An Experimental Study on Viewing Perception and Gratification of Danmu Subtitled Online Video Streaming

Sijing

Lu1, University of Warwick

Xijinyan Chen2, Wake

Forest University

ABSTRACT

With the surge of participatory culture and dynamic of media convergence, danmu have experienced their continued proliferation on East Asian online streaming. Facilitated by pseudo-synchronicity and congruency technologies, existing research has focused on describing and conceptualising the final product of danmu rather than being grounded in the empirical process of receiving danmu. We know little of how audiences perceive danmu and to what extent danmu affect viewers’ gratifications. Adopting an online-based experiment, this study contributes to examining viewers’ engagement with and gratifications from different types of danmu. It attempts to understand what types of danmu matter to the audience’s viewing gratifications in terms of its content and multimodality, and what (dis)connections can be observed between the audience reception of danmu and conventional subtitles. The results show that extra cultural information danmu stand out as the most gratifying type, significantly satisfying viewers’ utilitarian and hedonic needs for information and entertainment seeking. Scrolling speed and size are the two most influential multimodal factors in viewers’ gratifications with danmu. However, the potential connections between conventional subtitles and danmu depend highly on a video's content or genre.

KEYWORDS

danmu, subtitling, online streaming, audiovisual translation, uses and gratifications, audience reception.

1. Introduction

In 2006, nicovideo.jp, the biggest video-streaming platform in Japan, introduced a new feature that user comments can be directly overlaid onto the video screen and synchronised with the playtime point (Chen et al, 2015). Facilitated by pseudo-synchronicity and congruency technologies (Johnson, 2013; Yang et al., 2021), this practice allows users to post and read live comments onto the video while watching. The resultant comments resemble a ‘bullet curtain’ effect known as ‘danmaku’ in Japanese or ‘danmu’ in Chinese. Pseudo-synchronicity enables users to experience a sense of simultaneous interaction, and congruency refers to the phenomenon where the alignment between danmu and the recommended content is notably strong during specific moments in a video. According to Hamasaki et al. (2009, p. 222–223), danmu are defined as live comments that are synchronised into “a specific playback time at a specific position in the video, which gives people a sense of sharing the viewing experience virtually”. The pop-up sending technology accessible on the video playback page allows audiences to contribute their own remarks and create an animated comment-track, and this has created a wall of ‘flowing text’ that is quickly shown on the video screen and captures the audience’s ‘fleeting’ and ‘live’ experience of online streaming. It is noteworthy that danmu acts as a form of live comments that significantly enhances the social act of communication, yet it may not be necessarily related to translational practices. Given the focus of this study on the reception of foreign language videos, it is anticipated that discussions pertaining to translation will be prevalent within danmu.

In the past decade, danmu subtitled videos3 have transitioned from a “niche entertainment” to a standard component of the majority of video streaming sites in China (Zhang and Cassany, 2020). As stated in the Alexa traffic ranks (Chen et al., 2017), Bilibili, the largest danmu-sharing video streaming platform, was the fourth most popular online video service in China. Beyond that, many other social networking platforms, including e-commerce and product recommendation community Xiaohongshu and game-focused live streaming site Douyu, began to follow the trend and support a danmu interface in the past years. Given such rapid proliferation and increased exposure, danmu began to be valued by scholars from media, communication, education, and translation domains in terms of their semiotic visualisation and interface affect (Li, 2017; Yang, 2021), their participation in promoting intercultural understanding and language learning (Zhang and Cassany, 2019; Zhang and Cassany, 2020), their capability in enhancing course engagement in online instruction (Lin et al., 2018), and their capacity to construct an online discussion space of plural voices (Ma and Ge, 2014; Zhu, 2017).

Yet the existing research focuses on describing and conceptualising the final product of danmu rather than the empirical process of receiving danmu. Our understanding of how audiences perceive danmu and the extent to which danmu influence their viewing gratification remains limited. It is plausible that audiences watching danmu videos have distinct needs compared to those who watch videos on television or DVD. This article contributes to examining audience’s engagement with and gratifications of different types of danmu. Specifically, it sets out to address the following two research questions: (1) Which types (in terms of its content and multimodality) of danmu most matter to audience’s viewing gratifications? (2) What (dis)connections can be observed between the audience reception of danmu and conventional subtitles?4 The data was collected from an online-based experiment that 104 native Chinese audiences were informed to watch a five-minute English video on Bilibili with the presence of different types of danmu, then followed by answering a self-reported survey with gratification ratings. This article aims to revisit the essence and rationale behind the widespread popularity of these user-generated and technology-enabled practice on Chinese online video-streaming platforms. It seeks to explore this informal participatory phenomenon from the perspective of the audience and open up new methodological directions by empirically examining its potential impacts on non-professional audiovisual translation and the broader creative industries.

2. Characterising Danmu on Online Streaming

As attested by a growing body of literature, danmu have been widely held to foster the evolution of congruency technologies and media capabilities. As Liu et al. (2016) outline, the danmu system encompasses all five characteristics in terms of transmission and processing capabilities as proposed in Dennis et al.’s (2008) media synchronicity theory. The five characteristics include transmission velocity (the speed of delivering comments to users), parallelism (the degree to which users can receive numerous comments concurrently), symbol sets (the various methods by which a medium permits the encoding of information for communication), rehearsability (how the medium allows the sender to rehearse or refine a comment), and reprocessability (how the medium allows a comment to be reconsidered or reprocessed). These capabilities enable danmu to merge the symbol sets of video, audio, and text into a single channel. Comparing Japanese Nico Nico Douga and Chinese Bilibili, danmu seem to emphasise “playfulness” and a sense of “private intimacy” (Nakajima, 2019, p. 99). They move away from the “rationality” assumption of the existing public sphere framework, as well as blur the boundary between public and private due to their unique quality of pseudo-synchronicity. Johnson (2013, p. 301) notes that this form of live commenting creates a “feeling of time”, in which the comments in the feed are arranged based on the time when they were input by the user, rather than the order of input.

Together with an abundance of mistypes in some forms of Japanese language in danmu, Johnson (2013) also notes that the sense of movement and time steers users towards a particular type of vision that, when viewed in conjunction with the counter-transparent communication strategies adopted by its user base, such as orthographic mistakes, is a component of a shift between denotational and pictorial forms of text production that blurs the line between reading and other forms of vision. The ‘liveliness’ or ‘sense of time’ characteristic of danmu has also been examined by scholars such as Ouyang and Zhao (2016) and Yang (2021), who discuss how the “illusion of communication” is created by the temporary and mostly unidirectional nature of danmu communication. They note that such a temporary aspect is particularly important because a comment is displayed at the exact moment it was entered in the video, it can be directed at a specific scene, effectively synchronising comments with the video’s scenes through a built-in timer.

Apart from the discussions on danmu’s implications on synchronisation and co-occurrence media technologies, danmu also highlights viewer’s participation and interactive sociality, facilitating a “multiplicity of possible voices” (Johnson, 2013). It converts the act of watching videos into a social experience by fostering interaction among viewers through the comments feed. As noted by Chen et al. (2013), the importance placed on social connections of danmu is supported by the common phrase “I just came here to read danmu” [我是来看弹幕的]. With a perspective from digital economy, Cao (2021, p. 29) also explains how social network platforms combine subversive text with streaming using a format known as ‘bullet screen’, and how such bullet format “collapses social inequality into a spectacle of money flowing and vanishing on screen”. As noted by Cao (2021), viewers engage with YY.com through sending danmu for free, but hosts often encourage them to purchase and send virtual gifts. This gifting not only allows viewers to exert control over hosts but also grants them a sense of control they may lack in daily life. Cao (2021, p. 41) regards this as a way that the spectacle of social inequality becomes entertainment itself through bullet texting, sustaining the business of online streaming and embodying Debord’s (2014, p. 49) notion that "spectacle is the flip side of money”. He argues that the act of viewing and commenting on content (i.e. sending danmu) not only represents the new business models of tech companies, but also reflects being immersed in a culture of seemingly trivial content that still holds meaning, both in terms of language and economic value. Viewers’ video-watching experience, thus, may be altered, shifting from a solitary experience to an engaged and socially active one (Liu, et al., 2016), subverting the hierarchies of content and comments in a highly visible manner (Xu, 2016), and creating a “virtual heterotopia” where various tactics are employed to challenge and oppose domination, social norms as well as consumerism (Chen, 2021).

3. Uses and Gratifications in Danmu Subtitled Videos

As reviewed previously, danmu subtitled videos can be considered as a form of digital media interwoven with text-based interface and social participation, encompassing both “the motives of consuming TV/videos” and “the motives of utilising internet-based media” (Chen et al., 2017, p. 733). To understand the audience’s reception and gratifications towards danmu commented videos, uses and gratifications theory is used in this study to help identify the potential methodological measures for the experiment. The theory presupposes that viewers intentionally select media on purpose in order to fulfil particular needs and goals, and such behaviour is influenced by viewers' social and psychological dispositions. As Lucas and Sherry (2004, p. 502) note, uses and gratifications theory stands in contrast to the “mechanistic effects model” of media that assumes a direct and one-sided influence of media on message recipients. Instead, uses and gratifications theory is an audience-centred approach, considering each medium or message as just one possible source of influence among many, recognising that audiences are not passive but rather have varying levels of agency and can make active choices in mediated communication (Rubin, 2009). Early in 1970s, gratifications were conceptualised as “need satisfactions”, meaning that individuals obtain satisfaction when their needs are fulfilled by particular types of media sources that align with their expectations (Katz et al., 1974). In line with this assumption, researchers later on uses and gratifications have focused on social and psychological factors as determinants of motivation for using specific media types including reality TV, online newspaper, Twitter, YouTube and TikTok (Yoo, 2011; Chen, 2011; Khan, 2017; Buf & Ștefăniță, 2020; Bossen & Kottasz, 2020), and motives are often modelled as latent constructs that reflect the sought-after gratifications that individuals may potentially obtain through media use. However, it is worth noting that uses and gratifications theory also received criticisms (Elliot, 1974) regarding its individualistic orientation and its lack of attention to media content.

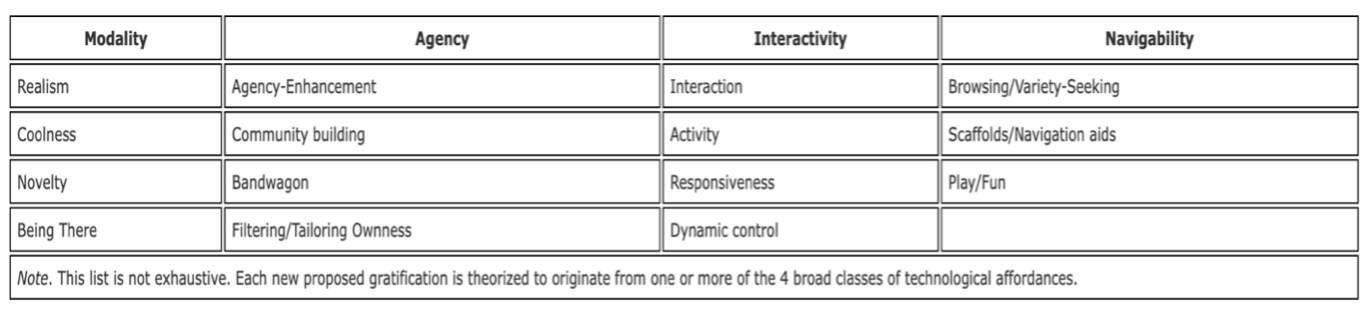

Table 1. Possible New Gratifications from Media Technology (adopted from Sundar and Limperos 2013)

Over the decades, researchers on uses and gratifications theory have identified several typologies of gratifications to understand media use. For instance, Rubin (2009) distinguishes two general types of gratifications, namely content gratifications (obtained from media content) and process gratifications (acquired from the use of media). Stafford et. al (2004) then add a third new form of gratification, centred on the use of media as a social setting on the Internet. Newer media have manifested new capabilities with more specific technologically-enabled gratifications beyond social-psychological origins of needs. Based on Sundar’s (2008) MAIN model (i.e. modality, agency, interactivity, navigability), Sundar and Limperos (2013) illustrate a few examples of new media gratifications derived by users when they engage with the advanced technological affordances (see Table 1):However, as different media serve different needs, this MAIN model seems not to provide a specific account of which social-psychological needs may lead to patterns of use of danmu subtitled videos. While it is assumed that overlap in gratification typologies is very common between old and new media, and that some unique medium-specific gratifications obtained from new media have been associated with traditional media, they are sometimes labelled differently. We then searched typologies of gratifications on danmu subtitled video. To be the best of our knowledge, the only two completed studies that specifically related to uses and gratifications theory satisfactions and needs in watching danmu subtitled videos were conducted by Chen et al. (2015 and 2017). In their 2015 study, danmu are theorised as a form of user-generated media with substantial volunteer effort, and three danmu-related motivations are summarised: information-seeking, social interaction, and self-expression/self-actualisation. In a follow-up study in 2017, Chen et al. argue that four possible needs that might be relevant to danmu subtitled videos gratifications: utilitarian needs, hedonic needs, social needs and self-expression needs. Some of these needs seem to have similarities with MAIN model. For example, social needs align with interactivity-based gratifications that permit users to make real-time interactions with the content in the medium or other viewers. Self-expression and hedonic needs reflect agency-based gratifications that have been significantly transformed by the prevalence of user-generated content, giving more important rise to the voices of users and enabling new enjoyment interface tools such as customisation. Utilitarian needs then partially correspond with navigation-based gratifications that cater to users’ movement in the space to acquire a diverse variety of information.

Now, triangulating the traditional emphasis on social-psychological needs with technology-driven needs, and taking into account the MAIN model and Chen et al.’s studies (2015, 2017) on satisfactions and needs in watching danmu subtitled videos, we found the following four types of gratifications that could be most pertinent to the characteristics of danmu:

Utilitarian needs (U) – information seeking, new knowledge acquisition;

Hedonic needs (H) – entertainment, play/fun, relaxation, passing time;

Social interactivity needs (S) – responsiveness, avoidance of loneliness, self-expression, sense of belonging;

Peer pressure needs (P) – keeping up with the latest trends, bandwagon effect.

After identifying the four potential gratifications relating to danmu subtitled videos, the next step is to design survey measures that not only “tap into emergent uses and gratifications” (Sundar and Limperos, 2013, p. 522), but also deconstruct and describe them in ways that allow us to discern the gratifications gained from media affordances in different types of danmu. To do so, we then conducted a focus group with 6 loyal Bilibili users to create methodological experiment measures that match the aforementioned broad typology in the survey (see 4.2.2).

4. Methodology

4.1 Experiment design

This study involved an online experiment that required participants to watch a five-minute English video clip on Bilibili, and then immediately complete a self-reported survey with a few questions regarding their degree of gratifications on different types of danmu. The experiment received full ethical approval from Wake Forest University (IRB 00024770). A total of 104 participants (32 males, 65 females, and 7 prefer not to say) were recruited from Chinese native speakers who are students based in the UK and USA’s universities. As the purpose of the study is to examine how different types of danmu are received and influence audience’s gratifications, participants who do not have a watching habit with danmu were excluded. We made it clear in our recruitment advertisement that this experiment would only be available to those with prior experience or a habit of viewing danmu subtitled videos. Participants were not informed what genres of videos they would watch prior to the experiment. They were, however, only informed that they would be watching a short English video with bilingual subtitles and then answer an online survey. This contributes to constructing a more natural experimental setting and avoids having the participants pay special attention to danmu. We had in fact thought about recruiting participants to come to an offline laboratory room where a researcher would provide them with the selected video on a pre-prepared computer and then hand out the survey. We concluded, however, that this would disrupt the authentic scenario of people watching online videos alone at home and thus influence the ecological validity of the experiment. An online experiment is believed to enhance a more real-life setting and obtain more reliable and trustworthy data in this situation.

4.2 Materials

4.2.1 The Video Clip and Typology of Danmu

A five-minute video named How Does the British Royal Family Prepare for a Wedding? (Youzimu, 2018) was chosen as the experiment material in this study based on the following criteria:

Distribution platform: this video was streamed on Bilibili, one of the largest video streaming sites with a strong emphasis on user-generated content and user participation in the form of overlaid danmu. In order to ensure the consistency of participant’s understanding towards danmu, we asked participants to refer to the latest danmu interface setting window down below the video on Bilibili (as shown in Figure 1). As the interface setting shows, danmu can be divided into regular and advanced, where regular danmu includes the user's ability to set the size, colour, scrolling speed, transparency and displaying some common personalised danmu features, and advanced danmu have more special effects and can only be used by advanced Bilibili members [高级会员] or uploaders [up主]. There is also a ‘blocking function’ in the setting window, which not only allows viewers to block certain ‘keywords’, but also has a more advanced filtering function to allow viewers to add, synchronise and delete blocked content in the ‘blocking list’ [屏蔽列表]. Such function can effectively deactivate malicious comments and taboo phrases.

Figure 1. Screenshot of danmu interface setting window (Youzimu, 2018)

When different semiotic modes are used to create meaning, this is referred to as multimodality (Kress and Van Leeuwen, 2001). For the purpose of this study, four main semiotic modes were connected with danmu’s multimodality, i.e. colour, size, transparency and scrolling speed. It is assumed that the dynamic layout of these modes may make a different impact on audience’s watching experience, thus causing different degrees of gratifications. In order to ensure participants’ consistency in receiving danmu, we required all participants to refer to regular danmu and not to use the blocking function during the experiment, so as to ensure that they were presented with sufficient different types of danmu. The bilingual subtitles in the video clip were created by Youzimu, one of the largest fansubbing communities who translate English videos into Chinese on Bilibili with over 3.6 million subscribers. Such massive popularity of Youzimu demonstrates the success of their translation and the wider acceptance of their works.

Readability of bilingual subtitles: it is believed that if the bilingual subtitles are too difficult to read, it would distract audience’s watching experience and thus influence the reception process of other displaying elements such as danmu. We thus measured the readability of bilingual subtitles in the selected video. For Chinese subtitles, we used the Chinese Readability Index Explorer, CRIE (Sung et al., 2016), to measure the text complexity of the translation; for English subtitles, we used Flesch-Kincaid Reading Ease to measure the level of the original transcript. According to CRIE, characters with 1-10 strokes are deemed as easy, and characters with over 21 strokes are difficult. Table 2 shows that 87.1% of characters are low-difficulty characters and only 1 character is a difficult word, indicating that the Chinese translations are quite easy to read. For English subtitles, the score is 62.7, which aligns with a school level of 8th-9th grade and also indicates that the text should be easily comprehended.

| Chinese subtitles | Number of sentences | Number of characters | Difficult characters | Low-stroke characters | Low-stroke character % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50 | 1475 | 1 | 1286 | 87.1% | |

| English subtitles | Number of sentences | Number of words | Average words per sentence | Average syllables per word | Flesch-Kincaid Ease score |

| 50 | 850 | 17 | 1.5 | 62.7 |

Table 2. Readability of bilingual subtitles

Typology and frequency of danmu: as for the typology of danmu, we did not presuppose any top-down framework to categorise them. Instead, we used a manually recursive and inductive process as follows. First, we randomly selected four videos (Youzimu, 2019; Youzimu, 2022a; Youzimu, 2022b; Youzimu, 2022c) that belong to different genres (i.e. science, music MV, life vlogs and news) on Youzimu. Then we exported all the 544 danmu from the four videos into a Word file and grouped similar danmu and drafted an initial typology (4 categories). After that, we asked a third person, who is an experienced content creator on Bilibili, to review the initial categories we created and discussed necessary changes by expanding four categories into five (Table 3) to better diversify the forms of danmu. Since the last category ‘others’ contains only 5 cases in the selected video and its content is not concrete, this category will not be discussed in this study.

| Typology | Examples |

|---|---|

Tucao danmu (i.e. a type of humourous language that playfully uncovers the truth in a sarcastic and laughable tone) |

吃不起的狗粮 (can’t afford this dog food) emm好像伏地魔 (emm, seems like Voldemort) 不知道的人以为在看猴子(people who don't know might think they're watching monkeys) |

Short commentary danmu (i.e. a commentary on a phenomenon, plot or character) |

黛安娜真美 (Diana is so beautiful) 哇这三张图选的太具代表性了(wow, these three pictures are so representative) |

Extra cultural information danmu (i.e. a piece of complementary information that is not provided in the original video) |

有一首古典音乐也叫威风凛凛 (There is a classical music piece also called Pomp and Circumstance) 婚礼早餐通常不是吃早饭 就是婚宴的意思 (Wedding breakfast usually refers to a reception or a meal served after the wedding) |

Translation-related danmu (i.e. a translation on the original dialogue or to provide alternative solution to the existing translation) |

The Lord Chamberlian翻译成“宫务大臣”比较好 (It’s better to translate “The Lord Chamberlian” as “宫务大臣”) groom这里应该是新郎 (groom means “新郎” here) |

Others (i.e. symbols, letters, punctuations) |

2333 ????? Hhhhhhhh |

Table 3. Typology of danmu in terms of content

Additionally, the number of danmu is not always balanced. Some videos have too many danmu, causing the screen to be fully covered; while some may contain very few danmu, which do not provide enough data for this study. Therefore, the video we selected was considered 'neutral' with neither excessive nor insufficient danmu. Table 4 below presents the general information of the video:

| Title | Duration | Number of danmu |

Danmu frequency | Frequency of different forms of danmu |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| How Does British Royal Family Prepare for a Wedding | 5:25 | 105 | 1 danmu/2.95s | Tucao danmu (35) Short commentary danmu (42) Extra cultural information danmu (14) Translation danmu (9) Others (5) |

Table 4. Information of the selected video

4.2.2 Survey Design

The survey was conducted in Chinese on Wenjuanxing, a professional Chinese online questionnaire platform with multi-functional services including evaluation, voting, custom reports and results analysis. The survey was divided into four parts: (1) demographic information; (2) gratifications for danmu with different content; (3) gratifications for danmu with different modalities; (4) (dis)connections between danmu and conventional subtitles. In order to accurately identify measuring items that correspond to the four gratifications as reviewed in section 3, we did a focus group with 6 Bilibili loyal users who are experienced in watching danmu subtitled videos. Focus group was used due to its advantages in encouraging danmu viewers to reflect upon personally relevant and authentic experiences. All of the focus group participants were deemed frequent danmu viewers (i.e. watching danmu subtitled videos every day), with watching experience ranging from 3 to 5 years. We asked focus group participants the needs to watch each type of danmu, and then sorted out their responses and identified 14 methodological measuring items that correspond to each type of danmu. These 14 measuring items were used as the basis for identifying the participants’ degree of gratifications towards different types of danmu (see Table 6).

In Part 2 of the survey, there was one open-ended question about which types of danmu influence participant’s watching gratifications most and why, and then, participant’s gratifications towards different content of danmu was measured by rating a seven-point 14-item Likert scale. Participants indicate their agreement with the scale items by clicking from seven responses (i.e. strongly disagree, disagree, disagree somewhat, neutral, agree somewhat, agree, strongly agree). The reason to use a seven-point Likert scale is that it captures the best sentiment and cognitive load of the participants, providing better accuracy of subject evaluation and delivering more data points to run statistical results (Finstad, 2010). Part 3 measured participant’s gratifications towards different modalities of danmu, including size, colour, scrolling speed and transparency. It includes 4 Likert scale questions and 4 multiple choice questions. Likert scale aimed to ask the degree of size/colour/scrolling speed/transparency’s impact on participants’ watching gratifications; multiple choices asked participants to use interface window to self-adjust the setting and then choose the most favourite mode (e.g. what is your favourite danmu scrolling speed?). Part 4 included three questions, with one open-ended question to ask participants when they would frequently read danmu, and 2 Likert scale questions to ask participants’ attitudes towards the potential connections between danmu and conventional subtitles.

4.3 Data Analysis

Among 104 participants, 79.8% participants are deemed as frequent danmu watchers (above 3-5 times per week), 8.6% moderate danmu watchers (1-3 times per week), and 1.9% mild danmu watchers (less than once per week). To measure the strength of gratifications, data from the seven-point Likert scales were subsequently converted into values of increasing gratification, ranging from 1 (i.e. strongly disagree of gratification) to 7 (i.e. strongly agree of gratification), and average scores were calculated for each measuring item. The internal reliability and consistency of 14 measuring items were measured by using Cronbach Alpha, obtaining acceptable to excellent coefficients (Table 5). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were respectively 0.864, 0.881, 0.921 and 0.896, all indicating a very high reliability and confirming that the measuring items were well-developed. To analyse the data of multiple choices, Wenjuanxing’s built-in analysis tool was used to generate statistical figures. As for the two open-ended questions, we used Wenjuanxing’s text frequency analyser to identify the most commonly used terms in responses, and then manually identify broad categories of responses.

| Tucao danmu | Short commentary danmu | Extra cultural information danmu |

Translation danmu |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cronbach Alpha | 0.864 | 0.881 | 0.921 | 0.896 |

Table 5. Reliability of 14 measuring items by using Cronbach Alpha

5. Findings and Discussions

5.1 Gratifications from danmu with different content

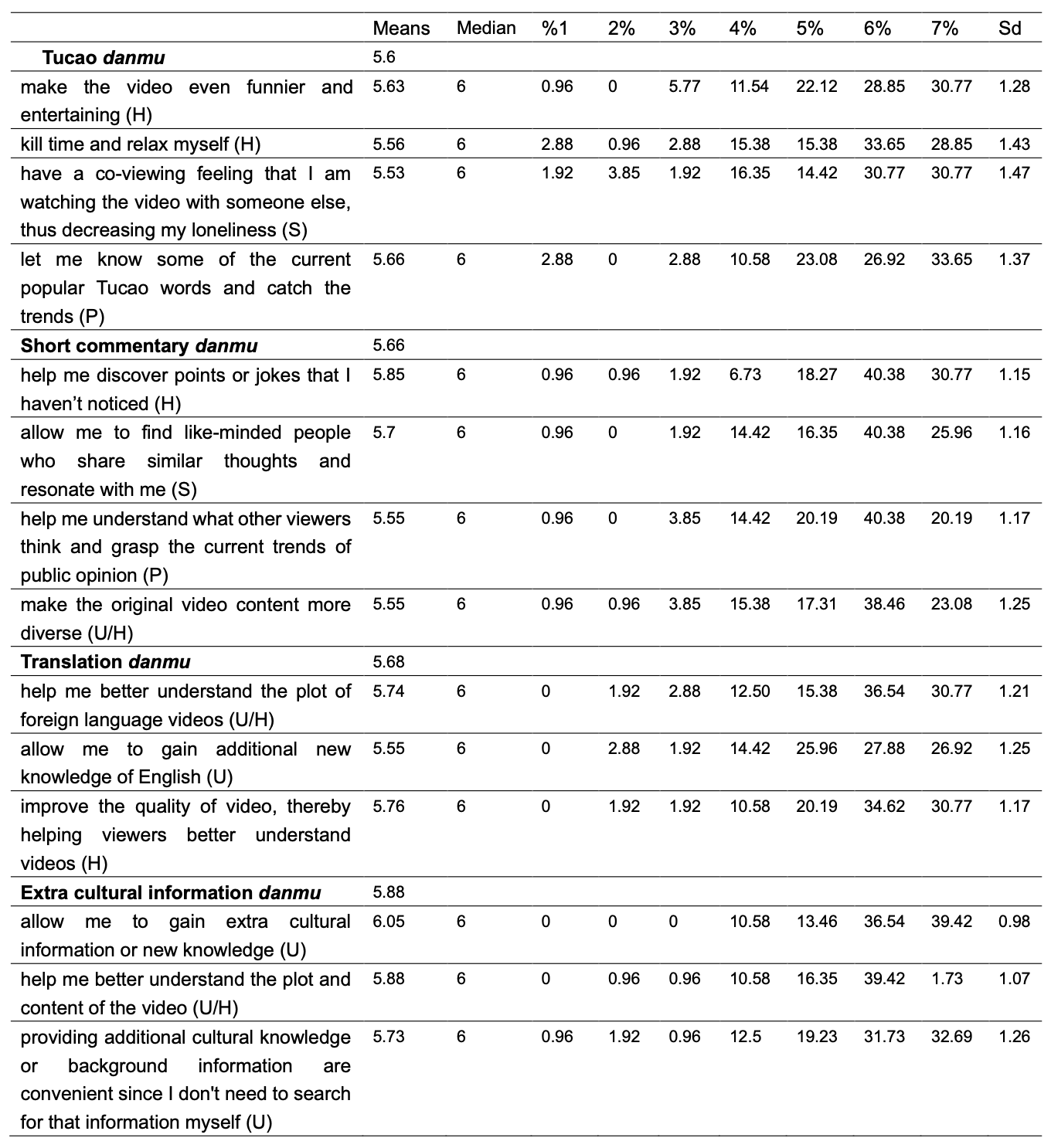

Table 6 shows the results of participants’ degree of gratifications from danmu with different content. 1-7 stand for increasing degrees of gratification, with 1 corresponding to the lowest degree and 7 to the highest degree. By comparing the mean ratings across different types, we could notice there are some differences in how they are perceived by the participants. Overall, tucao danmu has an average mean rating of 5.6, which is slightly lower than the rating of 5.66 for short commentary danmu. Translation danmu has an average mean rating of 5.68, which is slightly higher than the ratings for both tucao and short commentary danmu. Extra cultural information danmu has the highest average mean rating of 5.88 among all the types. Such results show that participants' degree of gratification varies across different types, though not dramatically. Extra cultural information danmu, however, stands out as the most gratifying type and has the highest impact on viewers' gratification. If we look into the ratings of 14 specific measuring items, we can find that the top two highest mean ratings are also in the category of extra cultural information danmu, which is 6.05 for “allow me to gain extra cultural information or new knowledge (U)” and 5.88 for “help me better understand the plot and content of the video (U/H)”. The third highest mean is “help me discover points or jokes that I haven’t noticed (H)” with a rating of 5.85.

Table 6. Survey results of gratifications towards danmu with different content

Combining the uses and gratifications theory reviewed in section 3, the highest top three ratings appear to satisfy people’s utilitarian and hedonic needs, linking closely to a kind of information and entertainment seeking. Previous studies on uses and gratifications theory have also highlighted information seeking as a prevalent motive for media usage, alongside entertainment (McQuail, 2000). In Khan’s (2017) study about viewers’ gratifications from YouTube videos, they similarly concluded that information seeking is a crucial motive alongside with entertainment purpose from a user’s perspective. Viewers may not only seek information through viewing the content of the video itself, but also through reading YouTube comments. This resonates with danmu’s characteristics, synchronously displaying live comments that may offer valuable information to viewers in the most informal setting. The importance of information-seeking can also be proved in participants’ responses to the open-ended question “what types of danmu do you think that most influence your gratifications? Why?”. According to the text frequency analyser, we find the top three categories of keywords (Table 7). The frequency of keywords in information seeking such as “content”, “information”, “culture” and “knowledge” echoes the findings in Likert scale, all indicating that the acquisition of new information is the most important reason why danmu can bring the greatest pleasure to the viewers.

| keywords | frequency | |

|---|---|---|

Information Seeking (45) |

content 内容 | 15 |

| information信息 | 12 | |

| short comment短评 | 6 | |

| culture文化 | 4 | |

| value价值/有用 | 3 | |

| knowledge知识 | 3 | |

| nutrition营养 | 2 | |

Entertainment (36) |

tucao吐槽 | 12 |

| fun有趣 | 10 | |

| humorous幽默 | 6 | |

| jokes梗 | 6 | |

| happy快乐/欢乐 | 3 | |

| Sociality (15) | resonation共鸣 | 5 |

| together一起 | 5 | |

| interaction互动 | 3 | |

| loneliness孤独/寂寞 | 2 |

Table 7. Frequency of keywords to the open-ended question “what types of danmu do you think

that most influence your gratifications? Why?”

Amongst other types, short commentary (5.66), translation (5.68) and tucao danmu (5.6) do not show significant differences in degree of gratifications from participants. If we look into the specific items from these three types, apart from utilitarian and hedonic needs, the rating for social interactivity needs “allow me to find like-minded people who share similar thoughts and resonate with me (5.7)” and peer pressure needs “let me know some of the current popular tucao words and catch the trends (5.66)” also ranked a bit higher among other items. As Yang et al. (2021, p. 1195) indicate, danmu allows individuals to “fulfill their inner needs for warmth, closeness and connection” in virtual worlds, which boosts their propensity to psychologically engage with others and foster an immersive experience of social presence. The sense of resonance normally occurs when viewers send danmu with similar messages about a particular point, generating a live sense of collective identification and thereby bringing synchronic pleasure and satisfaction to the viewers. For example, in surveys, many participants mentioned that when a video reaches its climax, the viewers’ emotional experiences are maximised by seeing similar comments flying across the screen and feeling that many others are getting excited together with themselves and thus gaining a sense of “not being alone anymore”. Compared with traditional comments, danmu exhibit a more “microscopic” attribute (Li and Wang, 2015) due to their congruency nature. They prompt viewers to provide feedback pertaining to specific and nuanced elements within the video, such as a character’s attire or a subtle expression. In contrast, traditional comments are typically generated subsequent to viewing the entire video, enabling a more macro-level and all-encompassing evaluation. Such micro-level quality, specificity, and a heightened potential for resonance are essential for audience’s gratifications.

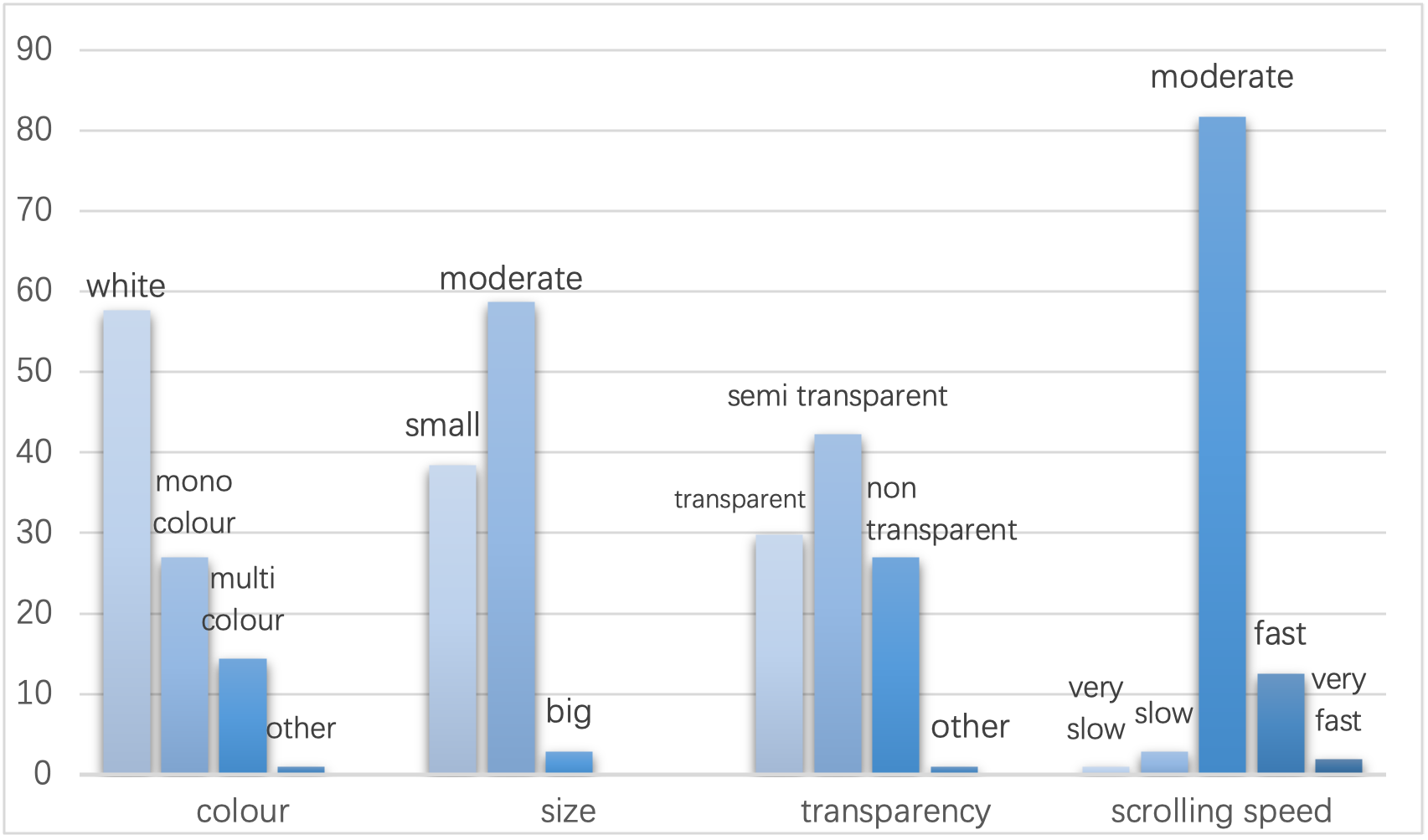

5.2 Gratifications towards danmu with different modalities

Table 8 and Figure 2 respectively show participants’ degree of gratifications to danmu with different modalities and their favourite setting for each modality. By comparing the mean rating across different modalities, scrolling speed (5.81) and size (5.79) matter most to viewers gratifications, followed by transparency (5.56) and colour (5.27). For scrolling speed, the most favourite setting is moderate (81.73%); for size, the most favourite setting is moderate (58.65%), followed by smaller (38.46%). Both the moderate settings for scrolling speed and size are Bilibili’s default setting, which show that the platform’s default setting is generally in line with the majority of viewers’ preferences.

Figure 2. Survey results of participants’ favourite setting for each modality

Proper scrolling speed and size may enhance the visibility and legibility of the danmu, making it easier for viewers to read and engage with the content, enhancing the overall viewing experience and engagement.

| Means | Median | %1 | 2% | 3% | 4% | 5% | 6% | 7% | Sd | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colour | 5.27 | 5 | 0.96 | 2.88 | 9.62 | 13.46 | 26.92 | 20.19 | 25.96 | 1.46 |

| Size | 5.79 | 6 | 0 | 0.96 | 3.85 | 14.42 | 18.27 | 21.15 | 41.35 | 1.38 |

| Transpa-rency | 5.56 | 6 | 1.92 | 0 | 5.77 | 14.42 | 19.23 | 27.88 | 30.77 | 1.28 |

| Scrolling speed | 5.81 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 4.81 | 13.46 | 19.23 | 21.15 | 41.35 | 1.25 |

Table 8. Survey results of gratifications towards danmu with different modalities

The modality of colour, however, ranked as the lowest factor that may influence viewing gratifications in this study. The favourite setting for colour is white (57.69%), followed by mono-colour (26.86%) and multiple-colour (14.42%). We may not conclude that colour is not as important as other factors, as the reason for this result might be the fact that multiple-colour danmu can only be sent by advanced users, thus causing a significantly smaller number than those white and mono-colour danmu. Multi-colour danmu may draw excessive attention and distract viewers from focusing on the main video content. If the colours are too vibrant and unobtrusive, they can become visually overwhelming and detract from the viewing experience. The content and context of the videos may also influence the viewers’ perception of colour in danmu. As the selected video was created by Youzimu, a fansubbing community, its production of conventional subtitles differs dramatically from subtitles used in mainstream streaming TV such as iQiyi and Youku. Youzimu used a bright blue colour for thematic consistency and channel identity, occasionally followed by bright yellow notes and glosses. Thus as the conventional subtitles are already presented in a colourful way, viewers may prefer a less deviating form for danmu. Uses and gratifications theory emphasises individual agency and control over media consumption to gain gratifications. Viewers may personalise their viewing experience by adjusting the display settings in other aspects such as size or scrolling speed over the choice of colours.

5.3 (Dis)connections between danmu and conventional subtitles

Table 9 shows results to the open-ended question “when would you frequently read danmu?” based on text frequency analyser. The responses were divided into three major themes: for comprehension, for resonation (i.e. something that evokes a strong emotional response with other people, often in a way that is deeply felt and understood), and for fun. The most frequently mentioned words in ‘for comprehension’ appear to corelate to the results in 5.1, where participants may seek extra information via danmu when they do not fully comprehend the video content. However, when we further sorted out the responses, it seems that we do not find a significant connection between danmu and conventional subtitles. According to the text frequency analyser and manual coding, only 3 participants mentioned “conventional subtitles” in their responses: “when I don’t understand the conventional subtitles”, “the conventional subtitles have very little information”, and “don’t know what the conventional subtitles say”. However, the keywords such as “video content itself” or “video genre” occur frequently in participants’ responses. Based on these results, we may infer that whether there is a connection between conventional subtitles and danmu depends on the content or genre of the video. If, for example, the content of a video is difficult to understand or contains a large amount of information, viewers may not find sufficient explanations in the existing conventional subtitles. In such cases, they will seek help in danmu to better understand the video. Alternatively, if the video itself belongs to the comedy/funny/spoof videos and whether or not they read the conventional subtitles does not affect their understanding, viewers will spend a significant amount of time reading danmu to satisfy their desire for amusement.

| Keywords | Frequency | Examples | |

|---|---|---|---|

| for comprehension | don’t understand 看不懂/不明白 |

11 | 想看文化背景等知识补充的时 候 (when waiting to see supplementary knowledge about cultural background) 需要弹幕辅助说明视频内容时 (when needing danmu to provide additional explanations for video content) 出现知识盲区时 (when encountering knowledge blind zone) |

| knowledge知识 | 5 | ||

amount of information 信息量 |

4 | ||

cultural background 文化背景 |

4 | ||

| blind zone盲区 | 3 | ||

| unfamiliarity陌生 | 3 | ||

| interpretation解说 | 2 | ||

| complementary辅助/补充 | 2 | ||

| for resonation | climax高潮 | 8 | 情节高潮时看看别人怎么想的 (during the climax of the plot, to see what others think) 想要得到共鸣 (when seeking resonance) 会想在弹幕找找是否有相同想 法的观众 (when wanting to see if there are are other viewers with similar thoughts) |

other viewers 其他观众/其他人 |

7 | ||

| resonation共鸣 | 4 | ||

| loneliness寂寞 | 3 | ||

| alone一个人 | 2 | ||

| interaction互动 | 2 | ||

| for fun | funny有趣/搞笑/好玩 | 12 | 看到有趣内容的时候 (when coming across interesting points) 视频中出现有梗的瞬间 (during the moments that have jokes) 看到还有别人同时在线,很治 愈 (when seeing others online simultaneously, it’s quite healing) |

look for amusement 找乐子 |

3 | ||

| jokes梗 | 3 | ||

| healing治愈 | 2 |

Table 9. Frequency results of keywords to the open-ended question “when would you frequently read danmu?”

The results of means to the two Likert scale questions (“I watch danmu because sometimes translation is not correct and danmu can provide more accurate explanation” and “I watch danmu because translation has a limited number of words and danmu could provide more additional background information/cultural knowledge”) are 5.01 and 5.16, implying that there might be some connections between danmu and conventional subtitles in terms of translation errors and cultural references. Since the selected video is an English video that involves cultural knowledge about British royal weddings, viewers may encounter culture-specific terms during the watching process. Subtitling culture-specific terms has always been a challenge in audiovisual products due to technical constraints (Ramière, 2006). The emergence of danmu, however, provides an alternative solution to this challenge: by reading real-time danmu at specific time points, viewers can timely gain additional cultural knowledge, which helps them better understand the video content while also experiencing a sense of foreignness.

6. Conclusion

In the present study, we used a video clip on Bilibili to examine audience’s engagement with and gratifications of the presence of different types of danmu, and also shed light on the potential (dis)connections between the audience reception of danmu and conventional subtitles. Based on the findings, extra cultural information danmu stand out as the most gratifying type among the other three types (tucao, short commentary, translation danmu), though not dramatically, satisfying viewers’ utilitarian and hedonic needs for information and entertainment seeking. Social interactivity and peer pressure needs linked to tucao and short commentary danmu also matter to viewer’s gratifications as viewers may find like-minded people, share similar thoughts, and resonate with others to foster a sense of collective identification and connection.

As for the different modalities, scrolling speed and size are the two most influential factors. Proper scrolling speed and size appear to enhance the visibility and legibility of danmu, making it easier for viewers to read and engage with the content. The platform’s default settings for scrolling speed, size, colour and transparency align with the majority of viewers' preferences. However, there is no significant connection found between danmu and conventional subtitles, suggesting that the potential connection between the two depends on the video’s content or genre. When the content is difficult to understand or lacks sufficient explanations in conventional subtitles, viewers may turn to danmu for help. While in comedy or funny videos, viewers may skip a large amount of conventional subtitles and spend more time on reading danmu for amusement, regardless of their impact on understanding the video.

The participatory real-time viewing experience and the unique expression of danmu tend to change the audience’s way of consuming videos. This study highlights the importance of extra cultural information danmu in satisfying viewers’ information and entertainment-seeking needs, and also underscores the significance of scrolling speed and size in optimising the legibility of danmu. Our research enriches the danmu literature by providing empirical insights into the audience reception towards using an online video-watching experiment to examine the impact of different types of danmu on viewers’ perception and gratifications. The results of this study may inform the design and implementation of danmu technology-enabled and user-generated features to enhance viewing experience. For example, it is suggested that a filtering setting may be improved to divide danmu into different categories based on their content and enable viewers to select the one they prefer. Further studies can be conducted with videos in different genres, or benefit from using eye tracking tools to capture the cognitive data of viewing behaviour in different types of danmu.

Acknowledgements

We extend our sincere gratitude to all the participants who contributed their valuable time to complete our experiment. We also wish to express our appreciation to the three anonymous reviewers and editors for their constructive feedback, which significantly enhanced the quality of this paper.

References

Bossen, B., & Kottasz, C. (2020). Uses and gratifications sought by pre-adolescent and adolescent TikTok consumers. Young Consumers, 21(4), 463-478.

Buf, D., & Ștefăniță, O. (2020). Uses and gratifications of YouTube: A Comparative Analysis of Users and Content Creators. Romanian Journal of Communication and Public Relations, 22(2), 75-89. https://doi.org/10.21018/rjcpr.2020.2.301

Cao, X. (2021). Bullet screens (danmu): texting, online streaming, and the spectacle of social inequality on Chinese social networks. Theory, Culture & Society, 38(3), 29-49. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276419877675

Chen, G. M. (2011). Tweet this: A uses and gratifications perspective on how active Twitter gratifies a need to connect with others. Computers in Human Behaviour, 27, 755–762. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.10.023

Chen, Y., Cao, S., & Wang, T. (2013). Danmu websites and danmu users: a youth subculture perspective [透视弹幕网站与弹幕族:一个青年亚文化视角]. Youth Exploration [青年探索], 2013(6), 19-24.

Chen, Y., Gao, Q., & Rau, P. (2015). Understanding gratifications of watching danmaku videos – videos with overlaid comments. Cross-Cultural Design Methods, Practice and Impact, 9180, 153-163. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-20907-4_14

Chen, Y., Gao, Q., & Rau, P. (2017). Watching a movie alone yet together: understanding reasons for watching danmaku videos. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 33(9), 731-743. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2017.1282187

Chen, Z. T. (2021). Poetic prosumption of animation, comic, game and novel in a post-socialist China: A case of a popular video-sharing social media Bilibili as heterotopia. Journal of Consumer Culture, 21(2), 257-277. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469540518787574

Debord, G. (2014). The Society of the Spectacle, trans. K. Knabb. Berkeley, CA: Bureau of Public Secrets.

Dennis, A. R., Fuller, R. M., & Valacich, J. S. (2008). Media, tasks, and communication processes: A theory of media synchronicity. MIS quarterly, 32(3), 575–600.

Elliot, P. (1974). Uses and gratifications research: a critique and sociological alternative. In J. Blumler and E. Katz (Eds.), The Uses of Mass Communications: Current Perspectives in Gratifications Research (pp. 249-268). Sage.

Finstad, K. (2010). Response interpolation and scale sensitivity: evidence against 5-point scales. Usability Metric for User Experience, 5(3), 104-110.

Hamasaki, M., Takeda, H., Hope, T., & Nishimura, T. (2009). Network analysis of an emergent massively collaborative creation community. Proceedings of the Third International ICWSM Conference (2009), 222–225.

Johnson, D. (2013). Polyphonic/pseudo-synchronic: animated writing in the comment feed of Nicovideo. Japanese Studies, 33(3), 297–313. https://doi.org/10.1080/10371397.2013.859982

Katz, E., Blumler, J. G., & Gurevitch, M. (1974). Utilisation of mass communication by the individual. In J. G. Blumler, & E. Katz (Eds.), The Uses of Mass Communications: Current Perspectives on Gratifications Research (pp. 19–32). Sage.

Khan, M. (2017). Social media engagement: What motivates user participation and consumption on YouTube? Computers in Human behaviour, 66, 236-247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.09.024

Kress, G., & Van Leeuwen, T. (2001). Multimodal discourse: The modes and media of contemporary communication. Arnold.

Li, J. (2017). The Interface affect of a contact zone: danmaku on video-streaming platforms. Asiascape: Digital Asia, 4, 233–256.

Li, H., & Wang, W. (2015). The barrage video: a new orientation about online video interactive learning [弹幕视频:在线视频互动学习新取向]. Modern Educational Technology [当代教育技术], 25(6), 12-17.

Lin, X., Huang, M., & Cordie, L. (2018). An exploratory study: using danmaku in online video-based lectures. Educational Media International, 55(3), 273-286. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523987.2018.1512447

Liu, L., Suh, A., & Wagner, C. (2016). Watching online videos interactively: the impact of media capabilities in Chinese danmaku video sites. Chinese Journal of Communication, 9(3), 283-303. https://doi.org/10.1080/17544750.2016.1202853

Lucas, K., & Sherry, J. L. (2004). Sex differences in video game play: a communication-based explanation. Communication Research, 31, 499-523. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650204267930

Ma, Z., and Ge, J. (2014). Analysis of Japanese animation’s overlaid comment (danmu): a perspective of parasocial interaction. Chinese Journal of Journalism and Communication, 8, 116–130.

Nakajima, S. (2019). The Sociability of Millennials in cyberspace: a comparative analysis of barrage subtitling in Nico Nico Douga and Bilibili. In Frangville, V., & Gaffric, G. (Eds), China’s Youth Cultures and Collective Spaces (pp. 98-115). Routledge.

Ouyang, Z., & Zhao, X. (2016). Bullet-curtain comments based on the time axis of video: peculiarities and limitations [视频时间轴的弹幕评论:特点与局限刍议].Journal of Chongqing University of Posts and Telecommunications (Social Science Edition) [重庆邮电大学学报(社会科学版)], 28 (4), 136–142.

Ramiere, N. (2006). Reaching a foreign audience: cultural transfers in audiovisual translation. The Journal of Specialised Translation, 6, 152-166.

Rubin, A. M. (2009). The uses-and-gratifications perspective on media effects. In J. Bryant & M. B. Oliver (Eds.), Media effects: Advances in theory and research (3rd ed., pp. 165-182). Routledge.

Stafford, T. F., Stafford, M. R., & Schkade, L. L. (2004). Determining uses and gratifications for the Internet. Decision Sciences, 35, 259–288. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.00117315.2004.02524.x

Sundar, S. S. (2008). The MAIN model: A heuristic approach to understanding technology effects on credibility. In M. J. Metzger & A. J. Flanagin (Eds.), Digital Media, Youth, and Credibility (pp. 72–100). MIT Press.

Sundar, S. S. & Anthony M. Limperos (2013). Uses and grats 2.0: new gratifications for new media, Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 57(4), 504-525. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2013.845827

Sung, Y. et al. (2016). CRIE: An automated analyser for Chinese texts. Behaviour Research Methods, 48(4), 1238-1251. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-015-0649-1

Xu, Y. (2016). The postmodern aesthetic of Chinese online comment cultures. Communication and the Public, 1(4), 436–451. https://doi.org/10.1177/2057047316677839

Yang, T., Yang, F. & Men, J. (2021). The impact of danmu technological features on consumer loyalty intention toward recommendation vlogs: a perspective from social presence and immersion. Information Technology & People, 35(4), 1193-1218.

Yang, Y. (2021). Danmaku subtitling: an exploratory study of a new grassroots translation practice on Chinese video-sharing websites. Translation Studies, 14(1), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1080/14781700.2019.1664318

Yoo, C. Y. (2011). Modeling audience interactivity as the gratification-seeking process in online newspapers. Communication Theory, 21, 67–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2010.01376.x

Youzimu. (2018, May 27). How Does the British Royal Family Prepare for a Wedding? [Video] Bilibili. https://www.bilibili.com/video/BV1Ap411d7Y8/?spm_id_from=333.999.0.0&vd_source=bcf49b66e1bcd8614840aec394772cd4

Youzimu. (2019, October 25). The Thoisoi2 Periodic Table: Berkelium – Likely the Least Reactive Metal on Earth. [Video] Bilibili. https://www.bilibili.com/video/BV1KE41117GY/?spm_id_from=333.999.0.0&vd_source=bcf49b66e1bcd8614840aec394772cd4

Youzimu. (2022a, October 21). Taylor Swift - Anti-Hero (Official MV). [Video] Bilibili. https://www.bilibili.com/video/BV1hm4y1w7Mt/?spm_id_from=333.999.0.0&vd_source=bcf49b66e1bcd8614840aec394772cd4

Youzimu. (2022b, October 26). Cure Vlog: Japan's First Miniature Pig Café Where You Can Pet Pigs. [Video] Bilibili. https://www.bilibili.com/video/BV1vW4y1E7C9/?spm_id_from=333.999.0.0&vd_source=bcf49b66e1bcd8614840aec394772cd4

Youzimu. (2022c, November 13). Texas Dallas Airshow: P-63 Fighter Plane and B-17 Bomber Collide and Crash During Flight Demonstration. [Video] Bilibili. https://www.bilibili.com/video/BV11G4y1t7op/?spm_id_from=333.999.0.0&vd_source=bcf49b66e1bcd8614840aec394772cd4

Zhang, T., & Cassany, D. (2019) The murderer is him ✓: multimodal humor in danmu video comments. Internet Pragmatics, 4(2), 272-294. https://doi.org/10.1075/ip.00038.zha

Zhang, L. T., & Cassany, D. (2020). Making sense of danmu: coherence in massive anonymous chats on Bilibili.com. Discourse Studies, 22(4), 483-502. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445620940051

Zhu. Y. (2017). Intertextuality, cybersubculture, and the creation of an alternative public space: ‘Danmu’ and film viewing on the Bilibili.com website, a case study. European Journal of Media Studies, 6(2), 37–54. DOI: 10.25969/mediarep/3399.

Data availability statement

The data pertinent to this research is not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise confidentiality and privacy of research participants.

Disclaimer

The authors are responsible for obtaining permission to use any copyrighted material contained in their article and/or verify whether they may claim fair use.

ORCID 0000-0001-9809-1059, e-mail: sijing.lu@warwick.ac.uk↩︎

ORCID 0000-0001-6085-6706, e-mail: chenx@wfu.edu↩︎

The term “danmu subtitled video" we used here encompasses all videos featuring danmu. It is important to note that within this context, the term "subtitled" does not necessarily denote a translational practice. In fact, the act of "subtitling" may cover various practices beyond translation, such as intralingual subtitles aimed at enhancing communication and readability.↩︎

For the purpose of this study, we define conventional subtitles as the subtitles that are normally located at the bottom centre of the screen, interpreting the lines of dialogue intralingually or interlingually. They might be transcripts of the screenplay, translations of it, or materials to aid hard-of-hearing or deaf audiences in understanding what is being displayed.↩︎