“Guidance but not the ultimate commandment”: Pros and Cons of Using Pivot Templates in the Audio Description Production Workflow

Anna Jankowska1, University of Antwerp

ABSTRACT

The need for audio-described audiovisual content is mainly growing due to statutory accessibility required in many countries. Regrettably, despite the popular and legal demand for audio description, broadcasters and producers perceive audio description (AD) as an expensive service with little profit potential. Audio Description Translation (ADT) is an alternative production model that can reduce the time and costs involved in AD production while maintaining quality and increasing the availability of audio-described content in multiple languages. Drawing on a widespread practice of using (pivot) templates in modern subtitling workflows, this article investigates the use of pivot templates in audio description, focusing on the advantages and disadvantages of this production model as perceived by audio description translators. Data was collected in an experiment where six participants, five subtitlers, and an audio describer were asked to translate audio descriptions for Spanish films into Polish via an English pivot template. Results based on the thematic analysis of post-task interviews identify two main advantages: (1) personal advantages for the professionals performing the task and (2) external advantages that can benefit, for example, the production workflow, product, and target audience. The personal advantages are reduced time, effort, and responsibility. The external advantages are enhanced script quality and consistency.

KEYWORDS

Audio description, pivot translation, templates, production models, accessibility.

1. Introduction

Audio description (AD) is an accessibility service that verbally describes an audiovisual product's key visual elements. In media work, such as movies or television production, it is an additional audio track inserted in the natural pauses between the dialogues and significant sound effects. In recent years, following the adoption of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (2006), legal regulations requiring AD provision were introduced on national and/or regional levels in some countries. For example, many EU Member States require statutory AD from public and private broadcasters (European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2014) due to the Audiovisual Media Service Directive (Directive 2010/13/EU) and the so-called European Accessibility Act (Directive (EU) 2019/882). AD is required by law beyond the EU, for example, in Canada (Broadcasting Regulatory Policy CRTC 2015-104), the United States (Twenty-First Century Communications and Video Accessibility Act of 2010) and the United Kingdom (The Audiovisual Media Services Regulations 2014). Other countries worldwide are also developing both AD practice and legislative frameworks to implement it (for an overview, see Taylor & Perego, 2022).

Even though, as Romero Fresco (2013, 2019) points out, only 0.1% - 1% of revenue obtained by the top-grossing Hollywood films is spent on audiovisual translation and media accessibility, broadcasters, producers, and distributors often see AD as "a costly service with no revenue potential" (Plaza, 2017, p. 1). For this reason, in recent years, attempts have been made to propose solutions to increase AD's cost-efficiency. They can be roughly divided into two types of approaches. On the one hand, it is suggested that the revenue potential of AD users, who currently are thought to primarily be persons with visual impairment, could be expanded by including additional audiences, for example, persons with learning difficulties, cognitive impairments, and autism spectrum but also viewers without impairments (Mazur, 2020; Starr, 2022). On the other hand, changes to current workflows and production models are suggested, such as replacing human voicers with text-to-speech voicing (Szarkowska, 2011) or moving AD production from post- to pre-production and producing AD in-house rather than outsourcing it, which so far does not seem to significantly contribute to cost-efficiency (Plaza, 2017; Sade et al., 2011). Limited research investigates applying AI-driven solutions to scripting AD and concludes that this is not a feasible alternative (Braun & Starr, 2019, 2022; Starr et al., 2020).

One of the suggested changes to the current workflows, particularly to the AD script production stage, is audio description translation (ADT), which consists of translating existing audio descriptions into multiple languages. While ADT was suggested as an alternative AD script production workflow very early on in research on AD carried out within the scope of audiovisual translation and media accessibility (López Vera, 2006; Matamala, 2006; Orero, 2007), it has so far not received much scholarly attention and is not yet widely used in the media localisation industry (S. Yousaf, 2018, in personal communication), which stands in stark contrast to modern subtitling workflows where templates and pivot templates are widely used to simultaneously provide subtitles in various languages (Georgakopoulou, 2019; Kapsaskis, 2011; Nikolić, 2015; Oziemblewska & Szarkowska, 2022).

The contribution of this paper is that it investigates implementing pivot templates into the AD production workflow to improve the sustainability of AD, which, in turn, can increase the availability of this access service. This paper, in particular, discusses the advantages and challenges of this workflow and the different features of AD pivot templates as seen by audio description translators who, if pivot templates are implemented, will be essential actors in the AD value chain. Translators' attitudes are crucial to integrating templates into the workflow, as shown by the subtitlers' broad disapproval of templates when they were first introduced (Oziemblewska & Szarkowska, 2022).

2. Audio description translation

The concept of ADT is simple: it involves translating pre-existing audio descriptions into different languages (López Vera, 2006). On the one hand, as ADT omits certain stages of the AD script creation workflow, it is suggested to be both faster and, thus, more cost-efficient (Jankowska, 2015). On the other hand, the envisaged benefits of ADT are also maintaining quality and avoiding cultural loss (Jankowska, 2015; Jankowska et al., 2017; López Vera, 2006; Matamala, 2006; Oncins, 2022; Orero, 2007; Remael & Vercauteren, 2010).

So far, only some of these possible benefits have been empirically tested, i.e., overall feasibility, acceptance by target audiences, and time efficacy (Fernández-Torné & Matamala, 2016; Herrador Molina, 2006; Jankowska, 2015; López Vera, 2006; Remael & Vercauteren, 2010). From the limited studies carried out so far, it appears that ADT is feasible and, most importantly, accepted by the target users; however, the translated scripts must be adapted to fit the local AD conventions and meet synchronicity requirements (Herrador Molina, 2006; Jankowska, 2015). When it comes to time efficacy – research results are inconclusive, pointing to increased time efficacy (Jankowska, 2015) or no significant difference between writing from scratch and translating (Fernández Torné, 2016; López Vera, 2006). Cost-efficiency has so far not been confirmed or even researched. The common denominator of all these studies is that they investigated translating AD from English to other languages and used AD scripts or transcriptions of pre-recorded ADs rather than templates commonly used in subtitling (for an overview of templates, see section 3).

When it comes to professional practice, the introduction of ADT was met with initial criticism (Hyks, 2005), and to date, it has been mainly used to provide AD and/or train describers in countries with emerging access services where professional describers are more challenging to find (Georgakopoulou, 2009; Remael & Vercauteren, 2010; S. Yousaf, personal communication, 2016 and 2018;). The limited use of templates in audio description is a surprising finding, considering their widespread use in subtitling. However, this can be attributed to the current market practice within the audio description industry. Audio description services are rarely ordered in large quantities for multiple languages. Instead, smaller companies typically produce them locally, often with the support of non-governmental organisations (NGOs).

3. Translation templates in the audiovisual translation industry

In subtitling, templates and pivot templates are commonly used. This method simplifies the process by generating time codes for subtitles just once instead of doing it every time a movie is translated into a different language. Subtitling templates take many forms and names (for an overview of subtitling template types, see Nikolić, 2015). They can be as simple as empty time codes, also known as blank templates, which are subtitle files containing only each subtitle's start and end times. More complete templates, apart from spotting, also include a verbatim or condensed transcription of the dialogues. Lastly, the most intricate templates encompass both on-screen text and annotations, which serve as explanatory notes for translators to aid their understanding of the original dialogue. This proves particularly valuable when the source material contains elements such as slang, dialects, irony, wordplay, culture-specific references, and other linguistic complexities that may pose challenges for non-native speakers to comprehend accurately (Georgakopoulou, 2006, 2019). Following the expansion of global streaming services, the latter is currently the most widely used type of subtitling template.

The language of the templates usually matches the source language of the associated audiovisual content (e.g., an English template for an English-speaking film). However, global Language Service Providers (LSPs) rely heavily on pivot language templates, which use an intermediary language (Alvarez Ortiz, 2019). For example, an English language template is created for a Polish film, and subtitles are translated from English into various languages using this time coded file template.

In response to the rapid increase in demand for multilingual subtitles brought about by the emergence of the DVD industry, templates were introduced in the mid-1990s as the prevailing approach in multilingual subtitling workflows. (Artegiani & Kapsaskis, 2014; Georgakopoulou, 2006, 2019). Templates allowed for a more efficient and effective multilingual subtitling production workflow and facilitated standardisation, consistency, accuracy, and quality assurance across multiple languages (Artegiani & Kapsaskis, 2014; Georgakopoulou, 2006, 2019). Nevertheless, the industry's most notable benefit stemmed from cost-efficiency, primarily achieved by eliminating redundant work through the spotting process, which is now done and paid for only once. Additionally, this approach reduced subtitlers' fees, as they found themselves solely responsible for translation rather than the entire process (Nikolić, 2015; Oziemblewska & Szarkowska, 2022).

Subtitlers welcomed templates with far less enthusiasm. The core of their concerns was what Díaz Cintas (2001) described as "the excessive atomisation of the profession with the unfruitful and unnecessary split between translators, spotters, subtitlers, adaptors, etc." which, in the subtitlers' view, contributed to the worsening of their working conditions, degraded their profession and affected the quality of subtitles (Artegiani & Kapsaskis, 2014; Nikolic, 2015; Szarkowska, 2016; Oziemblewska & Szarkowska 2022).

All in all, while templates have had adverse effects on the profession and are still a hot topic in translator-industry debates, they have also revolutionised the field and, as noted by Artegiani and Kapsaskis (2014, p. 433), "are, for better or worse, a key structural feature of the way the contemporary subtitling industry operates."

4. Overview of the current study

This article is part of a larger study which explores the feasibility of implementing pivot templates into the audio description production process by looking into both the process and the product. This article focuses on the advantages and challenges of this workflow as perceived by the professionals who would possibly be involved in it. The quality of AD created from scratch versus AD created via the ADPT workflow is addressed in other publications (e.g., Jankowska, 2023).

4.1. Participants

A total of six professional translators with (n = 4) and without (n = 2) experience/training in audio description took part in the study. One of the people involved was a professional audio describer. Two participants received AD training in audiovisual translation as part of their university programs, and one took a brief vocational course. The other two participants had heard of audio description but had never received any formal AD instruction or had any practice.

The number of years the participants had worked in the audiovisual translation industry ranged from two to 15 years, with a mean of 8 (SD = 4.89). Their weekly average of translated AV content in the last 12 months ranged from below one hour to 20 hours, with a mean of 6.41 (SD = 7.05).

The professionals were recruited via a Facebook group for professional AVT translators and worked with the English-Polish language combination. They did not know the Spanish language or culture. Participants were remunerated for taking part in the experiment. The Ethics Committee of the University of Antwerp approved the study.

4.2. Materials and software

This study used clips from a previous project looking into describers’ processes when dealing with foreign films (see Jankowska, 2021). The clips were extracted from films set in Spain (see Table 1). They were manipulated so that they contained a high concentration of culture-specific references. However, they remained a narratively coherent sequence of scenes. As in the previous study, the clips were presented with no dialogue and sound to guarantee a comparable amount of time to insert audio descriptions. The mean duration of the clips was 63 seconds.

| Title | Director / Year | Genre |

|---|---|---|

| Dieta mediterránea | J. Oristrell (2009) | comedy/romance |

| Ocho apellidos catalanes | E. Martínez-Lázaro (2015) | comedy/romance |

| Vicky, Cristina, Barcelona | W. Allen (2008) | comedy/drama/romance |

| 18 Comidas | J. Coira (2010) | comedy/drama |

Table 1. Films used in the experiment.

Each participant was asked to translate AD for five clips into Polish via an English pivot template. The English pivot templates were created based on audio descriptions of the clips prepared in Spanish by describers from Spain in the previous experiment (see Jankowska, 2021).

Participants worked in a cloud-based AD authoring tool, Frazier2, which enables describers to write and cue the AD script and preview it against the original video with text-to-speech (see Figure 1), which can be set at five different reading speeds (normal, fast, faster, experimental +50% and experimental +100%)3. Frazier integrates AI-based machine translation technology, allowing for direct translation in the software.

Figure 1. Frazier set-up for the experiment.

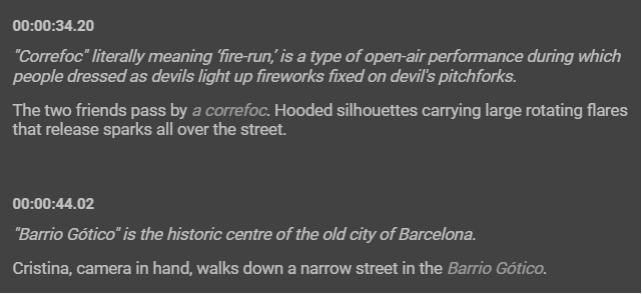

Following current mainstream subtitling practices (Netflix, 2021b) and recommendations (Oziemblewska & Szarkowska, 2022), templates were spotted, and foreign cultural words were not localised but signalled with italics and kept as in the source language with annotations inserted above the AD text to explain them (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Culture-specific references and annotations in AD pivot template.

The template was unlocked4 so that participants could modify it as they saw fit: they could remove/add content and adjust the spotting. Regarding the reading speed, they were instructed not to use the experimental rates, thus limiting their settings to normal, fast, and faster.

4.3. Procedure

Before the experiment, participants were asked to read the Netflix AD style guide (2021a) and watch two instructional videos on strategies to audio describe culture-specific references (ADLAB PRO, 2019a, 2019b).

Participants worked from home, using their equipment, and were monitored remotely via MS Teams – their screen and computer sound were recorded, and the researcher was available to assist them when needed. They were allowed to use the Internet and the built-in AI machine-translation feature. No time limit was set. The procedure lasted about 3–4 hours and was divided into three stages:

In the first stage, the procedure was presented to participants, and any questions they had about it were answered. This was followed by a short training session using the software. Since Frazier is very similar to cloud-based subtitling software, participants, who all had subtitling experience, did not find it challenging.

In the second stage, participants received a file with a short description of each clip to give them the scene's context and proceeded to translate the ADs. The clips were assigned to participants in random order.

Upon completing all the translations, participants were invited to engage in a semi-structured post-task interview in Polish5, comprised of two parts. In the initial segment, open-ended questions sought participants' opinions on the task's difficulty level, experience with the template and translation process, strengths and weaknesses of using templates to create AD and potential workflow enhancements. Participants also contemplated how their performance might differ when creating audio descriptions from scratch, addressing the process and the resulting product. The interview delved into the significance of annotations for culture-specific references, exploring their contribution, perceived benefits, and areas for improvement. Participants concluded the first part by sharing their motivations for using machine translation. Participants elaborated on their specific translation choices in the second part, utilising their translations as prompts.

5. Findings

The recordings were transcribed using the MS Teams automatic transcription module and revised within 48 hours of the interviews. Then, a thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) was conducted using NVivo. Following the thematic analysis results, the issues discussed in the interviews were grouped into task difficulty, template advantages and challenges, and template and software features. They are used below as a framework to present the results.

5.1. Task difficulty

Overall, participants in the study expressed a positive attitude toward working with the template in the audio description translation process. One participant (PL02) said they "honestly liked working with the template.” Participants found the level of challenge to be appropriately balanced, allowing for active engagement and the use of their judgment and creativity. This balance was seen as crucial, preventing the task from becoming overwhelming while providing a stimulating and satisfying experience.

The underlying theme was culture-specific references. Participants consistently regarded this aspect as the most challenging task throughout the study. However, they expressed notable satisfaction with signalling and explaining culture-specific references within the pivot template. This aligns with the specific design and objectives of the study, further validating its intended purpose.

5.2. Template advantages and challenges

The thematic analysis of the post-task interviews revealed that participants have overall optimistic attitudes towards AD pivot templates (see Table 2), evidenced by considerable accounts of the advantages.

Advantages of templates (mean % of interview data) |

Disadvantages of templates (mean % of interview data) |

|---|---|

| 10% | 2% |

Table 2. Percentage of interview data covered by account

of advantages and disadvantages of templates.

While all participants (n=6) discussed the advantages of templates, only some (n=3) briefly mentioned the possible challenges but did not engage with the topic. However, given the aim of this study, the challenges mentioned by participants are also included in the discussion of the results. It is also essential to note that, as the participants themselves admitted, they were not audio description experts and may not have addressed all issues. In exploring both advantages and challenges, participants drew from their immediate experiment experiences and their professional backgrounds in audiovisual translation, where templates and pivot templates are widely used.

5.2.1. Template advantages

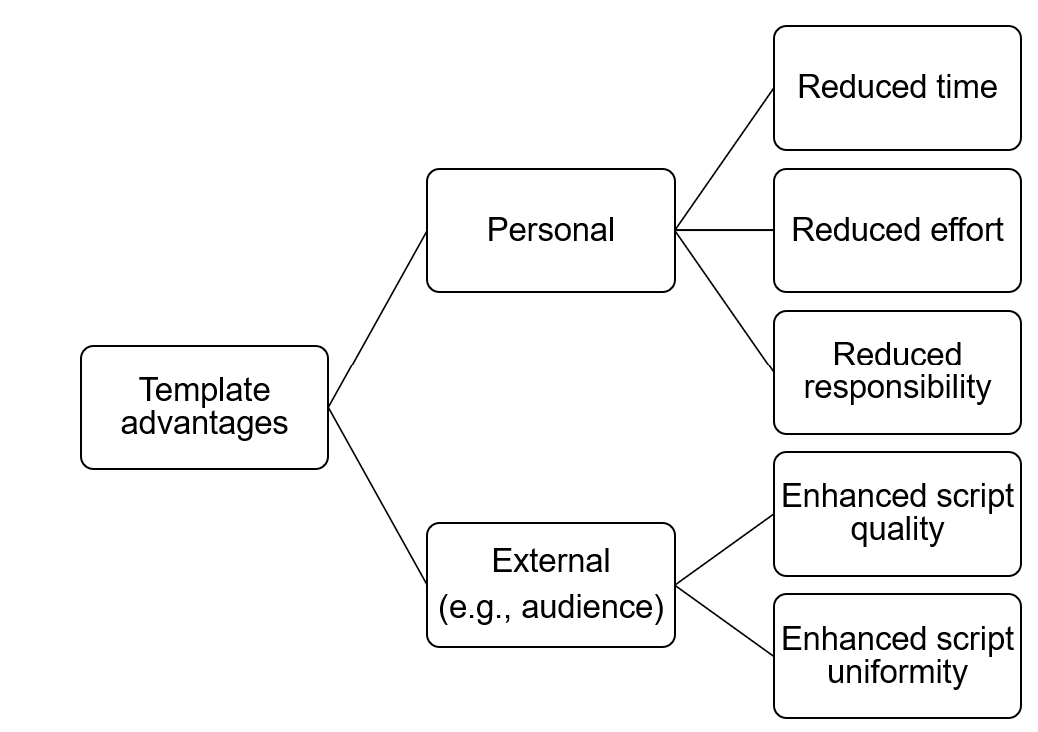

The advantages mentioned by the participants can be attributed to two main categories: personal advantages for the professionals performing the task and external advantages that can benefit the product and the target audience (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Advantages of audio description pivot templates (interviews).

5.2.1.1. Personal advantages

The main personal advantages were reduced time, effort, and responsibility since decisions about when, what, and how to describe had already been made. As one of the participants noticed:

It seems to me that if I had to do it from scratch, that is, if I had to watch the video and I had to write the audio description myself, I think it would be much more difficult; it would require much more creativity and also much more effort. (PL02)6

While participants see these advantages as interconnected, the mean percentage coverage of interviews shows that the time reduction was the most important advantage. The importance that participants attributed to time efficacy was perhaps best motivated by one of the participants who said:

[…] Good solutions are those that speed up our work. The cost of everything is going up, and with the current AVT rates, you either work quickly and well, or you won't make a living. (PL05)

Participants pointed out that the workflow being tested facilitated three significant tasks: cueing, content selection and information searching. All participants agreed that templates saved them time as they did not have to "do the entire cueing" (PL05), which saved them the actual work of checking where and how much space there is to insert audio description. Instead, they could "accept or modify the pre-existing time code" (PL05). As one of the participants noticed:

As with subtitles, you don't need to cue it yourself. The timing suggestions are already there. I can use them as they are or adjust them a bit... This is super convenient. (PL05)

In addition, participants observed that working with blank templates would already be advantageous since "having the time codes alone would save the time needed to identify those moments in the film where AD events can be inserted" (PL04).

Participants mentioned that the pre-selection of visual content significantly reduced the time, effort and responsibility involved in the task as they did not need to make those decisions themselves. Comments included:

The advantage is that you can immediately see if someone does not know what to focus on… it is already said. It's in this template. Someone wrote it… pointed it out. [...] If I can't make up my mind, then someone has already done it this way or that way in the template. They decided that something needed to be emphasised. (PL01)

One participant also noted that templates could save additional time during the quality assurance phase because translators would not be required to "explain their decisions to quality control" (PL05).

Last but not least, the participants were convinced that the annotations provided for culture-specific references substantially reduced the research time. Comments included:

These explanations... make it incredibly easy because they cut down on time spent dabbling on what to do, and also, this extra information reduces googling. (PL01)

Annotations made my job easier. It would be great if something like this was standard. […] Because it shortens the work a lot. It reduces the effort. (PL04)

I think the annotations were very helpful because if it wasn't for them, this task would have taken me twice as long. (PL05)

Annotations were very helpful and generally saved a lot of time. It's the same as in the good subtitling templates. The culture-specific references and slang are explained. This is a huge help. Because otherwise, you have to look for it. If it wasn't for the annotations in the AD template, I would have to look up each of these words, which means my work process would get longer, and I would need to ask for a higher rate or earn less. (PL06)

5.2.1.2. External advantages

Regarding the external advantages, participants noticed that templates could benefit the AD script in two ways: they could enhance the script and increase its consistency in collaborative workflows.

Regarding script enhancement, participants noticed that templates helped them to introduce elements they would otherwise omit because they would not detect them or deem them irrelevant. Participants noticed that this advantage applied to culture-specific references (see section 5.3.2 for a detailed discussion) and elements lacking cultural specificity but relevant to the plot. Comments included:

I also have the impression that, through a template, the audio description can provide a richer experience for the audience […] Someone thought about it and selected specific elements out of the image. Thanks to that, one will pay attention to things or highlight some things that one wouldn't otherwise pay attention to. (PL01)

I didn't see certain details, and this template was even more helpful to me because there were references to certain things that I might not have noticed on my own. (PL04)

Regarding consistency, one participant noted that templates could be an efficient solution to maintain script uniformity in a collaborative workflow when, for example, two or more describers work simultaneously on a movie or series season to meet tight deadlines. As one of the participants noticed:

[…] In audio description, similar to translation, depending on who is writing and their experience, different things in the picture will draw their attention. So, yes, this is where differences will be present. With a template, in general, there will be fewer differences. Take a series, for example. Suppose you assign episodes to several audio describers who translate from a template. In that case, all the descriptions will be similar to each other. More similar than if you assign several describers and ask them to write from scratch. These descriptions would be very different. So, with a series, for example, templates will be a big advantage. (PL06)

5.2.2. Template challenges

While there was insufficient feedback on template challenges for a proper thematic analysis, participants’ comments can be broadly classified into content-related and workflow-related challenges.

5.2.2.1. Content-related challenges

The first group of comments revolved around how the use of templates can influence the content selection and structure of the final script. On the more general level, one of the participants noticed that translators might follow the template too closely, which could result in a script that is not fully adapted to the needs of the target audience:

The only disadvantage that I could see in such a template is combined with an advantage. Everything is handed on a platter, ready to use, and one can follow the template too closely if one is not careful, tired, or in a hurry. And in this way, one can lose the opportunity to add something, to expand the scene, maybe shorten some information to introduce something else, something more important to perceive the material fully. (PL01)

The participant with extensive experience in audio description observed that the template affected how they organised the information. Without it, they would “maybe not pay attention to different things, but would order them differently” (PL06).

Another potential challenge, according to the participants, is the quality of the templates – as one participant noted, the introduction of a template workflow will be effective only if the resulting audio description is, at a minimum, comparable in quality to the audio description created entirely from scratch.

We assume that someone who created this English template or translated it into English did it so well that we won't do it better. But in subtitling, template quality is often an issue. And it's bound to happen in audio description, too. (PL05)

5.2.2.2. Workflow-related challenges

One of the issues was whether the templates would be helpful for seasoned describers who might find it easier to write from scratch than to translate from a template. As commented by one of the participants:

Well, it seems to me that after years of experience with voice-over, it is simply that one's brain is already formatted in a certain way. The script itself acts as additional help, but one actually hears the dialogues and already knows exactly how to translate them, what will fit, and what needs to be left out [...] I have too little practice with audio description to decide. Still, if I were an experienced describer, it would be so natural for me to audio describe that maybe I would struggle more with the template… (PL05)

This doubt resonates well with the opinion expressed by the experienced describer, who declared that they would prefer to "write the script from scratch myself" (PL06). This describer also observed that relying on the duration of the available gap, they instinctively gauge the amount and type of information suitable for inclusion in the description:

When I'm working and, for example, I know that I have two seconds, three seconds, four seconds... Then I automatically know how many words or sentences I can... I can compose. Of course, then you have to check it, read it repeatedly, and see whether it fits. But it's instinctive and intuitive. (PL06)

One participant observed that pivot templates add another layer of complexity to a standard template workflow, as, according to them, introducing an intermediate language creates more opportunities for error:

The specifics of this transfer - that someone writes AD in Spanish, then someone translates it into English - is that it creates two platforms for errors. A Spanish-speaking describer may have omitted something obvious7. The English-language translator may not have fixed this in their translation, so it would be missing in the template. Well, then it's back to translating into the target language. Either that target describer will see it, has knowledge of the culture, and can, sort of, recover it from the original, from the image. Or they will not do that and will follow the template. Well, it is a bit like playing the telephone game. (PL05)

The same participant suggested that assigning pivot translation to translators familiar with the source video's language and culture is the best approach to this issue:

It is good when AD for a film from Spain is written by a person who knows something about this country. It would be best if they knew Spanish. Even if they get an English template, knowing Spanish, so having familiarity with the Spanish culture on some level higher than common knowledge, they will be able [...] to notice and improve this template, to move away from it. Because they will be able to stop and say: No, something important omitted here is worth adding. Or focus on something […]. So, the only remedy here is to know the culture you are to describe. (PL05)

The locking of templates was the issue that was brought up most frequently. All participants who discussed potential obstacles expressed their disapproval of the impossibility of editing both cueing and content, citing negative effects on the product's quality and the translators' working conditions. Comments included:

I liked that the duration could be changed. If it could not be done, that would frustrate me. Well, because I would have to shorten the text pointlessly. In some places, I needed to shorten it anyway. […] In fact, in subtitling, you often cannot change the time codes or the template. And well, this is really frustrating. (PL04)

5.3. Template and software features

During the interviews, I also asked the participants to comment on specific features of the template and software used: identification of culture-specific references, annotations used to explain them and machine translation.

5.3.1. Unlocked template

As already explained, templates used in the study were unlocked, and participants could modify both spotting and content. This was highly appreciated by all participants who, in general, felt that AD templates, just like any other templates used in the AVT industry, should be regarded as guidance and a starting point; one should not need to "translate it word for word" but should be able to "add something from oneself" (PL03) and to "omit, change and add" to bring out "what is important for the target audience" (PL02). As one of the participants summarised:

The AD template simply must be, by default, open with the possibility of making changes because the template is the starting point. All templates must be approached this way because it is... recreating based on someone else's work or idea. I would consider templates as facilitation, as guidance, but not as the ultimate commandment. (PL05)

What seemed particularly important for the participants was the “flexibility and freedom” (PL04) that working with an unlocked template gave them. They felt that it allowed them to “enjoy their work” (PL01) and “show their artistry and craftsmanship” (PL05).

While all participants were very vocal about the importance of unlocking the templates, one participant observed that it may not be a desirable solution if it comes at the expense of having to deal with additional, time-consuming tasks, as is frequently the case in subtitling when modifications to an unlocked template need to be explained and justified:

Let me start with the disadvantages. The main one is a stubborn and blockheaded client who, after the compliance check, requires you to explain every deviation from the template. [...] On the client's side, you need to trust the artist and say: OK, if you moved something in this template or added something, you do not have to write me an essay explaining why it was right. I trust you. (PL05)

5.3.2. Identification and explanation of culture-specific references

As mentioned, culture-specific references were not localised in the templates but kept as in the source audio description and explained in the annotations (see Table 3). Participants were overwhelmingly positive about identifying culture-specific references and annotations; the thematic analysis revealed that these two features were the most prominent aspect of AD templates for participants. In their opinion, these features resulted in personal and external advantages (for a more detailed discussion of opinions on introducing annotations in pivot AD templates, see Jankowska, 2023).

| Culture-specific reference | Annotation |

|---|---|

| Radiant Sofia and her friends pose in front of a paella. She is on Toni's shoulders, who playfully bites her finger. | ‘Paella’ is a traditional Spanish rice dish. |

| Another day, Sofia picks up a plate of sea urchins. She flips a tortilla. | ‘Tortilla’ or ‘tortilla de patatas’ is a traditional dish from Spain. It is an omelette made with eggs and potatoes, optionally including onion. |

| A group of costaleros stands outside a church. Rafa is among them. The men enter under a paso with a statue of the Virgin Mary surrounded by flowers and candles. | ‘Costaleros’ are porters of pasos in Seville. ‘Paso procesional’ is an elaborate float made for religious processions, often adorned with wooden statues of saints. |

| They stroll along the terrace of La Pedrera, between the trencadís towers and the chimneys crowned with warrior's helmets. | ‘Casa Milà’, also known as La Pedrera, is a modernist building by Antoni Gaudi. One of the landmarks of Barcelona. |

| At the door of another bar, a waitress offers pieces of tarta de Santiago to passers-by. | ‘Tarta de Santiago’ is an almond cake from Galicia originating in the Middle Ages and the Camino de Santiago. |

Table 3. Annotations explaining foreign cultural words in the pivot AD templates.

Participants found the identification of culture-specific references useful because “the mere fact that someone noticed and selected them from the image” (PL01) allowed them to include elements that they would “not notice on their own” (PL01) or “would not have guessed what they are” (PL02) which enhanced the quality of the script. As participants underlined, even “simply highlighting these elements in the text in italics immediately catches the eye” (PL05) and “giving the exact name and spelling makes it easier to find accurate information about it” (PL02).

Annotations which “explained the culture-specific reference right away” (PL05) were seen as even further help since they “gave enough context to understand what was going on” (PL02) and “what the term given in the template referred to” (PL04). This allowed the participants to shorten the time needed to understand and search for equivalents because they only looked for information about “if and how something works in Polish rather than digging deeper to actually understand" (PL02).

5.3.3. Machine translation

Three participants used the built-in machine translation feature to complete the task – two used it to translate all clips, and one used it to translate four out of five clips. They explained that because they use machine translation in their professional lives, they were "curious" (PL02) to see if it would also be useful in the AD context. Overall, they were pleased with the results; as one participant noted, AD seemed to lend itself particularly well to machine translation because the descriptions are concrete and not abstract, and "machine translation can handle such concrete and precise texts quite well" (PL04). In addition, they believed that machine translation shortened the time required to complete the task because "post-editing took less time than translating from scratch" (PL04).

Having said that, all participants underlined that while in some passages they "did not change anything at all or corrected some minor details" (PL04), others needed far more intervention and double-checking with the source text and image because "at times machine translation would produce something suspicious" (PL05).

All in all, participants were generally positive about machine translation. Still, they emphasised using it primarily "as a tool for inspiration, for support, and not as a workhorse that will translate for them" (PL05).

5.4. Discussion

Participants in the study exhibited a generally positive attitude towards using pivot templates. However, it is worth noting that the participants were not experienced describers but subtitlers, with one exception. This aspect may pose limitations since, as the participants acknowledged, they might not have identified all the potential issues.

Additionally, their lack of experience in audio description could have influenced the quality of the output. This is a crucial consideration as the implementation of this workflow progresses. In the project's next phase, the descriptions generated by the participants will be assessed and compared against descriptions created from scratch to evaluate their overall quality. Nonetheless, the preliminary analysis concerning the impact of using templates on describing culture-specific references indicates that translated audio descriptions encompass a more significant number of culture-specific references and exhibit fewer errors (Jankowska, 2023). This finding highlights the potential benefits of using pivot templates in enhancing the inclusion of cultural nuances within audio description. This is also supported by the opinions of study participants, who underlined that the most prominent feature of templates was the identification and explanation of culture-specific references.

The absence of seasoned describers among the participants provided a unique perspective when evaluating pivot templates, as their assessment was not influenced by the potential impact on their own profession. On the one hand, this could have facilitated a more objective analysis of the templates. However, an essential human aspect was overlooked in this evaluation. Upon analysing the interview data, it became apparent that the participant with significant audio description experience was more hesitant about using templates. While acknowledging their logical benefits, also for the users, they emphasised that it influenced the final script and did not come without challenges. Their attitude reflected an apparent struggle in navigating templates in their work. This sentiment was reinforced by informal discussions with describers who voiced apprehension about potentially losing the creative aspect they highly cherish in their jobs. A recent study on job satisfaction among describers highlighted the importance of creativity, as it emerged as a significant factor valued by describers in their work (Zajdel et al., 2024).

The insights from this participant underscore the complex dynamics involved in adopting pivot templates and highlight the importance of considering the nuanced perspectives of experienced describers in future research and implementation.

6. Conclusions

Introducing (pivot) templates presents advantages and disadvantages, emphasising the necessity for a nuanced approach that carefully weighs this practice's potential benefits and drawbacks. On the one hand, translating audio description allows for expanding access to audiovisual content. However, it is crucial to note that this advantage is contingent upon the production of high-quality audio descriptions within the translation workflow. Without ensuring the delivery of accurate and meaningful audio descriptions, the purported accessibility would be misleading and ineffective.

Introducing (pivot) templates in audio description also raises important considerations regarding the impact on the profession of describers. The overall effect of (pivot) templates on the describer profession largely depends on how they are implemented and utilised. Striking the right balance in incorporating templates is essential, as it should serve as a valuable tool rather than overshadow or replace the skills and insights that audio describers bring to the field.

Therefore, a thoughtful and well-informed approach is essential in navigating the potential advantages and challenges of implementing (pivot) templates. Ultimately, the goal should be to enhance the accessibility of audiovisual content for all audiences while supporting the continued growth and development of audio description professionals.

Acknowledgements

I extend my sincere gratitude to the participants of this study whose invaluable time and openness made this research possible. Your willingness to share your opinions has greatly enriched this work.

I am deeply thankful to Nina Reviers for her invaluable insights into this article and her unwavering support throughout the research process. Her guidance has been instrumental in shaping this work into its final form.

This work was supported by Universiteit Antwerpen: TTZAPBOF Translating and interpreting in the global, digital age.

References

ADLAB PRO. (2019a). Module 2. Unit 6. Culture. UAB Digital Repository of Documents. https://ddd.uab.cat/record/201969

ADLAB PRO. (2019b). Module 2. Unit 6.

Culture.

How to deal with cultural references. UAB Digital Repository of

Documents. https://ddd.uab.cat/record/201969

Allen, W. (Director). (2008). Vicky, Cristina, Barcelona [Film]. Mediapro; Wild Bunch.

Alvarez Ortiz, V. (2019, August 10). Pivot language templates in audiovisual translation: Friends or foes? Audiovisual Division Part of the American Translators Association. https://www.ata-divisions.org/AVD/pivot-language-templates-in-audiovisual-translation-friends-or-foes/

Artegiani, I., & Kapsaskis, D. (2014). Template files: asset or anathema? A qualitative analysis of the subtitles of The Sopranos. Perspectives, 22(3), 419–436. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2013.833642

Braun, S., & Starr, K. (2019). Finding the right words: Investigating machine-generated video description quality using a corpus-based approach. Journal of Audiovisual Translation, 2(2), 11–35. https://doi.org/10.47476/jat.v2i2.103

Braun, S., & Starr, K. (2022). Automating audio description. In C. Taylor & E. Perego (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of audio description (pp. 391–406). Routledge.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Broadcasting Regulatory Policy CRTC 2015-104. Let’s Talk TV. Navigating the Road Ahead – Making informed choices about television providers and improving accessibility to television programming. https://crtc.gc.ca/eng/archive/2015/2015-104.htm#fnb6

Coira, J. (Director). (2010). 18 Comidas [Film]. Tic Tac Producciones; ZircoZine; Lagarto Cine.

Díaz Cintas, J. (2001). Striving for quality in subtitling: The role of a good dialogue list. In Y. Gambier & H. Gottlieb (Eds.), (Multi) Media translation (pp. 199–211). John Benjamins.

Directive 2010/13/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 10 March 2010 on the coordination of certain provisions laid down by law, regulation or administrative action in Member States concerning the provision of audiovisual media services (Audiovisual Media Services Directive, (2010). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2010/13/oj

Directive (EU) 2019/882 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 April 2019 on the accessibility requirements for products and services (Text with EEA relevance), (2019). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32019L0882

Fernández-Torné, A., & Matamala, A. (2016). Machine translation and audio description? Comparing creation, translation and post-editing efforts. Skase. Journal of Translation and Interpretation, 9(1), 64–87. http://www.skase.sk/Volumes/JTI10/pdf_doc/05.pdf

Fernández Torné, A. (2016). Machine translation evaluation through post-editing measures in audio description. InTRAlinea, 18. https://www.intralinea.org/archive/article/machine_translation_evaluation_through_post_editing_measures_in_audio_descr

European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. (2014). Are there legal accessibility standards for public and private audiovisual media? https://fra.europa.eu/en/content/are-there-legal-accessibility-standards-public-and-private-audiovisual-media

Georgakopoulou, P. (2006). Subtitling and globalisation. The Journal of Specialised Translation, 6, 115–120.

Georgakopoulou, P. (2009). Developing audio description in Greece. MultiLingual, 20(8) 38–42. https://multilingual.com/pdf-issues/2009-12.pdf

Georgakopoulou, P. (2019). Template files: The Holy Grail of subtitling. Journal of Audiovisual Translation, 2(2), 137–160. https://doi.org/10.47476/jat.v2i2.84

Herrador Molina, D. (2006). La traducción de guiones de audiodescripción del inglés al español: Una investigación empírica [The translation of audio description scripts from English to Spanish: An empirical investigation] [Unpublished MA thesis]. Universidad de Granada.

Hyks, V. (2005). Audio description and translation. Two related but different skills. Translating Today, 4, 6–8.

Jankowska, A. (2015). Translating audio description scripts. Translation as a new strategy of creating audio description. Peter Lang. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.3726/978-3-653-04534-5

Jankowska, A. (2021). Audio describing films: A first look into the description process. The Journal of Specialised Translation, (36, 26–52.

Jankowska, A. (2023). Using annotated pivot templates to transfer culture specific references in audio description: Translators’ performance, strategies, and attitudes. Perspectives, 1–17..

https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2023.2281972

Jankowska, A., Milc, M., & Fryer, L. (2017). Translating audio description scripts… into English. Skase. Journal of Translation and Interpretation, 10, 2–16. http://www.skase.sk/Volumes/JTI13/pdf_doc/01.pdf

Kapsaskis, D. (2011). Professional identity and training of translators in the context of globalisation: The example of subtitling. The Journal of Specialised Translation, 16, 162–184.

López Vera, J. F. (2006). Translating audio description scripts: The way forward? Tentative first stage project results. In M. Carroll, H. Gerzymisch-Arbogast & S. Nauert (Eds.), Audiovisual Translation Scenarios: Proceedings of the Marie Curie Euroconferences MuTra: Audiovisual Translation Scenarios. https://www.euroconferences.info/proceedings/2006_Proceedings/2006_Lopez_Vera_Juan_Francisco.pdf

Martínez-Lázaro, E. (Director). (2015). Ocho apellidos catalanes [Film]. LaZona Films; Kowalski Films; Telecinco Cinema.

Matamala, A. (2006). La accesibilidad en los medios: Aspectos lingüísticos y retos de formación [Accessibility in the media: Linguistic aspects and training challenges]. In R. Pérez-Amat García & Á. Pérez-Ugena y Coromina (Eds.), Sociedad, integración y televisión en España [Society, integration and television in Spain] (pp. 293–306). Laberinto. https://ddd.uab.cat/pub/caplli/2006/170070/matamala_2006.pdf

Mazur, I. (2020). Audio description: Concepts, theories and research approaches. In Ł. Bogucki & M. Deckert (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of audiovisual translation and media accessibility (pp. 227–248). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-42105-2_28

United Nations. (2006). Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Treaty Series, 2515, 3.

Netflix. (2021a). Audio Description Style Guide v2.3 Netflix.

Netflix. (2021b). Timed Text Style Guide: Subtitle Templates. https://partnerhelp.netflixstudios.com/hc/en-us/articles/219375728-Timed-Text-Style-Guide-Subtitle-Templates

Nikolić, K. (2015). The pros and cons of using templates in subtitling. In R. Baños Piñero & J. Díaz Cintas (Eds.), Audiovisual translation in a global context. Mapping and ever-changing landscape (pp. 112–117). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137552891

Oncins, E. (2022). Audio description translation. In C. Taylor & E. Perego (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of audio description (pp. 447–459). Routledge.

Orero, P. (2007). ¿Quién hará la audiodescripción comercial en España? El futuro perfil del descriptor [Who will make the commercial audio description in Spain? The future profile of the describer]. In C. Jiménez Hurtado (Ed.), Traducción y accesibilidad: Subtitulación para sordos y audiodescripción para ciegos: nuevas modalidades de traducción audiovisual [Translation and accessibility: Subtitling for the deaf and audio description for the blind: new modalities of audiovisual translation ] (pp. 111–120). Peter Lang.

Oristrell, J. (Director). (2009). Dieta mediterránea [Film].

Oziemblewska, M., & Szarkowska, A. (2022). The quality of templates in subtitling. A survey on current market practices and changing subtitler competences. Perspectives, 30(3), 432–453. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2020.1791919

Plaza, M. (2017). Cost-effectiveness of audio description production process: comparative analysis of outsourcing and ‘in-house’ methods. International Journal of Production Research, 55(12), 3480–3496. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2017.1282182

Remael, A., & Vercauteren, G. (2010). The translation of recorded audio description from English into Dutch. Perspectives, 18(3), 155–171. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2010.485684

Romero Fresco, P. (2013). Accessible filmmaking: Joining the dots between audiovisual translation, accessibility and filmmaking. The Journal of Specialised Translation, 20, 201–223.

Romero Fresco, P. (2019). Accessible filmmaking. Integrating translation and accessibility into the filmmaking process. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429053771

Sade, Y., Garg, A., & Plaza, M. (2011). Business process model for incorporating descriptive audio in TV show production. In J-L. Ferrier, A. Bernard, O. Y.Gusikhin & K. Madani (Eds.), Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Informatics in Control, Automation and Robotics (pp. 399–406). SciTePress. https://www.scitepress.org/PublishedPapers/2011/35317/35317.pdf

Starr, K. (2022). Audio description for the non-blind. In J. R. Taylor & E. Perego (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of audio description (pp. 476–494). Routledge.

Starr, K. L., Braun, S., & Delfani, J. (2020). Taking a cue from the human: Linguistic and visual prompts for the automatic sequencing of multimodal narrative. Journal of Audiovisual Translation, 3(2), 140–169. https://doi.org/10.47476/jat.v3i2.2020.138

Twenty-First Century Communications and Video Accessibility Act of 2010, Pub. L. No. 111–260, 124 Stat. 2751 (2010). https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PLAW-111publ260/pdf/PLAW-111publ260.pdf

Szarkowska, A. (2011). Text-to-speech audio description: Towards wider availability of AD. The Journal of Specialised Translation, 15, 142–163.

Taylor, C., & Perego, E. (Eds.). (2022). The Routledge handbook of audio description. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003003052

The Audiovisual Media Services Regulations 2014, No. 2916 (2014) https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2014/2916/pdfs/uksi_20142916_en.pdf

Zajdel, A., Schrijver, I. & Jankowska, A. (2024). What goes on behind the scenes? Exploring status perceptions, working conditions and job satisfaction of audio describers. Perspectives, 1–17.. https;//doi.org10.1080/0907676X.2023.2297245

Data availability statement:

The data generated and analysed during this study are not publicly available due to the participants' lack of written consent for public data sharing. Given the personal nature of this research and the potential identifiability of participants based on their utterances, supporting data cannot be made available. However, inquiries regarding specific aspects of the study can be directed to the corresponding author for further information and clarification.

Disclaimer

The authors are responsible for obtaining permission to use any copyrighted material contained in their article and/or verify whether they may claim fair use.

Appendix 1

Part 1

How would you evaluate the complexity of this task?

How do you perceive working with a template and translating audio descriptions?

What are the strengths and weaknesses of employing templates in audio description?

What factors contribute to a smoother template workflow, and what challenges do you encounter?

If given the chance, would you make any modifications to this workflow?

If you were creating audio descriptions from scratch, would there be differences, and if so, in what ways would they manifest in comparison to the translated version?

In what ways, if any, did you find the annotations helpful?

How could the annotations be enhanced for greater effectiveness?

What led you to choose machine translation, and what were your impressions of its utility in this context?

Part 2

How did you approach the translation of cultural references?

What influenced your choice of strategies?

ORCID 0000-0001-6863-5940; e-mail: anna.jankowska@uantwerpen.be↩︎

Notes

https://www.videotovoice.com/↩︎

The exact values of the reading speeds are not available.↩︎

Language Service Providers (LSPs) use two types of templates. The unlocked template permits the translators to modify the time codes, segmentation and content (e.g., to add/delete subtitles; shorten/extend the duration time and content). The locked template does not allow any changes to be made.↩︎

The interview protocol is available in Appendix 1↩︎

All interviews were conducted in Polish, and the quotations featured in this paper were translated into English by the author.↩︎

The participant was referring to a prior discussion about the fact that when describing a film from their own culture describers may not include elements that are obvious for that culture but not for others. For example, in the previous experiment, while describing Spanish clips, Polish describers more often than Spanish describers referred to sunny weather.↩︎