Exploring the interface between corpus and statistical modelling: a multi-methodological analysis of lexical variation in Islamic legal discourse

Rana Roshdy*,1Dublin City University

ABSTRACT

This research sets out to investigate how ‘culture-specific’ or ‘signature’ concepts are rendered in English-language discourse on Islamic, or ‘shariʿa law. Islamic jurisprudence is born from the fusion of Islamic scriptures and Arabic culture; therefore, it provides ample room for accommodating a distinctive legal diction that is both culture-bound and system-bound. Accordingly, the expression of shariʿa law in English would fall under the paradigm of intersystemic translation, which occurs upon the mediation between two legal systems and poses the challenge of incongruity of legal terminology. This study is based on the self-built Islamic Law Corpus (ILC), a 9-million-word monolingual English corpus, covering diverse genres on Islamic finance and family law. Using the power of corpus-processing and statistical regression software (Sketch Engine & MATLAB), this research presents a multi-methodological, multifactorial, and interdisciplinary approach to investigate lexical variation in expressing cultural phenomena within Islamic legal discourse. The analysis confirms that the contextual factors (‘genre’, ‘function’, and ‘subject field’) do influence the choice of an Arabic loanword versus English alternatives.

KEYWORDS

Corpus linguistics, genre variation, profile-based correspondence analysis, logistic regression, Islamic law and finance.

1. Introduction

This article reports on an empirical study that adopts a “multi-methodological, multifactorial, interdisciplinary approach”, in line with the “updated research agenda for CBTS” (corpus-based translation studies), as proposed by De Sutter and Lefer (2020, p. 6). Calling for an interdisciplinary approach to translation, De Sutter and Lefer suggest using the term ‘empirical translation studies’ for corpus-based translation research which adopt multi-methodological designs. By way of definition, a multi-methodological design is based on “[t]he cross-fertilization of different methodological approaches in the context of one research project” (ibid, p. 6). Accordingly, the current research agenda holds that “the combination of methods is the right way to go” (ibid, p. 6) and identifies a niche in the discipline by recommending the implementation of “multi-methodological designs and advanced statistical modelling” (ibid, p. 18). Multi-methodological research is also particularly sought-after in Legal Translation Studies (LTS), as an interdiscipline seeking to tap into “methodological diversification” (Biel, 2022, p. 60).

In alignment with the multi-methodological agenda of empirical translation studies, the present study seeks to combine methods from corpus linguistics and statistical modelling. Firstly, the present study will adopt the approach of corpus linguistics, which provides insights about the nature of language discourse (Baker, 2006) and translation norms (Hu, 2016) through analysing representative samples of specialised Islamic legal and financial discourse. The study draws on the Islamic Law Corpus (ILC)2, a 9-million-word monolingual comparable corpus, i.e., one comprising translated and non-translated English-language texts on Islamic law. Adopted in whole or in part in at least forty-seven countries worldwide, Islamic law is understood as a distinct legal system implemented as a primary or secondary source of jurisprudence (Hellman, 2016, pp. 5-6). The ILC corpus is analysed using Sketch Engine text analysis software (Kilgarriff et al., 2014). Translated materials conform to Jakobson’s (2000, p. 114) model of ‘interlingual translation’, which is the traditional conception of translation as a target text that has a corresponding source text as its point of departure. Non-translated materials, on the other hand, are texts on Islamic law originally written in English but are considered translations of another culture (an Arabic Islamic culture); such texts offer mediation of an Arabic-origin culture, therefore embodying the paradigm of ‘cultural translation’, which refers to the transfer of concepts or ideas from one language or culture into another. In the present study, cultural translation relies on the use of translation as a metaphor (Pym, 2014), or on the idea of “translation without translation” (Wolf, 2007, p. 27). Exhibiting translation as a radical force of resistance, the key objective of cultural translation is to create a hybrid space for the heritage of less dominant cultures to be expressed and represented in the dominant languages (Pym, 2014). The cultural translation paradigm provides an explanation as to why translation techniques are taken into account when considering non-translated texts written in English.

Secondly, statistical regression analysis will be employed to ensure the multifactorial dimension of the research, by examining discourse as a communicative context in which lexical variation and linguistic choices are, as De Sutter and Lefer (2020, p. 6) argue, shaped by “a multitude of factors”. The factors assessed in this study pertain to contextual features, which act as explanatory variables that will be measured by the means of a logistic regression analysis using the MATLAB programming language (The MathWorks, Inc., 2022). Logistic regression can be broadly defined as “a powerful statistical technique” that estimates the effect of different explanatory (also called predictor) variables on an outcome variable (typically binary) (Brezina, 2018, pp. 105, 117, 137). The ‘outcome’ and ‘explanatory’/‘predictor’ variables correspond to ‘dependent’ and ‘independent’ variables in Saldanha and O’Brien’s terms (2014). The dependent variable is the focus element that the research seeks to measure and it is expected to vary when “exposed to varying treatment”, while the independent variable refers to the factors that could be manipulated to see whether there would be an impact on the dependent variable (ibid, p. 25). Accordingly, logistic regression is useful to study the relationship between a dichotomous dependent variable and one or more independent variables.

Within the scope of this study, the lexical variation for a given concept acts as a binary dependent variable, assuming two values (loanword versus endogenous lexeme), while ‘genre’, ‘legal function’ and ‘subject field’ are independent variables. Here, ‘lexical variation’ means the choice of one lexical unit (or of a combination of more lexical units) rather than another to refer to a culture-specific concept in a language other than the language in which the ‘original’ terms were coined. Although the datasets focus on Arabic terminology, the expression of such Arabic and Islamic concepts in English is not bound to one-to-one correspondence but may rely on paraphrases and even lengthy explanations, resulting in variation not only on terminological level but also lexical level, thus reflecting various ‘translation techniques’. Bhatia (2013) defines genre as a set of communicative events characterised by a shared purpose. However, this study treats genre and textual function as separate factors potentially influencing the preference for a lexical item over another because genres in the legal domain are associated with rhetoric and textual conventions (Prieto Ramos, 2014) but there is still a need to situate genres within the broader function of the legal text described by Šarčević (1989) as the legal effect (See Section 4).

More specifically, the analysis will harness the power of corpus processing and statistics to enable the study of 20 iconic lexical profiles (individual concepts/conceptual systems and their corresponding Arabic and English terms) that are specific to Islamic law. The 20 lexical profiles are selected based on two criteria: keyness in the corpus and formal onomasiological variation. A keyword analysis provides a feasible tool to initiate a corpus investigation. This tool helps to round out the picture about a given subject field, since “[t]he top key words reflect the domain of the focus corpus very well” (Lexical Computing Ltd, 2015, p. 3). In other words, the analysis will focus on Islamic law concepts that have the highest frequency and can be identified through either an Arabic loanword or an endogenous English lexeme. Thus, the analysis of key Islamic law concepts draws upon the model of profile-based correspondence, which is used in corpus linguistics for studying lexical variations or preferences. Speelman et al. (2003) view a profile as an instance of formal onomasiological variation, whereby a particular concept can be expressed through different linguistic means; for example, the words ‘car’ and ‘automobile’ are different labels for the same concept (ibid, p. 318). Thus, a profile (short for ‘formal onomasiological profile’) refers to a set of formal alternatives, synonymous variants, linguistic designations, or labels that can be used to designate the same concept or linguistic function, aligned with their frequencies (ibid, pp. 318-319). The existence of term variants or profiles can also be explained with reference to Freixa’s (2006) causes of ‘denominative variation’ in terminology, which could relate to differences in communicative registers (functional causes), stylistic patterns (discursive causes), or the dynamics of language contact (interlinguistic causes), among others. As an example, a profile of the financial concept [ribā] includes the loanword ribā and all synonymous naming equivalents (‘loan sharking’, ‘usurious interest’, ‘usury’, ‘interest’) identified in the corpus using the methods described in Section 3. Such naming alternatives represent semantically related endogenous lexemes. Hence, lexemes are apt for identifying semantic similarity, i.e., term variants with similar meanings. Described as a multi-feature analysis, the profile method allows for rigorous investigation as it considers the probability of lexical variation in expressing the symbols of cultural hybridity and quantifies ‘multiple features’ (i.e., synonymous equivalents) for a conceptual category rather than looking at linguistic features in isolation (Delaere & De Sutter, 2017, p. 84). The profile method also aligns with the ‘onomasiological, concept-based approach to borrowing’, which refers to the case “where not only the loanword itself but also possible receptor language equivalents are taken into consideration” (Zenner & Kristiansen, 2014, p. 1). Taken together, such empirical methods allow for a rigorous investigation in order to steer clear from speculation and bias.

The current study has an interdisciplinary scope as it crosses the boundaries of linguistics and legal studies and explores the interrelation between translation and cultural production through highlighting Islamic legal discourse in English as a prototype of the idea of cultural translation. However, the main focus of the research is linguistic analysis that aims to identify translation techniques. The linguistic analysis engages with terminology work as the project uses the Terminologue terminology management system (Měchura & Ó Raghallaigh, 2021) to organise and present terminological data. The Islamic concepts presented in Section 5 have terminological entries recorded in the Islamic Law/Finance Termbase, which is an open-access termbase specifically created as part of the current research and can be accessed via the following link: https://www.terminologue.org/IslamicLaw/.

The questions driving this research are varied in nature. The primary question of this research is descriptive, which generally seeks to identify a phenomenon based on the extracted data:

RQ1: What are the most frequent techniques used to convey culture-specific or system-bound concepts from Islamic law into English?

The secondary questions are explorative, seeking to investigate three predictor variables: function, genre, and subject field:

RQ2: Is lexical variation influenced by the function of the legal texts in question (performative versus non-performative)?

RQ3: Are there inter-genre differences within each of these categories (e.g., books vs academic articles in the non-performative category; policy- and law-making instruments vs other instruments in the performative category)?

RQ4: Are there inter-subject field differences within each of these categories (finance vs family law)?

It is worth mentioning that RQ2, RQ3, and RQ4 can be conceived as hypotheses about the effect of function and genre, and subject field as independent variables.

2. The scholarly debate on culture- or system-bound lexis in the legal sphere

Scholars have long debated the different approaches to translating terminology that is culture- or system-bound within the legal domain. Early scholarship tended to shy away from borrowing because it was viewed negatively since it “admits defeat” in Weston’s view (1991, p. 26) and signifies “laziness or cowardice” in Alcaraz Varó and Hughes’ words (2002, p. 155). Nevertheless, the debate about the translation of culture-bound legal terminology has grown in importance with reference to international institutional settings, given that they set benchmarks for specialised knowledge based on multilingual corpora and terminological resources. Kuriačková (2018) reveals how EU legislative documents consistently retain the source language term along with its paraphrase when handling culture-bound concepts. Kuriačková’s finding is based on analysing 11 terms across five languages (English, French, German, Slovak, and Czech), which were chose due to their relevance to EU legislative documents as they primarily denote geographical names, political offices, and administrative divisions. Of relevance here is also the terminological harmonisation of Canadian law, which advocates combining the different terms used to denote a given concept under both common law and civil law (Doczekalsa & Biel, 2022, pp. 107-108).

The precise effect of situational factors on translation choices has been questioned by further studies. Biel (2022, p. 70) points out that the “dominant trend is a receiver-oriented approach” in intersystemic translation between legal systems while indicating that foreignising techniques are more typical in intrasystemic translation, which occurs within a single legal system, particularly for supranational terms (ibid, pp. 67-70). Like Biel, Prieto Ramos (2014) places emphasis on the role of the context; however, he adopts a source-oriented approach to deal with system incongruity as opposed to ‘the receiver-oriented approach’. Prieto Ramos (2014, p. 122) argues that the overall translation strategy for culture-specific concepts takes into account macro parameters including the directionality of legal systems as well as textual categories such as legal text-types and genres. By way of illustration, translation decision-making can vary depending on whether the translational action takes place within a single national system or between different legal systems. In the case of system incongruity, Prieto Ramos recognises the need to avoid using functional equivalents in the target system, noting that the cultural markers that distinguish the source culture must be retained (ibid, p. 123). Here, fulfilling adequacy is a matter of ensuring the foreign eye is able to capture the existence of cultural specificities through reliance on techniques that signal conceptual hybridity, such as borrowing, literal translation and/or descriptive formulae (ibid, p. 124). To avoid the confusion that results from the use of approximate renderings, “functional equivalents valid in one national system alone are normally ruled out” (ibid, p. 128). Finally, Prieto Ramos maintains that borrowing is a viable option when emphasis is needed on the cultural specificity of the source-system term (ibid, p. 128). Therefore, decision-making has been widely held to be dependent on variable contextual and situational factors.

The current study constitutes an attempt to depart from the mainstream focus on European culture in research on legal translation and terminology amidst the “preeminence of major European languages in LTS” whereas lesser-dominant languages are still under-represented or under-researched (Prieto Ramos, 2019, pp. 2-3). While previous studies that used legal corpora to investigate culture-specific items focused on system-bound terms (e.g., Vigier & Sánchez, 2017; Peruzzo, 2019), the present research explores a category of terminology that is not only associated with a different system, but also bears religious significance. Some studies have also indicated a correlation between power relations and lexical choices in translational discourse, e.g., the effect of the hegemony of the Soviet Union on Finnish translated discourse (Santalahti & Mikhailov, 2019) and the influence of the EU on Polish translated discourse (Biel, 2014). If this hypothesis holds true for the translation direction from a major to a minor culture (i.e., translating across power differentials), as discussed in previous studies, then this raises intriguing questions for the effect of using loanwords when translating in the opposite direction, i.e., from a minor to a major culture. Several questions also remain about the role of translation in expressing the concepts of Islamic law, how its translated terms are shaped in different ways and what the translation norms are. To answer these questions, the present study will mainly adopt a corpus linguistics approach, which provides insights into the nature of language, discourse, and translation norms through analysing representative samples of this particular discourse.

3. Multi-methodological design: corpus linguistics and statistical modelling

The research adopts a multi-methodological design. The study first quantifies the different linguistic techniques used to render shariʿa-based concepts in English, with reference to Šarčević’s (1985) typology, which is closely tailored to culture-bound concepts in the legal domain, i.e., concepts that convey a social reality specific to the country, system, or culture of the source language. Building on Šarčević’s (1985) typology, the research proposes the following set of techniques: descriptive substitute, adaptation, neologism, loanword, supplementation, and lexical expansion. A descriptive substitute is intended to express the form or function of the culture-bound concept. Adaptation is the technique of using a similar equivalent from the conventional financial/legal system, as opposed to the Islamic counterpart. Neologism relies on coining new linguistic labels to express the Islamic legal concept. It is worth noting here that endogenous lexemes result from the use of the aforementioned three techniques (descriptive substitute, adaptation, neologism). On the other hand, loanword refers to the practice of borrowing an Arabic word in English script. Supplementation is an auxiliary technique used to complement the loanword with the addition of a hypernym, superordinate, or a more general term. Lexical expansion is another auxiliary technique used to add complementary information in the form of a paraphrase, explanation, or definition. The corpus annotation was carried out with reference to Šarčević’s (1985) typology of translation techniques in order to explore ‘translation’ norms based on linguistic frequency in the corpus.

Using Sketch Engine software, the analysis starts with a bottom-up query to build a profile set through a ‘profile-based correspondence analysis’ (Delaere & De Sutter, 2017), which considers the probability of lexical variation in expressing a conceptual category. Firstly, through the ‘keywords’ function, Arabic loanwords that feature in the English-language discourse on Islamic law are extracted. Secondly, ‘collocations’ and ‘concordance’ analysis are employed to identify loanwords that have an ‘endogenous’ counterpart lexeme, meaning a close English equivalent or a synonymous naming alternative (Delaere & De Sutter, 2017). Reading concordance results also helped to identify low-frequency variants (e.g., standalone neologisms) although they might be merely idiosyncratic choices rather than high-frequency variants which attest to patterns of translational behaviour.

To establish the data sets, the study focuses on 20 lexical profiles (20 Islamic concepts or conceptual systems: 10 from finance and 10 from family law); each profile will consist of the Arabic loanword and all corresponding endogenous variants for the same conceptual category. A concordance analysis of the selected profiles is carried out to investigate the different translation techniques. The concordance analysis involves annotating a random sample of concordance lines covering the 20 concepts. For each concept, 200 instances of the loanword versus 200 instances of the identified endogenous lexemes are annotated. Thus, the sample total is 8,000 concordance lines — however, 602 instances were found to be not applicable. In the interests of exhaustiveness, corpus queries were run on all the different orthographic forms of transliterated Arabic loanwords as well as all endogenous English alternatives that were identified in the analysis process, which rules out the possibility of a biased selection of linguistic labels. Furthermore, separate concordance queries are performed on each profile in order to obtain clusters containing no loanword. The initial query is run on the loanword and its different orthographic forms, while the subsequent query/ies are run on all endogenous lexemes identified for a given profile.

Finally, logistic regression is implemented to measure the influence of the explanatory variables, ‘genre’, ‘legal function’ (i.e., performative versus non-performative function), and ‘subject field’ on the choice between an Arabic loanword and an endogenous English lexeme. This statistical logistic regression employs a quantitative analysis using MATLAB programming software. This regression model involves searching for the variants of each ‘profile’ in each of the different genres in the corpus and using the corpus query results as raw data to run a logistic regression analysis to estimate the probability of each lexical variant occurring in a particular genre, legal function, or subject field as a percentage. The efficacy of the logistic regression analysis is due to its ability to determine the simultaneous impact of different predictor variables on an outcome variable.

4. Corpus information

This study is based on the Islamic Law Corpus (ICL), a specialised monolingual corpus comprising over 9 million words and is divided thematically into two subcorpora: Islamic finance and family law. This thematic classification reflects the position of Islamic law in the contemporary settings, i.e., the branches where Islamic law still holds significance in the present world are family law and commercial law, the latter being represented by the shariʿa-compliant system of Islamic finance. Kettell (2010, p. vii) defines Islamic finance as a financial system regulated by Islamic law since shariʿa constitutes “the basis for the creation of Islamic financial products”. Thus, Islamic finance is considered a living example of the application of shariʿa rules in the commercial and financial domain.

The corpus comprises 839 documents: 709 originally written in English; 90 bilingual documents (including 86 English-Arabic, 3 English-Malay, 1 English-Urdu). The total number of translated documents is 40 (including 39 Arabic-English, 1 Maldivian Language Dhivehi-English). The difference between bilingual and translated documents is that the former refers to documents issued in two languages by the same entity and often have a double-page layout, whereas the latter documents have an explicit translated status.

The corpus is considered multi-genre since each subcorpus is composed of five genres. Each genre either has a performative or a non-performative function based on whether it is intended for legal application or for information purposes only. Firstly, the performative category comprises applied genres that have a binding force, including ‘law and policy-making instruments’ and ‘other instruments’. Whereas law-making instruments are of a purely legislative nature (e.g., laws, codes, acts, bills, and ordinances), policy-making instruments are prescriptive documents issued by regulatory and standardisation bodies (e.g., published standards, instructions, resolutions, and prudential rules). Other instruments cover a range of underrepresented text types, from private legal documents and administrative documents (such as contracts, agreements, application forms) to judicial texts (such as court and litigation documents). Secondly, the non-performative category covers purely informative genres (e.g., books, academic articles, grey literature). While books and academic articles are both scholarly materials, the genre of grey literature brought together a variety of industry materials (e.g., working papers, discussion papers, handbooks, bulletins, booklets, guides, reports, technical releases and technical notes) and less specialised media texts intended for the general public (e.g., online newspaper articles, web articles, and web content, i.e., product and services information on the websites of stakeholders). This design identifies whether culture-specific concepts are expressed differently across diverse contexts or genres. Tables 4.1. to 4.5. show the corpus statistics.

4.1 Corpus size

| Islamic Law Corpus (ILC) | |

|---|---|

| Tokens | 11,265,746 |

| Words | 9,380,874 |

| Sentences | 327,160 |

| Total documents | 839 |

Table 4.1. Corpus information

| Subcorpus | Tokens | No. of Documents | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Islamic Finance | 7,421,330 | 463 | 65.875 |

| Family Law | 3,844,416 | 376 | 34.125 |

Table 4.2. Subcorpus sizes

| Genre | Tokens | No. of Documents | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Books FN | 3,855,486 | 30 | 34.223 |

| Articles FN | 645,022 | 80 | 5.726 |

| Grey Literature FN | 933,289 | 100 | 8.284 |

| Policy-making Instruments FN | 1,057,532 | 41 | 9.387 |

| Other Instruments FN | 930,001 | 212 | 8.255 |

Table 4.3. Genre sizes - Islamic finance (FN)

| Genre | Tokens | No. of Documents | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Books FL | 1,196,158 | 10 | 10.618 |

| Articles FL | 1,084,151 | 80 | 9.623 |

| Grey Literature FL | 616,600 | 106 | 5.473 |

| Law-making Instruments FL | 744,819 | 124 | 6.611 |

| Other Instruments FL | 202,688 | 56 | 1.799 |

Table 4.4. Genre sizes - Islamic family law (FL)

| Document status | Finance | Family law | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Original in English | 378 | 331 | 709 |

| Bilingual | 85 | 5 | 90 |

| Translated | 0 | 40 | 40 |

Table 4.5. Document status

5. Lexical profiles

This section presents the ten most frequent lexical profiles in each subcorpus, referring to/designating finance and family concepts, and provides their loanword orthographic forms and various endogenous lexemes (see Tables 5.1. and 5.2.). The lexical profiles are selected based on their keyness as determined by keyword frequency and rank. The endogenous lexemes are sorted based on two criteria: (1) degree of relevance to the Islamic concept, i.e., certain labels make a closer correspondence than others; (2) absolute frequency. For example, the labels ‘silent partnership’ and ‘passive partnership’ can be more associated with the concept of [murābaḥa] than ‘profit-sharing’ can, as the latter is a polysemous term that has a broader semantic range.

5.1 Finance

| Lexical profiles | Loanwords | Frequency | Endogenous lexemes | Frequency | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [ṣukūk]3 | sukuk sukūk ṣukūk |

13,223 | Islamic bonds | 293 | |

| [takāful] | takaful takāful |

9,607 | Islamic insurance | 549 | |

| [murābaḥa] | murabaha murabahah murābahah murābaḥa al-murabaha murābaḥah |

5,918 | cost-plus | 173 | |

| cost plus profit | 54 | ||||

| cost-plus financing | 48 | ||||

| cost-plus sale | 36 | ||||

| cost-plus contract | 2 | ||||

| mark-up | 397 | ||||

| mark-up sale | 12 | ||||

| mark-up financing | 6 | ||||

| mark-up contract | 6 | ||||

| mark-up transactions | 5 | ||||

| [ijāra] | ijarah ijara ijārah ijāra al-ijara al-ijarah |

5,366 | Islamic leasing/Islamic lease | 57 | |

| leasing | 941 | ||||

| lease | 5,477 | ||||

| [muḍāraba] | mudarabah mudaraba muḍārabah mudharabah muḍāraba mudārabah mudharaba al-mudarabah modaraba |

6,960 | silent partnership | 69 | |

| trust financing | 44 | ||||

| financial partnership | 13 | ||||

| trustee finance | 9 | ||||

| passive partnership | 3 | ||||

| trustee profit-sharing | 3 | ||||

| trust partnership | 1 | ||||

| trust investment partnership | 1 | ||||

| profit-sharing | 697 | ||||

| profit sharing | 393 | ||||

| [mushāraka] | musharakah musharaka musyarakah mushārakah |

5,009 | equity participation | 140 | |

| equity partnership | 51 | ||||

| joint partnership | 2 | ||||

| joint venture | 436 | ||||

| [istiṣnāʿ] | Istisna istisnā |

2,323 | manufacturing contract | 20 | |

| commissioned manufacture | 10 | ||||

| manufacturing sale contract | 3 | ||||

| progressive financing | 3 | ||||

| sale by order | 3 | ||||

| purchase by order | 1 | ||||

| manufacture | 492 | ||||

| manufacturing | 320 | ||||

| [ribā] | riba ribā ribit |

3,740 | loan sharking | 2 | |

| usurious interest | 4 | ||||

| usury | 651 | ||||

| interest | 9,554 | ||||

| [qarḍ ḥasan] | qard qarḍ qardh qard-al-hassan qard-al-hasan qardhul |

2,666 | interest-free loan/ interest free loan | 281 | |

| benevolent loan | 89 | ||||

| beautiful loan | 19 | ||||

| good loan | 12 | ||||

| charitable loan | 6 | ||||

| virtuous loan | 4 | ||||

| voluntary loan | 4 | ||||

| bona fide loan | 3 | ||||

| [salam] | salam al-salam |

3,139 | forward contract | 141 | |

| forward sale | 134 | ||||

| advance purchase | 16 | ||||

| forward transaction | 15 | ||||

| purchase with deferred delivery | 14 | ||||

| prepaid forward sale | 6 | ||||

| advance purchase contract | 5 | ||||

| deferred delivery purchase | 3 | ||||

| pre-paid purchase | 2 | ||||

| forward financing | 1 | ||||

| forward-purchasing | 1 | ||||

| pre-paid sale | 1 | ||||

| advanced sale | 1 | ||||

| pre-payment transaction | 1 |

Table 5.1. Lexical profiles for the top ten Islamic financial concepts

5.2 Family law

| Lexical profiles | Loanwords | Frequency | Endogenous lexemes | Frequency | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [mahr/ṣadāq] | mahr mehr mehar ṣadāq sadaq |

3,850 | dower | 2,190 | |

| dowry | 1,071 | ||||

| marriage gift | 80 | ||||

| bridal gift | 45 | ||||

| bride price | 20 | ||||

| bride-price | 22 | ||||

| marital gift | 9 | ||||

| brideswealth | 6 | ||||

| marriage-gift | 6 | ||||

| morning gift | 3 | ||||

| [ʿidda] | iddat iddah idda ʿidda edat |

1,242 | waiting period | 740 | |

| period of waiting | 8 | ||||

| period of abstinence | 5 | ||||

| mourning period | 2 | ||||

| Divorce initiated by the husband [ṭalāq/ ẓihār/ īlāʾ / liʿān / rajʿī] | talaq ṭalāq talāq talaaq talak |

3,534 | Islamic divorce | 420 | |

| repudiation | 573 | ||||

| unilateral divorce | 95 | ||||

| divorce by the husband | 31 | ||||

| male-initiated divorce | 3 | ||||

zihar ẓihār zihār |

108 | injurious assimilation | 5 | ||

| permanent desertion | 5 | ||||

| improper comparison | 1 | ||||

ila īlāʾ īla |

86 | vow of continence | 6 | ||

li'an lian liʿan liʿān |

57 | mutual imprecation | 15 | ||

| denial of fatherhood | 1 | ||||

rajyee rajʿī rajī raj'i rajie |

47 | revocable divorce | 109 | ||

| Divorce initiated by the wife or via court: [khulʿ/ faskh / tafrīq / mukhālaʿa / mubāraʾa / shiqāq / taṭlīq] | khula khul khulʿ |

2,151 | judicial divorce | 466 | |

| redemptive divorce | 7 | ||||

| redemption | 45 | ||||

| rescission by agreement | 1 | ||||

| wife initiated divorce | 4 | ||||

| wife-initiated divorce | 6 | ||||

| divorce by redemption | 13 | ||||

faskh fasakh |

336 | judicial rescission | 2 | ||

| judicial divorce | 466 | ||||

| judicial dissolution | 34 | ||||

| annulment | 477 | ||||

| marriage dissolution | 42 | ||||

| abrogation | 28 | ||||

| divorce through court | 2 | ||||

| fault divorce | 6 | ||||

| fault marriage | 1 | ||||

tafriq tafrīq tafreeq |

122 | judicially ordered divorce | 2 | ||

| judicial divorce | 466 | ||||

| annulment | 477 | ||||

mukhala mukhāla |

115 | mutually agreed divorce | 4 | ||

| mutually negotiated divorce | 3 | ||||

| divorce for compensation | 2 | ||||

mubaraat mubarat mubaraa mubāraa mubāraʾa mubaret mubara mubarah mubar'at |

102 | mutual freeing | 2 | ||

| mutual divorce | 2 | ||||

shiqaq shiqāq |

88 | discord | 158 | ||

| strife | 33 | ||||

| breach | 205 | ||||

| irretrievable breakdown | 22 | ||||

tatleeq tatliq tatliq tatlīq |

44 | divorcement | 32 | ||

| forced divorce | 3 | ||||

| [nikāh] | nikah nikāh nikahnama |

1,438 | Islamic marriage | 656 | |

| Muslim marriage | 1,046 | ||||

| Islamic ceremony | 35 | ||||

| Islamic marriage ceremony | 30 | ||||

| Islamic marital contract | 7 | ||||

| [zinā] | zina zinä zinā |

830 | adultery | 391 | |

| fornication | 83 | ||||

| illicit sex | 11 | ||||

| unlawful sexual intercourse | 10 | ||||

| unlawful intercourse | 9 | ||||

| unlawful sex | 8 | ||||

| illicit sexual intercourse | 6 | ||||

| sex outside marriage | 3 | ||||

| extramarital sex | 2 | ||||

| [nafaqa] | nafaqa | 429 | alimony | 654 | |

| financial support | 94 | ||||

| spousal maintenance | 68 | ||||

| financial compensation | 46 | ||||

| marital support | 16 | ||||

| maintenance | 3,186 | ||||

| [walī] | wali walī |

519 | marriage guardian | 80 | |

| male guardian | 50 | ||||

| marital guardian | 7 | ||||

| guardian of bride | 5 | ||||

| bride's representative | 3 | ||||

| woman's proxy | 1 | ||||

| matrimonial tutor | 1 | ||||

| guardian | 2,351 | ||||

| [mutʿa] | mutah muta mut mutʿa mutaa mut’a |

573 | a) temporary marriage | 164 | |

| b) post-divorce compensation: | |||||

| post-divorce | 87 | ||||

| post-divorce maintenance | 27 | ||||

| consolatory gift | 25 | ||||

| gift of consolation | 8 | ||||

| post-divorce gift | 7 | ||||

| divorce compensation | 4 | ||||

| consolation payment | 4 | ||||

| divorce gift | 3 | ||||

| financial consolation | 1 | ||||

| [nushūz] | nushuz nushūz nusyuz nashiz nashiza nashiza nāshiz |

265 | disobedient | 146 | |

| disobedience | 124 | ||||

| recalcitrant | 47 | ||||

| disobedient wife | 23 | ||||

| recalcitrance | 21 | ||||

| rebellious | 18 | ||||

| rebellion | 16 | ||||

| act of disobedience | 5 | ||||

| rebelliousness | 5 | ||||

| refactory wife | 2 | ||||

| rebellious act | 1 | ||||

| insubordinate wife | 1 | ||||

| nonconformist | 1 |

Table 5.2. Lexical profiles for the top ten Islamic family law concepts

The next section draws the various strands of the study together by discussing the findings which emerged from the corpus and regression analyses.

6. Corpus findings — overview of translation techniques and their frequency

This section contributes to answer RQ1 as it identifies the techniques used in translating culture-specific concepts related to Islamic finance and family law into English. It also provides a categorisation of the translation techniques by breaking them down into two main categories: standalone techniques and cluster techniques (couplets, triplets, and quadruplets).

6.1 Standalone techniques

The principal finding of this research is that, based on an analysis of 8,000 concordance lines featuring 20 lexical profiles, loanwords constitute the most frequently used technique in the cultural translation of Islamic law concepts into English. The standalone loanword technique represented 35.8% or 1,432 instances out of 4,000 concordance lines investigating Islamic financial concepts as well as 34.3% or 1,372 instances out of 4,000 concordance lines investigating Islamic family law concepts. Accordingly, the specialised discourse of Islamic law is a hybrid discourse since it is characterised by loanwords from Arabic and Islamic culture. Islamic legal discourse in English relies on hybrid diction through interference of Arabic words in the pursuit towards retaining symbols of linguistic hybridity and amalgamating the minor and major languages in hybrid texts, thus creating cultural diversity in language.

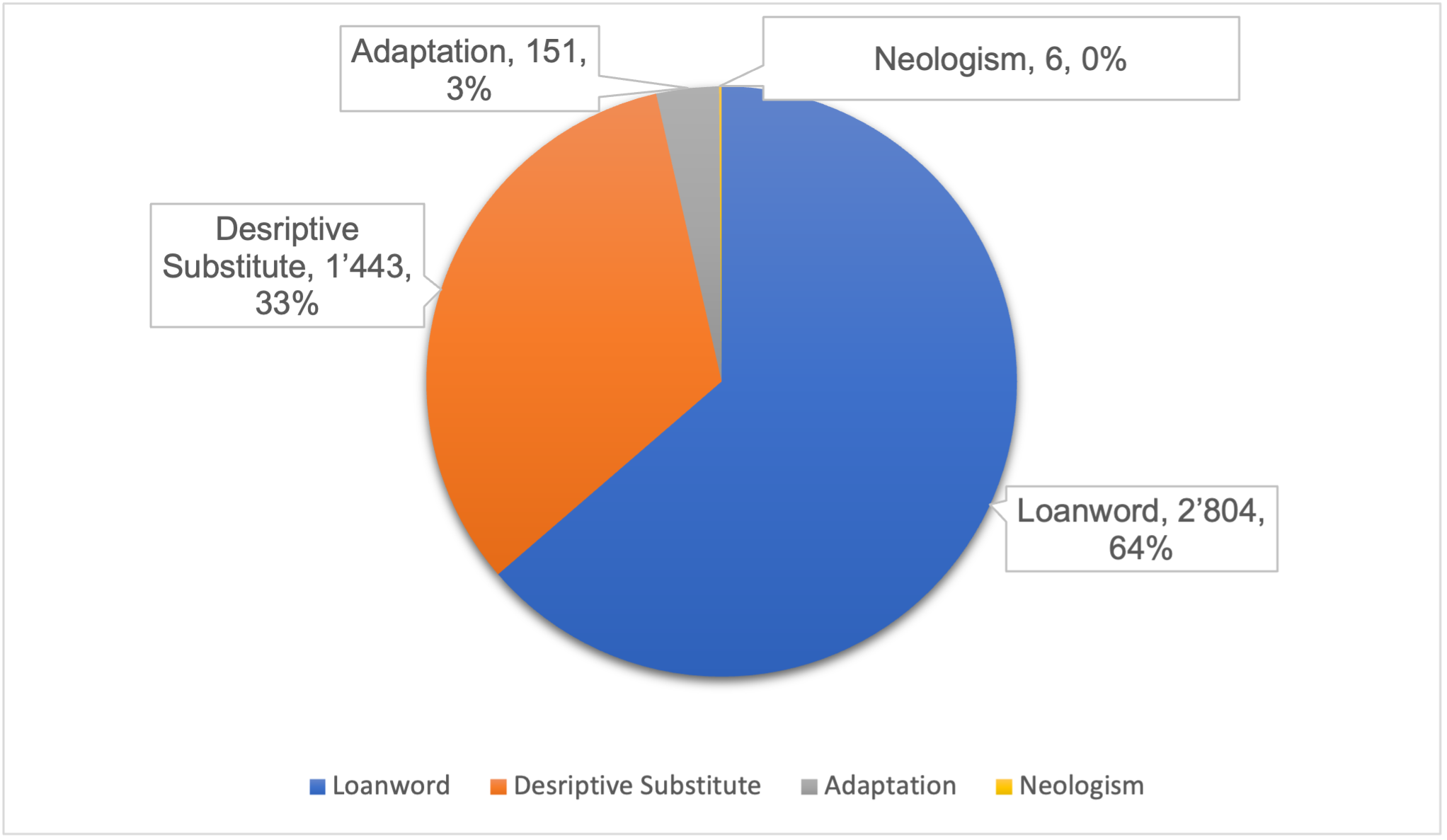

Figure 6.1. displays the standalone (individual) techniques used in translating culture-specific concepts in Islamic legal discourse. The frequency is expressed by the number and percentage of occurrences.

Figure 6.1. Standalone techniques (total: 4,404)

The current study also identified three other standalone techniques that employ endogenous lexemes (i.e., approximate English equivalents): descriptive substitute, adaptation, and neologism. Such techniques, however, differ in their orientation: descriptive substitute and adaptation create straightforward target-oriented endogenous lexemes, whereas the neologism technique occasionally results in perplexing endogenous lexemes. Certain techniques are also found to be relatively more typical of a given subject-field.

The standalone descriptive substitute is more widely used in family law than in finance, accounting for 27.92% (1,117 instances) and 8.15% (326 instances), respectively. A possible justification is that family law as a thematic category addresses concepts which, despite including culture-bound dimensions, still reflect underlying generally familiar notions (e.g., marriage or spousal maintenance, etc.) and are thus less prone to system incongruity than other concepts. Thus, what follows is that the more specific the concept is to the source culture, the more likely it is to be expressed as an Arabic loanword. Indeed, Islamic finance has a more profound culture-specific nature than Islamic family law, a finding which is supported by the results from the finance subcorpus in which the standalone loanword recorded 35.8% (1,432 instances), whereas the standalone descriptive substitute constituted 8.15% (326 instances). However, family law shows a narrower gap between loanwords (34.3%; 1,372 instances) and descriptive substitutes (27.92%; 1,117 instances).

Although adaptation is generally an effective technique in producing explicitly target-oriented endogenous lexemes, it is not a very common standalone technique: adaptation accounts for 1.92% (77 instances) in finance and 1.85% (74 instances) in family law. Finally, the technique of neologism is the least used standalone technique: 0.13% (5 instances) in family law versus 0.025% (1 instance) in finance, possibly because it generates peculiar endogenous lexemes that may immediately be discerned as a foreign transplanted concept. In general, it can be observed that family law relies on standalone techniques significantly more than finance, given that standalone techniques as a broad category recorded 2,568 instances (64.2%) and 1,836 instances (45.9%), respectively.

6.2 Cluster techniques

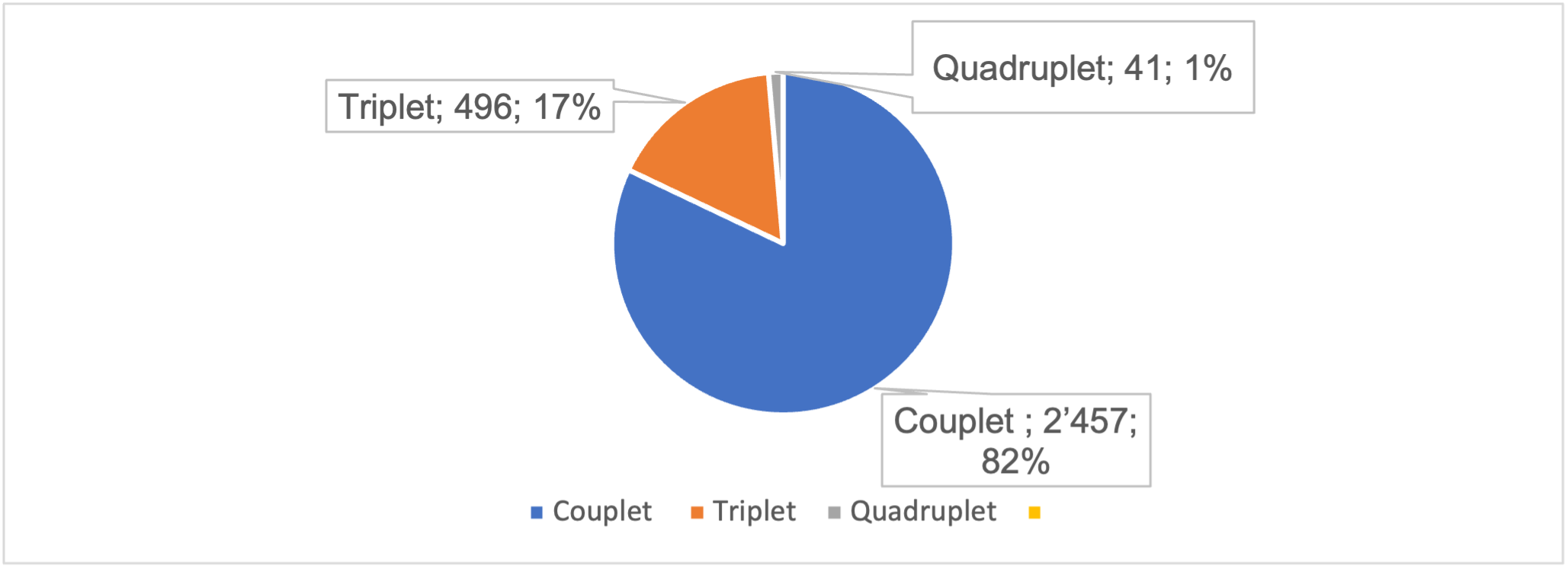

Another key finding from the corpus linguistic analysis is that the English-language discourse on Islamic law typically uses cluster techniques in expressing cultural phenomena. Such cluster techniques involve three broad categories: couplet, triplet and quadruplet.

Figure 6.2. shows the cluster techniques used in translating culture-specific concepts in Islamic legal discourse.

Figure 6.2. Cluster techniques (total: 2,994)

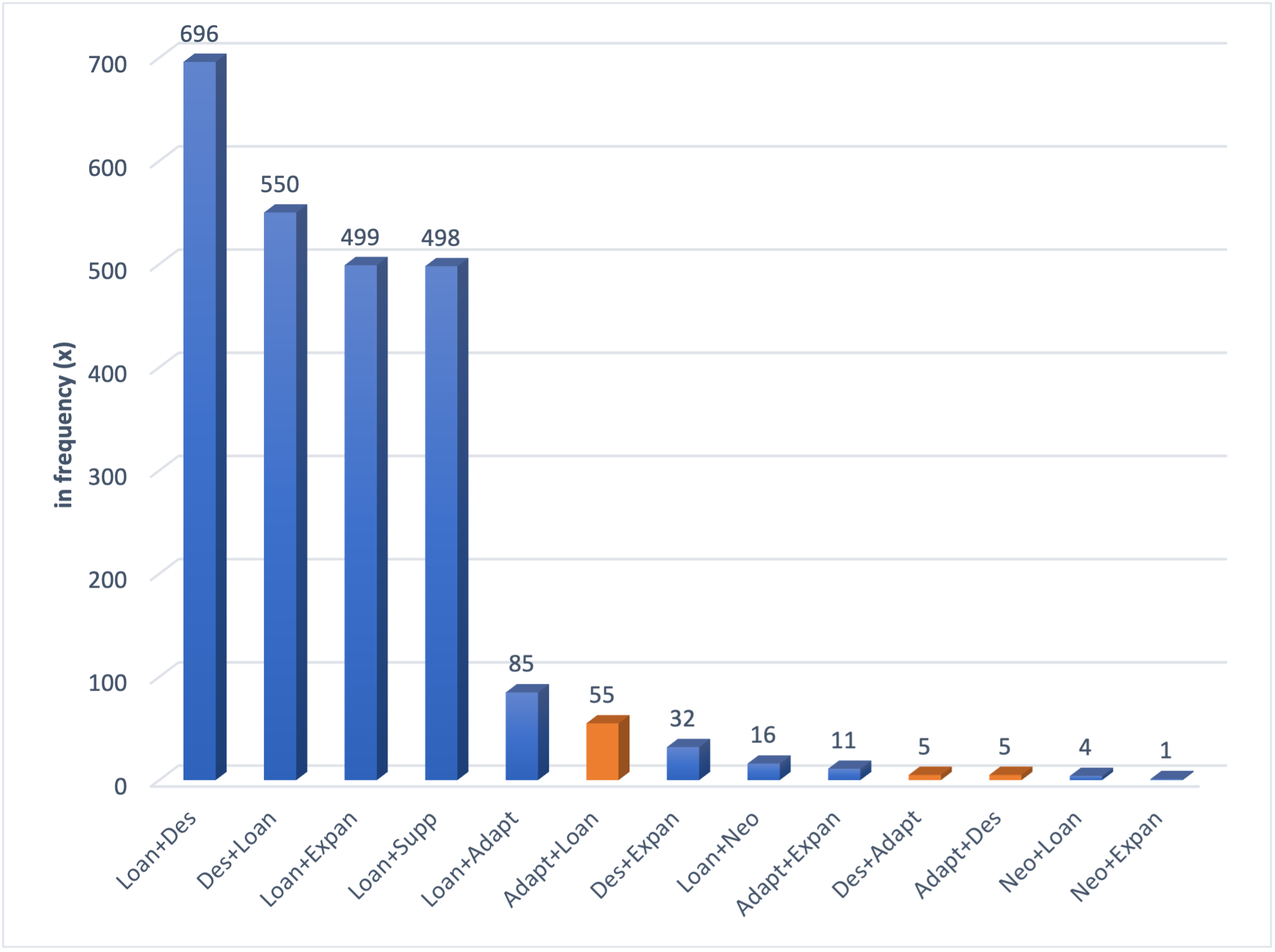

Islamic legal discourse is characterised by the use of translation couplets (mainly through combining loanword and endogenous English variants). Here, endogenous English lexemes were more frequently based on descriptive substitutes, rather than adaptations. Islamic finance also shows a stronger preference for couplets (36.6%; 1,467 instances) than family law (24.75%; 990 instances). In terms of frequency, the couplet Loan+Des is the most frequent form of couplet in the finance subcorpus, with 410 instances (10.25%), while it came in second accounting for 286 instances (7.15%) in family law. The reverse form of this couplet (Des+Loan) is the most common form of couplet in family law, recording 8.05% (322 instances), while it came fourth in finance accounting for 5.7% (228 instances). Consequently, it is evident that Islamic finance tends to place the loanword before the descriptive substitute, whereas family law tends to place the descriptive substitute first. Islamic finance as a scholarly discipline and professional industry seems to give priority to the loanword or introducing the ‘other’ to the West. Meanwhile, the synergy between the loanword and adaptation is modest, as the couplets Loan+Adapt and Adapt+Loan recorded 2.05% (82 instances) in finance and 1.45% (58 instances) in family law. Similarly, there is a minor interconnectedness between loanword and neologism, as the couplets Loan+Neo and Neo+Loan represented 0.4% (16 instances) in family law and 0.1% (4 instances) in finance. On very few occasions, adaptation and descriptive substitute conjoin; the couplets Adapt+Des and Des+Adapt constituted 0.22% (9 instances) in finance, while the couplet Des+Adapt recorded 0.025% (1 instance) in family law.

Figure 6.3. displays the forms of couplets and their frequency

Figure 6.3. Couplets (total: 2,457)

Perhaps the most fundamental auxiliary technique within the couplet category is supplementation, which combines with loanwords in the second most frequent form of couplet in finance and the fourth most frequent type of couplet in family law. Supplementation is a vital technique since it allows Arabic loanwords to establish ground and become integrated into the English language. This is because the supplementation of a loanword with a hypernym or a more general endogenous term (as in ‘murābaḥa financing’, ‘mushāraka venture’, ‘ijāra contract’, ‘khulʿ divorce’) helps in communicating the essential characteristics of the concepts in question. The supplementation of a loanword is, however, more typical of finance rather than family law, where the couplet Loan+Supp recorded 9.67% (387 instances) and 2.77% (111 instances), respectively. Thus, Islamic finance draws significantly on supplementation to better accommodate Arabic labels within the Latin script used in English.

Lexical expansion is another critical auxiliary technique within the couplet category. Generally, Islamic legal discourse relies on lexical expansions to contextualise the Islamic term through paraphrases, definitions, or explanations. For instance, although multiple endogenous lexemes are found in the corpus for the concept of [qarḍ ḥasan] (including ‘interest-free loan’, ‘interest free loan’, ‘benevolent loan’, ‘good loan’, ‘charitable loan’, and ‘virtuous loan’, ‘bona fide loan’, and ‘beautiful loan’), sometimes more elaboration was used to clarify that it is a non-interest-bearing loan provided on a goodwill basis, which requires the borrower to only pay back the original amount at the end of the agreed term or to indicate that it is provided to the needy groups. The couplet Loan+Expan occupies the third rank as the most frequent form of couplet under both finance and family law. However, the frequency of the couplet Loan+Expan is relatively higher in finance (8.32%; 333 instances) than family law (4.15%; 166 instances) — all the more evidence that Islamic finance has a more visible culture-specific dimension. However, lexical expansions are minimally used with endogenous lexemes. In the finance subcorpus, Adapt+Expan, Des+Expan, and Neo+Expan recorded 0.2% (8 instances), 0.125% (5 instances), and 0.025% (1 instance), respectively. In the family law subcorpus, Des+Expan and Adapt+Expan recorded 0.67% (27 instances) and 0.075% (3 instances), respectively.

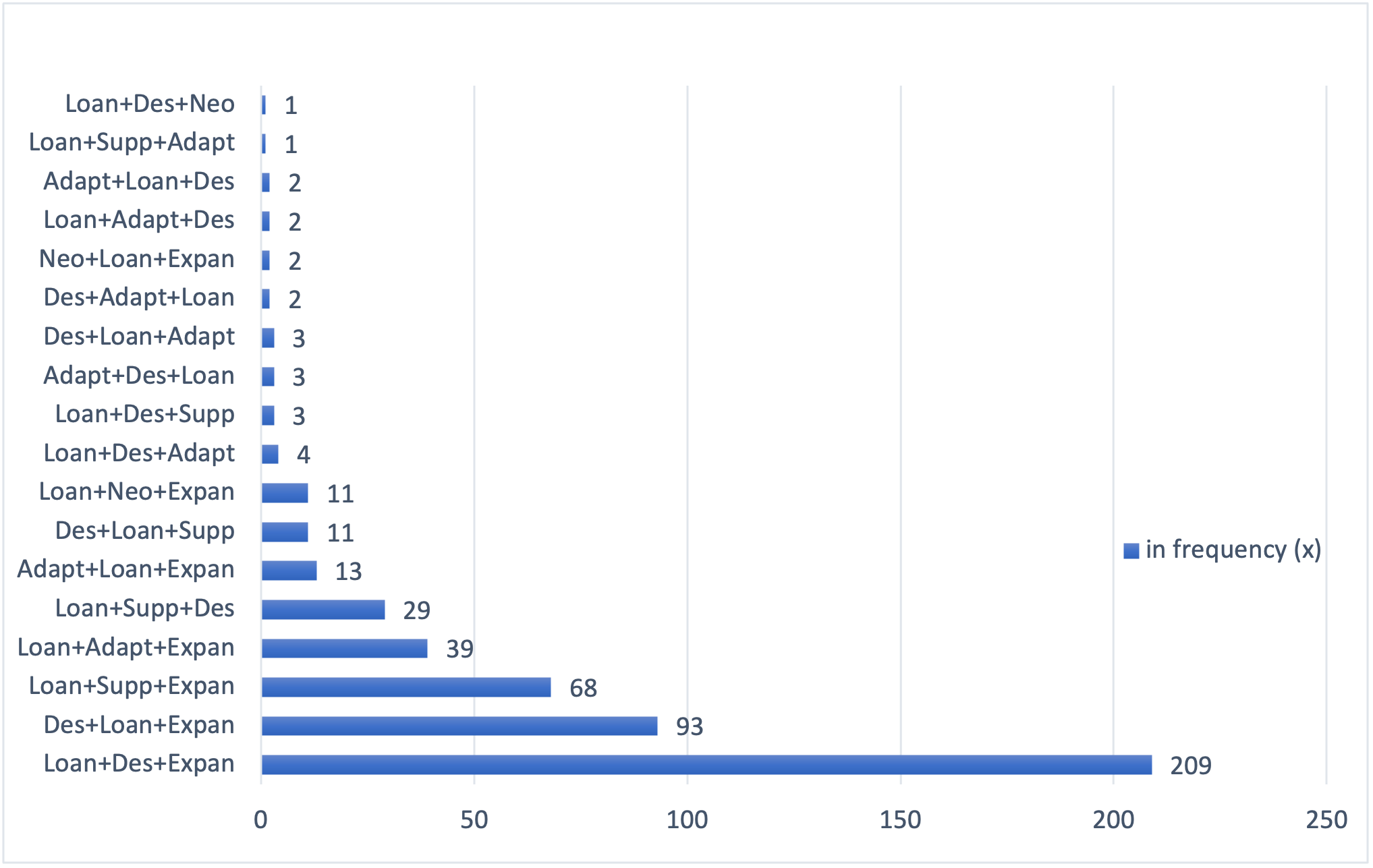

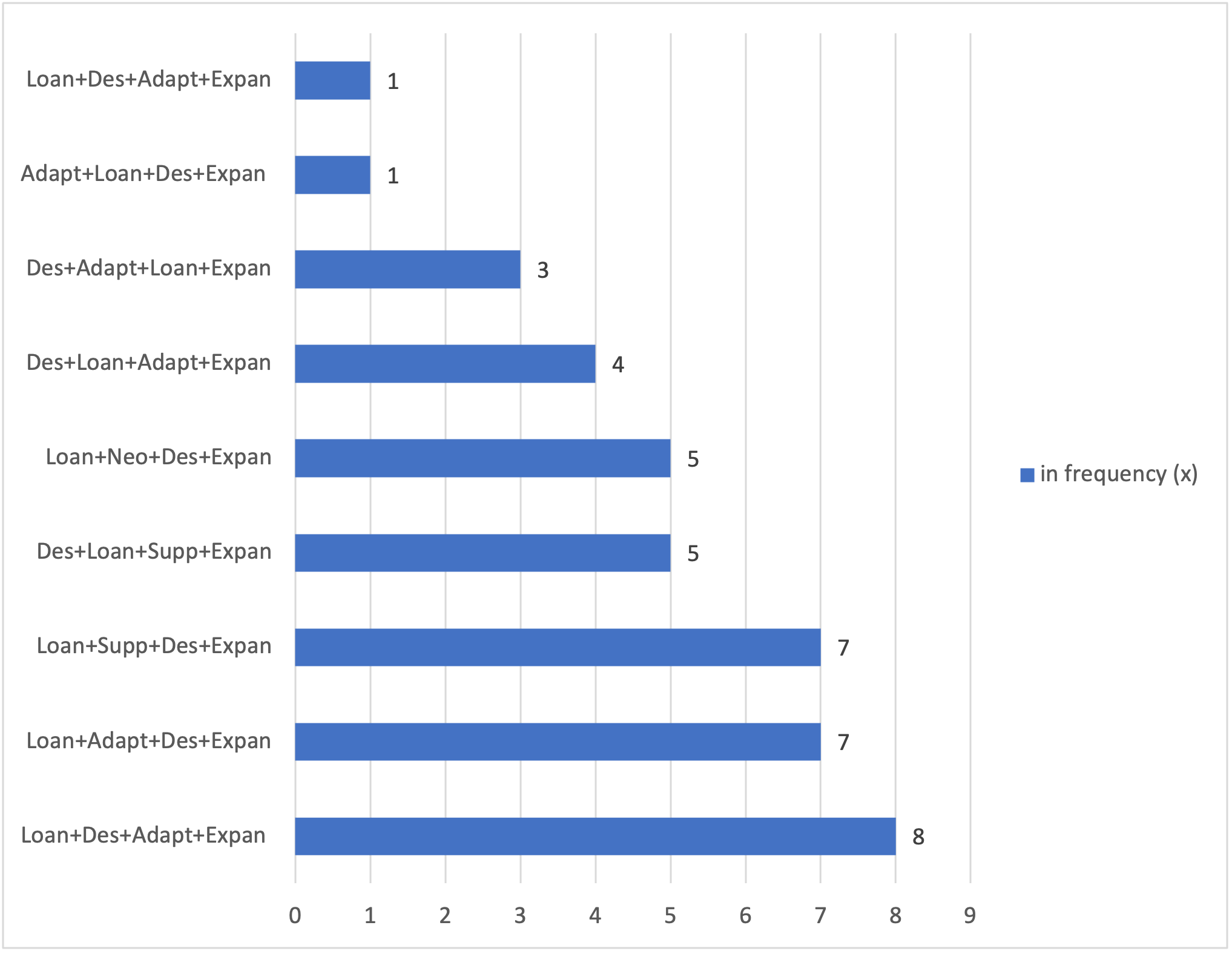

Figure 6.4. displays the forms of triplets and their frequency.

Figure 6.4. Triplets (total: 496)

Figure 6.5. displays the forms of quadruplets and their frequency.

Figure 6.5. Quadruplets (total: 41)

Another important finding is that culture-specific concepts in Islamic law often lend themselves to more intricate longer clusters of translation techniques. Triplets recorded 7.125% (285 instances) in finance and 5.275% (211 instances) in family law. The synthesis between a loanword, a descriptive substitute and a lexical expansion creates the most frequent forms of triplets (Loan+Des+Expan and Des+Loan+Expan). Such triplet forms jointly recorded 37.75% (151 instances) in finance and 37.75% (151 instance) in family law. The triplet Loan+Supp+Expan is particularly characteristic of finance 1.5% (60 instances) versus 0.2% (8 instances) in family law. The triplets Loan+Adapt+Expan and Loan+Supp+Des are also among the most noticeable; the former recorded 0.57% (23 instances) in finance versus 0.4% (16 instances) in family law, while the latter represented 0.32% (13 instances) in finance and 0.4% (16 instances) in family law. Quadruplets have also been identified on small scale, as they represented 0.67% (27 instances) in finance and 0.35% (14 instances) in family law. The most common forms of quadruplets were as follows: Loan+Des+Adapt+Expan (0.2%; 8 instances) in finance and Des+Loan+Supp+Expan (0.13%; 5 instances) in family law. For a more comprehensive review of all the forms of triplets and quadruplets, see the categorisation of translation techniques in Figures 6.4. and 6.5. Overall, Islamic finance as a subject field encompasses a larger proportion of triplets and quadruplets than family law, reinforcing its cultural specificity or an ideological agenda to explicate the background of signature terms.

Regression findings

Overall, the regression analysis came in line with the linguistic analysis by suggesting that Islamic legal discourse shows a preference for the use of Arabic loanwords versus endogenous English lexemes. In particular, the logistic regression analysis shows how independent explanatory variables may impact on the dependent variable of the research, attempting to address RQ2, RQ3 and RQ4.

7.1 Frequency of the loanwords versus endogenous lexemes across genres and textual functions

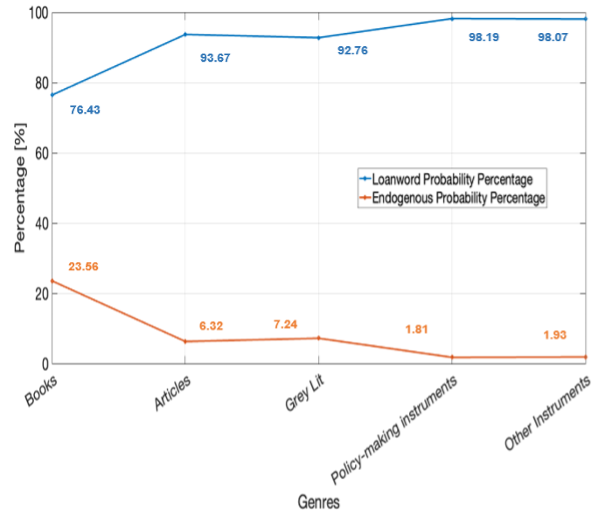

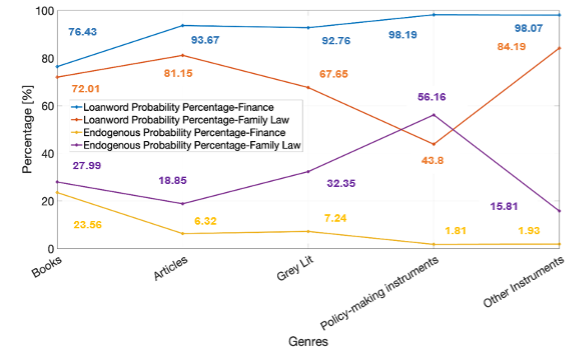

7.1.1 Probability percentages by genre - finance

Figure 7.1. shows the probability percentages of having a loanword versus an endogenous lexeme across the different genres in the finance subcorpus. The graph in Figure 7.1. shows that loanwords (indicated by the blue line) are far more likely to be encountered than endogenous lexemes (orange line) for the concepts considered and that loanwords are relatively more frequent in policy-making instruments than in, e.g., books.

Figure 7.1. Probability of loanword versus endogenous lexeme across genres – Finance

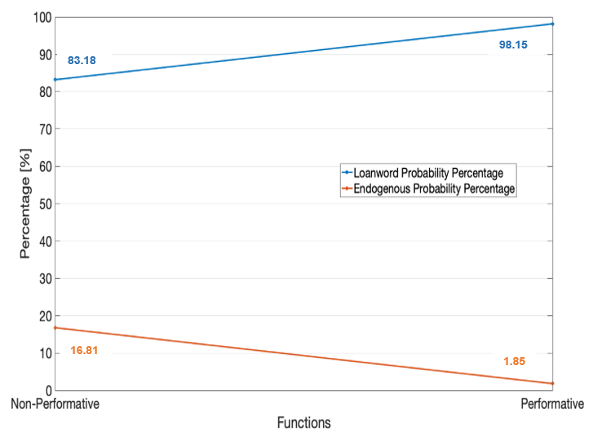

7.1.2 Probability percentages by function – finance

Figure 7.2. shows the probability percentages of having a loanword versus an endogenous lexeme across the different textual functions in the finance subcorpus. Again, loanwords (blue line) are far more likely to be encountered than endogenous lexemes (orange line) in general, and this trend is more prevalent in performative than in non-performative texts.

Figure 7.2. Probability of loanword versus endogenous lexeme across functions – Finance

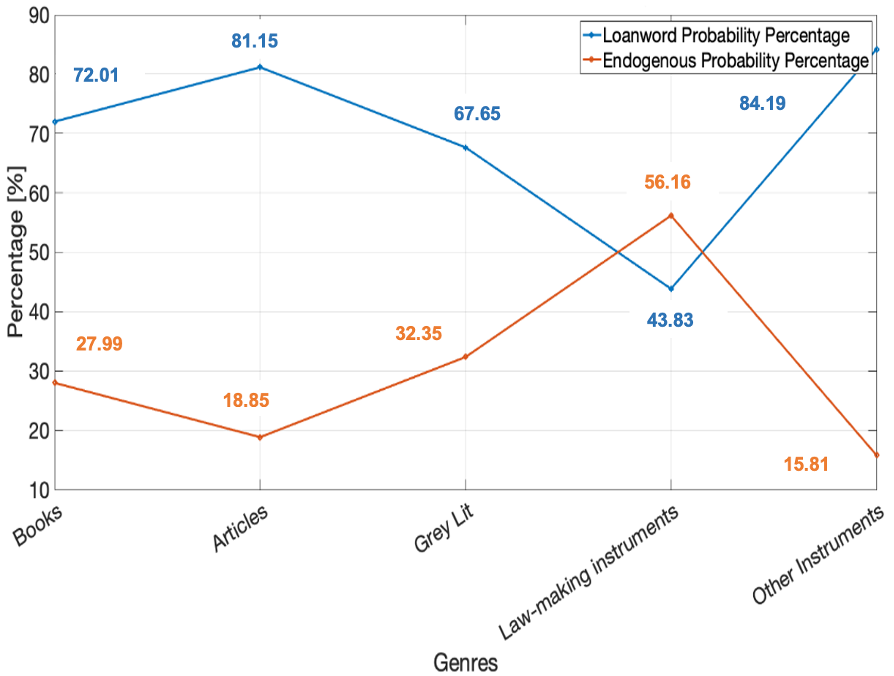

7.1.3 Probability percentages by genre – family law

Figure 7.3. shows the probability percentages of having a loanword versus an endogenous lexeme across the different genres. The graph in Figure 7.3. shows that loanwords (blue line) are far more likely to be encountered than endogenous lexemes (orange line) for the concepts considered in most genres (the exception being law-making instruments).

Figure 7.3. Probability of loanword versus endogenous lexeme across genres – Family Law

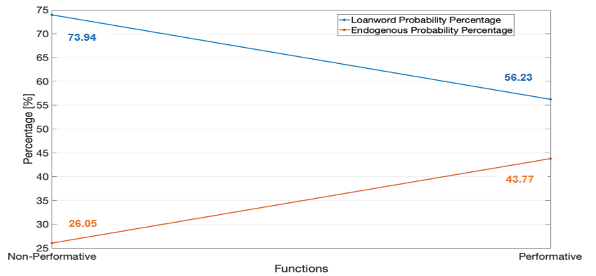

7.1.4 Probability percentages by function – family law

Figure 7.4. shows the probability percentages of having a loanword versus an endogenous lexeme across the different textual functions. Again, loanwords (Figure 7.4.) are more likely to be encountered than endogenous lexemes (orange line) in general, but this trend is more marked in non-performative than in performative texts.

Figure 7.4. Probability of loanword versus endogenous lexeme across functions – Family Law

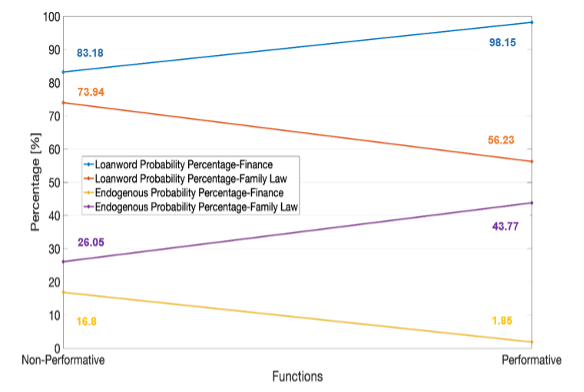

7.2 Function and genre as explanatory variables

The regression analysis of Islamic finance datasets shows that the explanatory variables ‘function’ and ‘genre’ are impactful. The textual function (performative versus non-performative function) has a notable impact on the choice between a loanword versus an endogenous lexeme. The performative function of the text seems to allow the use of loanwords on a larger scale given that the probability of having a loanword is higher in performative texts (98.15%) versus non-performative texts (83.18%). A possible interpretation is that performative texts (e.g., policy-making instruments and other instruments such as financial contracts, agreements, and application forms) opt for Arabic loanwords to attract the clients of the Islamic finance industry, who may find culture-specific or culturally tailored product labels appealing, particularly in the policy-making instruments issued by the regulatory bodies of the industry. By contrast, non-performative texts (book, articles, and grey literature) tend to use endogenous lexemes relatively more (with a probability percentage of 16.81% versus 1.85% in performative texts), which could indicate that the scholarly community is attempting to create endogenous English equivalents for Islamic concepts.

Results showed that the probability of having a loanword as opposed to an endogenous lexeme is very high across all genres of Islamic finance (Figure 7.1.). The loanword probability percentage starts from 76.43% in the genre of books and rises steadily, recording 92.76% in the grey literature genre and 93.67% in the academic articles genre. However, the loanword probability is at its highest in the performative genres of policy-making instruments and other instruments, scoring 98.19% and 98.07%, respectively. On the other hand, the endogenous lexeme probability records extremely low percentages of 1.81% and 1.93% across the performative genres of policy-making instruments and other instruments. The probability of having an endogenous lexeme increases slightly among the non-performative genres, recording 6.32% in articles and 7.24% in grey literature, while it is highest in the genre of books (23.56%). Accordingly, inter-genre differences can also be observed. For instance, books tend to rely less on loanwords compared to other genres. In other words, endogenous lexemes are more likely to occur in the genre of books, indicating the scholarly efforts towards bridging terminological gaps. By contrast, both genres of policy-making instruments and other instruments show lower reliance on endogenous lexemes and consequently greater preference for loanwords, thus reflecting the business market and industry norms.

On the other hand, the regression analysis of the family law datasets shows that the textual function moderately impacts lexical variation. Here, the non-performative category is more likely to employ loanwords (73.94%) than the performative category (56.23%). Conversely, the performative category tends to accommodate endogenous lexemes (43.77%) better than the non-performative category (26.05%). Hence, the producers of scholarly and reference works on Islamic family law seem to have more freedom about retaining iconic Islamic loanwords than lawmakers who must abide by the principles of communication and intelligibility imparted by endogenous lexemes.

Nevertheless, findings also corroborate the influence of genres and their communicative purposes in shaping lexical choices within family law. Of particular interest here are the genres of law-making instruments and other instruments, which both fall within the performative category; whereas the former had the lowest intra-genre probability percentage for the loanword at 43.83%, the latter showed the loanword probability is its highest (84.19%). Such divergence can be interpreted from the point of view of reception (i.e., the intended audience). Law-making instruments such as codes and laws are produced for broader audiences, therefore their communicative purpose is to make the law intelligible and easily accessible by limiting the use of loanwords in favour of the more informative endogenous lexemes. Accordingly, the endogenous lexeme had a high probability of 56.16% in law-making instruments compared to 27.99%, 32.35%, 18.85%, and 15.81% in the other genres of books, grey literature, articles, and other instruments, respectively. By contrast, the increased use of loanwords in the genre of other instruments (84.19%), which is comprised of private law contracts (e.g., marriage and divorce), petitions, and court documents, could be due to the narrower audience addressed by this genre. Hypothetically, private law contracts are meant to serve the documentation of Muslim populations, while court materials are oriented towards specialist legal audiences. In situations involving communication with courts, Šarčević (2000) holds that the policy of translating culture-bound issues is generally tailored to initiate an effective interaction between the translator and the judiciary. In this regard, the use of loanwords is the most legitimate technique of translating concepts that are peculiar to a given national legal system in order to identify the law according to which such culture-specific concepts will be interpreted. Šarčević argues that where the translator borrows a loanword from the source culture, the judge or legal specialist is thereby alerted to the fact that this particular concept is elaborated elsewhere under another foreign legal system (ibid, pp. 7-9). In line with Šarčević’s argument, if an English translation employs the Arabic loanword ʿidda, the translator would be guiding the judiciary to refer to Islamic Law where this concept is articulated to denote the three-or-four month period during which a woman shall not remarry another man after her divorce or the death of her former husband. Hence, the high loanword probability in the genre of other instruments is intended to locate the concept in its cultural background when required for addressing specific audiences.

Overall, inter-genre differences can be inferred within each of the textual function categories. Within family law, the non-performative genres of articles and books employ loanwords to a greater extent (81.15% and 72.01%, respectively) than grey literature (67.65%). Consequently, grey literature tends to use endogenous lexemes (32.35%) more than books (27.99%) and articles (18.85%). Within the performative category, however, other instruments rely on loanwords (84.19%) considerably more than law-making instruments (43.83%). Endogenous lexemes, in contrast, are more typical of law-making instruments (56.16%) compared to other instruments (15.81%). Within finance, the non-performative genres of articles and grey literature rely more on loanwords (93.67% and 92.76%, respectively) than books (76.43%). This means that endogenous lexemes are relatively more frequent in books (23.56%) than in articles and grey literature (6.32% and 7.24%, respectively). Differences are, however, insignificant among the genres of the performative category in Islamic finance.

7.3 Subject field as an explanatory variable

Subject field is an independent variable that reveals distinctions between finance and family law in their handling of culture-specific concepts (Figures 7.5. and 7.6.). Based on the corpus linguistic analysis, Islamic finance is found to be more reliant on loanwords, supplementations and lexical expansions compared to family law, providing evidence that Islamic finance is more culture-bound since its concepts are sufficiently different from the conventional system.

Figure 7.5. Measuring subject field as an independent variable - Probability of loanword versus endogenous lexeme across functions – Finance vs. Family Law

Figure 7.6. Measuring subject field as an independent variable - Probability of loanword versus endogenous lexeme across genres – Finance vs. Family Law

Inter-subject field difference can be revalidated from the results of the regression analysis. The loanword probability percentages are higher in finance than in family law. Within finance, loanwords are more typical of performative texts (98.15%) than non-performative texts (83.18%) — yet both percentages are high. By contrast, within family law, the occurrence of loanwords in performative texts (56.23%) is lower than in non-performative texts (73.94%) — yet both percentages are lower than those in finance. By way of contrast, Islamic family law is more tolerant of endogenous lexemes than Islamic finance. The probability of endogenous lexemes recorded 43.77% and 26.05% in the performative and non-performative categories of family law, respectively, versus the lower percentages of 16.81% and 1.85% in the non-performative and performative categories of finance.

What is at stake here is that the textual function and subject field are not mutually exclusive; instead, they go hand in hand in determining lexical choices. This is because the different genres that make up the functional categories under each subject field may have their own specific conventions (Figure 7.6.). For instance, the law-making instruments genre in family law can have conventions that are different from its counterpart policy-making instrument genre in finance. Law-making instruments in family law are more legally binding in terms of law enforcement than their counterpart policy-making instruments, which regulate a financial industry rather than stipulating individual rights and obligations. Therefore, for the sake of gaining wider outreach and for avoiding ambiguity, family law-making instruments can be more receptive of endogenous lexemes than their financial counterpart. The probability of having endogenous lexemes thus recorded 56.16% in family law-making instruments versus 1.81% in Islamic finance policy-making instruments. In summary, ‘textual function’, ‘genre’ and ‘subject field’ acted as three distinct but also interrelated fundamental independent variables that influence linguistic choices and lexical norms.

8. Conclusion

The main aim of this empirical study was to explore the lexical features of the English-language discourse on Islamic law by triangulating corpus methods and statistical logistic regression modelling in line with the currently sought-after methodological pluralism in empirical translation studies. The study established the connection between Islamic finance and family law as a unique discourse on Islamic law and sought to uncover the linguistic norms underlying this discourse, which has a technical nature, yet is imbued with cultural significance. The research was designed to determine the effect of contextual factors (‘genre’, ‘function’, and ‘subject field’) on lexical variation in this discourse. The analysis of Islamic legal discourse contributes to debates on translation and cultural representation by proposing an approach that seeks to reconcile the “reductive binaries” of source-oriented versus target-oriented techniques, as criticised by Merrill (2020, p. 432). This reconciliatory approach can be observed from the behaviour of loanwords and endogenous lexemes, which tended to co-occur in the various forms of cluster techniques (couplet, triplet, and quadruplets). In the terminology of linguistics, the behaviour of Arabic loanwords versus English endogenous lexemes in the current study is typical of ‘distributional equivalence’, which describes the linguistic phenomenon where linguistic items “occur in the same range of contexts” (Malmkjær, 2002, p. 256). Accordingly, the current research shines new light on the idea of lexical variation, arguing that it is not a case of pure competition between Islamic and English lexis; rather, there are synergies between the two poles since the collocation between the loanwords and endogenous variants is a characteristic of the hybrid discourse of Islamic law. Such synergies reveal perspectives about the behaviour of loanwords, which relate to the scope of “loanword research” (Zenner & Kristiansen, 2014, pp. 1-5) and understanding of the borrowing process.

Acknowledgements/Funding

This research project was funded by Dublin City University’s School of Applied Language and Intercultural Studies, and the Irish Research Council under the Government of Ireland Postgraduate Scholarship, reference number GOIPG/2021/457.

References

Alcaraz Varó, E., & Brian, H. (2002). Legal translation explained. St Jerome.

Baker, P. (2006). Using corpora in discourse analysis. Continuum.

Bhatia, V. (2013). Analysing genre: Language use in professional settings (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Biel, Ł. (2014). The textual fit of translated EU law: A corpus-based study of deontic modality. The Translator, 20(3), 332–355. https://doi-org.dcu.idm.oclc.org/10.1080/13556509.2014.909675

Biel, Ł. (2022). Research into legal translation: An overview of the 2010s trends from the perspective of translation studies. In A. Parise, & O. Moréteau (Eds.), Maastricht Law Series. Comparative perspectives on law and language (pp. 59-73). Eleven.

Brezina, V. (2018). Statistics in corpus linguistics: A practical guide. Cambridge University Press.

De Sutter, G., & Lefer, M. (2020). On the need for a new research agenda for corpus-based translation studies: A multi-methodological, multifactorial and interdisciplinary approach. Perspectives, 28(1), 1-23. https://doi-org.dcu.idm.oclc.org/10.1080/0907676X.2019.1611891

Delaere, I., & De Sutter, G. (2017). Variability of English loanword use in Belgian Dutch translations: Measuring the effect of source language and register. In G. De Sutter, M. Lefer, & I. Delaere (Eds.), Empirical translation studies: New methodological and theoretical traditions (pp. 81-112). De Gruyter Mouton.

Doczekalsa, A., & Biel, Ł. (2022). Interlingual, intralingual and intersemiotic translation in law. In K. Marais (Ed.), Translation beyond translation studies (pp. 99-118). Bloomsbury Publishing.

Freixa, J. ( 2006). Causes of denominative variation in terminology: A typology proposal. Terminology. International Journal of Theoretical and Applied Issues in Specialized Communication, 12(1), 51-77. https://doi.org/10.1075/term.12.1.04fre

Hellman, A. (2016). The convergence of international human rights and Sharia law: Can international ideals and Muslim religious law coexist?. New York State Bar Association. https://nysba.org/NYSBA/Sections/International/Awards/2016%20Pergam%20Writing%20Competition/submissions/Hellmann%20Ashlea.pdf

Hu, K. (2016). Introducing corpus-based translation studies. Springer.

Jakobson, R. (2000 /1959). On linguistic aspects of translation. In L. Venuti (Ed.), The translation studies reader (pp. 113-118). Routledge.

Kettell, B. (2010). Islamic finance in a nutshell: A guide for non-specialists. John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Kilgarriff, A., Baisa, V., Bušta, J., Jakubíček, M., Kovář, V., Michelfeit, J., Rychlý, P., & Suchomel, V. (2014). The Sketch Engine: Ten years on. Lexicography, 1(1), 7-36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40607-014-0009-9

Kuriačková, I. (2018). Translation of culture specific terms in the EU legislative documents. [Master Thesis, Université du Luxembourg]. https://www.readkong.com/page/master-in-learning-and-communication-in-multilingual-and-6273846

Lexical Computing Ltd. (2015). Statistics used in the Sketch Engine. https://www.sketchengine.eu/documentation/statistics-used-in-sketch-engine/#KeyWords

Malmkjær, K. (2002). The linguistics encyclopedia (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Měchura, M., & Ó Raghallaigh, Ó. B. (2021). Introducing Terminologue: A cloud-based, open-source terminology management tool. EURALEX Proceedings. Democritus University of Thrace, Alexandroupolis, Greece, 7-9 September 2021. Thrace: SynMorPhoSe Lab, Democritus University of Thrace, 797-800. https://euralex.org/wp-content/themes/euralex/proceedings/Euralex%202020-2021/EURALEX2020-2021_Vol2-p797-800.pdf

Merrill, C. (2020). Postcolonialism. In M. Baker, & G. Saldanha (Eds.), Routledge encyclopedia of translation studies (3rd ed.) (pp. 428-432). Routledge.

Peruzzo, K. (2019). When international case-law meets national law: A corpus-based study on Italian system-bound loan words in ECtHR judgments. Translation Spaces, 8(1), 12-38. https://doi.org/10.1075/ts.00011.per

Prieto Ramos, F. (2014). Parameters for problem-solving in legal translation: Implications for legal lexicography and institutional terminology management. In L. Cheng, K. K. Sin, & A. Wagner (Eds.), The Ashgate handbook of legal translation (pp. 121–134). Ashgate Publishing Limited.

Prieto Ramos, F. (2019). Implications of text categorisation for corpus-based legal translation research: The case of international. In Ł. Biel, J. Engberg, R. M. Ruano, & V. Sosoni (Eds.), Research methods in legal translation and interpreting: Crossing methodological boundaries (pp. 29-47). Routledge.

Pym, A. (2014). Exploring translation theories (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Saldanha, G., & O’Brien, S. (2014). Research methodologies in translation studies. Routledge.

Santalahti, M., & Mikhailov, M. (2019). Language of treaties – language of power relations?. In Ł. Biel, J. Engberg, R. M. Ruano, & V. Sosoni (Eds.), Research methods in legal translation and interpreting: Crossing methodological boundaries (pp. 66-80). Routledge.

Šarčević, S. (1985). Translation of culture-bound terms in laws. Multilingua, 4(3), 127-133. https://doi.org/10.1515/mult.1985.4.3.127

Šarčević, S. (1989). Conceptual dictionaries for translation in the field of law. International Journal of Lexicography, 2(4), 277-293. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijl/2.4.277

Speelman, D., Grondelaers, S., & Geeraerts, D. (2003). Profile-based linguistic uniformity as a generic method for comparing language varieties. Computers and the Humanities, 37(3), 317–337. https://doi-org.dcu.idm.oclc.org/10.1023/A:1025019216574

The MathWorks Inc. (2022). Statistics and Machine Learning Toolbox. https://www.mathworks.com/help/stats/index.html

Vigier, F., & Sánchez, M. D. M. (2017). Using parallel corpora to study the translation of legal system-bound terms: The case of names of English and Spanish courts. In R. Mitkov (Ed.), Computational and corpus-based phraseology (pp. 260-273). Springer. https://link-springer-com.dcu.idm.oclc.org/book/10.1007/978-3-319-69805-2

Weston, M. (1991). An English reader’s guide to the French legal system. Berg.

Wolf, M. (2007). Introduction: The emergence of a sociology of translation. In M. Wolf, & A. Fukari (Eds.), Constructing a sociology of translation (pp. 1-36). John Benjamins.

Zenner, E., & Kristiansen, G. (2014). New perspectives on lexical borrowing: Onomasiological, methodological and phraseological innovations. De Gruyter Mouton.

Websites

The Islamic Law/Finance Termbase can be accessed via the following link: https://www.terminologue.org/IslamicLaw/

Data availability statement

The full data set is available in the following open repository:

Roshdy, R. (2023). Translating Islamic Law: the postcolonial quest for minority representation. [Doctoral dissertation, Dublin City University]. DCU Online Research Access Service DORAS. https://doras.dcu.ie/28896/

ORCID 0000-0003-1313-6882; e-mail: dr.ranaroshdy@gmail.com↩︎

Notes

The corpus may be accessed by sending an email request to the corpus developers (@ dr.ranaroshdy@gmail.com; dorothy.kenny@dcu.ie). However, future users will have limited access that grants a read-only privilege to search the corpus, but with restrictions to preview or download full texts.↩︎

The study follows IJMES transliteration system for Arabic words; the use of square bracket is a typographical convention to distinguish the concept from the loanword.↩︎

For the sake of readability, the following abbreviations are used for translation techniques: Adapt (Adaptation), Des (Descriptive substitute), Expan (Lexical expansion), Loan (Loanword), Neo (Neologism), and Supp (Supplementation).↩︎