Constitution is not identity: On equivalence relations in translation of performance and translation for performance

Sarah Maitland1, Queen’s University Belfast

ABSTRACT

In the race to secure the sub-rights to Amanda Gorman’s ground-breaking performance at the 2021 United States presidential inauguration, a high-profile case emerged in which the translator appointed by Dutch publisher Meulenhoff returned the commission, following criticism of the appointment. Building on the detailed critical interrogations of structural and racial inequity that were published in response to the ensuring controversy, this article delineates additional perspectives, by asking what is instructional in the debate on the who of translating Gorman’s performance, when it comes to other instances of translation of performance, and how we may learn from it in other contexts of translation for performance. Using performance as a concretising lens, or “system of meaning” (Pavis, 1992) that takes on significance only in the coming together of the relationships united in production and reception (p. 25), and through the application of theories of mathematical equivalence relations, this article questions what the controversy tells us about what translation of performance ‘is’ and ‘should’ be, and suggests what lessons might be learned with regard to the notion of equivalence in translation.

KEYWORDS

Equivalence; category theory; Leibniz’s Law; translation for performance; theatre translation.

1. Introduction

By the time this article is published, the winner of the 2024 United States presidential election will have been inaugurated. One of the highlights (Bykowicz, 2021) of the inauguration some four years ago was undoubtedly when National Youth Laureate Amanda Gorman performed her spoken word poem ‘The hill we climb’. In the race to secure the sub-rights to internationalise her ground-breaking performance for global readerships, a high-profile case emerged in which the translator appointed by Dutch publisher Meulenhoff returned the commission, following criticism of the appointment. The translator in question was International Booker prize-winning writer Marieke Lucas Rijneveld, and when a piece by journalist Janice Deul was published in De Volkskrant on 25 February 2021 describing Meulenhoff’s choice as “incomprehensible” (Kotze, 2021b) — Deul contrasted Gorman’s work and life “coloured by her experiences and identity as [a] [B]lack woman” with Meulenhoff’s choice of translator, who Deul described as “white, non-binary, [and with] no experience [in spoken word performance translation]” (2021b) — Rijneveld stood down the next day (Rijneveld, 2021). In the ensuing public debate, commentators pinpointed the “scarcity of Black translators and other translators of colo[u]r, a scarcity caused by long-term patterns of discrimination in education and publishing” (ALTA, 2021) and the “urgent need for more openness and opportunities in publishing, more visibility of translators of colour and more proactive intervention to help dismantle the institutional barriers faced by early career translators” (Society of Authors, 2021). The “essential element of unknowingness that animates the translator’s curiosity and challenges her intellectual mettle and ethical responsibility” was raised (Chakraborty, 2021), alongside concerns that the case risked the possibility of a world “where the validity of one’s experience and ideas is contingent on identity” (Braden, 2021). “Even when translators hail from — or belong to — the same culture as the original author”, it was noted, “the art [of translation] relies on the oppositional traction of difference” (Chakraborty, 2021).

Before proceeding, it is worth emphasising that this article will not duplicate the detailed critical interrogations of structural and racial inequity published in response to the controversy. Kotze (2021a) notes:

Deul’s question is why, for this particular text, in this particular context, given its significance, Meulenhoff chose not to opt for a young, [B]lack, female, spoken-word artist. Joe Biden’s choice of Gorman as reader of her own poem at his inauguration created a particular configuration of cultural value around precisely these qualities. Gorman’s visibility, as a young [B]lack woman, matters: She is part of the message. The choice of translator, in this case, is similarly part of the message. It’s about the opportunity, the space for visibility created by the act of translation, and who gets to occupy that space.

In Kotze’s terms, an opportunity was missed “to carry the importance of this visibility into the Dutch cultural space by giving a [B]lack translator the same ‘podium’ Gorman represents” (2021a). As Kotze and Strowe (2021) argue, critical attention must be drawn to the allocation, distribution and recognition of translation tasks, and to which “social, economic, political, and institutional forces and agents are involved in choosing who will translate” (p. 352). The question arises of who is permitted to represent the work of another, since “structurally, institutionally, and politically, the translation and interpreting industry lacks representativeness” (p. 352). The issue, as Choi, Evans and Kim (2021) observe, “is about translation being a site for the colonised or marginalised to make their voices heard” (p. 355). What is needed, Susam-Saraeva argues, is the infrastructure to support translators and the state-level interventions to achieve more permanent and immediate results, as well as diversity and representativeness across the full range of actors involved (2021, p. 360).

Nor does this article address the question of who has the right to translate. As the ALTA ‘Statement on racial equality in literary translation’ (2021) recognises, “the question of whether identity should be the deciding factor in who is allowed to translate whom is a false framing of the issues in play”. Having the same or similar background, Susam-Saraeva argues, “does not guarantee that stories will be told respectfully” (2021, p. 362), and, as Inghilleri adds, “a shared common history, language, culture, gender or country of origin cannot incontrovertibly be equated with shared experiential knowledge, nor can experiential knowledge be reduced to such commonalities” (2021, p. 98). For the Society of Authors, ethical responsibility is about due regard for “transparency, accountability and inclusivity in publishing processes”, and looking beyond word-of-mouth recommendations in favour of “hiring diverse editorial staff, and freelance translators and editors” (2021). To do so, is to invite reflection over and above the individual, on what Inghilleri terms the level “of the shared burden” (2001, p. 98).

If the direction of travel has so far rightly been concerned with questioning where representational power lies in the literary translation appointments process and with drawing critical attention to whom the opportunity to represent has been granted hitherto, then what this article will do is interrogate the what and the how: what is instructional in this debate on the who of translating Gorman’s performance, when it comes to other instances of translation of performance, and how may we learn from it in other contexts of translation for performance? Using performance as a concretising lens, or “system of meaning” (Pavis, 1992) that takes on significance only in the coming together of the relationships united in production and reception (p. 25), this article will examine what it means to read the Meulenhoff controversy not through the prism of literary translation but of performance translation. By asking what other tools we have at our disposal for articulating the translation challenges that inhere — namely, theories of mathematical relations — this article questions what the controversy tells us about what translation of performance ‘is’ and ‘should’ be.

The logic of mathematical relations is used to address an important what that is borne of the paradox at the heart of the controversy. In her critique, Deul sets up a comparison between Gorman and Meulenhoff’s appointed translator (Kotze, 2021b). This comparison creates a distinction between the former, whose characterisation is grounded in her education (“Harvard alumna Gorman”), childhood (“raised by a single mother”) and ethnicity (“her work and life are coloured by her experiences and identity as [a] [B]lack woman”), and the latter, who is characterised along lines of ethnicity, gender identity, and experience: “[W]hite, non-binary, [and with] no experience [in spoken word performance translation]”. Following Deul’s piece, and Rijneveld’s demission, it was reported that the publisher Univers had dropped their Catalan translator because, the translator claimed, he was “not the right person” for the role (AFP, 2021). “It is a very complicated subject that cannot be treated with frivolity”, he was reported as saying,

[b]ut if I cannot translate a poet because she is a woman, young, [B]lack, an American of the 21st century, neither can I translate Homer because I am not a Greek of the eighth century BC. [Nor] could [I] have translated Shakespeare because I am not a 16th-century Englishman” (2021).

The logical extension of this argument appears to be that the only acceptable translation would be Gorman’s own, since the only person a performer can be the same as is herself. Yet, Kotze’s reading of Deul’s piece offers an alternative view. Given the gravity of Gorman’s performance and what is represented by her platform, “[i]n choosing Rijneveld as translator”, Kotze writes, “the publisher missed an opportunity to carry the importance of this visibility into the Dutch cultural space by giving a [B]lack translator the same ‘podium’ as Gorman represents” (2021a). By this logic, it is not ‘sameness of translator’ that underscores an acceptable translation but ‘sameness of representational platform’ — a platform which permits each stakeholder to be different, while seeking sameness of context, which is defined in terms of opportunity to be visible against the backdrop of cultural significance evident in Gorman’s performance.

What is at stake in the conceptualisation of performance translation in these two opposing arguments? In the former, the translator must be identical to the author of the performance-for-translation, so that the translation equates favourably to the performance if, and only if performer and translator are one and the same. Mathematically, this would mean that there would not be two stakeholders, but one. In the latter conceptualisation, by contrast, a translator is not required to be identical to the author in order for an equivalence of platform to be shared, thus allowing for two different stakeholders to be involved. But how can the two entities brought together in this translational equation be different, if what they share is the same? It is to the task of accounting for this difference that this article sets itself.

2. Constitution is not identity

The principle of the identity of indiscernibles holds that that if two things share all the same properties, then they are identical; similarly, the principle of the indiscernibility of identicals holds that if two things are identical, then they share all the same properties (Ladyman and Bigaj, 2010). Together, these form what is commonly referred to as Leibniz’s Law (Rodriguez-Pereyra, 2012). It follows from Leibniz’s Law that if two things share all the same properties, then they are not in fact two in number but one. Another way of saying this is that no two things can be exactly the same and numerically different, since the one self-same thing cannot be two (Rodriguez-Pereyra, 2012).

Through symbolic notation, we can simplify these complex ideas (Forrest, 2010) by combining recognisable symbols with the verbal logic of Leibniz’s Law. Given that Leibniz’s Law is all about which things have what properties, we can give each thing a name, let’s say ‘x’ and ‘y’, and we can employ the most common symbolic notation for ‘property’, ‘F’. The indiscernibility of identicals (1) and the identity of indiscernibles (2) can now be written as:

For every x and every y, if x is identical to y, then every F that is possessed by x is also possessed by y, and every F that is possessed by y is also possessed by x.

For every x and every y, if every F that is possessed by x is also possessed by y, and every F that is possessed by y is also possessed by x, then x is identical to y (after The Power of Language: Philosophy and Society, 2013).

Let us turn to a performance context. The front page of the programme for Brigid Larmour’s production of The merchant of Venice at the RSC (Trafalgar Theatre Productions, et. al, 2024) bears an image of Tracy-Ann Oberman, who plays Shylock. In the background, a poster on a brick wall. Across four lines of text, the words “William Shakespeare’s/ The Merchant/ of Venice/ Directed by Brigid Larmour” (2024). Daubed over the poster in red paint, the year “1936”. Shakespeare’s presence is invoked through the possessive noun identifying him as the figure in whom ownership of the performance is recognised. In the language of the programme, therefore, the play which was performed before the court of King James in 1605 (Royal Shakespeare Company, n.d.) and the play identified in the programme as “Shakespeare’s” are indiscernible. Through the possessive noun, they are not two numerically different plays, but the one self-identical ‘Merchant’. We might infer that the same principle applies to the playtext republished in the First Folio of 1623, which also opens with a possessive noun: “Mr. William Shakespeares [sic] comedies, histories, & tragedies” (Victoria and Albert Museum, 2017). The logic of Leibniz’s Law appears to hold, but only for the property of authorship, for if they do not share all the same properties, then the various ‘Merchants’ (the 1605 performance; the 1623 First Folio; and Larmour’s 2024 production) are different. And yet, somehow, we know that they are not disparate things; the challenge is to name and explain the relation that succeeds in uniting them.

In a mathematical equivalence relation, which we can call R, the elements that are related to one another — which we can call a, b and c — are equivalent if and only if the relation of their properties is reflexive, symmetric and transitive (Fleck, 2017, pp. 69–73). A relation is reflexive when every element relates to itself, and is noted symbolically as: aRa. Thus, we can say that Shakespeare is the same as no one else except himself. The relation is symmetric when for every pair of elements, for example, a and b, if a relates to b, then b must relate to a. This is noted symbolically as aRb and bRa. The relation is transitive when for every trio of elements, for example, a, b and c, if a is related to b and if b is related to c, then a must also be related to c. This is noted symbolically as aRc (Rosen, 2007 and Anderson, 2004). Imagine now that the relational property in question is people’s birthdays (Cheng, 2023), and that person a is Shakespeare. Since a is the same person as himself, a must have the same birthday as a, making the relation between a and a reflexive, or: aRa. If person b was also born on 26 April (Shakespeare’s date of baptism — we do not know his date of birth), then the relation between a and b is symmetric, since they both share the same property, or: aRb and bRa. If person c shares the same birthday as b, and if b shares the same birthday as a, and if a was born on 26 April, then we can deduce that c was also born on 26 April, since the relation between all three is transitive, and that which is true for one is true for all, or: if aRb and bRa, and if bRc, then aRc. If we apply this to the case of the many ‘Merchants’, and if the property in question is one of authorship, then all three — the 1605 performance, which we can call ‘a’; the 1623 First Folio, ‘b’; and the 2024 RSC production, ‘c’ — are relationally equivalent, since, authorially, what is true for one is true for all. Where this logic comes apart, however, is the fact that not everything holds true for all, and, under Leibniz’s Law, if they share different properties, then they cannot be the ‘same’.

As with Gorman’s own ground-breaking performance, Larmour’s production was acclaimed (Akbar, 2023) for the way in which it crafts intentionally a representational platform against a particular sociocultural and historical context. By locating it at a time when Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists was poised to march through the Jewish East End of London, the production enables Oberman’s Shylock to take on fresh significance with respect to previous portrayals. This was the first time the role had been played by a woman, and, in Larmour’s production, Shylock is reimagined as a Cable Street business owner, single mother and survivor of antisemitic attacks. Against the real-world historical backdrop of antisemitism and political and social unrest in east London, performance decisions ranging from projections of contemporary newsreels tracking the rise of fascism and its antisemitic declarations, the actors’ gestures (including arm salutes and spitting at Shylock’s feet), the daubing of graffiti on the walls of Shylock’s home, and a strategic evolution in costume (Bassiano starts out dressed in gentleman’s leisure wear, and ends the play wearing a black uniform and red armband, evocative of Mosley’s ‘Blackshirts’), come together to form the production’s “system of meaning” (Pavis, 1992) through which Shylock’s demand for flesh can be viewed differently. As one review argues, this demand:

seems less driven by simple vengeance and more an outraged response to Mosley’s campaign of antisemitic persecution — as well as a single mother’s fearful defence against the rising forces conspiring to render her powerless. ‘If you prick us, do we not bleed?’ sounds like a plea not only for tolerance but for sanity against the fascist madness around her (Akbar, 2023).

It is problematic to base our concepts of equivalence on intrinsic qualities alone, for while all three ‘Merchants’ share the same author, Larmour’s production could not distinguish itself more from the play’s history. This problem of intrinsic qualities is illustrated in a logic puzzle beloved of ancient philosophers (Wasserman, 2021). Let us suppose that on Monday, an artist purchases an unformed lump of clay which we will call Lump. On Tuesday, the artist sculps Lump into a statue, and names it Venus de Milo (2021). If both are composed of the same clay and each has exactly the same mass, then for as long as Lump entirely constitutes Venus de Milo and Venus de Milo is entirely constituted by Lump, we can say that both are identical and indiscernible, since, intrinsically speaking, they appear to be exactly alike. It is useful to recall our earlier symbolic expression of Leibniz’s Law. Here, instead of ‘x’ and ‘y’, we can use the notations ‘l’ and ‘v’ to represent Lump and Venus de Milo:

For every l and for every v, if l is identical to v, then every F that is possessed by l is also possessed by v, and every F that is possessed by v is also possessed by l.

For every l and for every v, if every F that is possessed by l is also possessed by v, and every F that is possessed by v is also possessed by l, then l is identical to v.

Let us suppose that on Wednesday the artist becomes frustrated and dissolves v in some sort of solvent which destroys all trace of the statue and the clay which constituted it. Since neither v nor l could survive the change, “a natural thing to say is that the careers of the statue and the lump or piece of clay which made it up are entirely coincident” (Johnston, 1992, p. 89). From this perspective, v simply ‘is’ l, and vice versa, and their identicalness can be expressed through the equal sign (=), as in l=v and v=l. Despite this tempting identification, however, the two differ in many respects (Wasserman, 2021). What if, on Thursday, the artist resolves to squash v in a fit of pique? While l could survive the squashing, since it remains the same lump of clay as itself, v could not, since it would no longer be a statue. A property thus holds of l which does not hold of v: that of being able to survive being squashed (Johnston, 1992, p. 89). Suppose that the artist elects neither to dissolve nor to squash the statue, and by Friday, v’s arms instead become lost. It would continue to be known as Venus de Milo, despite its missing arms. But now a property holds of v which does not hold of l: that of being able to survive the loss of material parts (p. 97). We can conclude that even though v is constituted by l throughout its career, “the statue is not identical with the clay, since the statue could have survived certain changes which the piece of clay could not have survived” (p. 89). How, then, do we account for the fact that, for the first half of the week, l and v appear to be identical and indiscernible, while on Thursday and Friday the same objects are now different?

An analogous performance case is that of the National Theatre and Playful Productions co-production of The house of Bernarda Alba, directed by Rebecca Frecknall and based on a playtext by Alice Birch, “after Federico García Lorca” (National Theatre, n.d.). The “after” concerns what Pavis (1992, p. 24) describes as the “dramatic text” — that is, “the verbal script which is read or heard in performance” — which was written by Birch but based on my literal translation of Lorca’s Spanish original which was commissioned by Playful Productions. Underlying the mise en scène, which is the “confrontation of all signifying systems, in particular the utterance of the dramatic text in performance”, and which exists only when received and reconstructed by a spectator (Pavis, 1992, p. 25), there are two texts: my literal translation, which we can call a, and Birch’s dramatic text based on my translation, b. While it is right that translators of theatrical literals are recognised, credited and remunerated for the part they play in the mise en scène, it is also fully expected that the material constitutions of a dramatic text and the literal on which it is based are manifestly different, such that all the properties of one do not hold for the other. Among the many distinguishing features of Birch’s dramatic text with respect to my literal, was, in the words of one review, “the surprising amount of swearing” (Curtis, 2023). “I’m no prude”, the reviewer writes, “but it does seem discordant that women in a house governed by rectitude and decorum should give quite so many f***s, as it were, in conversation with each other” (2023). And yet, the non-identity of a and b, as it were, is entirely the point of translation for performance. Performance is the newness borne of distinguishing features with respect to what has gone before, together with the opportunity for renewed thinking that a fresh approach activates. Dramatically, the careers of a and b were never intended to be coincident; they are not the same, and it is not a shame for us to say so. Returning to l and v, the answer to the puzzle is that while they are constituted of the same thing, the objects must never have been identical, for if they had been, then their careers would not have been coincident on Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday and uncoincident on Thursday and Friday. Johnston (1992, p. 97) argues that intrinsic qualitative similarity represents an “unreliable road to identity”. Simply because two things are constituted from the same intrinsic substance, we might say, does not make them qualitatively the same.

3. Leibniz’s Law and the Gorman-Meulenhoff corpus

We can trace these problematics of equivalence relations in the Meulenhoff controversy. Recalling Leibniz’s Law, if two things share all the same properties, then they must be the same; in order for them to be the same, then they must share all of the same properties. In De Volkskrant, Deul writes:

Nothing to the detriment of Rijneveld’s qualities, but why not choose for a writer who — just like Gorman — is a spoken word artist, young, female, and: unapologetically Black? We are captivated by Amanda Gorman — and for good reason — but we are blind to the spoken word talent in our own country. Not to be found, you say? I can share a few names from my personal network. A list that is therefore nowhere near complete: Munganyende Hélène Christelle, Rachel Rumai, Zaïre Krieger, Rellie Telg, Lisette MaNeza, Babs Gons, Sanguilla Vabrie, Alida Aurora, Pelumi Adejumo. All talents who enrich the literary landscape, and who often fight many years for recognition. What would it be like to let one of them take on the task? Wouldn’t that make Gorman’s message more powerful? (Kotze 2021b; emphasis added).

The first sentence identifies four properties relating to vocation/occupation, generation, gender and race, and an imagined “writer who”, who holds all the same properties. Through the simile “just like Gorman”, the imagined writer holds the same properties as Gorman herself (“a spoken word artist, young, female, and: unapologetically Black”). Symbolic notation is again instructional here, since, numerically, the text identifies two writers: Gorman herself, who we can call ‘g’, and the imagined writer, who we can call ‘w’. In the logic of the text, both g and w hold the same properties, such that what is true of g is true of w and what is true of w is true of g. Under Leibniz’s Law, this would mean that g and w are identical and indiscernible, such that the work they produce — the performance and its translation — would be the same work. But there is a third person to be considered. Deul continues:

Is it then — to put it most mildly — not a missed opportunity to commission Marieke Lucas Rijneveld for this job? They are white, non-binary, have no experience in this area, but yet are, according to Meulenhoff, the ‘dream translator’? (Kotze, 2021b).

Here, an explicit tripartite comparison is made between the properties ascribed to Gorman, g; the imagined writer who holds the same properties, w; and those of Meulenhoff’s chosen translator, who we can call ‘m’. Recall the insight that a set of elements is relationally equivalent if and only if the relation of their properties is said to be reflexive, symmetric and transitive, such that whatever is true for one is true for all. Using once again the equal sign (=) to denote identicalness, and now the slashed equal sign (≠) to denote non-identicalness, we might say that in the language of Deul’s statement, while g=w and w=g, since m≠g and m≠w, then g, w and m are not relationally equivalent.

This lack of relational equivalence is evident in the press coverage surrounding the Meulenhoff controversy. Nexis is an online archive of over 40,000 premium and web news outlets (LexisNexis, n.d.). A search of all Nexis-indexed newspapers, newswires and press releases was performed against the keywords ‘Meulenhoff’ and ‘Gorman’, between 20 January 2021, the date of Gorman’s performance, and 20 December 2023, the census date for this study, yielding 35 distinct results, published in English. Where two versions of the same article were found, the older was excluded. The resulting corpus is catalogued in table 1:

| Date | Publisher |

|---|---|

2/4/21 2/3/21 |

Agence France Presse — English (2021a)

|

| 17/3/21 | Arutz Sheva (Meotti, 2021) |

| 26/2/21 | The Associated Press (AP News Wire, 2021) |

16/4/21 2/4/21 30/3/21 20/3/21 11/3/21 8/3/21 4/3/21 3/3/21 |

CE Noticias Financieras English (2021a)

|

| 12/3/21 | CNN Wire (Guy, 2021) |

| 11/3/21 | The Conversation (Chakraborty, 2021) |

27/2/21 12/3/21 |

The Daily Telegraph (Our Foreign Staff, 2021)

|

| 3/3/21 | Deutsche Welle Arts and Culture (2021) |

6/3/21 13/3/21 |

Die Welt (English) (Delius, 2021)

|

| 1/3/21 | EUR/Electronic Urban Report (MaGee, 2021) |

| 2/3/21 | Gates of Vienna (Bodissey, 2021) |

6/3/21 1/3/21 7/3/21 |

The Guardian (Flood, 2021a)

|

| 26/2/21 | The Independent (Michallon, 2021) |

| 2/3/21 | MailOnline (AfpMegan Sheets for dailymail.com, 2021) |

31/3/21 29/3/21 26/3/21 |

The New York Times (Daniels, 2021)

|

| 28/2/21 | Simple Justice (SHG, 2021) |

| 3/4/21 | South China Morning Post (Lyons, 2021) |

| 21/5/23 | telegraph.co.uk (Arbuthnot, 2021) |

| 31/3/21 | Thai News Service (2021) |

| 27/2/21 | The Times (Moody, 2021) |

| 28/3/21 | The Toronto Star (Pineda, 2021) |

Table 1. Gorman-Meulenhoff corpus: By publisher.

193 instances were identified in which a particular property had been ascribed to Gorman. These 193 property ascriptions were coded into a total of 10 property ascription groupings, outlined in table 2:

| Property (Frequency) | Exemplar | Publisher |

|---|---|---|

| Vocation/occupation/career achievement (62) | “US youth poet laureate Amanda Gorman […]” | Thai News Service (2021) |

| “[…] the youngest inaugural poet in US history” | The Daily Telegraph (Our Foreign Staff, 2021) | |

| “[…] the young American Black author Amanda Gorman […]” | Gates of Vienna (Bodissey, 2021) | |

| Race/ethnicity (52) | “[…] the [B]lack American poet Amanda Gorman” | telegraph.co.uk (Arbuthnot, 2021) |

| “[…] the work of the African-American poet” | CE Noticias Financieras English (2021d) | |

| Age (38) | “[…] the young [B]lack star of President Joe Biden’s inauguration […]” |

MailOnline (AfpMegan Sheets for dailymail.com, 2021) |

| Gender (15) | “[…] criticism that a [W]hite author was selected to translate the words of a Black woman […]” | Simple Justice (SHG, 2021) |

| Nationality (11) | “[…] chosen to translate American poet Amanda Gorman’s work into Dutch […]” | The Associated Press (AP News Wire, 2021) |

| Celebrity (11) | “[…] Gorman read […] in January to widespread acclaim” | The Independent (Michallon, 2021) |

| Education (1) | “[…] a Harvard graduate like Gorman” | South China Morning Post (Lyons, 2021) |

| Ability (1) | “[…] Gorman, […] is crazy talented […]” | — (Lyons, 2021) |

| Professional representation (1) | “[…] and is surrounded by heavyweight image makers like IMG Models” | — (Lyons, 2021) |

| Fashion sense (1) | “[…] a [B]lack, young, cool woman in Prada […]” | Die Welt (English) (Delius, 2021) |

Table 2. Gorman-Meulenhoff corpus: Property ascription groupings, by frequency.

In the property ascription grouping ‘Vocation/occupation/career achievement’, authors described Gorman variously as:

a “poet” (33 instances)

an “inaugural poet” (8 instances)

a “poet laureate” (8 instances)

a “writer” (6 instances)

an “author” (3 instances)

an “artist” (1 instance)

a “spoken-word [performer]” (1 instance)

a “performer” (1 instance)

an “activist” (1 instance)

In the grouping ‘Race/ethnicity’, 45 instances were identified in which authors described Gorman as “Black” and 7 in which she is identified as “African-American”.

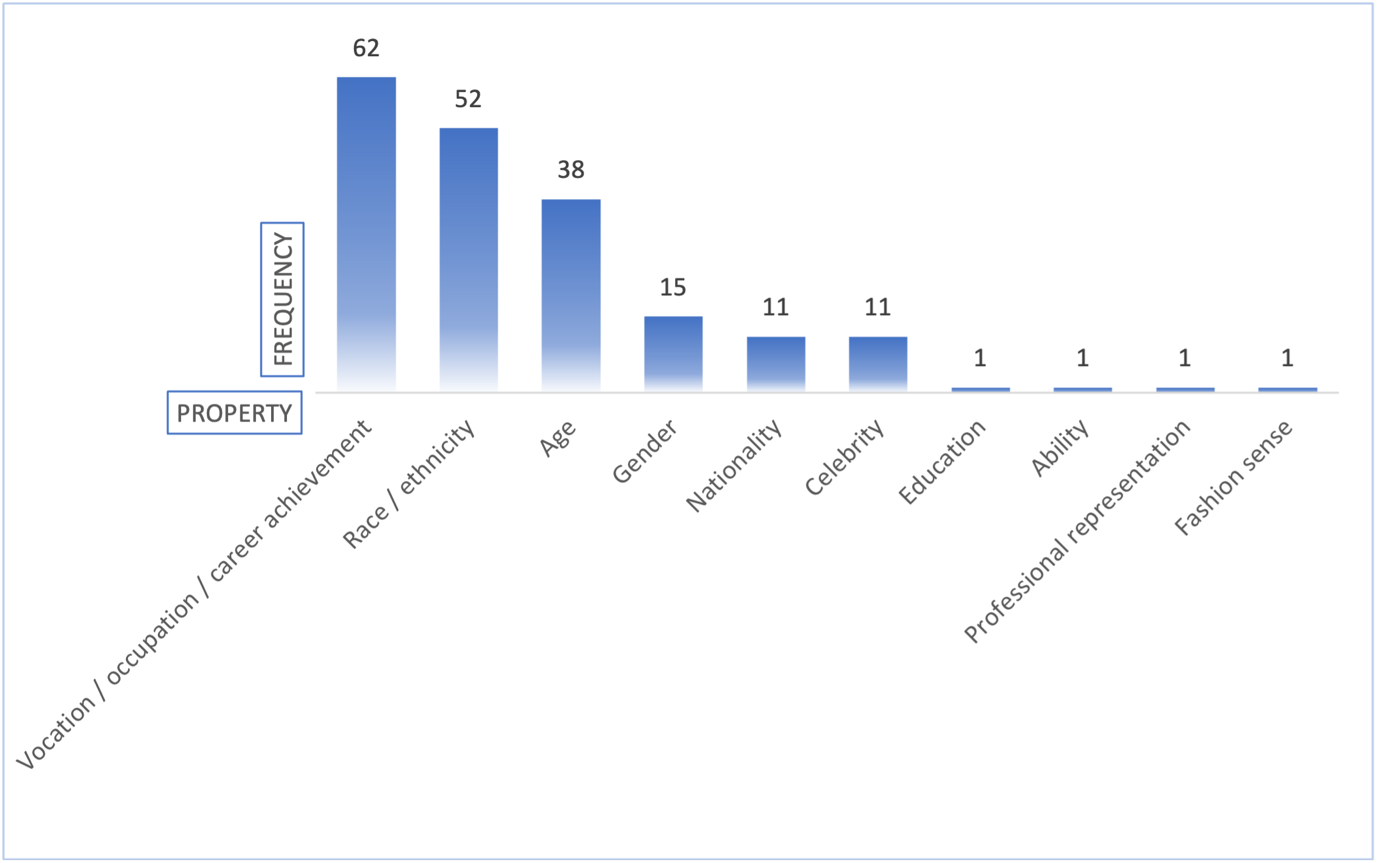

With regard to frequency, the overall picture is illuminating:

Figure 1. Gorman-Meulenhoff corpus: Frequency of property ascription

groupings.

As figure 1 shows, the predominance of ascriptions is clustered around what the authors perceive to be Gorman’s vocation/occupation/career achievement; her race/ethnicity; and her age. Their frequency is suggestive both of the relative significance attached, and of their bearing on any implicit or explicit comparison with Meulenhoff’s choice of translator.

As signalled in the Introduction, a range of interventions have addressed the inequities of opportunity affecting global majority writers and translators and the lack of representativeness at a structural level. The application of Leibniz’s Law to the Gorman-Meulenhoff corpus appears to delineate an additional perspective. It follows from Leibniz’s Law that:

(1), x=y if and only if for any property x has, y also has, and for any property y has, x also has, and—

(2), if x and y have different properties, then x≠y and y≠x.

Since the controversy hinges on an imbalance of properties, Meulenhoff’s choice of translator with respect to translating Gorman’s performance for global readerships could not fulfil Leibniz’s Law since, in the language of the texts analysed in the corpus, all the properties ascribed to one are not shared by the other. It is here where the next puzzle emerges, because the ‘identity’ denoted by the equal sign in x=y categorises x and y as ‘one and the same thing’, which is to say, that they are qualitatively identical and numerically identical because they share the same properties, and hence, that they are not two distinct things but one, sharing all the same properties while being called by different names.

A similar logic is at work in, say, the International Booker prize, which is awarded annually “for the finest single work of fiction from around the world which has been translated into English and published in the UK and Ireland” (Booker Prizes n.d.a, emphasis added). In 2023, the work (Time shelter) identified explicitly as being “the” winner (n.d.a), is further identified as being “by Georgi Gospodinov, translated by Angela Rodel”. Two names are in use, and we are told that the £50,000 prize money is divided equally “between the author and translator” (Booker Prizes, n.d.b). But, from the perspective of awarding the “winner”, there is only one work identified in the logic of the prize: Time shelter. In the unique worldview of the prize, we might say, the work written by Gospodinov in Bulgarian and the work written in English translation by Rodel are numerically and qualitatively identical. And yet, even at the level of the consumer, there is clearly a difference between the book one might purchase as Времеубежище, published by Janet 45, and the book one might purchase as Time shelter, published by Weidenfeld and Nicolson. Numerically, they are two, and qualitatively, among many other things, one is in Bulgarian and the other in English.

With respect to Gorman’s performance, we must start by saying that no book-of-the-performance could be identical to the performance itself, since the former takes place in a live setting of spectatorship, and the latter inscribes into writing the words of the performance for the benefit of readers. As a signifying system, the mise en scène takes on meaning only in the coming together of the network of relationships united in production and reception (Pavis, 1992, p. 25). Everything about the context of Gorman’s performance contributes to the eventness of her mise en scène, from the grandeur of the inauguration ceremony and its stage design to the historical, political, and sociocultural backdrop against which Gorman’s performance stands in relief. When the text inscribing her performance is translated into Dutch, we can further say that even at a basic interlingual level, because one is in English and the other is in Dutch, the two cannot be identical. Indeed, the only numerically and qualitatively equal relation that emerges from the Meulenhoff controversy is that of Gorman to herself. Regardless of who is appointed to translate her performance, all translations will be numerically and qualitatively distinct, and hence unequal to her performance.

By what logic, then, can we account for the relation that obtains between text and translation, when the two are numerically and qualitatively distinct, and thus unequal?

4. What are we counting as the same?

Reformulated, the foregoing question asks: can two different things ever be the same? The musical West side story, by Jerome Robbins, lyrics by Stephen Sondheim, book by Arthur Laurents, music by Leonard Bernstein and performed at the Winter Garden Theatre on Broadway on 26 September 1957 (Library of Congress, n.d.), is numerically and qualitatively unequal to William Shakespeare’s The tragedie of Romeo and Juliet, thought to be first performed exactly four hundred years earlier (Zarevich, 2023). If we call West side story ‘x’ and The tragedie of Romeo and Juliet ‘y’, we can express their non-identicalness symbolically as follows:

x≠y

We can also say that the actor Bradley Cooper — let’s call him b — is the same person as himself (that is, b=b) and we can say that Cooper is not the same person as the composer Leonard Bernstein — let’s call him a — despite the former playing the latter in the film Maestro (Cooper, 2023). Since a and b are numerically and qualitatively unequal, while it is true that Bernstein is Bernstein and Cooper is Copper, and Cooper is playing Bernstein in a film about Bernstein’s life, Bernstein and Cooper are clearly not the same person. We can express this non-identicality symbolically as:

a=a and b=b, but—

b≠a

But that is not the end of the relational story. Because it is possible to make connections between even different things (Cheng, 2024, p. 16), and despite the sense that these things are manifestly not the same, there may be a sense in which they are equivalent. The term ‘equivalent’ is distinct from the term ‘equal’; the former expressing a connection between non-identicals, and the latter expressing numerical and qualitative identity. Any such connection between non-identicals is not an essence, and is not based on intrinsic characteristics — recall that material constitution is a problematic route to identity — but on wider contextual categories, which is to say, on deliberate choices to evaluate them under one or other category (p. 19).

Category theory is interested in evaluating connections between different things, and, as a unifying theory, it can “simultaneously encompass a broad range of topics and also a broad range of scales by zooming in and out” (p. 16). One of its starting points in this act of “zooming” is the importance of “studying things in context rather than in isolation” (p. 16). It takes the view that what bears importance in a given context “is the ways in which things are related to one another, not their intrinsic characteristics” (p. 17). If the category in question is the figure of Leonard Bernstein — his life and career, not the human being who lived until 1990 — then the figure portrayed by Cooper in the film Maestro is not ‘different’ per se, since both the actor and his on-screen portrayal are playing the same role, in the sense that from the perspective of the viewer, the figure on screen ‘is’ that of Bernstein, even though the embodiment is clearly Cooper’s and not Bernstein’s. The two remain different, but in a cinematic context there is a sense in which they are the same. Similarly, Larmour’s Merchant of Venice 1936 is not numerically and qualitatively identical to Rupert Gould’s 2011 production, which is set in a Las Vegas casino, yet their shared Shakespearean connection is no less real, just as my literal translation of La casa de Bernarda Alba, and Birch’s dramatic text performed as The house of Bernarda Alba remain different and yet they are inextricably linked.

This sense of sameness within difference is present in Oberman’s portrayal of Shylock. “What always bothered me”, she says in an interview, “is that Shylock says ‘I am content’ [after the trial] and you never see her again. In our production, you absolutely see her again” (Jays, 2023). Elsewhere she says that “[i]t has been a lifelong cherished dream of mine to bring this play to the stage in a new way, reimagining Shylock as one of the tough, no-nonsense Jewish matriarchs I grew up around” (Rook, 2023). While there is a transitive sense in which the various ‘Merchants’ are relationally equivalent (from the perspective that the Shylock inscribed in the First Folio of 1623 is the ‘same’ Shylock as the Shylock portrayed by Patrick Stewart in Gould’s 2011 production, and Oberman in Larmour’s 2024 production), there is also thus an important sense in which they are different. This is evidenced in the ambitions of Larmour’s production, which sought to “frame the problematically antisemitic characters of Portia, Antonio and Gratiano as British fascists of that time”, with Oberman’s portrayal aimed explicitly at “reclaiming” (Jays, 2023) the character from its history.

Since translation is in the business of creating comparables between things which are simultaneously non-identical and yet related, translation implies both a rupture and a continuity (Lillebø, 2014). Bearing in mind that one of the primary objectives of category theory is to find “more nuanced ways of describing sameness” (Cheng, 2024, p. 18), we can view equivalence as a more flexible notion than equality, because it permits us to make a choice — against or within a given context — as to which things we want to count as the same, and which things we want to count as different, so as to achieve a particular point of view on them. While it is possible to consider objects on their own, as a series of same objects, this approach is not very revealing, since to define sameness is to outline difference and then to exclude it, or, as Lillebø observes, “[t]he problem with sameness is that it is oppositional, and hence closed” (2014, p. 1).

It is only when we bring things into comparison, by placing them in a category, that we start to consider the relationships between them. In other words, by “identifying and articulating similarities between different situations, and then finding a unified way to think about them” (Cheng, 2023), we can construct a unique vantage point from which to study the relationships that inhere. By constructing comparables we bring disparate things into the category of the same, and by inviting comparison, we bring them into relation. Context matters because things change character depending on what context they are in (Cheng, 2024, p. 16); it all comes down to what is “counted as the same” (Cheng, 2023).

What might it mean to read the Meulenhoff controversy through the lens of category theory? A concordance analysis of the Gorman-Meulenhoff corpus reveals that of the 18 occurrences of the term ‘same’, in a third of cases (6), the nouns that are modified point to Gorman and the properties ascribed to her:

| Publisher | Property | Nouns modified | Collocation |

|---|---|---|---|

CE Noticias Financieras English (2021h) |

Race/ethnicity | “skin color” | “Only a person of the same skin color as Gorman, who is 22 years old, could properly translate the poems this young woman has written, they believe.” |

| “‘We want to learn from this by dialogue,’ justified the publisher, who is already looking for new candidates to translate Amanda’s poems into the Dutch language ‘as best as possible and in the same spirit,’ that is, with the same skin color.” | |||

| — (2021d) | Race/ethnicity | “skin color” | “For this reason, he criticized the publisher for not choosing a translator with the same skin color as Gorman, a ‘young artist, woman and, without a doubt, Black’.” |

| “Spanish writer Victor Obiols was vetoed for not having the same skin color as Amanda Gorman.” | |||

The Conversation (Chakraborty, 2021) |

Race/ethnicity | “culture” | “Even when translators hail from — or belong to — the same culture as the original author, the art relies on the oppositional traction of difference.” |

| Nationality | |||

Die Welt (Delius, 2021) |

Age | “generation” | “[…] “The Hill We Climb,” […], will not be translated into Dutch by Marieke Lucas Rijneveld, even though Gorman had even argued for the International Booker Prize winner Rijneveld as her translator, who is herself a poet — both belong to roughly the same generation [sic] Gorman was born in 1998, Rijneveld in 1991.” |

Table 3. Gorman-Meulenhoff corpus: ‘Same’ and its collocations, by publisher.

This contrasts with Deul’s piece, where the term ‘same’ does not appear once in Kotze’s translation. In the light of category theory, Deul’s term, “like”, takes on a new dimension: “Nothing to the detriment of Rijneveld’s qualities, but why not choose for a writer who — just like Gorman — is a spoken word artist, young, female, and: unapologetically Black?” (Kotze, 2021b; emphasis added). Implicit in this quality of likeness is an alsoness — someone else who is also a spoken word artist, also young, etc. Also, but not the same as. This person is not Gorman, but they do share certain properties, which, in the language of category theory, are the things which are counted as the same. Equivalent, we might say, but permitted (through the things which are counted as different) not to be identical.

5. Conclusions

As Kotze (2021a) argues, Deul “highlights the mismatch between the shared lived experiences of the [B]lack Gorman and the [W]hite Rijneveld, and the lack of experience of Rijneveld (in respect of translation) […]”. Given that Gorman’s work and life are influenced so strongly by her lived experience as an African American woman, a historically, culturally, and politically relevant opportunity was missed to commission a translation from spoken word performers at the local level who have been hitherto underrepresented in the literary system. It is not so much a “mismatch” in backgrounds that creates the problem, Kotze writes, but the fact that “Gorman’s visibility, as a young [B]lack woman, matters” (2021a). To the extent that the message cannot be separated from its sender, “the choice of translator, in this case, is similarly part of the message. It’s about the opportunity, the space for visibility created by the act of translation, and who gets to occupy that space” (2021a). What is ‘counted as the same’ here are not categories of race, ethnicity, gender, or age on their own (which, taken out of historical, cultural and political context, do not tell us much except that the properties ascribed to a given translator b are not equal those ascribed to a given author a), but the specific historically, culturally, and politically relevant contexts of “genres that have traditionally not been included in the canon”, and of Black, women, spoken word performers who have been, in Deul’s words, “only marginally represented in the literary system” (Kotze, 2021b).

What we might count as ‘different’ is the category of experiential knowledge, which is to permit that the experience of one person need not map onto that of another, and thus, that the ‘right’ to translate (Susam-Saraeva, 2021) need not hinge on lived experience alone. What is counted as the same is the category of opportunity, set against a backdrop of discrimination, inequity and marginalisation of people and the work they produce. The categorical translation this approach suggests would allow for what Pavis describes as the “crossing of ways, of traditions, of artistic practices”, where distinctiveness does not melt away or become subsumed to some universal substance (1992, p. 6), and where “the final and only guarantors of the culture which reaches them, whether it be foreign or familiar” is the spectator. If mise en scène seeks to provide a dramatic text with a situation that gives meaning to the statements of the text (p. 30), then it is not so much with Gorman’s performance that we seek connection, but with the meanings to which her performance gives rise, in a context of historical, political, and sociocultural relevance. It is towards an equivalence of meaning in context, that translations of such a performance might most meaningfully be orientated.

References

AFP. (2021, March 10). ‘Not suitable’: Catalan translator for Amanda Gorman poem removed. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2021/mar/10/not-suitable-catalan-translator-for-amanda-gorman-poem-removed

Agence France Presse — English. (2021a, April 2). European publishers agonise over profile of Amanda Gorman translators. Agence France Presse — English. https://advance-lexis-com.gold.idm.oclc.org/api/document?collection=news&id=urn:contentItem:62BR-3JB1-JBV1-X2G5-00000-00&context=1519360

—. (2021b, March 2). Amanda Gorman’s white Dutch translator quits over ‘uproar’. Agence France Presse — English. https://advance-lexis-com.gold.idm.oclc.org/api/document?collection=news&id=urn:contentItem:6244-Y491-JBV1-X2FS-00000-00&context=1519360

AfpMegan Sheets for dailymail.com. (2021, March 2). International Booker Prize winner RESIGNS from assignment to translate work of Black inaugural poet Amanda Gorman into Dutch after ‘uproar’ because they’re white. MailOnline. https://advance-lexis-com.gold.idm.oclc.org/api/document?collection=news&id=urn:contentItem:6245-YSG1-JBNF-W3YN-00000-00&context=1519360

Akbar, A. (2023, March 2). The merchant of Venice 1936 review — Shylock takes on Oswald Mosley’s Blackshirts. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2023/mar/02/the-merchant-of-venice-1936-review-watford-palace-theatre

ALTA. (2021). ALTA statement on racial equity in literary translation. https://literarytranslators.wordpress.com/2021/03/22/alta-statement-on-racial-equity-in-literary-translation/

Anderson, J. A. (2004). Discrete mathematics with combinatorics. Pearson Prentice Hall.

Arbuthnot, L. (2021, May 21). Céline, Hitler and the mafia — why translators are refusing to censor ‘dangerous’ texts. telegraph.co.uk. https://advance-lexis-com.gold.idm.oclc.org/api/document?collection=news&id=urn:contentItem:688W-1601-DY4H-K3MF-00000-00&context=1519360

AP News Wire. (2021, February 26). Dutch poet declines assignment to translate Gorman’s works. The Associated Press. https://advance-lexis-com.gold.idm.oclc.org/api/document?collection=news&id=urn:contentItem:6239-RN31-JBNF-W537-00000-00&context=1519360

Bodissey, B. (2021, March 2). Gates of Vienna News Feed 3/1/2021. Gates of Vienna. https://advance-lexis-com.gold.idm.oclc.org/api/document?collection=news&id=urn:contentItem:6244-R8B1-JCMN-Y1XG-00000-00&context=1519360

Booker Prizes. (n.d.a). The International Booker prize. https://thebookerprizes.com/the-international-booker-prize

Booker Prizes. (n.d.b). The International Booker prize and its history. https://thebookerprizes.com/international-booker-prize/the-international-booker-prize-and-its-history

Braden, A. (2021). Translators weigh in on the Amanda Gorman controversy. Asymptote. https://www.asymptotejournal.com/blog/2021/03/17/translators-weigh-in-on-the-amanda-gorman-controversy/

Bykowicz, J. (2021, January 20). Poet Amanda Gorman has star turn reading ‘The hill we climb’ at Biden inauguration. The Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/poet-amanda-gorman-has-star-turn-at-biden-inauguration-11611170398

Chakraborty, M. N. (2021). Friday essay: Is this the end of translation? The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/friday-essay-is-this-the-end-of-translation-156375

CE Noticias Financieras English. (2021h, March 3). Marieke Lucas, the white writer who has had to give up translating African-American Gorman. CE Noticias Financieras English. https://advance-lexis-com.gold.idm.oclc.org/api/document?collection=news&id=urn:contentItem:624J-83B1-JBJN-M0DD-00000-00&context=1519360

CE Noticias Financieras English (2021g, March 4). The hill we climbed. CE Noticias Financieras English. https://advance-lexis-com.gold.idm.oclc.org/api/document?collection=news&id=urn:contentItem:624S-7C11-DY1R-B0X9-00000-00&context=1519360

CE Noticias Financieras English (2021f, March 8). Because of his skin color (white) they prevented him from translating the poem of Biden’s assumption; now justifies the decision. CE Noticias Financieras English. https://advance-lexis-com.gold.idm.oclc.org/api/document?collection=news&id=urn:contentItem:625M-43J1-DY1R-B3NF-00000-00&context=1519360

CE Noticias Financieras English (2021e, March 11). Who can translate Amanda Gorman? CE Noticias Financieras English. https://advance-lexis-com.gold.idm.oclc.org/api/document?collection=news&id=urn:contentItem:6268-1K91-JBJN-M3VD-00000-00&context=1519360

CE Noticias Financieras English (2021d, March 20). Black poet Amanda Gorman’s translators are criticised for being white. CE Noticias Financieras English. https://advance-lexis-com.gold.idm.oclc.org/api/document?collection=news&id=urn:contentItem:6286-2VV1-DY1R-B29C-00000-00&context=1519360

CE Noticias Financieras English (2021c, March 30). Amanda Gorman, Biden’s poet, sparks debates about speaking place among translators. CE Noticias Financieras English. https://advance-lexis-com.gold.idm.oclc.org/api/document?collection=news&id=urn:contentItem:62B9-9HS1-JBJN-M3BW-00000-00&context=1519360

CE Noticias Financieras English (2021b, April 2). Who should translate Amanda Gorman? The debate shakes the publishing world in Europe. CE Noticias Financieras English. https://advance-lexis-com.gold.idm.oclc.org/api/document?collection=news&id=urn:contentItem:62BY-6JG1-DY1R-B1J4-00000-00&context=1519360

CE Noticias Financieras English (2021a, April 16). Amanda Gorman: translate with correction... politics. CE Noticias Financieras English. https://advance-lexis-com.gold.idm.oclc.org/api/document?collection=news&id=urn:contentItem:62FX-TC41-DY1R-B3N8-00000-00&context=1519360

Cheng, E. (2024). The joy of abstraction: An exploration of math, category theory, and life. Cambridge University Press.

Cheng, E. (2023). Interview with Eugenia Cheng. Interviewed by Steven Strogatz for The Joy of Why. https://www.quantamagazine.org/is-there-math-beyond-the-equal-sign-20230322/

Choi, J., Evans, J. and Kim, K. H. (2021). Response by Choi, Evans and Kim to ‘Representing experiential knowledge’. Translation Studies, 14(3), 354–358. https://doi.org/10.1080/14781700.2021.1971109

Cooper, B. (Director). (2023). Maestro [Film]. Lea Pictures, Sikelia Productions, Amblin Entertainment and Fred Berner Films.

Our Foreign Staff. (2021, February 27). Author turns down Black poet translation. The Daily Telegraph. https://advance-lexis-com.gold.idm.oclc.org/api/document?collection=news&id=urn:contentItem:623F-RJ91-JCBW-N43F-00000-00&context=1519360

Daniels, N. (2021, March 31). Should white writers translate a Black author’s work?; student opinion. The New York Times. https://advance-lexis-com.gold.idm.oclc.org/api/document?collection=news&id=urn:contentItem:62B9-8HY1-JBG3-650P-00000-00&context=1519360

Delius, M. (2021, March 6). The paradox of experience: can a poem by a Black author only be translated by a Black translator? On a current paradigm shift. Die Welt (English). https://advance-lexis-com.gold.idm.oclc.org/api/document?collection=news&id=urn:contentItem:624Y-H6R1-DY2B-S28P-00000-00&context=1519360

Fleck, M. M. (2017). Building blocks for theoretical computer science. Margaret M. Fleck. https://mfleck.cs.illinois.edu/building-blocks/index-sp2020.html

Flood, A. (2021a, March 6). Marieke Lucas Rijneveld writes poem about Amanda Gorman furore. The Guardian. https://advance-lexis-com.gold.idm.oclc.org/api/document?collection=news&id=urn:contentItem:624Y-NNH1-JBNF-W4TS-00000-00&context=1519360

Flood, A. (2021b, March 1). ‘Shocked by the uproar’: Amanda Gorman’s white translator quits. The Guardian. https://advance-lexis-com.gold.idm.oclc.org/api/document?collection=news&id=urn:contentItem:623Y-0P41-DY4H-K3MV-00000-00&context=1519360

Forrest, P. (2010, July 31). The identity of indiscernibles. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/identity-indiscernible/

Guy, J. (2021, March 12). A translator for Amanda Gorman’s poem has been dropped in Spain. CNN Wire. https://advance-lexis-com.gold.idm.oclc.org/api/document?collection=news&id=urn:contentItem:6268-4271-DY7V-G3BJ-00000-00&context=1519360

Inghilleri, M. (2021). Response by Inghilleri to ‘Representing experiential knowledge’. Translation Studies, 14(3), 95–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/14781700.2020.1848617

Jays, D. (2023, February 22). ‘Is it antisemitic? Yes’: How Jewish actors and directors tackle The merchant of Venice. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2023/mar/02/the-merchant-of-venice-1936-review-watford-palace-theatre

Johnston, M. (1992). Constitution is not identity. Mind, 101(401), 89–105. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2254121

Kotze, H. (2021a). Translation is the canary in the coalmine. Medium. https://haidee-kotze.medium.com/translation-is-the-canary-in-the-coalmine-c11c75a97660

Kotze, H. (2021b). English translation: Janice Deul’s opinion piece about Gorman/Rijneveld. Medium. https://haidee-kotze.medium.com/english-translation-janice-deuls-opinion-piece-about-gorman-rijneveld-8165a8ef4767

Kotze, H. and Strowe, A. (2021). Response by Kotze and Strowe to ‘Representing experiential knowledge’. Translation Studies, 14(3), 350–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/14781700.2021.1972039

Ladyman, J. and Bigaj, T. (2010). The principle of the identity of indiscernibles and quantum mechanics. Philosophy of Science Association, 77(1), 117–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/14781700.2021.1971109

LexisNexis. (n.d.). What is Nexis? https://www.lexisnexis.co.uk/products/nexis.html

Library of Congress. (n.d.). West side story: Birth of a classic. https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/westsidestory/westsidestory-exhibit.html

Lillebø, J. G. (2014). Translation as critique of ‘cultural sameness’. Ricoeur, Luther and the practice of translation. Nordicum-Mediterraneum, 9(1).

Lyons. S. J. (2021, April 3). US poet’s works risk being lost in translation. South China Morning Post. https://advance-lexis-com.gold.idm.oclc.org/api/document?collection=news&id=urn:contentItem:62CK-2DK1-DYRW-R4D8-00000-00&context=1519360

MaGee, N. (2021, March 1). White poet pulls out of translating Amanda Gorman’s inauguration poem amid criticism. EUR/Electronic Urban Report. https://advance-lexis-com.gold.idm.oclc.org/api/document?collection=news&id=urn:contentItem:6243-CS91-JCMN-Y1X8-00000-00&context=1519360

Malik, K. (2021, March 7). Lost in translation: The dead end of dividing the world on identity lines. The Guardian. https://advance-lexis-com.gold.idm.oclc.org/api/document?collection=news&id=urn:contentItem:6256-MSY1-DY4H-K2RN-00000-00&context=1519360

Marshall, A. (2021a, March 29). Lost in translation: A poem’s hopes for unity. The New York Times. https://advance-lexis-com.gold.idm.oclc.org/api/document?collection=news&id=urn:contentItem:629W-1KY1-DXY4-X461-00000-00&context=1519360

Marshall, A. (2021b, March 26). Amanda Gorman’s poetry united critics. It’s dividing translators. The New York Times. https://advance-lexis-com.gold.idm.oclc.org/api/document?collection=news&id=urn:contentItem:6298-SKK1-DXY4-X1FB-00000-00&context=1519360

Meotti, G. (2021, March 17). Western progressives now burn books. Arutz Sheva. https://advance-lexis-com.gold.idm.oclc.org/api/document?collection=news&id=urn:contentItem:627C-TCV1-JDJN-6444-00000-00&context=1519360

Michallon, C. (2021, February 26). Dutch writer Marieke Lucas Rijneveld steps down from assignment to translate Amanda Gorman’s work. The Independent. https://advance-lexis-com.gold.idm.oclc.org/api/document?collection=news&id=urn:contentItem:623B-JTH1-JBNF-W1JW-00000-00&context=1519360

Moody, O. (2021, February 27). I won’t translate Black poet’s work, insists white author. The Times. https://advance-lexis-com.gold.idm.oclc.org/api/document?collection=news&id=urn:contentItem:623F-RJB1-JCBW-N1FF-00000-00&context=1519360

National Theatre. (n.d.). The house of Bernarda Alba. https://www.nationaltheatre.org.uk/productions/the-house-of-bernarda-alba/

Deutsche Welle Arts and Culture. (2021, March 3). Amanda Gorman’s Dutch translator steps down. Deutsche Welle Arts and Culture. https://advance-lexis-com.gold.idm.oclc.org/api/document?collection=news&id=urn:contentItem:624D-1MJ1-F03R-N551-00000-00&context=1519360

Pavis, P. (1992). Theatre at the crossroads of culture (L. Kruger, Trans.) Routledge.

Pineda, D. (2021, March 28). When diversity gets lost in translation; Activists want publishers to consider identity when hiring literary translators. The Toronto Star. https://advance-lexis-com.gold.idm.oclc.org/api/document?collection=news&id=urn:contentItem:629N-WN91-F197-53DW-00000-00&context=1519360

The Power of Language: Philosophy and Society. (2013). Leibniz’s law. https://philosophyreaders.blogspot.com/2013/01/leibnizs-law.html

Rijneveld, M. L. [@Lucas_Rijneveld]. (2021, February 26). Bij dezen laat ik weten dat ik heb besloten de opdracht om het werk van Amanda Gorman te vertalen terug te geven. [Tweet]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/Lucas_Rijneveld/status/1365293135996325895

Rodriguez-Pereyra, G. (2012). Leibniz’s argument for the identity of indiscernibles in his letter to Casati (with transcription and translation). The Leibniz Review, 22, 137–150.

Rook, O. (2023). The merchant of Venice 1936 to transfer to the West End, starring Tracy-Ann Oberman. London Theatre. https://www.londontheatre.co.uk/theatre-news/news/merchant-of-venice-1936-transfers-to-west-end-starring-tracy-ann-oberman

Rosen, K. (2007). Discrete mathematics and its applications. McGraw-Hill.

Royal Shakespeare Company. (n.d.). Stage history. https://www.rsc.org.uk/the-merchant-of-venice/about-the-play/stage-history

SHG. (2021, February 28). Words of a different color. Simple Justice. https://advance-lexis-com.gold.idm.oclc.org/api/document?collection=news&id=urn:contentItem:623S-2751-F03R-N2HC-00000-00&context=1519360

Society of Authors. (2021). Time for racial equality in literary translation. https://societyofauthors.org/News/News/2021/April/Time-for-racial-equality-in-literary-translation

Susam-Saraeva, Ş. (2021). Representing experiential knowledge: Who may translate whom? Translation Studies, 14(3), 84–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/14781700.2020.1846606

Thai News Service. (2021, March 31). World: Amanda Gorman’s inauguration poem appears in German. Thai News Service. https://advance-lexis-com.gold.idm.oclc.org/api/document?collection=news&id=urn:contentItem:62B4-WBJ1-JB5P-J1SX-00000-00&context=1519360

Trafalgar Theatre Productions and Eilene Davidson Productions, in association with the Royal Shakespeare Company (2024, February 3) William Shakespeare’s The merchant of Venice 1936 directed by Brigid Larmour [Event programme]. The Swan Theatre, Stratford-Upon-Avon.

Victoria and Albert Museum. (2017). Shakespeare’s First Folio. https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O1397689/shakespeares-first-folio-book-shakespeare-william/

Wasserman, R. (2021). Material constitution. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/material-constitution/

Whelan, E. (2021, March 12). This latest literary row is a threat to creativity; Amanda Gorman’s translator needs to know how to interpret her work, not share her identity, argues Ella Whelan. The Daily Telegraph. https://advance-lexis-com.gold.idm.oclc.org/api/document?collection=news&id=urn:contentItem:6267-BNJ1-DYTY-C3FK-00000-00&context=1519360

Yücel, D. (2021b, March 13). Only for people of color; Following the discussion about the translation of Amanda Gorman’s poem “The hill we climb”, another translator has now had his contract withdrawn. About the absurd idea of making the translation of literature dependent on the translator’s skin colour. Die Welt (English). https://advance-lexis-com.gold.idm.oclc.org/api/document?collection=news&id=urn:contentItem:626F-9MN1-JBK9-20GF-00000-00&context=1519360

Zarevich, E. (2023). Her bounty is boundless. JSTOR Daily. https://daily.jstor.org/her-bounty-is-boundless/

Data availability statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to copyright restrictions, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Disclaimer

The authors are responsible for obtaining permission to use any copyrighted material contained in their article and/or verify whether they may claim fair use.

ORCID 0000-0002-2024-8359, e-mail: info@sarahmaitland.co.uk↩︎