The implications of new censorship theory: Conformity and resistance of subtitle translators in China

Lu Yan1, University of Geneva

ABSTRACT

Censorship penetrates the decisions made about multilingual communication in an age defined by technification, digitisation and ‘Internetisation’. Rather than perceiving censorship solely as a repressive action externally exerted on subjects, this article explores its productive nature in the hands of new censorship theory in both official and non-official contexts. At its outset, the article presents the Chinese government’s legal control over the media landscape, casting a shadow over the subtitling industry’s present policies. It then examines three self-censorship practices of subtitle translators, based on in-depth interviews and questionnaires conducted with professional and non-professional subtitle translators in state media, media localisation companies and fan-subtitling teams. Subtitle translators, under the impact of explicit and implicit regulations imposed by state actors and structural mechanisms of control, either conform to or circumvent and challenge these regulations. Productive censorship can shape the knowledge and opinions, foster extensive discussions, inspire innovative translation strategies, create fresh lexicons, and enhance the marketability of audiovisual products to a wider audience.

KEYWORDS

Censorship, new censorship theory, productive, subtitling, professional and amateur, China.

1. Introduction

Censorship is a pervasive occurrence that exists in all countries and throughout history, but with variations (Kuhiwczak, 2009; Mercks, 2007). The fear of diminishing authority through the exposure of “speech, book, play, film, state secret or whatever” (Green, 2005, p. xviii), compels authoritative censors to interfere with the process of free communication, and impose detrimental and coercive sanctions for non-compliance and dangerous thoughts. Censorship intervenes in the realm of individuals’ voluntary actions within civil society (Cohen & Arato, 1992) and possesses the ability to “block, manipulate, and control cross-cultural interaction in various ways” (Billiani, 2020, p. 56) in translation. Therefore, ongoing scholarly analysis portrays censorship as repressive interventions by political authorities, which distort and bias the original material in audiovisual translation (Alfaro de Carvalho, 2012; Díaz Cintas, 2019; Gutiérrez Lanza, 2002; Izwaini, 2015, 2017; Khoshsaligheh & Ameri, 2016; Mereu, 2012).

Postmodern critics critique the traditional concept of censorship, in which the censor is externally placed upon the censored, due to its repressive and authoritative nature. The proliferation of global trade and international communications in the process of neo liberalisation has loosened the government’s formal role, making the influence of hidden kinds of social and cultural control more noticeable in the postmodern present. As Merkle observed, “the covert censorship at work in the free democracies of late modernity characterised by expanding globalisation, though at times more difficult to detect, is nonetheless, at times insidiously, pervasive” (2002, p. 10). Instead of acting as external and repressive forces, the various forms of censorial power might unexpectedly stimulate a substantial surge in conversations and debates, foster new discourses and construct knowledge (see e.g., Foucault, 1976/1978; Gilbert, 2013; Loseff, 1984; Patterson, 1984; Simon, 2015). Hence, it is imperative to accept more contemporary approaches of censorship that defies the established boundaries of censorship.

Censorship, as conceived by new censorship theory, exercises control over all aspects of the audiovisual translation practices, either through direct and explicit legal acts by the state or through the invisible cultural and social impact of nonstate actors. The study initially presents the government’s legislative authority over the media landscape and casts a shadow over the current policies implemented in the subtitling industry. Based on in-depth interviews and questionnaires conducted with professional and non-professional subtitle translators in state media, media localisation companies and fan-subtitling teams, it subsequently examines how the ‘new censorship’ emanating from diffuse and decentred forms of power serves as a productive force in audiovisual translation within both official and non-official settings. It also discusses three self-censorship practices adopted by subtitle translators to either conform to or circumvent and challenge these regulations.

Censorship can be seen as a productive force that generates new discourses and constructs knowledge in both professional and non-professional contexts. The state media’s stated regulations, influenced by political ideologies, shape the knowledge and opinions of professional translators and the general public. Professional translators typically comply with censorship restrictions and faithfully convey prevailing discourses to the broader audience. Unlike professional translators, fansubbing translators are subject to quieter and more intangible forms of censorship, which are reinforced by cultural and social actors. These forms of censorship can provoke conversations and debates about sensitive topics, enhance the marketability of audiovisual products to a wider audience, motivate translators to develop more innovative and nuanced translation strategies, and generate unique translation styles, as well as introduce new vocabularies. Fansubbing translators adeptly circumvent and challenge censorship to magnify marginalised ideologies.

2. Methodology

An investigation was carried out to examine the subtitling workflow in professional and fan-based settings in China between June 2022 and October 2023. The study employed a combination of semi-structured interviews and questionnaires to gather data from 33 translators with a minimum of one year of expertise in subtitling. The participants were selected from one state media outlet, one media localisation company and two fan-subtitling teams. A total of 31 valid questionnaires were collected online from fan-subtitling Team A and B, consisting of 14 questionnaires from Team A and 17 questionnaires from Team B. At the time of questionnaire, the 31 participants had between one and five years of experience in subtitling. Table 1 displays the data collected from conducting interviews with four translators. The interviews were conducted using a combination of online and in-person approaches, lasting between 60 and 90 minutes at most. Two translators not only served as translators, but also played roles in establishing the organisations. With extensive experience, the two co-founders possess specialised expertise in evaluating subtitle translations and have a thorough comprehension of the subtitling industry as a whole.

| Translator | Experience at first Interview | Roles | Employment | Interview frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 5 years | Translator | State media | 2 online and in-person interviews |

| B | 11 years | Translator, Co-founder | Media localisation company | 1 in-person interview |

| C | 1 year | Translator | Fan-subtitling Team A | 1 online interview |

| D | 9 years | Translator, Co-founder | Fan-subtitling Team B | 6 in-person interviews |

Table 1. Translator interview data.

The questionnaires and interviews were conducted in a semi-structured manner. Upon the consent, the questions were customised based on the participant’s role as either a translator or a member of management. The questions posed to the translators primarily focused on their demographic characteristics, expertise in subtitling, the subtitling procedure, positions and duties, perspectives on the review procedure, strategies employed by translators in navigating censorship, and utilisation of machine translation. The purpose of these inquiries was to uncover the fundamental reasons of translators to either adhere to or challenge prevailing ideologies. The two co-founders received additional inquiries on the review procedure, potential interference with the work of translators, and the level of tolerance towards sensitive matters. The objective was to depict a comprehensive overview of the subtitling industry and to enhance comprehension of how censorship exerts varying affects at various organisational levels. The interviews and questionnaires were made anonymous. The respondents’ comments were somewhat altered to ensure the protection of their identities as well as the identities of the individuals or organisations they referred to.

3. China’s state legal control in the film industry

The audiovisual media are manipulated by the state to demonstrate prominent ideological attributes and bolster their political power. The consensus among Chinese authorities and academics is that the national image should be marketed through the media rather than solely relying on societal development or diplomatic promotion (Shambaugh, 2013, p. 168). The state exercises paramount authority in defining the prevailing ideology through film dissemination in China. The China Film Administration, under the Publicity Department of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China, holds the highest administrative power in the realm of film administration. In March 2018, it assumed the role that was formerly held by the State Administration of Radio, Film, and Television (SARFT). The government’s increased authority over the film industry is seen in this political move.

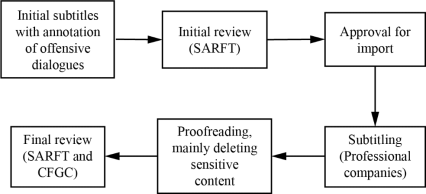

The authorities enforce pre-release censorship, or licensing and post-release censorship, on foreign films at every stage of the process, including importation, translation, and distribution. The government has enforced rigorous regulations to restrict the importation of foreign films and to foster and endorse domestic films. Foreign films must undergo pre-release censorship and obtain a licence before their release. The Regulations on the Administration of Movies (2001) stipulates that films must undergo review by the audiovisual authorities before importation and obtain a 电影片公映许可证 [‘Film public screening license’]. The Translation Bureau of the Import and Export Branch of China Film Group Corporation (CFGC) oversees the translation of foreign films (Jia & Qiao, 2004, p. 22). The Import and Export Branch of CFGC mandates that foreign films released in cinemas must be subtitled or dubbed by the four state studios including Shanghai Film Dubbing Studio, Changchun Film Dubbing Studio, Dubbing Studio of China Film Group Corporation and August First Film Studio (Entertainment Capital Theory, 2015). At present, there are four state-owned and private companies that specialise in subtitling imported films for public screenings: the Film Translation Company of Changchun Film Group Corporation, the Shanghai Film Translation Studio, Transn and Besteasy. In addition, foreign films can be dubbed and subtitled by the international division of China Central Television (CCTV from now on) at the CCTV Art and Literature Centre, and thereafter aired on CCTV 6 (CCTV movie channel) and CCTV 8 (CCTV TV Plays Channel). The formal protocols for importing foreign films are intricate and require a significant amount of time (Zhang, 2017). The prescribed protocol for subtitled foreign films is outlined as follows (Chen, 2014):

Figure 1. Official procedure for subtitled foreign films (author’s own; adapted from Chen, 2014).

According to Article 16 in the Provisional Regulations on Qualification Access for Film Enterprises (2004), the importation and distribution of films are solely overseen by film import companies that have received approval from the SARFT. In practice, the Import and Export Branch of CFGC is the sole film import business company designated by the SARFT. The Distribution and Exhibition Branch of CFGC and Huaxia Film Distribution Co., Ltd. jointly undertake the distribution of imported films (Liu, 2008).

Many other countries have clear and explicit censoring rules for films. The duration of a kissing scene is clearly stipulated in the Production Code, sometimes referred to as the Hays or Breen Code, for major Hollywood studios (Maltby, 1993). China’s rigorous cinema censorship is a result of the absence of a film rating system, which seeks to safeguard children from potentially dangerous content and enhance the options available to adults (Williams, 2015). In China, film censorship has been recognised as being notably “inconsistent, arbitrary, and unpredictable” and the policies tend to be written in purposefully vague and ambiguous language (Xiao, 2013, p. 125). The Film Industry Promotion Law (2016) is the inaugural legislation that governs the Chinese film industry and cultural sector (Wu, 2019, p. 160). The 10 restrictions on film content offer more detailed information compared to the previous restrictions outlined in the Regulations on the Administration of Movies (2001). Nevertheless, it maintains a certain level of uncertainty. Determining how to deal with offensive content for film subtitle translators has long been a challenging issue. The lack of clearly stipulated rules defining what constitutes ‘offensive’ for Chinese sensitivities, the constraints from Chinese linguistics, ideology, culture and cognition, and the potential risk of having a product banned by censors may encourage film translators to perform a very strict form of self-censorship. Professional subtitle translators often make their translations oblique by adopting drastic techniques like as deletion, substitution, generalisation, and omission when dealing with content that involves sex, violence, or politically and socially sensitive topics in films (Li, 2012; Wang, 2020; Zhang, 2004).

4. Implications of new censorship theory on China’s subtitle translation

The new approach to understanding censorship, termed ‘new censorship theory’ by Matthew Bunn (2015), has not gained prominence, as the liberal conception of censorship was widely accepted until the 1980s. Postmodern critics challenge the conventional understanding of censorship as an act “externally imposed upon a subject” (Butler, 1998, p. 247), overlooking “the very multiplicity and complexities of censorship” (Burt, 1993, p. 12). The contemporary conceptualisation of censorship, influenced by the work of Michel Foucault and Pierre Bourdieu, emphasises its diverse, ubiquitous, and constructive nature. It seeks to redefine the impact and manifestations of censorship and incorporate the concept of structural or constitutive forms of censorship. Censorship can be seen “broadly as a mechanism for legitimating and delegitimating access to discourse” (Burt, 1993, p. 12), existing among a dispersion of regulatory actors including governmental entities and diverse structural manifestations of power, such as “the market, deeply ingrained cultural norms, linguistic rules, and other impersonal limitations on acceptable communication” (Bunn, 2015, p. 27). Furthermore, censorship is both prohibitive and productive, as it “generates discourse as much as it inhibits it” (Gilbert, 2013, p. 4).

Subtitle translators are situated in wide-ranging networks of heterogeneous powers and control. These heterogeneous forms of censorship, reinforced by governmental, cultural, and social actors, might productively aid in the process of subtitle translation while simultaneously causing prohibitive effects. In the subsequent section, I delineate three self-censorship practices observed in both professional and amateur subtitle translators as they navigate complex forms of censorship, both within and beyond the scope of governmental regulation of audiovisual communications.

4.1. Internalising ‘political correctness’

In accordance with government regulations, the state media prioritise political correctness and actively promotes a positive national image to the audience. It has established specific procedures and guidelines to ensure adherence to these principles in translation. As an illustration, the translation guidelines in the state media incorporate explicit instructions for the translation of geographic names, highlighting the importance of thorough deliberation due to the political scrutiny criteria. The primary concerns are on China’s sovereignty, coupled by additional anxieties on the potential repercussions of bringing shame to China, as outlined below:

Use the Chinese Mainland, never Mainland China.

Use Taiwan, Taiwan Island or Taiwan Region.

Taiwan authorities, not Taiwan government officials.

Taiwan leader XXX or the leader of the Taiwan region, not Taiwan president

Whenever Taiwan, Hong Kong or Macao is involved in a group or collection of countries, use countries and regions.

WTO members, not WTO countries (as Macao, Hong Kong and Taiwan are also members).

APEC Informal Leadership Meeting or APEC Leaders Meeting — not APEC Summit or APEC Summit Meeting. APEC Financial Summit is acceptable since this only involves financial ministers.

On anniversaries involving Macao and Hong Kong — simply say the xth anniversary of their ‘return to China’. Not ‘return to Chinese sovereignty’, or ‘return to Chinese rule’. ‘Return to the Motherland’ is acceptable as a direct quote.

Hong Kong or Macao residents or compatriots — not Hong Kong or Macao citizens. (‘Compatriots’ is acceptable only if the person speaking is Chinese, which usually limits it to soundbites.)

Macao’s GAMING industry, not Macao’s gambling industry.

Normally use ‘overseas funded businesses/enterprises’ but not ‘foreign funded businesses/enterprises’, as much of the investment in the Chinese mainland comes from Hong Kong.

Use caution with foreign investors when related to the Chinese mainland. Use overseas investors when investment comes from Hong Kong, Macao and Taiwan.

In international sporting events, use the term Chinese Taipei team but not Taiwan team.

Translator A stated that the translations underwent the triple review process within the state media outlet where Translator A is employed:

Initially, foreign experts, either employed by the state media or external sources, scrutinise the translations. Subsequently, Chinese specialists affiliated with Xinhua News Agency, the leading media conglomerate in China, conduct a second round of evaluation. Finally, the translations undergo additional examination by higher-ranking individuals within the same department.

Translator B further explained that the state media employed Artificial Intelligence (AI) technology to detect sensitive content throughout the filtering process. However, translator B was unable to provide a specific catalogue of content censored by AI. It is noteworthy that Translator B’s media localisation company, although privately owned, is one of the outsourcing contractors providing audiovisual translation services for the state media. Translator B, a co-founder of this media localisation company, serves in a dual capacity as both a translator and a supervisor, internalising the policy, engaging in voluntary self-censorship and overseeing employees’ compliance. When speaking about the censorship policies in state media, translator B underscored the importance of engaging in meaningful discussions with specialists in state media regarding accurate translations: “for instance, in the phrase ‘the Yellow River floods’, the term ‘flood’ can be inaccurately rendered as 泛滥 [‘run rampant’] because of the revered status of the Yellow River as the mother river in Chinese culture”, emphasising a focus on accurate translation rather than censorship, removing himself from censorship questions. In addition to voluntary self-censorship, translator B must exercise involuntary self-censorship due to the arbitrary nature of the policy:

Despite my thorough examination of potential sensitivities, unforeseen sensitivities are occasionally flagged by censors. For instance, a former government official implicated in an audiovisual product broadcasted on a state-owned local TV channel led to the prohibition of subtitles and scenes featuring the official.

Furthermore, the interviews conducted with Translator A and B reveal the presence of dissent, which is affected by market factors. Both translators exhibit a minor disagreement over the translation policy from the audience’s standpoint:

Chinese specialists at Xinhua News Agency commonly utilise a careful and cautious approach in their translation work. Nevertheless, both I and foreign experts convey the notion that this approach presents challenges for viewers in comprehending the information completely (Translator A).

The potent “propaganda” included in audiovisual content leads to a decline in foreign audience engagement, resulting in a significantly low viewership rate in international markets (Translator B).

In official contexts, the two translators are required to adhere to ‘political correctness’ and are prohibited from any negative elements that could impact the state, as stated in the translation guidelines. The explicit act of censorship gradually forms their translation beliefs, which then become ingrained as an internalised ‘habitus’ (to use Bourdieu’s term). The translation beliefs structure translators’ everyday translation practices, influence their translation decisions, and foster their self-censorship practices. In the given instance of the Yellow River, the translator maintained the favourable portrayal of the Yellow River without specific regulations. Bourdieu articulates the concept of automatic censorship: “when each agent has nothing to say apart from what he is objectively authorised to say: in this case, he does not even have to be his own censor because he is, in a way, censored once and for all, through the forms of perception and expression that he has internalised and which impose their form on all his expressions” (1982/1991, p. 138). The official translators ultimately reproduce dominant discourses mandated by political ideologies, which impact a wider audience and facilitate their spread in the public sphere through the state media. Placing an undue emphasis on national interests and boundaries excessively prioritising national interests and boundaries might potentially undermine the interests of the audience, market advantages, and the precision of translations.

4.2. Enforcing market censorship

Bourdieu’s concept of censorship extends beyond the state as the exclusive agent, encompassing the use of euphemising in line with the established norms in the field where people communicate. Privatising cultural production transforms “commodification into an instrument of censorship” (Burt, 1994, p. Xi), which holds greater influence than state repressive censorship under neoliberalism: the inability to reproduce copyrighted audiovisual products online hinders the availability of free audiovisual communications; distributors selectively distribute audiovisual products considered ‘safe’, effectively censoring controversial or confrontational content that could potentially affect the number of views. This form of censorship, named “market censorship”, dependent on “anticipated profits and/or support for corporate values and consumerism” (Jansen, 2010, p. 13), can be seen as a form of deeply embedded and pervasive structural censorship under conditions of private control of audiovisual production. Subtitle translators opt to self-censor when viewers exert a disturbing influence or when a relatively small number of major audiovisual content creators (e.g., Disney, Netflix, and Sony) and distributors (e.g., TV stations, theatres, and media platforms) are given an even more specific type of censorious power. In the case of Frozen II, Disney asked Youyou Zhang, a professional subtitle translator at Shanghai Film Dubbing Studio, to employ a “de-modernisation” strategy in the translation, minimising the use of currently popular language trends (Yuan, 2019).

The advent of new media and technology has brought about a significant change in the dynamics between local and global influences, leading to the disruption of conventional power structures for information dissemination. An exemplary instance of this transition is the emergence of ‘We Media’, which enables Internet users to actively participate in the production and distribution of news and information (Bowman & Willis, 2003). The rise of audiovisual translation (AVT) via Internet activism, commonly referred to as fansubbing, garnered considerable interest in the 1980s and has been the focus of extensive research since the late 1990s. Perceived as “marginal, peripheral and ‘improper’” (Dwyer, 2018, p. 436), fan translators have the potential to challenge the “narratives circulated by the media elites and the sociopolitical structures they represent” (Pérez-González, 2010, p. 271). The emergence of fansubbing in China in 2001 (Yan & Chen, 2016) can be attributed to the complex and time-consuming procedures and strict censorship of importing foreign audiovisual content, as well as the inadequate quality of official translations (Jiang, 2020). The government has adopted a permissive stance towards non-profit fansubbing groups under the Copyright Law (2020), which allows for the utilisation of a copyrighted work for personal educational purposes, research, or self-amusement without the need to seek permission or provide compensation to the copyright holder (Article 24). Foreign audiovisual property owners are filing an increasing number of lawsuits for copyright violation related to fansubbing. Consequently, the authorities have enacted multiple measures to curb the practice of fansubbing. The Regulations on the Administration of Internet Audiovisual Products (2007) mandates that internet audiovisual products must possess a licence issued by the competent body for radio, film, and television. Since 2005, the National Copyright Administration, the Cyberspace Administration of China, Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, and the Ministry of Public Security have initiated the yearly剑网 [‘Sword at the Internet campaign’] to combat online infringement and piracy.

Once fansubbed audiovisual products flow into the market, they become subject to the limitations implicitly imposed by market forces. Mainstream media platforms have the ability to censor fansubbing groups by selectively filtering or restricting the distribution of specific contents, genres, or forms of audiovisual output and more or less ensure its financial failure. Fansubbing groups strive to distribute their work on mainstream media platforms such as Bilibili, Youku, or IQIYI in order to acquire a wider audience, enhance their popularity, and ultimately achieve financial success by generating revenue through advertisements or paid translation services. Translator D from Team B said that Bilibili previously let fansubbing groups create accounts and freely submit subtitled audiovisual content. However, the current circumstances have undergone a shift. Bilibili manages all comprehensive audiovisual content and requires its audience to purchase a subscription in order to access the whole range of audiovisual products. Baidu Netdisk’s cloud service, which was previously employed by numerous fan-based groups to store and distribute their audiovisual materials as a method to circumvent media platform censorship, is currently being monitored for potentially sensitive information.

Amateur translators in non-official contexts practise self-censorship based on taken-for-granted beliefs due to the absence of direct government enforcement and explicit policies. These beliefs are reinforced by hidden forms of power and domination including societal norms disseminated by the media and education, public consensus, deeply ingrained communal beliefs, and the marketplace. The translation guidelines in Fan-subtitling Team A and B primarily emphasise the criteria for subtitle formats and technical instructions, with less emphasis on translation requirements. Team A’s translation guideline prioritises the task of enticing viewers. The translators should improve their understanding of the content and context, render translations in languages that are both humorous and trendy, and avoid literal translations. This approach will produce products with wide appeal among the audience. Regarding sensitivities, Translator C from Team A indicated that “when there are uncertainties about sensitivities, I would consult with a member of the management team who is also one of the founders for help”. Translator D from Team B also stated that there were few constraints on translation. The members of management engaged in discussions regarding the appropriate handling of sensitive terms. Translator D disclosed that:

A supervisor, who is also a member of management, is assigned the responsibility of overseeing an audiovisual product. The management members engage in discussions in their WeChat group regarding methods whenever harsh discourses about China are present in the original texts.

The management members have divergent perspectives on these taken-for-granted beliefs about sensitivities, resulting in varying levels of self-censorship between Team A and Team B. As an illustration, the term ‘China’ is exclusively addressed in discussions of members of management in Team B when it pertains to unfavourable subject matter. By way of comparison, Team A filters the term ‘China’ in all audiovisual materials using asterisks to mitigate potential complications. Moreover, sensitive countries or regions are translated into alternate names in order to bypass censorship on China’s media platforms. For instance, the term ‘the United States’ is rendered as 美丽国 or 漂亮国 [‘the beautiful country’] instead of using the term 美国, which is the accurate translation of ‘the United States’. According to Loseff (1984) and Gilbert (2013), writers adeptly use ‘Aesopian’ language in contemporary Russian literature and a variety of narrative strategies in the nineteenth-century British novels to evade the rules of censorship. Similarly, the insidious forms of censorship imposed by socially structured forces on fansubbing translators are not merely a suppression and restriction of translations. Instead, these limitations foster extensive discussions among management members and compel translators to develop more innovative and nuanced translation strategies to navigate the restrictions. As a result, unique translation styles are formed, and new vocabularies are generated.

4.3. Resisting social censorship

Power and resistance are intertwined. “Where there is power, there is resistance, and yet, or rather consequently, this resistance is never in a position of exteriority in relation to power” (Foucault, 1976/1978, p. 95). Subtitle translators, motivated by both internal and external factors, strive to negotiate the balance of asymmetrical power and “produce counter-hegemonic discourses and forms of resistance in translations” (Bianchi, 2022, p. 64). They defy the censorship that establishes and marginalises discursive practices in subtitle translation. For example, as observed by Zhang (2015), the multilingual films and TV dramas in local dialects have made significant advancements, garnering positive reception from local audiences, and achieving extraordinarily high audience ratings amidst policies promoting standard Mandarin.

The lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI) community in China has faced social and legal marginalisation. Despite the abolition of the homosexual punishment in the Criminal Law (1997), the Chinese government has not yet legalised the rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI) people. The institutionalised injustice against sexual and gender minority people remains prevalent in China. The media authorities have never explicitly prohibited the narratives and representations that depict homosexual themes in the audiovisual products. Nevertheless, the Internet Audiovisual Programme Content Review Regulations (2017) issued by China Netcasting Services Association under the STARF classifies homosexuality as deviant sexual relationships and behaviours that involve the creation of obscene and pornographic content, as well as vulgar and low-quality entertainment. If internet audiovisual programmes feature content or situations portraying homosexuality, they ought to be altered or removed prior to being broadcasted. If there are significant problems, the programme should not be broadcast in its whole. Furthermore, “Births continued their precipitous post-2016 decline — now down by more than 50 percent in just eight years” (Kirkegaard, 2024), hindering the national development. Thus, the fertility-encouraging practices in public discourses such as education and media, effectively shapes individuals’ unfavourable perception of LGBTI individuals, even in the absence of direct measures to suppress it.

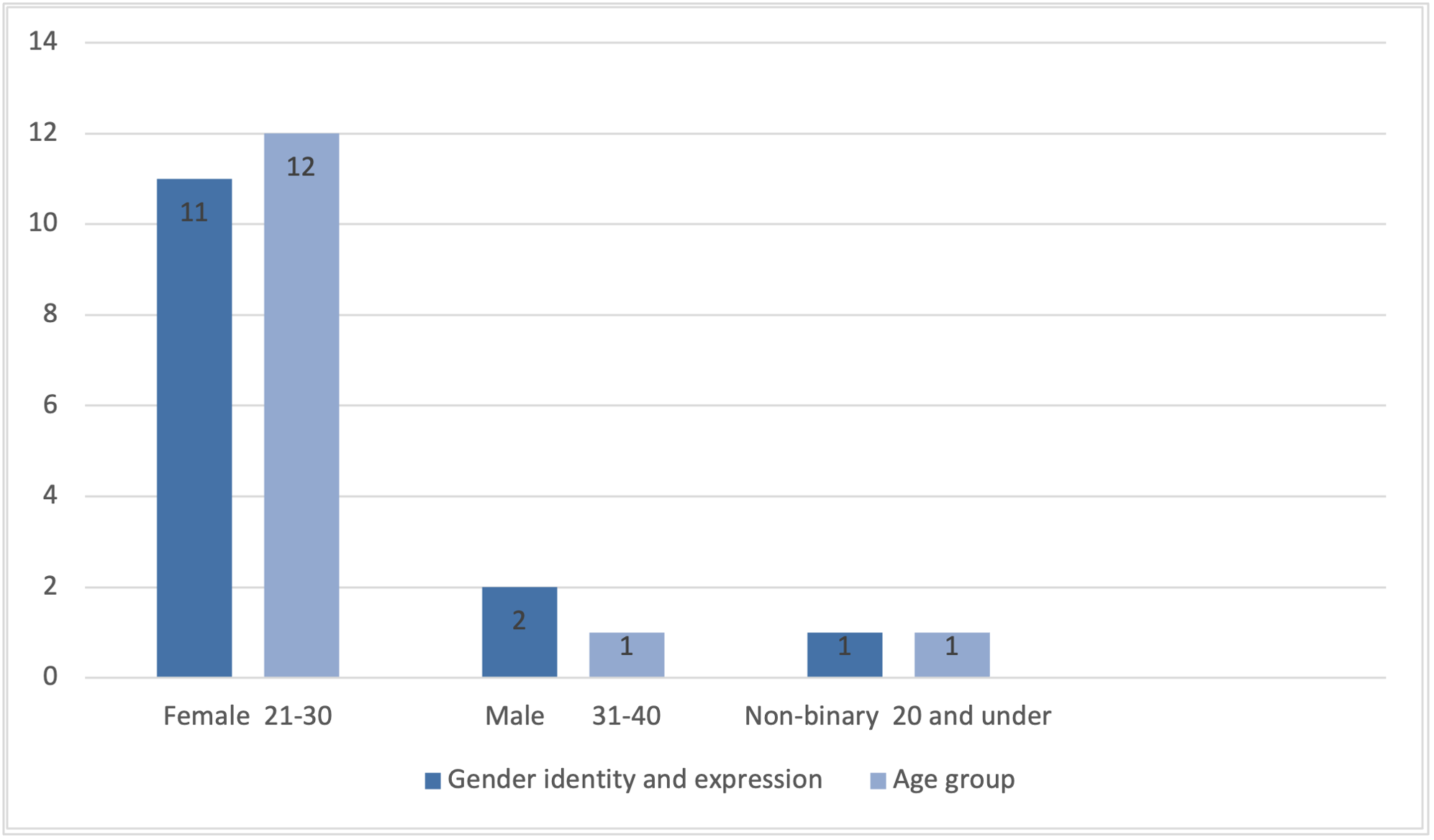

Nevertheless, individuals, particularly the younger generation, have concealed interest in and desire for sexual and gender diversity. The ‘Being LGBTI in China: A National Survey on Social Attitudes towards Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity and Gender Expression’ (United Nations Development Programme, 2016) is the largest national survey conducted in China on sexual and gender diversity issues. Although social homophobia persists in China, the survey conducted with almost 30,000 respondents, primarily born in the 1990s (77.0%), indicates that a substantial majority hold a generally open and accepting attitude towards sexual and gender diversity. The changing attitudes of young people may contribute to the increasing prevalence of audiovisual content featuring sexual and gender diversity in entertainment and artistic works in recent years. Fan-subtitling Team A primarily produces audiovisual content centred around male homosexuality. Based on Figure 1, the analysis of the gender identity and expression, and age group of the 14 samples in Team A reveals that the majority of fansubbers in the sample are young females.

Figure 2. Demographics of the questionnaire sample in Team A.

In China, women constitute the main target audience for homosexual audiovisual content, as their sexuality is considered to be much more fluid compared to men’s. Kanazawa (2017) suggests that women “may have been evolutionarily selected to be sexually fluid in order to allow them to have sex with their cowives in polygynous marriage” (p. 1253).

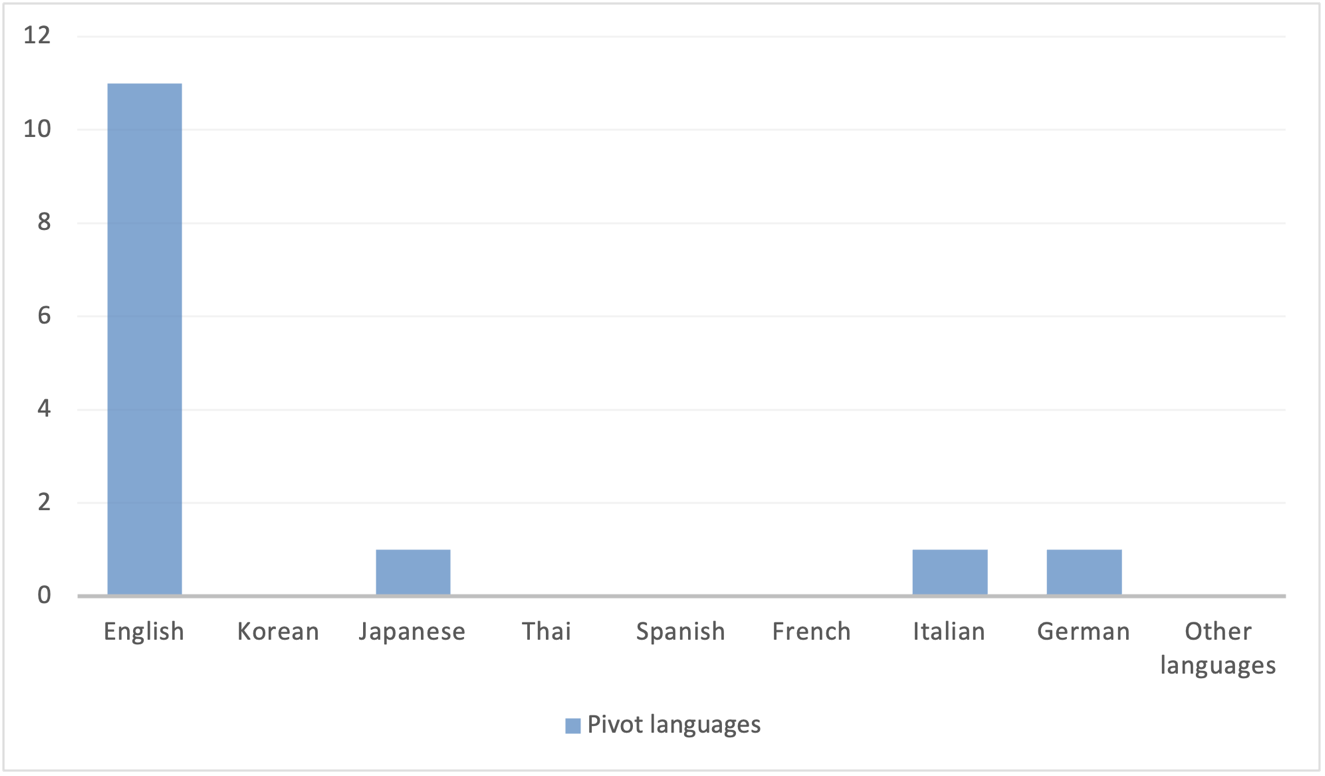

The dynamic character of the media landscape exemplified by the transition from VHS tapes, DVD and VCD, Blu-ray, to streaming (Díaz Cintas & Remael, 2021) has facilitated the growth of machine translation. The widespread use of machine translation as an external factor greatly aids in the translation of subtitles, hence promoting the advancement of Team A. The statistics in the questionnaires indicate that the pilot language from which audiovisual products are translated in Team A is predominantly English, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 3. Pilot languages from which audiovisual products are translated in Team A.

Translator C, an English translator in Team A, stated that the gay-themed audiovisual items in Team A predominantly originated from Southeast Asia. Due to the difficulty in finding translators skilled in these Southeast Asian languages, the sources written in these languages were initially translated into English using machine translation. Afterwards, they were given to English translators. Translator C explained that the marginalised and subordinate homosexual content in Team A set them apart from other competitive fansubbing groups and made them marketable to a wider audience. This may also be interpreted as a strategic choice to accumulate market capital and distinguish themselves in a highly competitive cultural field. Team A capitalises on the controversy surrounding its products and gains advantages from the oppressive censorship.

China’s covert social censorship of the LGBTI community serves as a prime example of the “incitement to discourse” described by Foucault (1976/1978, p. 17). It is currently transforming LGBTI into a topic of discussion, catalysing appropriate discussions and rekindling significant attention. A surge of audiovisual products related to LGBTI can be attributed to several factors. Firstly, it is debt to fundamental intellectual developments of young and well-educated translators, such as the evolving psychological self-perception of individuals in terms of gender identity and their growing acceptance of sexual diversity. Additionally, the emergence of new media, machine translation and technologies has also contributed to the proliferation of such content. The fan translators adeptly harness the sensitive attributes of LGBTI to respond to the heightened curiosity and interest of the audience, and amass market capital, which can be seen as one benefit of censorship in aiding subtitle translation. Censorship “does not necessarily lead to the disappearance of any assertion of autonomy so long as the collective capital of specific traditions, original institutions (clubs, journals, etc.) and their own models is sufficiently great” (Bourdieu, 1992/1996, p. 381). Fansubbing groups can maintain a certain level of autonomy in opposing censorship when they possess robust cultural capital (such as advanced education), social capital (such as fan communities) and economic capital (such as market force).

5. Conclusions

Drawing on new censorship theory, which challenges the common liberal claims that censorship is merely prohibitive, this research examines the collaborative influence of governmental repression, as well as structural and impersonal forms of control on the self-censorship of subtitle translators in China. These opposing and centrifugal forces at work paradoxically impact audiovisual translation, both prohibitive and productive, leading to decisions whether to conform to or circumvent and challenge these regulations.

Subtitle translators employ three distinct self-censorship practices, which vary in their level of subordination to heterogeneous powers depending on their position within the industry. The explicit and evident censorship of adhering to ‘political correctness’ and prioritising maintaining a positive national image, as mandated by state legal control, forms the translation beliefs of the professional translators in the official contexts. These beliefs become deeply ingrained as an internalised ‘habitus’. The regulations in the state media shape the knowledge and opinions of professional translators and the general public. Political censorship takes precedence in official contexts, so compromising the interests of the audience, market benefits, and the accuracy of translations. Different from official translators, fansubbing translators are regulated by quieter and more intangible forms of censorship including market, ingrained collective consciousness, and other social forces of new media, machine translation and technologies. These forms of censorship can inadvertently lead to a substantial surge in conversations and debates revolving around forbidden topics, enhance the marketability of audiovisual products to a wider audience, as well as compel translators to develop more innovative and nuanced translation strategies. As a result, unique translation styles are formed, and new vocabularies are introduced. Censorship can be seen as a productive force that generates new discourses and constructs knowledge in both professional and non-professional contexts. Professional translators tend to adhere to censorship regulations and reproduce dominant discourses mandated by political ideologies. Fansubbing translators adeptly circumvent and challenge censorship to magnify marginalised ideologies.

China’s policies have not kept pace with the long-standing history of practices in audiovisual translation. The audiovisual industry suffers from a dearth of conventions and procedures. Moreover, the structural forms of censorship exert a more significant impact on subtitle translators as a result of the vague and ambiguous language in the state censorship policies. There is a need for more specific policies in the subtitling sector in China to limit subtitle translators from engaging in subtle and implicit forms of structural censorship throughout their evaluation process.

Acknowledgements/Funding

This work is supported by the China Scholarship Council [grant number [202208170015]. I express my gratitude for the perceptive remarks and recommendations provided by the anonymous peer reviewers. I am appreciative of all the subtitle translators whom I contacted.

References

Alfaro de Carvalho, C. (2012). Quality standards or censorship? Language control policies in cable TV subtitles in Brazil. Meta, 57(2), 464–477.

Bianchi, D. (2022). Cultural studies. In F. Zanettin & C. Rundle (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of translation and methodology (pp. 62–77). Routledge.

Billiani, F. (2020). Censorship. In M. Baker & G. Saldanha (Eds.). Routledge encyclopedia of Translation Studies, (3rd ed., pp. 56-60). Routledge.

Bourdieu, P. (1982/1991). Language and symbolic power (G. Raymond & M. Adamson, Trans.). Polity Press.

Bourdieu, P. (1992/1996). The rules of art: Genesis and structure of the literary field (S. Emanuel, Trans.). Stanford University Press.

Bowman, S., & Willis, C. (2003). We media: How audiences are shaping the future of news and information. The American Press Institute.

Bunn, M. (2015). Reimagining repression: New censorship theory and after. History and Theory, 54(1), 25–44.

Burt, R. (1993). Introduction: Ben Jonson and the discourses of censorship. In Licensed by authority: Ben Jonson and the discourses of censorship (pp. 1–25). Cornell University Press.

Burt, R. (1994). Introduction: The ‘new’ censorship. In The administration of aesthetics: Censorship, political criticism, and the public sphere (vol. 7, pp. xi–xxix). University of Minnesota Press.

Butler, J. (1998). Ruled out: Vocabularies of the censor. In R. C. Post (Ed.), Censorship and silencing: Practices of cultural regulation (pp. 247–259).The Getty Research Institute.

Chen, X. (2014). On the three working modes of film and television subtitling in China. Theory and Practice of Contemporary Education, 6(8), 159–161.

Cohen, J. L., & Arato, A. (1992). Civil society and political theory. The MIT Press.

Díaz-Cintas, J. (2019). Film censorship in Franco’s Spain: The transforming power of dubbing. Perspectives: Studies in Translation Theory and Practice, 27(2), 182–200.

Díaz-Cintas, J., & Remael, A. (2021). Subtitling: Concepts and practices. Routledge.

Dwyer, T. (2018). Audiovisual translation and fandom. In Luis Pérez-González (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of audiovisual translation (pp. 436–452). Routledge.

Foucault, M. (1976/1978). The history of sexuality (vol. 1): An introduction (R. Hurley, Trans.). Pantheon

Books.

Gilbert, N. (2013). Better left unsaid: Victorian novels, Hays Code films, and the benefits of

censorship. Stanford University Press.

Green, J. (2005). Introduction. In J. Green & N. J. Karolides, The encyclopedia of censorship (New edition, (pp. xvii–xxii). Facts On File.

Gutiérrez Lanza, C. (2002). Spanish film translation and cultural patronage: The filtering and manipulation of imported material during Franco’s dictatorship. In M. Tymoczko & E. Gentzler (Eds.), Translation and power (pp. 141–159). University of Massachusetts Press.

Izwaini, S. (2015). Translation of taboo expressions in Arabic subtitling. In A. Baczkowska (Ed.), Impoliteness in media discourse (pp. 227–247). Peter Lang.

Izwaini, S. (2017). Censorship and manipulation of subtitling in the Arab World. In J. D. Cintas & K. Nikolić (Eds.), Fast-forwarding with audiovisual translation (pp. 47–57). Multilingual Matters.

Jansen, S. C. (2010). Ambiguities and imperatives of market censorship: The brief history of a critical concept. Westminster Papers in Communication and Culture, 7(2), 12–30.

Jia, Y.C., & Qiao, H. Y. (2004). Efforts to improve the quality of translated films and strengthen the management of them. Motion Picture & Video Technology, 8, 22–24.

Kanazawa, S. (2017). Possible evolutionary origins of human female sexual fluidity. Biological Reviews, 92(3), 1251–1274.

Khoshsaligheh, M., & Ameri, S. (2016). Ideological considerations and practice in official dubbing in Iran. Altre Modernita, 8(15), 232–250.

Kuhiwczak, P. (2009). Censorship as a collaborative project: A systemic approach. In E. N. Chuilleanáin, C. Ó. Cuilleanáin, & D. Parris (Eds.), Translation and censorship: Patterns of communication and interference (pp. 46–56). Four Courts Press.

Li, J. (2012). Ideological and aesthetic constraints on audio-visual translation: Mr. & Mrs. Smith in Chinese. Intercultural Communication Studies, XXI(2), 77–93.

Loseff, L. (1984). On the beneficence of censorship: Aesopian language in modern Russian literature.

Peter Lang.

Maltby, R. (1993). The production code and the Hays Office. In T. Balio (Ed.), Grand design: Hollywood as a modern business enterprise (pp. 37–72). University of California Press.

Mereu, C. (2012). Censorial interferences in the dubbing of foreign films in Fascist Italy: 1927–1943. Meta, 57(2), 294–309.

Mercks, K. (2007). Censorship: a case study of Bohumil Hrabal’s Jarmilka. In J. Neubauer & M. Cornis-Pope (Eds.), History of the literary cultures of East-Central Europe: Junctures and disjunctures in the 19th and 20th Centuries, (vol. 3, pp. 101–111). John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Merkle, D. (2002). Presentation. Traduction, Terminologie, Rédaction, 15(2), 9–18.

Patterson, A. (1984). Censorship and interpretation: The conditions of writing and reading in Early Modern England. University of Wisconsin Press.

Pérez-González, L. (2010). Ad-hocracies of translation activism in the blogosphere: A genealogical case study. In M. Baker, M. Olohan, & M. Calzada (Eds.), Text and context: Essays on translation and interpreting in honour of Ian Mason (pp. 259–287). St Jerome Publishing.

Shambaugh, D. (2013). China goes global: The partial power. Oxford University Press.

Simon, J. (2015). The new censorship: Inside the global battle for media freedom. Columbia University Press.

Wang, D. K. (2020). Censorship and manipulation in audiovisual translation. In Ł. Bogucki & M. Deckert (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of audiovisual translation and media accessibility (pp. 621–643). Palgrave Macmillan.

Williams, B. (2015). Obscenity and film censorship. Cambridge University Press.

Wu, Y. H. (2019). Success of film industry promotion law and its contemporary significance. Film Art, 384(1), 160.

Xiao, Z. W. (2013). Prohibition, politics, and nation-building: A history of film censorship in China. In D. Biltereyst & R. V. Winkel (Eds.), Silencing cinema: Film censorship around the world (pp. 109–130). Palgrave Macmillan.

Yan, D. C., & Chen, X. (2016). The development dilemma and trend of fansubbing groups in China based on the American drama fansubbing groups. Media Observer, 8, 26–28.

Zhang, B. (2017). Chinese fansubbing groups, digital knowledge: Labor (worker) movement and alternative youth culture. China Youth Study, 3, 5–12.

Zhang, C. B. (2004). The translating of screenplays in the mainland of China. Meta, 49(1), 182–192.

Zhang, X. C. (2015). Cinematic multilingualism in China and its subtitling. Quaderns. Revista de Traducció, 22, 385–398.

Websites

China Netcasting Services Association under the STARF. (2017, June 30). Internet Audio-Visual Program Content Review Regulations (网络视听节目内容审核通则). CCTV. https://news.cctv.com/2017/06/30/ARTIm9a7zMhtdUHKCE0OqlfP170630.shtml

Entertainment Capital Theory. (2015, May 14). Who translated “Avengers: Age of Ultron”? Do the four major translation studios monopolise the market? (翻译《复联2》是谁?四大译制片厂垄断市场?)Sina. http://news.sina.com.cn/zl/zatan/2015-05-14/09243697.shtml

Jiang, R. N. (2020, June 20). The development and difficulties of Charity Fansubbing Groups (公益字幕组的生与困). The Paper. https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_7898915

Kirkegaard, J. F. (2024, January 18). China’s population decline is getting close to irreversible. Peterson Institute for International Economics. https://www.piie.com/research/piie-charts/2024/chinas-population-decline-getting-close-irreversible

Liu, L. X. (2008, October 07). Analysis of the Distribution Management Model for Imported Films - A

Case Study of the Chinese Market (进口电影之发行管理模式分析-中国市场案例). Taiwan Cinema. https://taiwancinema.bamid.gov.tw/Articles/ArticlesContent/?ContentUrl=57467

National People’s Congress Standing Committee. (1997). Criminal Law of the People’s Republic of China (中华人民共和国刑法). The State Council of the People’s Republic of China. https://www.spp.gov.cn/spp/fl/201802/t20180206_364975.shtml

National People’s Congress Standing Committee. (2016). Film Industry Promotion Law of the People’s Republic of China (中华人民共和国电影产业促进法). http://www.npc.gov.cn/zgrdw/npc/xinwen/2016-11/07/content_2001625.htm

National People’s Congress Standing Committee. (2020). Copyright Law of the People’s Republic of China (中华人民共和国著作权法). The State Council of the People’s Republic of China. https://www.gov.cn/guoqing/2021-10/29/content_5647633.htm

State Administration of Radio, Film, and Television. (2004). Provisional Regulations on Qualification Access for Film Enterprises (电影企业经营资格准入暂行规定). The State Council of the People’s Republic of China. https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2021-12/14/content_5711915.htm

State Administration of Radio, Film, and Television and Ministry of Industry and Information Technology. (2007). Regulations on the Administration of Internet Audiovisual Products (互联网视听节目服务管理规定). The State Council of the People’s Republic of China. https://www.gov.cn/flfg/2007-12/29/content_847230.htm

State Administration of Radio, Film, and Television. (2001). The Regulations on the Administration of Movies (电影管理条例). The State Council of the People’s Republic of China. https://www.gov.cn/banshi/2005-08/21/content_25117.htm

United Nations Development Programme. (2016). Being LGBTI in China: A National Survey on Social Attitudes towards Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity and Gender Expression. https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/migration/asia_pacific_rbap/UNDP-CH-PEG-Being-LGBT-in-China_EN.pdf

Yuan, X. Y. (2019, December 25). What kind of “magic” is needed to produce a Disney animated film? (译制一部迪士尼动画片,需要什么样的”魔法”?). Beijing Daily.

https://xinwen.bjd.com.cn/content/s5e033998e4b078ea69245126.html

Data availability statement

The project underlying this publication, ‘The visual network analysis in the subtitling industry in China’, includes a Data Management Plan as part of the Certification of Ethical Compliance (DECISION FORM: CUREG-2024-05-55) issued by the Commission Universitaire pour une Recherche Ethique at the University of Geneva. The Data Management Plan specifies that the anonymised questionnaires and interview notes, as well as the documents obtained from the agencies, will not be made publicly available due to their contextualised nature and privacy concerns. The data are protected through non-disclosure agreements between the researcher and the participants.

Disclaimer

The authors are responsible for obtaining permission to use any copyrighted material contained in their article and/or verify whether they may claim fair use.

ORCID 0009-0002-5437-9936, e-mail: lu.yan@etu.unige.ch↩︎