Activist subtitling narrates liminoid experiences countering ISIS post-Arab Spring—Daya alTaseh and The Bigh daddy Show

Mennatallah Mansi1, University of Galway

ABSTRACT

This paper examines activist subtitling practices in light of the two sociological concepts of narrativity and liminality. With particular focus on online contemporary activist communities that counter extremism, subtitling is studied as part of the cultural liminoid practices that produce and disseminate alternative narratives challenging the rigid frames of global jihadism. Launched as reactions to the repercussions of the Arab Spring and the establishment of the so-called Islamic State in Iraq and Syria, ضايعة الطاسة Daya alTaseh and ذا بيج دادي شوو The Bigh daddy Show are two activist online media initiatives that spread counter-jihadist narratives in Arabic subtitled in English. The study attempts to investigate the narratives mediated in the subtitles and their reflections of liminality. The subtitling in both initiatives is scrutinised and compared using a two-fold theoretical framework combining the socio-narrative theory in translation studies and theories on activist translation. Guided by this framework, the paper applies a descriptive qualitative analysis to data collected from observations and interviews. The data analysis reveals the distinct liminoid stories of Daya alTaseh and The Bigh daddy Show as narrated in the English subtitles, pinpointing the similarities and differences between them. User interaction with both initiatives is also highlighted as a contributor to the development of the subtitling process.

KEYWORDS

Activist subtitling, liminality, liminoid, counter extremism, narrativity, knowledge production

1. Introduction

The cultural descriptive approach to translation studies has opened the scope for studying translation, not as a mere linguistic transfer between two languages, but rather as a process of knowledge production (St-Pierre & Kar, 2007; D’hulst & Gambier, 2018; Conway, 2019; Hermans, 2019). Such a process is shaped by different factors including temporal and spatial dimensions, socio-political context, agents, as well as receiving audience. This has led to academic discussions on the translator’s agency, translation as rewriting or re-narration, and translation in relation to power and conflicts (Venuti, 1995; Baker, 2006a, 2013, 2014; Tymoczko, 2000, 2010a). “Translation is thus understood as a form of (re-)narration that constructs rather than represents the events and characters it re-narrates in another language” (Baker, 2014, p. 159). Thus, the agency and visibility of translators are more underlined; being “as much as creative writers and politicians in the powerful acts that create knowledge and shape culture” (Tymoczko & Gentzler, 2002, p. xxiii). Under the same approach, activist translation—the subject matter of this paper—is explored as an ideologically driven subversive act that challenges dominant discourses and seeks social or political change (Baker, 2006b; Pérez-González, 2010, 2012, 2017; Díaz-Cintas, 2018).

Activist translation has been part and parcel of the flow of knowledge and experiences that accompanied and followed the Arab Spring across borders (Mehrez, 2012; Baker, 2015; Selim, 2016; Zekraoui, 2017; Al-Mohammad, 2020). The mentioned previous literature discussed the role of activist translation in mediating the alternative narratives of resistant or revolutionary groups as opposed to those of the state or the mainstream. Activist translation or subtitling in other contexts created post-Arab Spring was rarely discussed. To fill in this gap, the paper investigates the activist subtitling of online video productions that counter the extremist jihadist ideology which resurfaced in 2014 with the introduction of the new ferocious face of global jihad: the alleged Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS). While global jihadists, represented by ISIS herein, cannot be described as mainstream, they compose an active movement that sought and attained authority for a while in parts of Syria and Iraq during the turmoil that followed the Arab Spring revolutions. Hence the paper pursues the discussion of the role translation plays in narrating counter-ISIS stories post-Arab Spring; not to mention that translation has been a main part of ISIS jihadist online propaganda (Lieberman, 2017; Wright et al., 2016; El-Araby, 2016).

Another addition made by this paper is discussing narrativity and activist translation in relation to the sociological concepts of liminality and liminoid (Turner, 1969/2002, 1974). Applied widely in social and political sciences to explore and understand transitional phases of change in the contemporary world, liminality is defined as a condition characterised by transition and uncertainty; being “betwixt and between the positions assigned and arrayed by law, custom, convention, and ceremonial” (Turner, 1969/2002, p. 359). Liminoid, on the other hand, is a concept coined by Turner (1974) to understand the cultural knowledge, practices and experiences created during modern uncertain moments. Liminoid cultural activities are described as “an independent and critical source,” “an independent domain of creative activity” and “a plurality of alternative models for living” (Turner, 1974, p. 65). With recourse to these concepts, the paper explains the socio-political dynamics of cultural production post-Arab Spring; being a transitional uncertain phase that witnessed diverse cultural activities (liminoids). Activist translation is crystalised as part of this cultural production through narrating liminoids in other languages.

Two examples of counter-jihadist productions are tackled in this paper: Daya alTaseh and The Bigh daddy Show—hereinafter referred to as DT and BDS, respectively. They are two online media channels producing Arabic videos that criticise ISIS jihadist ideology subtitled in English. Scrutinising the subtitling of counter-ISIS videos produced by DT and BDS, this paper aims to examine aspects of liminality and knowledge production in the mediated narratives. The paper searches for an answer to a main research question: How does activist subtitling of DT and BDS online counter-ISIS productions narrate their distinct liminoid experiences post-Arab Spring? Under this question, the following sub-questions are discussed: What contribution did the digital platform and user interactions make to the subtitling process? What kind of positioning do the mediated narratives tell about the agents in relation to their socio-political surroundings? How do the subtitling modes and strategies used shape the different liminoid experiences in the mediated narratives? To answer these questions, the paper examines linguistic and qualitative data collected through two methods: 1) observation of the subtitled products, online platforms and user-interactions and 2) interviews with founders/members of the two online media initiatives. The data analysis is guided by a two-fold theoretical framework combining socio-narrative theory in translation studies (Somers & Gibson, 1993; Bruner, 1991; Baker, 2006a) and theories on activist translation communities (Baker, 2006b; Pérez-González, 2010, 2012, 2017; Pérez-González & Susam-Saraeva, 2012).

The paper starts by outlining narrativity and activist translation. A detailed discussion of the socio-narrative theory in translation studies is presented with the derived methodological and analytical tools. A review is also given expounding the theoretical literature on activist translation practices and communities. Then, the paper offers an analytical comparison of the subtitling of the video productions in the two online initiatives under scrutiny (DT and BDS), examining how the subtitles narrate their distinct liminoid stories.

2. Narrativity and activist translation

Narratives, according to the sociological approach, constitute our identity and understanding of the world around us; they do not represent reality, but rather are essential constituents of it (Somers & Gibson, 1993, p. 27; Bruner, 1991, p. 5). Nothing is interpretable and comprehensible without the narrative in which it is embedded. The same scattered events can be interpreted differently depending on the narrative into which they are interwoven or framed. Narratives are shaped by the time and space in which a selection of events are embedded, the relationships they have with their socio-political surroundings, and the employment of these independently selected events to give meaning (Somers & Gibson, 1993, p. 28). Narratives in their sociological sense are of great significance to the study of translation practices during times of conflicts and disruption. Amid the fluidity of knowledge production and transfer among different cultures facilitated by ICT, the immense value of translation is underlined as a re-narration of events (Baker, 2006a, 2007, 2014) within spaces created out of conflicts or revolutions. Different players (state regimes, power blocs, activist collectives or individuals) use translation “to legitimize their version of events” (Baker, 2006a, p. 1). The socio-narrative approach allows to “explain translational choices in relation to wider social and political context, but without losing sight of the individual text and event” (Baker, 2007, p. 154). It also provides tools to study translations in relation to the power play between the dominant and the resistant or the mainstream and the marginal (Baker, 2006a, p. 23).

Since the paper investigates activist subtitling of counter-ISIS videos produced during the disruptive period that followed the Arab Spring, the socio-narrative approach is found to be a suitable theoretical framework. Activist subtitling herein is viewed as a narration of alternative voices that challenge the extremist doctrines and ideological thoughts of ISIS, when the extremist group took control over several areas in the Arab world. In this sense, the subtitling practices of concern here fall under Tymoczko’s (2010b) description of activist translation as “a means of fighting” oppression, coercion and dominance (p. 3). These practices also fit Baker’s (2006b) description of activist translation as enabling the elaboration of alternative views of events across national and linguistic boundaries, challenging dominant discourses (p. 481). Similarly, they align with Díaz-Cintas’ (2018) definition of activist or guerrilla subtitles as “subtitles that are produced by individuals or collectives highly engaged in political causes, with the objective of combating censorship and conformity by spreading certain narratives that counter-argue the truth reported by the powerful mass media” (p. 134). By using the socio-narrative theory, the paper aspires not only to scrutinise the counter-ISIS narratives produced in the subtitles, but also to explore how the subtitles reflect the distinct experiences of the two groups (DS and BDS) who produced the videos.

Building upon the socio-definition of narrative discussed above, scholarly work in translation studies (Baker, 2006a, 2006b, 2007, 2014; Boéri, 2008; Harding, 2012; Jones, 2019) has discussed and examined different methodological frameworks applicable to the analysis of translation beyond the mere linguistic level. This paper relies on Baker’s (2006a, 2006b, 2007, 2014) postulation of the analytical tools derived from the socio-narrative theory (Somers & Gibson, 1993; Bruner, 1991) and applied to translation studies. For the purposes of the paper, the socio-narrative features outlined are the four identifying features introduced by Somers and Gibson (1993): temporality, relationality of parts, causal emplotment, and selective appropriation. In addition, canonicity and breach, one of the narrative features discussed by Bruner (1991), is included in this outline, due to the relevance of this feature with the innovation that usually characterises activist translation, as elaborated further below in this section.

First, the temporality feature deals with two aspects: the specific temporal and spatial configuration of events and historical references in recent narratives (Baker, 2006a; pp. 51, 55). Having a different temporal or spatial context or omitting a historical reference in the translation can produce new meanings in the mediated narratives. Second, relationality means that isolated events cannot have a meaning outside a narrative (p. 61). The meaning of each event is constituted in relation to the overall narrative in which it is embedded. This can be troublesome when the network of public and meta narratives in the target culture is quite different from that of the source. Relationality has also to do with participants’ positioning in relation to each other and those outside, and any change in this positioning changes the meaning (p. 132). Third, causal emplotment analyses how ‘facts’ or ‘instances’ are explained in relation to each other in a given narrative and how much significance or weighing is given to each of them (pp. 67-68). This helps in examining a translated narrative in terms of the arrangement of events leading to a certain emplotment or conclusion, as well as the elements accentuated or suppressed. Fourth, selective appropriation is the inclusion of certain instances or events and the exclusion of others (p. 71). This feature contributes to the examination of instances of addition and omission in translation and the resulting effects they have on the translated narrative. Fifth, canonicity and breach relate to instances of innovation in a narrative that break away from the established canons (p. 98). This feature of narrativity goes in line with the novelty and innovation that characterise activist translation. Orrego-Carmona and Lee (2017) describe non-professional user-generated translation practices, including activist translation, as “disruptive” to established norms and concepts (p. 5). These types of translation practices “facilitate the absorption of some (hitherto) marginal content into the fabric of the mainstream cultural industries” (Pérez-González, 2017, p. 15).

The socio-narrative theory offers a second set of useful analytical tools, namely narrative typology (Baker, 2006a). There are four types of narratives from the sociological perspective. First, ontological or personal narratives stand for stories used to define the self, and in turn how to act (p. 28); an example relevant to this paper is the ontological narratives of Arab immigrants in the aftermath of the Arab Spring and the rise of ISIS. Second, public narratives are those of formations larger than the individual like an organisation, religious institution or nation (p. 33), for instance public narratives on the Arab Spring. Third, conceptual narratives are concepts and explanations by scholars (p. 39); examples pertinent to this study are concepts related to Islamic Sharyʿa such as kufr ‘infidelity’, ridda ‘apostasy’ and shahada ‘martyrdom’. Fourth, meta or master narratives are those stories extending beyond geographical borders (p. 44) like Islamism, nationalism and terrorism.

Another theoretical framework of value to this paper is theories on activist translation communities. According to Baker (2006b), activist translators are those individuals or collectives who engage in translation practices according to their narrative affinity (p. 463). They volunteer to voice and disseminate a certain narrative of events across borders, to gain networks of support and solidarity. Activist translators can belong to different backgrounds: professional experienced translators/interpreters, students or teachers of translation or even unskilled amateurs (Baker, 2013, p. 36). They represent one of the categories of non-professional translators discussed by Pérez-González and Susam-Saraeva (2012) who “are more prepared to ‘innovate’, play around with the material in hand,” which reflects “their sense of initiative, authority and agency” (p. 158). Two types of activist translation communities can be distinguished: generative and structuralist (Pérez-González, 2010). The latter involves a hierarchical structure and engagement based upon shared social, cultural or political affiliations; “discrete, static groupings of individuals clustered on the basis of mutual affinity and shared affiliation” (p. 261). In contrast, generative activist translators lack a hierarchical or static structure and engage in activist translation practices “irrespective of their positioning in the political and socio-cultural orders [. . .] engaging in activism on the basis of partial affinity with other network members” (p. 263).

A two-fold theoretical framework is derived from the theories reviewed above to address the argument of this paper on the activist subtitling of DT and BDS counter-ISIS videos. The developed framework allows for the analytical discussion to answer the questions raised on the different elements contributing to the subtitling process and how they reflect the liminality of the agents. Guided by this two-fold theoretical framework a data set of linguistic choices and qualitative data is analysed. The data was collected using two methods: observation and interviews. Observation of subtitled videos and online platforms was used to extract linguistic and qualitative data from: 1) the English subtitles of DT’s ISIS Sketches and BDS cartoon series on YouTube; 2) sections on DT and BDS official websites, Facebook pages or YouTube channels; 3) user-interaction with the subtitled videos on YouTube. The selection of YouTube as a platform for observation of the video subtitles and user-interaction with them is due to the significant presence of global audiences on the YouTube channels of both groups, as compared to their Facebook channels. On the other hand, interviews with founders/members of the initiatives (conducted by the researcher or published via online media channels) are used to collect qualitative data on the agents (including translators) and the subtitling process in general. For DT, the researcher conducted an online interview with Youssef Helali, one of the initiative directors and co-founders (personal communication, March 12, 2019). An informed consent was obtained from Helali to participate in this research on activist subtitling and to conduct the interview. Then, a written permission was given by him to publish the data collected during the interview, as part of the research. Meanwhile, published media interviews with BDS founders or activists (BBC Arabic, 2016; Domat, 2016) are referred to in the analysis, since it was not possible to reach them. The data set collected from observation and interviews are analysed using tools derived from the two-fold theoretical framework discussed above, as expounded in the next section.

3. Narrating liminoids in subtitles

The Arab Spring uprisings (2010-2013) have resulted in the creation of transitional uncertain phases within most Arab states (Tunisia, Egypt, Syria, Libya, Iraq etc.). The dynamics of these phases can be understood under Turner’s (1969/2002) conceptualization of a liminal society: “unstructured or rudimentarily structured and relatively undifferentiated comitatus, community” (p. 360). Liminality, as Thomassen (2009) laid out in his contemporary reading of the concept, can be applied to times (single moments to eras) of uncertainty and disruption involving crises, conflicts, wars or revolutions in specific areas, whole countries or continents, and lived by single individuals, groups or whole societies (p. 16). The Arab Spring wave resulted in liminal periods that are characterised by instability and fall of, or at least disruption in, established structured regimes, in pursuit of social, political and economic change. Consequently, new spontaneous networks of different contesting parties (supporters of old regimes, different political parties, revolutionists, Islamists, jihadists, engaged public, regional and international advocacy networks, etc.) have emerged and attempted to play an active, if not main, role in shaping the transitional post-Arab Spring phase.

Global jihadists were one of the main movements that developed within the condition of uncertainty and disruption prevailing post-Arab Spring. With the striking declaration of ISIS in 2014, different independent activist initiatives by Arab citizens emerged with the aim of criticising and questioning ISIS’s extremism and oppression. Two examples of such are DT and BDS that produce online video content to counter ISIS’s radical view of Islam and expose the jihadist group’s fabrications and atrocities. They are both manifestations of what is called by Turner (1974) ‘liminoid’: the experimental creative activity in art and leisure that is produced within moments of uncertainty and takes place on the margins of the society apart from the centre (pp. 85-86). Liminoid describes liminal experiences “where creativity and uncertainty unfold in art and leisure activities” (Thomassen, 2012, p. 27). Established in 2013, DT produces satirical online videos shedding light on social, political and economic events in Syria. DT video productions include Maʿnā ʾw ʿalynā ‘For or Against’, Nashrat Ghasyl ‘News Laundry’, Lā Tatahawwar ‘Don’t Rush’ and Skatshāt Daʿish ‘ISIS Sketches’. To address the subject matter of this paper (counter-extremism), only the subtitles of ISIS Sketches (released online as of the end of 2014) are scrutinised. DT videos are disseminated online via three digital channels:

its parent group United Pixels website (https://unitedpixels.media),

Facebook (https://www.facebook.com/DayaAltaseh.Media) and

YouTube (https://www.YouTube.com/user/DayaAltaseh).

On the other hand, BDS is a Disney-like cartoon series making fun of ISIS and its leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdāddy. The series, launched in early 2016, is published via two online channels:

Facebook (https://www.facebook.com/bighdaddyshow) and

YouTube (https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCtGjdrpcakgWdfAYKd2b4aw).

Activist subtitling was an essential part of the cultural production of both DT and BDS, as their Arabic counter-ISIS videos were subtitled into English and in some cases into French. This paper argues that activist subtitling in both initiatives was not just a medium of transferring their counter-ISIS view in other languages, but rather constructed their different liminoid experiences in the mediated narratives. To address this argument, the following analysis examines the narratives produced in the subtitling of DT and BDS counter-ISIS videos. The analysis is sectioned according to the five features of narrativity discussed in the previous section (temporality, relationality, selective appropriation and causal emplotment, canonicity and breach), which are the main analytical tools used. Other analytical auxiliary tools derived from the theoretical frameworks reviewed in the previous section (the narrative typology and the classification of activist translation communities) are also deployed to augment the analysis. These tools of analysis are used to scrutinise the data set collected from observation of subtitled products, platforms and user-interaction, as well as from interviews with DT and BDS founders/members. The analysis of the data set investigates whether the counter-ISIS narratives produced in the subtitles correspond with what DT and BDS tell about their liminoid experiences, and where the two groups meet or depart in their narratives.

Temporality

The spatial configuration of DT and BDS is a key element in the subtitling process. As both are hosted online, user interaction has been a main driver that steered and developed the subtitling of their video productions. Since DT release of counter-ISIS video sketches by the end of 2014 in Arabic, many users on its YouTube channel kept asking for English subtitles and other languages as well. Figure 1 illustrates some of the user comments requesting translation.

| Please, PLEASE provide with English subtitles, this is share-worthy stuff! :D |

| Please please provide english subt. |

| Translation please? |

| another great video [. . .] please would you dub or add subtitles |

| You should subtitle in English, and why not not in other languages |

Figure 1. User comments requesting translation (DT Videos YouTube)

As per observation of the DT YouTube channel, counter-ISIS sketches have received the highest number of requests for subtitles among the group’s various productions. It may be attributed to the topic itself (ISIS extremist ideology and violent activity) which links with similar personal and public narratives in many other countries, in addition to the fact that ISIS propaganda targets and reaches many parts of the globe. Responding to these requests, DT activists have added English subtitles to a number of counter-ISIS sketches and episodes using the YouTube subtitles tool. When asked about the subtitling process of counter-ISIS sketches and episodes, Helali (personal communication, March 12, 2019) said that “at the beginning, we did not consider translation or spreading our productions outside Syria or in another language besides Arabic [. …] Then we realized that if we are fighting terrorism in general, we have to widen our scope and target other communities.”

User interaction has contributed to the development of the subtitling process in BDS too, yet in another language pair. In contrast to DT, BDS released videos with English subtitles accounted for since production and considered the addition of subtitles in other languages as well. One BDS activist elaborated that they initially subtitled the videos in English because they wanted to reach everyone, adding that they wanted to add French subtitles as well whenever feasible (Domat, 2016). Compared to DT, fewer subtitling requests are detected on the BDS YouTube channel and mostly call for subtitles into French, as shown in Figure 2. Accordingly, BDS activists have provided French subtitles besides the already embedded English subtitles, using the YouTube subtitles tool.

| Comment |

Est-ce qu'il y en a avec sous- titres en français? Merci! ‘Are there any with French subtitles? Thank you!’ |

Traduction en français... pleeaase ! ‘French translation ... pleeaase!’ |

Figure 2. User comments requesting translation (BDS Videos YouTube)

It can be deduced that the online temporal and spatial configuration of both initiatives has fuelled the need to produce their liminoid experiences in other languages. In response, both initiatives have resorted to activist subtitling practices to communicate their counter-extremist knowledge to wider communities. Such online temporality has made the subtitling process subject to change all the time. This is manifested in the diverse user comments on the translation, whether positively or negatively, and in some cases suggesting edits, as illustrated in Figure 3.

| I loved this stuff [. . .] Waiting for new subtitles in other eps as soon as possible! |

| Very brave guys, thanks for the translation |

je sais pas si ca vient des trad'z, ou de l humour utilisé, mais je trouve pas ca drole. Meme si je dois l avouer [. . .] Continuez comme ça ! ‘I don't know if it comes from the translation, or from the humour used, but I don't find it funny. Even if I have to admit it [. . .] Continue like that!’ |

At 0:26 the word recived... should be spelled "received" Found another typo @ 0:51....peacfully should be "peacefully" |

Figure 3. User comments on subtitling (DT Videos YouTube; BDS Videos YouTube)

Furthermore, it can be postulated that the ephemeral temporality of the subtitles substantiates the uncertain liminal status of DT and BDS agents in the mediated narratives. Such liminal status is clear in their self-description as immigrants or living in areas of conflict. In an interview with the researcher, Youssef Helali, a DT co-founder and director, said that he and the other co-founder of the initiative, Maen Wasfy, are Syrian immigrants in Turkey and in the Netherlands, respectively, who met outside Syria and decided to cooperate to establish Daya alTaseh (personal communication, March 12, 2019). Similarly, in an interview published by the French news website Rue89 (Domat, 2016), one of the BDS activists said that they are either based in territories controlled or affected by ISIS or in other safer countries albeit feeling insecure. Accordingly, the online temporality of the subtitling process and its continuous subjection to adjustment and change—as explained above—correspond to the sense of liminality and fragmentation lived by the agents.

Relationality

Both initiatives’ names and their translation are of significance in identifying their distinct positionings in relation to their socio-political surroundings in the mediated narratives. Daya alTaseh ضايعة الطاسة ‘Lost Bowl’ is an Arabic idiomatic expression mostly used in the Levant area, to refer to a situation of chaos, disruption and uncertainty. The name of the Syrian initiative reflects the liminal condition following the 2011 uprising. The transliteration of the Arabic name into the Latin alphabet brings the Arab Syrian identity into focus and positions DT agents as nationally oriented. In contrast, The Bigh daddy Show ذا بيغ دادي شوو is based on the wordplay between ‘big daddy’, an American English idiomatic expression that refers to someone with outstanding paternalistic authority, and ‘Baghdāddy’, the last name of ISIS Caliph Abu Bakr al-Baghdāddy. It is also worth noting that various American iconic figures (wrestlers), shows (reality TV) and films (a 1999 comedy film starring Adam Sandler) are called “Big Daddy”, making the expression common globally. Choosing an English title and transliterating it into Arabic conceal the national identity of activists and relate the mediated narratives to a cosmopolitan community.

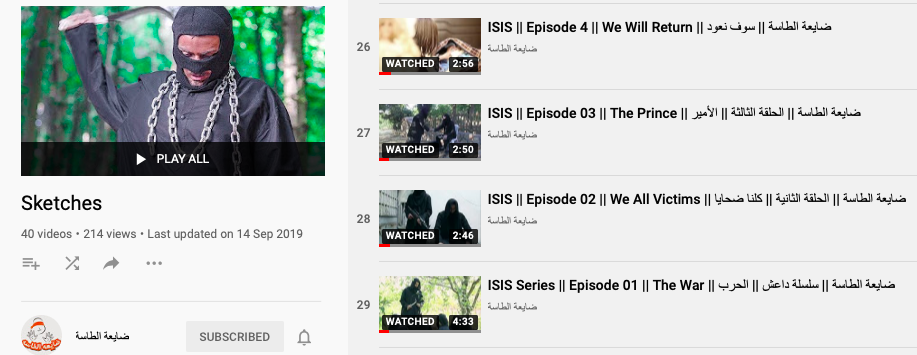

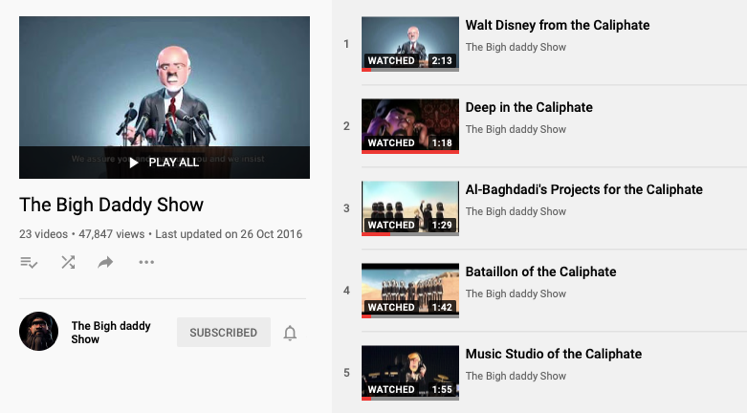

The language of online posts narrates the same positionings of DT and BDS as national vs cosmopolitan. DT posts the About section in Arabic on both YouTube and Facebook channels and keeps the English version to the website (United Pixels), which was not live until 2018. In contrast, BDS defines itself in English only on its YouTube channel, while adding an Arabic translation of the About section on its Facebook page, which is followed mostly by a local audience. The use of Arabic by DT and English by BDS echo their distinct positionings; being national-oriented and cosmopolitan-oriented, respectively. The same point is observed in the language(s) of posting the titles of the sketches and episodes on DT and BDS social media channels. DT posts the titles of videos in English and Arabic side by side, as shown in Figure 4, on both YouTube and Facebook channels. In contrast, BDS keeps the Arabic titles and hashtags on its Facebook channel, while, on YouTube—where global audience participation is relatively higher—suffices with the English titles, as shown in Figure 5, with the French translation of titles added in some episodes.

Figure 4. DT sketch titles posted in both English and Arabic (DT Sketches Playlist YouTube)

Figure 5. BDS episode titles posted in English only (BDS Playlists YouTube)

The dissimilar positionings of both groups in the mediated narratives are also resonant in their different modes of translation. Being a nationally oriented group, DT brings the Arab Syrian culture to the target text by adopting foreignization in the subtitling of counter-ISIS sketches. This is demonstrated in the literal rendering of expressions rooted in the source Arab culture, as exemplified in Figure 6. On the other hand, BDS adopts domestication in the subtitling of its cartoon series. As illustrated in Figure 6, BDS subtitles naturalise culture-bound terms and idioms in the target language, confirming their global cosmopolitan orientation in the mediated narratives.

| Idiom/expression | DT Subtitles |

هذا الكلام تقوله في بيت أمك ‘idiom used to refer to sissy talk’ |

This talk you say in your mother house |

وهل تعتقد بأن دخول دورة المياه مثل الخروج منها ‘idiom said when it is difficult to get out of trouble’ |

Do you thing [sic] that entering the bathroom is like getting out of it |

| Idiom/expression | BDS Subtitles |

سنرسل لكم عناصر من فصيلة الرؤوس المسطحة ‘literal translation: We will send you elements from flat head platoon’ |

We will also send you a platoon of dumbheads |

ملوخية .. آه زين زين ‘literal translation: Molokhiyya .. Yeah good’ |

Spinach??... yes good… |

كان مزحه ثقيل شوية ‘literal translation: He used to make bad jokes’ |

He used to be an asshole |

هذه مائدة الإفطار ‘literal translation: This is the breaking fast table’ |

This is the dining table (breaking fast table) |

Figure 6. Translation of idioms and culture-bound expressions (DT Videos YouTube; BDS Videos YouTube)

The above analysis posits that both liminoid experiences (DT & BDS) are narrated differently in the English subtitles in terms of relationality (positioning). While both groups align in mediating counter-ISIS narratives, they define themselves distinctively in relation to other participants and surroundings. The distinct positionings (DT national vs BDS cosmopolitan) in the English narratives match their About sections and interview statements. In DT website’s About section, the Syrian national identity is intensely stressed, with “Syria” and “Syrian” mentioned 16 times (United Pixels). The group sets its concern “to continue defending Syrian Human Rights” (United Pixels) and uses satire to shed light on concurrent Syrian issues (DT About Facebook). Thus, DT counter-ISIS sketches are embedded in relation to the overall public narratives demanding freedom and development for Syrians fuelled by the 2011 uprising. In contrast, the BDS About section stresses its cosmopolitan identity by removing any reference to nationality or place, stating its purpose as “Making fun of DAESH” (BDS About YouTube) and “We make ISIS look like real idiots” (BDS About Facebook). This embeds BDS counter-ISIS narratives in relation to the overall network of meta narratives of counter extremism and terrorism.

While the discussion above on the dissimilar positionings of DT and BDS agents is general, it can be applied in particular to the translators involved. With reference to Pérez-González’ (2010) classification of activist translation communities—discussed in section two—it may be concluded from the analysis above that DT follows a structuralist approach to activism. This is evident in their emphasis on their national socio-cultural affinity, as Arab Syrians. The same is also reiterated in Helali’s comments on DT volunteering circles, including translators, stating “most of them are acquaintances, friends or friends of friends, of known backgrounds” (personal communication, March 12, 2019). Unlike DT, the analysis indicates that BDS is more of a generative activist collective, the second type of Pérez-González’ (2010) classification. BDS narrative reflects no consideration of national, social, political or cultural affinities. They belong to different backgrounds, yet they share collectively a sense of insecurity that urged them to fight ISIS’s radical doctrines (Domat, 2016). Accordingly, it can be assumed that BDS agents, including translators, are mobilised based on a partially shared affinity against extremism represented in ISIS, yet they may have different national or socio-cultural backgrounds and ideological affiliations.

Selectivity & causal emplotment

While the opposite general translation modes adopted by DT and BDS show their different positionings in the mediated narratives, a similar translation strategy was deployed to subtitling Islamic terms and ideologically loaded words. It is observed in the subtitles of both initiatives that the Islamic religious register was selectively removed, and the nearest correspondences in the target language were used to mediate Islamic related terms and concepts. This contrasts with the transliteration strategy usually adopted by ISIS media propaganda2. As shown in Figure 7, words that relate to public and conceptual Islamic narratives in the source Arab culture are rendered into their English equivalents in both DT and BDS videos. Words such as "الله", "كفار", "القدس", "شهيد" said by ISIS characters, are subtitled in English as “God,” “infidels,” “Jerusalem,” and “Martyr,” as opposed to “Allah,” “Kuffār,” “al-Quds,” and “Shahid,” as usually found in ISIS English media. Translating these words into their equivalents omits the group’s alleged relation to Islam and Muslims in the mediated narratives.

| Word | Subtitles | ISIS Used Transliteration |

| المرتد | Apostate | Murtad |

| كفار | Infidels | Kuffār |

| الله | God | Allah |

| الجنة | Heaven | Jannah |

| الخلافة | Caliphate | Khilāfah |

| المجاهدين | Jihadis | Mujāhidīn |

| القدس | Jerusalem | al-Quds |

| رافضي | Shii | Rafidi |

| شهيد | Martyr | Shahid |

| الأناشيد الجهادية | Jihadi anthems | Nasheed |

Figure 7. Translation of Islamic terms and ideologically loaded words (DT Videos YouTube; BDS Videos YouTube)

Similarly, Figure 8 demonstrates various examples of omitting the Islamic religious register from the translated English narratives. For instance, “الأمير” ‘Amīr’ is subtitled in the videos of both counter-ISIS initiatives as “Prince,” “Commander” or “Lord” removing any Islamic historical connotations to the word. The word Amīr refers historically to a Muslim commander or local chief at the time of Muslim conquest. Silencing the Islamic register in the English subtitles promotes a narrative where the extremist group does not by any means relate to the Islamic religion or heritage, as claimed by them. The English narrative in the subtitles suggests that the group’s aims and purposes are merely focused on land and power. The same interpretation applies to the translation of the word “الدولة” ‘Islamic State’ to “this land” or “our land.” Neutralising the word in this example into just “land,” conveys ISIS political and economic interests, not religious aims as alleged by the group.

| Word | Subtitles |

| الأمير ‘Amīr’ | Prince, Commander or Lord |

| الدولة ‘Islamic State’ | this land or our land |

| توكل على الله ‘Trust in Allah’3 | Go ahead |

| اخوان ‘Muslim Brethren’ | Guys |

| محارمها ‘Maharim (plural of Mahram): refers to a man's close female relatives’4 | Her father, brother or husband |

Figure 8. Omitting religious register (DT Videos YouTube; BDS Videos YouTube)

As a result, the subtitled English narratives introduce a new emplotment of events to the English target audience whose mindset is influenced by the public and conceptual narratives of Islamophobia, Jihadism and Islamic Fundamentalism. By naturalising the Islamic terms and removing the Islamic register, the narratives plotted in the English subtitles disconnect the fundamentalist ideas and doctrines expressed by characters representing ISIS from Islam and its historical heritage to which the extremist group discourse constantly establishes relation. Correspondingly, the causal emplotment trajectory created in the mediated narratives restates the aim and mission of DT and BDS liminoid experiences: to counter ISIS propaganda. DT describes itself as “an alternative source of information” (United Pixels), as opposed to “other media groups,” referring to state media or extremist propaganda. Equally, BDS defines its cartoon series as an alternative contribution on social media channels, challenging, in particular, the dominance of ISIS jihadist propaganda (BBC Arabic, 2016).

Canonicity and breach

Featured by the amateurism and agency of activist subtitling practices, DT and BDS video subtitles exhibit various instances of innovation and creativity. Such instances do not only break away from the professional subtitling canons but also breach the rigid discourse of ISIS. As illustrated in Figure 9, DT subtitles contain non-standardised line breaks, abbreviations, capitalisation, misspellings and grammatical inconsistencies.

|

Non-standardised line breaks |

| u, ll, ’t, ’ve” | Abbreviations |

we’ve Captured the Twitter we will Kill the Twitter |

Capitalisation |

| Youuuu ..apostate infidel… | Elongation of vowels |

| Ware, Worrior | Misspelling |

that one of the commanders of free army will be exist in this region You are a thief and you must be retribution Which stole |

Grammatical errors |

Figure 9. Instances of amateurism and novelty in the subtitles (DT Videos YouTube)

Some of these instances (like misspellings and grammatical inconsistencies) could be attributed to the incompetence of activist translators. Others (like capitalisation and elongation of vowels) could be made to substantiate the sense of humour. Using this kind of casual innovative style, when conveying ISIS rigid canonical discourse, contributes to the construction of counter-ISIS narratives in the subtitles. For example, in one of DT’s sketches (DT, 2015, June 1), the characters acting as ISIS members decide to exterminate Twitter for blocking ISIS members’ accounts, so they grab a chicken, paint it in blue, and decide to kill it. In this scene, capitalisation is used in the subtitles with both words “Captured,” and “Kill” in “we’ve Captured the Twitter,” “we will Kill the Twitter,” and the definite article “the” is added to the proper noun “Twitter.” While the narratives mediated convey the extremist doctrines of ISIS through the words “[k]ill” and “[c]aptured,” the innovative subtitling strategies (capitalisation and grammatical inconsistency) breach the rigid messages they carry. As a result, the created narrative in the English version mocks ISIS extremism and superficial thinking, making them look like fools.

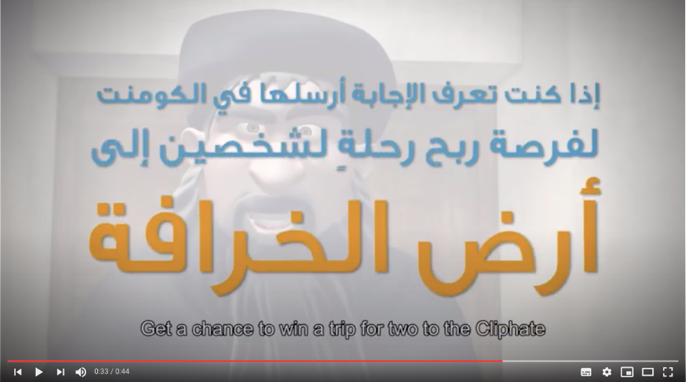

The same subversive innovative trend can be observed in the subtitles of BDS videos on YouTube. Two key words are played with in the English subtitles of the cartoon series: "الخلافة" ‘the caliphate’ which is misspelt in multiple instances as “Cliaphate/Cliphate” and also "البغدادي" ‘al-Baghdāddy’ transliterated as “Bigh daddy.” The manipulation in the spelling of these two key words shapes a mediated narrative that downplays the reverential frames ISIS establishes for its leader and the claimed Islamic State. The first is based on the play on words between two Arabic words "الخلافة" ‘the caliphate’ and "الخرافة" ‘Cliphate/Superstition’, which was mentioned in one of BDS episodes as shown in Figure 10. Aside from this occurrence, in multiple instances across BDS episodes, "الخلافة" was subtitled as “Cliaphate or Cliphate.” While ISIS claims glory and victory based on the allegation that its Caliphate or Khilāfah is an extension of the Islamic Golden Age, misspelling the word violates such a glorious frame, making the claimed ISIS “Cliaphate” a mere superstition. Similarly, whenever the name of the Khalifah "أبو بكر البغدادي" ‘Abu Bakr al-Baghdāddy’ is mentioned, the subtitles say “Bigh daddy,” echoing the name of the series. Whereas ISIS seemingly portrays the ‘Khalifah’ as a respectful religious authority, the play with word mocks and challenges such authoritative power in the mediated narratives. The use of “Bigh daddy” breaches also a core element in the alleged authority of ISIS Khalifah, as it erases his Islamic Arab identity. al-Baghdāddy (the Khalifah’s last name or Kunyah) is derived from Baghdad, the Capital of Iraq, where he comes from. Thus, this Arab reference is absent when the word is played with to be the “Bigh daddy.”

Figure 10. Instances of amateurism and novelty: word play (BDS, 2016, March 25)

It can be concluded that these instances of breach contributed to the construction of counter-ISIS narratives in the subtitles. Moreover, they substantiated the sense of humour in the mediated narratives, which is an inherent part of DT and BDS liminoid experiences. On the use of humour, Helali (personal communication, March 12, 2019) said: “We refuse to get involved in an internal militant fight that targets Syrians, instead we opt for comedy that is the best way to convey our message.” Likewise, in a published interview, one of BDS’s activists underlines that they opted for language and humour to speak more to the souls and to destroy the myth about strong ISIS fighters showing them as fools with big guns (Domat, 2016).

4. Conclusion

This paper has explored activist subtitling as a form of narration that tells the cultural liminoid experiences emerging post-Arab spring. It scrutinised the activist subtitling of online counter-ISIS videos produced by two different groups (DT and BDS). Although both activist initiatives are not translation centred, the subtitling of their counter-ISIS videos proved to be vital not only for conveying their counter-extremist views, but also their distinct experiences amid uncertainty and disruption. The paper contributes to the existing literature on activist translation by analysing a data set that combines linguistic choices and qualitative data collected by observation and interviews. It relates the translational choices in the subtitles with the stories these groups tell about themselves. The narratives mediated in the subtitles suggest that both liminoid experiences share their choice of creativity and amateurism to challenge the extremist rigid discourse of ISIS. Similarly, the choice of silencing the Islamic register in the subtitles feeds into the common aim shared by the two groups to disconnect the fundamentalist thoughts and doctrines of ISIS from Islam. Yet, DT and BDS have distinct positionings in relation to their socio-political surroundings which are reflected in the different translation modes deployed. DT, which is more national oriented, tended to foreignise the cultural-bound terms, while BDS, which is more cosmopolitan, tended to naturalise them. It is perceived also that the online medium was key in the development of English and French subtitles in both initiatives. Since DT did not include subtitles from the start, while BDS included only English, posting these videos online stirred user conversation on the need to add subtitles to the videos in English and French.

The paper discussed the role of activist translation as part of the online transfer and production of knowledge cross-culturally. Yet, other areas still need further research like the role of automated caption tools or technology in general in providing or facilitating activist translation. Moreover, one of the major challenges of examining such fluid production of knowledge is that it is, in itself, ephemeral, as digital content is easily changed, erased, censored or blocked. Additionally, as a means of self-protection from serious consequences, most of the agents choose to remain anonymous, making it difficult to identify their origins, social or cultural belongings as well as backgrounds.

Acknowledgment

This paper is the fruit of the author’s participation in a three-year research project that was organised by the German Institute Leibniz Center for the Modern Orient (ZMO). During her participation in the project, the author worked under the supervision of Prof. Randa Abou Bakr, Cairo University. The research project focused on two sociological concepts: liminality and knowledge production. The author’s contribution discussed the applicability of both concepts to activist translation practices, exemplifying such by scrutinizing the subtitling of counter-extremist videos produced by Daya alTaseh and The Bigh daddy Show post-Arab Spring.

References

Al-Mohammad, H. (2020). Tracing the online translations of Syrian “Poetry of Witness”: 2011-2016 [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Ottawa. https://ruor.uottawa.ca/server/api/core/bitstreams/31cd1523-3603-4fb6-87e7-3deb540f57d0/content

Baker, M. (2006a). Translation and conflict. Routledge.

Baker, M. (2006b). Translation and activism: Emerging patterns of narrative community. The Massachusetts Review, 47(3), 462-484.

Baker, M. (2007). Reframing conflict in translation. Social Semiotics, 17(2), 151-169.

Baker, M. (2013). Translation as an alternative space for political action. Social Movement Studies, 12(1), 23-47.

Baker, M. (2014). Translation as re-narration. In J. House (Ed.) Translation: A multidisciplinary approach (pp. 158-177). Palgrave Macmillan.

Baker, M. (Ed.) (2015). Translating dissent: Voices from and with the Egyptian revolution. Routledge.

BBC Arabic (2016, March 7). ""ذا بيغ دادي شو" صفحة على فيسبوك تسخر من تنظيم "الدولة الإسلامية ‘The Bigh Daddy Show: Facebook page that makes fun of ISIS’. https://www.bbc.com/arabic/multimedia/2016/03/160307_digital_big_daddy

BDS (Aʿmaq al-Khalifah Barhoom) @bighdaddyshow. (n.d.). About [Facebook channel]. Facebook. Retrieved January 29, 2018 from https://web.facebook.com/bighdaddyshow/about/?ref=page_internal

BDS (The Bigh daddy Show). (n.d.). About [YouTube channel]. YouTube. Retrieved January 29, 2018 from https://www.YouTube.com/channel/UCtGjdrpcakgWdfAYKd2b4aw/about

BDS (The Bigh daddy Show). (n.d.). Playlists [YouTube channel]. YouTube. Retrieved January 29, 2018 from https://www.youtube.com/@thebighdaddyshow9707/playlists

BDS (The Bigh daddy Show). (n.d.). Videos [YouTube channel]. YouTube. Retrieved January 29, 2018 from https://www.youtube.com/@thebighdaddyshow9707/videos

BDS (The Bigh daddy Show). (2016, March 25). The Caliphate quizz [Video]. YouTube. Retrieved January 29, 2018 from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vQJF0fQBk-s

Boéri, J. (2008). A narrative account of the Babels vs. Naumann controversy: Competing perspectives on activism in conference interpreting. The Translator, 14(1), 21-50.

Bruner, J. (1991). The narrative construction of reality. Critical Inquiry, 18(1), The University of Chicago Press, 1-21.

Conway, K. (2019). Cultural translation. In M. Baker, & G. Saldanha (Eds.) Routledge encyclopedia of translation studies (3rd ed., pp. 129-133). Routledge.

D’hulst, L., & Gambier, Y. (Eds.) (2018). A history of modern translation knowledge: Sources, concepts, effects. John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/btl.142

Díaz-Cintas, J. (2018). 'Subtitling's a carnival': New practices in cyberspace. The Journal of Specialised Translation, (30), 127-149.

Domat, P. C. (2016, November 21). « Le Bigh Daddy Show » : ce dessin animé ridiculise le groupe Etat islamique ‘The Bigh Daddy Show: this cartoon ridicules the Islamic State’, Rue89. https://www.nouvelobs.com/rue89/rue89-monde/20160927.RUE3911/le-bigh-daddy-show-ce-dessin-anime-ridiculise-le-groupe-etat-islamique.html

DT (Daya.Altaseh @DayaAltaseh.Media). (n.d.). About [Facebook channel]. Facebook. Retrieved February 19, 2018 from https://web.facebook.com/DayaAltaseh.Media/about/?ref=page_internal

DT (Dāyʿat al-Tāsat). (n.d.) About [YouTube channel]. YouTube. Retrieved February 19, 2018 from https://www.youtube.com/c/DayaAltaseh/about

DT (Dāyʿat al-Tāsat). (n.d.) Sketches playlist [YouTube Channel]. YouTube. Retrieved February 19, 2018 from https://www.youtube.com/@DayaAltaseh/playlists/sketches

DT (Dāyʿat al-Tāsat). (n.d.) Videos [YouTube Channel]. YouTube. Retrieved February 19, 2018 from https://www.youtube.com/@DayaAltaseh/videos

DT (Dāyʿat al-Tāsat). (2015, June 1) ISIS Twitter [Video]. YouTube. Retrieved February 19, 2018 from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nLlN-Gsv7Zw

Harding, S. A. (2012). “How do I apply narrative theory?”: Socio-narrative theory in translation studies. Target. International Journal of Translation Studies, 24(2), 286-309.

Hermans, T. (2019). Descriptive translation studies. In M. Baker, & G. Saldanha (Eds.) Routledge encyclopedia of translation studies (3rd ed., pp. 143-147). Routledge.

Jones, H. (2019). Narrative. In M. Baker, & G. Saldanha (Eds.) Routledge encyclopedia of translation studies (3rd ed., pp. 356-361). Routledge.

Lieberman, A. V. (2017). Terrorism, the internet, and propaganda: A deadly combination. Journal of National Security Law & Policy, 9)95(, 95-124.

Mehrez, S. (Ed.) (2012). Translating Egypt's Revolution: The Language of Tahrir. The American University in Cairo Press.

Orrego-Carmona, D., & Lee, Y. (Eds.) (2017). Non-Professional subtitling. Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Pérez-González, L. (2010). Ad-hocracies of translation activism in the blogosphere: A genealogical case study. In M. Baker, M. Olohan, & M. C. Pérez (Eds.) Text and context: Essays on translation and interpreting in honour of Ian Mason (pp. 259-287). St. Jerome.

Pérez-González, L. (2012). Translation, interpreting and the genealogy of conflict. Journal of Language and Politics, 11(2), 169-184.

Pérez-González, L. (2017). Investigating digitally born amateur subtitling agencies in the context of popular culture. In D. Orrego-Carmona & Y. Lee. (Eds.) Non-Professional subtitling (pp. 15-36). Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Pérez-González, L., & Susam-Saraeva, Ş. (2012). Non-Professionals translating and interpreting: Participatory and engaged perspectives. The Translator, 18(2), 149-65.

Selim, S. (2016). Text and context: Translating in a state of emergency. In M. Baker (Ed.) Translating dissent: Voices from and with the Egyptian revolution (pp. 77-87). Routledge.

Somers, M. R., & Gibson, G. D. (1993). Reclaiming the epistemological other: narrative and the social constitution of identity. CRSO Working Paper Series 499, The University of Michigan, 1-77.

St-Pierre, P., & Kar, P. C. (Eds.) (2007). In Translation – Reflections, refractions, transformations. John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/btl.71

Thomassen, B. (2009). The uses and meaning of liminality. International Political Anthropology, 2(1), 5-28.

Thomassen, B. (2012). Revisiting liminality: The danger of empty spaces. In Liminal landscapes: Remapping the field (pp. 21-35). Routledge.

Turner, V. (1974). Liminal to liminoid, in play, flow, and ritual: An essay in comparative symbology. Rice Institute Pamphlet - Rice University Studies, 60(3), 53-92.

Turner, V. (2002). Liminality and communitas. In M. Lambek (Red.) A reader in the anthropology of religion (pp. 358-374). Blackwell Publishers. (Original work published 1969).

Tymoczko, M. (2000). Translation and political engagement: Activism, social change and the role of translation in geopolitical shifts. The Translator, 6(1), 23-47.

Tymoczko, M. (2010a). Ideology and the position of the translator. In M. Baker (Ed.) Critical readings in translation studies (pp. 213-228). Routledge.

Tymoczko, M. (2010b). Translation, resistance, activism. University of Massachusetts Press.

Tymoczko, M., & Gentzler, E. (Eds.) (2002). Translation and power. University of Massachusetts Press.

United Pixels (n.d.). Higgledy Piggledy ضايعة الطاسة. https://unitedpixels.media/portfolio/higgledy-piggledy/

Venuti, L. (1995). The translator's invisibility. Routledge.

Wright, R., Berger, J. M., Braniff, W., Bunzel, C., Byman, D., Cafarella, J., Gambhir, H., Gartenstein-Ross, D., Hassan, H., Lister, C., McCants, W., Nada, G., Olidort, J., Thurston, A., Watts, C., Wehrey, F., Whiteside, C., Wood, G., Zelin, A. Y., & Zimmerman, K. (2016). The jihadi threat ISIS, al-Qaeda, and beyond. United States Institute of Peace. Retrieved from https://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/The-Jihadi-Threat-ISIS-Al-Qaeda-and-Beyond.pdf

Zekraoui, L. (2017). The politics of translating the Arab Spring: translation as an agency to contest authoritarianism in MENA: A critical introduction (Publication No. 10282262) [Doctoral dissertation, State University of New York at Binghamton]. ProQuest. https://www.proquest.com/docview/1934410666

Data Availability Statement

The author confirms that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article [and/or its supplementary materials].

Disclaimer

The author is responsible for obtaining permission to use any copyrighted material contained in their article and/or verify whether they may claim fair use.

ORCID 0009-0005-2188-9595; e-mail mennaahmed2008@gmail.com↩︎

Expression usually said by Muslims whenever they are intending or going to do something.↩︎

In Islamic law, mahram connotes a state of consanguinity precluding marriage.↩︎

Notes

See English publications of ISIS main media arm al-Hayat Media.↩︎