have improved dramatically by watching fansubbed videos. | 3.4 | 2.9 | 3.1 |

| I once was motivated at some point to become a translator because of watching fansubbed videos. | 3.3 | 2.6 | 2.9 |

| Fansub groups played a role in my career choice. | 3.0 | 2.5 | 2.8 |

Table 5. Public perceptions of fansub groups as language educators

We find marked differences between Group A and Group B across all the four questions in this section. Group A is more inclined to admit that watching fansubbed videos greatly improves their language and translation skills. Moreover, fansubbing, regardless of its quality, is more or less a motivating factor for the respondents to consider joining fansub groups or translation industry at one time or another. Language students can be self-motivated to learn languages and translation, as watching fansubbed videos is more of an aid than the only incentive for them. We find that this view is also held by frequent viewers and respondents with fansubbing experiences.

To avoid a possible research bias in studying only the above groups, we turn to viewers under the age of 30, who may be more inclined to watch fan-subbed audiovisual programmes available for free on the Internet. We found that watching fan-subbed videos had a similar positive impact on their language skills as the other groups. Based on this finding, we argue that fansubbers not only act as language instructors, but also as language educators. They extend their impact beyond language learning by inspiring and motivating their audiences to such an extent that they even influence some viewers’ career choices. The respondents gave an average of 2.8 to the question of whether fansub groups played a role in their choice of career. Although this is the lowest score of all the questions, it is still above 2.5. The influence is much more pronounced among language professionals (M = 3.0) than among non-language professionals (M = 2.5). The identification of a relationship between fansubbing and career choice may seem unexpected, but it is noteworthy that 92 (28%) respondents chose ‘agree’ or ‘strongly agree’ to this question. Not surprisingly, the majority of them are language professionals. However, non-language professionals also acknowledge the role of fansubbers in improving their foreign language skills (M = 2.9) and occasionally motivating them to pursue a career in translation (M = 2.6) or even to become fansubbers themselves (M = 2.9), regardless of their ultimate career choice.

This proves that fansubbing is more than just a means of entertainment or language learning. Some viewers admit that fansub groups played a role in their decision to become translators. Fansubbing groups also motivate and inspire frequent (M = 3.6) and younger viewers (M = 3.4) to become fansubbers or translators at some point. The group of people most influenced by fansub groups are those who used to work as fansubs. Respondent 230 said:

I was a fansubber when I was a graduate student, making friends from all over the country. I remember that the leader of a fansubbing group was a freshman at Beijing No.4 High School whose English ‘easily overwhelmed’ me. And I was a graduate student who had passed the test for English majors, Band 8. I was very impressed. However, my English wouldn’t be as good as it is now without my experience in translating subtitles and working on timelines. And before I went abroad, I learned everything about foreign countries from fansub groups. I can say that the works I did as a subtitle maker have been constantly shaping the way I see the world, think and socialise. Although my work now has nothing to do with foreign languages, I have to say that I wouldn’t be who I am today without fansub groups. (translated from Chinese)

Although many fansubbers, like respondent 230, started their work out of simple interest, they have an unexpected but profound influence, particularly on language professionals and younger people. Fansubbers stimulate the viewer’s enthusiasm in language and translation learning, thereby promoting ELF. Fansubbers also motivate their audiences, albeit primarily through their example rather than persuasion. This kind of encouragement enhances what Hills (2003, p. 60) calls ‘the emotional attachment and passion of fans,’ which has often been taken for granted and not placed centre-stage. Fansubbing has a bigger impact on language professionals, who express an even more positive perception of fansubbers compared to the broader viewership. Many language professionals agree that fansubbers have played a role in shaping their career choices. This suggests that the argument that fansubbers pose a threat to the professional translation field and could undermine its professionalisation needs to be reconsidered.

5. Conclusion

This empirical research aims to present the viewpoint of audiences towards fansubbers. Chinese fansubbers are not fanatics who are ‘obsessed, deviant and dangerous’ as depicted by traditional mass media (Zhang & Mao, 2013, p. 57). This study shows that fansubbers are also very different from their portrayal by academia, which often conveys different perspectives on the translation quality and professional status of fansubbers. Public opinion in China, on the other hand, tends to be positive about the quality of fansubbing. The Chinese public does not see a clear line separating professional translators from their amateur counterparts, nor do they see fansubbers as inherently less qualified translators. This finding raises a number of interesting questions, such as the criteria by which these two categories can be distinguished and their relevance to the professionalisation of translators. Fansubbers, often referred to in academic discourse as non-professional translators, contribute to improving the public perception of the translation profession in general. They inspire viewers to delve deeper into foreign languages and cultures, and help them to realise that translation is a task not easily undertaken by just any bilingual individual.

Another notable finding is the public’s recognition of fansubbers not only as translators but also as cultural brokers and language educators. This perception is partly due to the spread of ELF. The Millennial generation in China are more competent in English (Shen & Gao, 2023, p. 8), and they are more linguistically proficient to appreciate the works of fansub groups. Fansubbers’ work thus enhances the language learning experience of their viewers. In this symbiotic process, fansubbers have inspired and motivated a generation of Chinese to take an interest in foreign cultures and language learning. Some of these younger viewers eventually take up careers as translators, interpreters or language professionals. Even for those who do not pursue careers within the language industry, fansubbing provide a valuable resource for accessing foreign cultures. On some occasions, experiences in fansubbing have had life-changing effects. The public perception of Chinese fansubbers is positive.

The results of this study do not claim to be generalisable, as the non-probability convenience and snowball sampling methods may introduce bias. The overall positive perception of fansubbers could also be due to factors other than quality, such as emotional connections and a sense of community among fansubbing enthusiasts fostered by social media. However, these factors do not negate the important role and impact of fansubbers in the field of translation.

Since little research has been done to explore the public perception of fansubbers in China or elsewhere, this study provides useful insights into understanding fansubbing as an integral part of the translation ecosystem, and may inspire researchers to further explore the social impact of fansubbing on both professional translators and viewers in broader geographical regions. Given the evolving nature of fansubbing and its integration into the cultural industries, public perceptions of fansubbers may also change over time, thus requiring further research.

Acknowledgements/Funding

This research was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for Central Universities [2022JS004], the Beijing Municipal Social Science Funds [21YYB002], and the Beijing International Studies University Research Project [KYZX23A005].

References

Agost, R. (2015). Translation Studies and the mirage of a lingua franca. Perspectives, 23(2), 249–264. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2015.1024695

Anderman, G., & Rogers, M. (Eds.). (2005). In and Out of English: For Better, For Worse. Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781853597893

Antonini, R., Cirillo, L., Rossato, L., & Torresi, I. (Eds.). (2017). Non-professional interpreting and translation: State of the art and future of an emerging field of research. John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Baker, M. (2009). Resisting State Terror: Theorizing Communities of Activist Translators and Interpreters. In E. Bielsa & C. W. Hughes (Eds.), Globalization, Political Violence and Translation (pp. 222–242). Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230235410_12

Barra, L. (2009). The mediation is the message: Italian regionalization of US TV series as co-creational work. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 12(5), 509–525. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367877909337859

Baruch, F. (2021). Transnational Fandom: Creating Alternative Values and New Identities through Digital Labor. Television & New Media, 22(6), 687–702. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476419898553

Bogucki, Ł. (2009). Amateur Subtitling on the Internet. In J. D. Cintas & G. Anderman (Eds.), Audiovisual Translation (pp. 49–57). Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230234581_4

Campell, S. (2005). English Translation and Linguistic Hegemony in the Global Era. In G. Anderman & M. Rogers (Eds.), In and Out of English: For Better, For Worse. Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781853597893

Díaz-Cintas, J. (2018). ‘Subtitling’s a Carnival’: New Practices in Cyberspace. JoSTrans: The Journal of Specialised Translation, 30, 127–149.

Díaz-Cintas, J., & Muñoz Sánchez, P. (2006). Fansubs: Audiovisual Translation in an Amateur Environment. JoSTrans: The Journal of Specialised Translation, 6, 37–52.

Dore, M., & Petrucci, A. (2021). Professional and amateur AVT. The Italian dubbing, subtitling and fansubbing of The Handmaid's Tale. Perspectives, 30(5), 876–897. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2021.1960870

Dwyer, T. (2012). Fansub Dreaming on ViKi: ‘Don’t Just Watch But Help When You Are Free’. The Translator, 18(2), 217–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/13556509.2012.10799509

Dwyer, T. (2017). Speaking in subtitles: Revaluing screen translation. Edinburgh University Press.

Fernández Costales, A. (2012). Collaborative Translation Revisited: Exploring the Rationale and the Motivation for Volunteer Translation. FORUM. Revue Internationale d’interprétation et de Traduction / International Journal of Interpretation and Translation, 10(1), 115–142. https://doi.org/10.1075/forum.10.1.06fer

Garcia, I. (2009). Beyond translation memory: Computers and the professional translator. JoSTrans: The Journal of Specialised Translation, 12, 199–214.

Guo, T., & Evans, J. (2020). Translational and transnational queer fandom in China: The fansubbing of Carol. Feminist Media Studies, 20(4), 515–529. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2020.1754630

Hewson, L. (2013). Is English as a Lingua Franca Translation's Defining Moment? The Interpreter and Translator Trainer, 7(2), 257–277. https://doi.org/10.1080/13556509.2013.10798854

Hill, A. (2019). Media experiences: Engaging with drama and reality television. Routledge.

Hills, M. (2003). Fan Cultures. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203361337

Hsiao, C. (2014). The Moralities of Intellectual Property: Subtitle Groups as Cultural Brokers in China. The Asia Pacific Journal of Anthropology, 15(3), 218–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/14442213.2014.913673

Hu, K. (2013). Chinese subtitle groups and the neoliberal work ethic. In N. Otmazgin & E. Ben-Ari (Eds.), Popular culture, co-productions and collaborations in East and Southeast Asia (pp. 207–232). NUS Press.

Hu, K. (2014). Competition and collaboration: Chinese video websites, subtitle groups, state regulation and market. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 17(5), 437–451. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367877913505170

Hülmbauer, C., Böhringer, H., & Seidlhofer, B. (2008). Introducing English as a lingua franca (ELF): Precursor and partner in intercultural communication.

Izwaini, S. (2014). Amateur translation in Arabic-speaking cyberspace. Perspectives, 22(1), 96–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2012.721378

Jääskeläinen, R. (2010). Are all professionals experts? Definitions of expertise and reinterpretation of research evidence in process studies. In G. M. Shreve & E. Angelone (Eds.), American Translators Association Scholarly Monograph Series: XV (pp. 213–227). John Benjamins Publishing Company. https://doi.org/10.1075/ata.xv.12jaa

Jääskeläinen, R., Kujamäki, P., & Mäkisalo, J. (2011). Towards professionalism — or against it? Dealing with the changing world in translation research and translator education. Across Languages and Cultures, 12(2), 143–156. https://doi.org/10.1556/Acr.12.2011.2.1

Jenkins, H., Ford, S., & Green, J. (2013). Spreadable media: Creating value and meaning in a networked culture. New York University Press.

Kang, J.-H., & Kim, K. H. (2020). Collaborative translation: An instrument for commercial success or neutralizing a feminist message? Perspectives, 28(4), 487–503. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2019.1609534

Kangsitanding. (2016). Fansubbing Groups: Hero or gozilla?. Chinadaily. http://column.chinadaily.com.cn/a/201611/10/WS5bf228fca3101a87ca93ecc9.html. Retrieved 2021-04-21

Kim, G., & Cui, L. (2015). Are Fansubs More Trustworthy than Subtitles in China? -With a Focus on the Movie, The Avengers-. Journal of East Asian Cultures, 61, 251–274. https://doi.org/10.16959/JEACHY.61.201505.251

Kung, S.-W. (2016). Audienceship and community of practice: An exploratory study of Chinese fansubbing communities. Asia Pacific Translation and Intercultural Studies, 3(3), 252–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/23306343.2016.1225329

Lakarnchua, O. (2017). Examining the potential of fansubbing as a language learning activity. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 11(1), 32–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/17501229.2015.1016030

Lee, T. E. (2019). English as a lingua franca (ELF) in Chinese fansubbers’ practices: With reference to Rizzoli & Isles over six seasons. Babel. Revue Internationale de La Traduction / International Journal of Translation, 66(3), 365–380. https://doi.org/10.1075/babel.00108.lee

Liu, C. F. (2021). Translator professionalism in Asia. Perspectives, 29(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2019.1676277

Liu, X. (2023). Fan Translation: A Look into the Chinese Fansubbing Group Beverly Fansub on Bilibili. Journal of Education and Educational Research, 5(1), 401–421.

Lu, S., & Lu, S. (2021). Understanding intervention in fansubbing’ s participatory culture: A multimodal study on Chinese official subtitles and fansubs. Babel. Revue Internationale de La Traduction / International Journal of Translation, 67(5), 620–645. https://doi.org/10.1075/babel.00236.lu

Lu, Y. (2013). Analysis and Comparison on Crowdsourcing translation. Chinese translator's journal, 34(03), 56–61.

Massidda, S. (2015). Audiovisual translation in the digital age: The Italian fansubbing phenomenon. Palgrave Macmillan.

O’Hagan, M. (2009). Evolution of User-generated Translation: Fansubs, Translation Hacking and Crowdsourcing. The Journal of Internationalization and Localization, 94–121. https://doi.org/10.1075/jial.1.04hag

O’Hagan, M. (2011). Community Translation: Translation as a social activity and its possible consequences in the advent of Web 2.0 and beyond. Linguistica Antverpiensia, New Series – Themes in Translation Studies, 10. https://doi.org/10.52034/lanstts.v10i.275

Orrego-Carmona, D. (2019). A holistic approach to non-professional subtitling from a functional quality perspective. Translation Studies, 12(2), 196–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/14781700.2019.1686414

Orrego-Carmona, D., & Lee, Y. (2017). Non-Professional Subtitling. In D. Orrego-Carmona & Y. Lee (Eds.), Non-Professional Subtitling (pp. 1–12). Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Pedersen, J. (2017). The FAR model: Assessing quality in interlingual subtitling. JoSTrans: The Journal of Specialised Translation, 28, 210–229.

Pérez-González, L. (2007a). Fansubbing anime: insights into the ‘butterfly effect’ of globalisation on audiovisual translation. Perspectives, 14(4), 260–277. https://doi.org/10.1080/09076760708669043

Pérez-González, L. (2007b). Intervention in new amateur subtitling cultures: A multimodal account. Linguistica Antverpiensia, New Series – Themes in Translation Studies, 6. https://doi.org/10.52034/lanstts.v6i.180

Pérez-González, L., & Susam-Saraeva, Ş. (2012). Non-professionals Translating and Interpreting: Participatory and Engaged Perspectives. The Translator, 18(2), 149–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/13556509.2012.10799506

Pym, A. (2011). Translation research terms: A tentative glossary for moments of perplexity and dispute. In A. Pym (Eds.), Translation Research Projects 3 (pp. 26). Intercultural Studies Group.

Shen, Z., & Gao, B. (2023). Public Perceptions of Diplomatic Interpreters in China: A Corpus-driven Approach. International Journal of Chinese and English Translation & Interpreting, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.56395/ijceti.v2i1.60

Sirén, S., & Hakkarainen, K. (2002). Expertise in Translation. Across Languages and Cultures, 3(1), 71–82. https://doi.org/10.1556/Acr.3.2002.1.5

Szarkowska, A., Díaz Cintas, J., & Gerber-Morón, O. (2021). Quality is in the eye of the stakeholders: What do professional subtitlers and viewers think about subtitling? Universal Access in the Information Society, 20(4), 661–675. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10209-020-00739-2

Turner, G. (2010). Ordinary people and the media: The demotic turn. SAGE.

Wang, D. (2017). Fansubbing in China—With Reference to the Fansubbing Group YYeTs. JoSTrans: The Journal of Specialised Translation, 28, 165–190.

Wongseree, T. (2020). Understanding Thai fansubbing practices in the digital era: A network of fans and online technologies in fansubbing communities. Perspectives, 28(4), 539–553. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2019.1639779

Yan, F. (2019). Dialogue: the rise of fansubbing and the dusk of dubbing. Sohu. https://www.sohu.com/a/314823667_260616. Retrieved 2021-04-21

Yin, Y. (2020). An emergent algorithmic culture: The data-ization of online fandom in China. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 23(4), 475–492. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367877920908269

Zhang, W., & Mao, C. (2013). Fan activism sustained and challenged: Participatory culture in Chinese online translation communities. Chinese Journal of Communication, 6(1), 45–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/17544750.2013.753499

Zhen, B. (2021). YYeTs smacked down for 16-million-worth of copyright infringements! 14 detained. Sohu. https://www.sohu.com/a/448516172_120490186. Retrieved 2021-04-21

Data availability statement

The data was uploaded to Science Data Bank. https://cstr.cn/31253.11.sciencedb.15769. https://doi.org/10.57760/sciencedb.15769

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).