Healthcare interpreting policy in China: Challenges, rationales, and implications

Wanhong Wang, Jilin University

ABSTRACT

Unlike countries that have a long immigration history, China began to welcome a growing number of foreign residents since its opening-up in the 1970s. According to China’s latest census in 2021, about 1 million registered foreigners are staying and residing in China. This study investigates the policies and practices of healthcare interpreting services that support the language needs of foreigners in accessing healthcare in China. On this basis, it looks into the beliefs that governmental authorities and healthcare institutions may hold towards healthcare interpreting. It thus argues that healthcare interpreting in China is still in its preliminary stage, its implementation being patchy and consisting mainly of ad hoc healthcare interpreting. Healthcare interpreting management is indeed rarely overseen at the national, provincial, local, and institutional levels. Overall, as a crucial way to secure health rights, healthcare interpreting has not gained enough attention in China. The profit-driven model applied in the management of some hospitals and the foreign language education policy are both identified as factors influencing healthcare interpreting policy in China.

KEYWORDS

Healthcare interpreting, interpreting policies, interpreting practices, interpreting beliefs, China.

1. Introduction

China has long been regarded as a country from where people emigrate rather than a destination country. However, because of its increasing openness to the outside world since the 1970s, particularly since the country joined the WTO in 2001, China has been attracting a growing number of foreigners who have registered to stay or reside in China. The population of foreigners residing in China has been rising from 0.59 million in 2010 (National Bureau of Statistics 2011) to 850,000 in 2020 (National Bureau of Statistics of China 2021). It is worth noting that in 2018, Wang Zhigang, the Chinese Minister of Science and Technology, stated that over 950,000 foreign residents were working in China (Li and Wang 2019). In addition, there were 490,000 international students (MEPRC 2019), according to the Chinese Ministry of Education, bringing the total number of foreign residents at that time to nearly 1,450,000. Considering the possible drop in numbers due to the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic and China’s closing of its borders during these two years, it is reasonable to infer that the size of the foreign population could have doubled in the past ten years. In line with the Chinese governmental discourse, this paper refers to this community as foreign residents or foreigners rather than immigrants. In terms of the length of their stay, the number of foreigners declined depending on whether they were there for more than five years, between two and five years, between one and two years, between three and six months, or for less than three months. (National Bureau of Statistics of China 2021). The main reasons for staying include, in descending order of population, employment, settlement, studying, unspecified other reasons, business, and visiting relatives (National Bureau of Statistics of China 2021). They settle mainly in the country’s metropolises along the coast such as Guangzhou, Shanghai, Beijing, and the borderland regions in the South, Northeast and Northwest (National Bureau of Statistics of China 2021; Pieke et al. 2019: 6; Zheng 2016).

This demographic landscape is closely related to the fact that China has been developing institutional mechanisms to attract foreign residents, especially high-level professionals and enterprises, and is implementing transformative policies to adapt to demographic changes. Since the 2000s, the Chinese government permits long-term stays (more than six months) of skilled foreigners with knowledge and expertise. Rules for applying for permanent residence permits (PRP) were introduced in 2004 (Zhou 2017). In 2018, China established its first national immigration agency, the National Immigration Administration (NIA), to strengthen immigration management and administration.

Particularly, in recent years, the Chinese government has put forward the strategic plan of “assembling the best minds across the land and drawing fully on their expertise and stepping up efforts to make China a talent-strong country" (Gao 2020). The “talent program” is a representative example of this plan, which “was to show China’s sincerity and determination of constantly opening ourselves” (MOST 2019). On 1st August 2019, twelve measures of immigration policies (National Immigration Administration 2019) were rolled out nationwide to further encourage high-skilled foreign nationals and outstanding foreign students to engage in innovative and entrepreneurial activities in China. Specifically, explicit qualification requirements to apply for visas and resident permits for various durations were specified for the first time for different groups, ranging from foreign students who come to China for an internship to foreign experts, scholars and high-skilled foreign management and technology professionals (The People's Government of Beijing Municipality 2020). Meanwhile, many major Chinese cities, such as Shanghai, put a number of luring policies in place covering areas such as competitive salary, perks, social insurance, and property tax waiver to attract foreign talents, especially high-tech talents.

Moreover, some local governments, such as Guangdong, have put forward temporary work-permit schemes for low-skilled workers from other countries (Public Security Department of Guangdong 2018). While China continues to implement its points-based work permit system aiming to welcome and attract high-level talents, retain the number of skilled labour, and restrict the number of unskilled labour, the cautious but gradual loosening of work permit policy also reveals China’s more welcoming attitude towards foreign residents. Meanwhile, China is attracting more international students than ever before as part of its efforts to open up to other countries, especially those within the Belt and Road Initiative, and to extend its soft power. By 2017, China had become the biggest destination country in Asia for international students. These moves are believed to be a reflection of the governmental “‘top-level’ design approach to policymaking and management, and are an expression of the government’s increasingly proactive attitude towards immigration” (Pieke et al. 2019: 7).

With this growing number of foreign residents comes many challenges for China’s policy framework in terms of regulations, rights and duties with regard to foreign residents. The Exit and Entry Administration Law of the People's Republic of China (2012) stipulates that the rights of foreigners in China are protected on the premise that they obey Chinese laws and regulations. Rules for the Administration of Employment of Foreigners in China stipulate that the income paid to foreign employees shall not be lower than the local minimum wage and that national provisions regarding working hours, rest and vacation, work safety and hygiene, as well as social security, apply to foreign employees (Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security 2017). At the beginning of 2020, the Ministry of Justice released a draft version of the regulation for the administration of foreigners’ permanent residence, which aims to “[…] protect the rights and responsibilities of foreign residents in China” (Gao 2020), though the rights were not specified. In the “Twelve Measures of Immigration Policies” by the National Immigration Administration of the Ministry of Public Security, it was advocated that in areas of large communities of foreign residents, efforts will be made to set up immigration service centres to offer foreigners “national policy consultancy, travel information, legal aid and language and culture services for their convenience during their stay in China” (National Immigration Administration 2019: 12). These policies show that a more comprehensive policy field began to put an emphasis on the need for better services for foreigners (Pieke et al. 2019).

However, equal right to access public services was not explicitly mentioned in these policies. Here public services refer to the services rendered in the public interest in private and public settings. In this sense, healthcare services provided in both public and private healthcare institutions are public services. As a matter of fact, the accessibility to healthcare services should contribute to China’s attractiveness to foreigners and be part of the strategic measures to serve its international talent strategy and “second opening-up”. When considering how to respond to the language needs of foreign residents in healthcare access, interpreting in healthcare settings has been a subject of heated discussions in the field of translation and interpreting studies for decades. However, relevant research in Chinese academia is scant, with a few exceptions (e.g. Su 2009; Zhan and Yan 2013). These existing studies are either general descriptions about community interpreting (社区口译 shequ kouyi) in China, with bare focus on healthcare interpreting (Su 2009), or descriptive case studies on healthcare interpreting provision in one hospital only (Zhan and Yan 2013). To the best of my knowledge, there has not yet been a study on the landscape of healthcare interpreting provision in hospitals in China. More importantly, these studies were all made a decade ago. Thus, this study seeks to provide a more accurate and up-to-date discussion. By drawing on González Núñez’s tripartite framework of translation policy (2013, 2016a, 2016b), in this study, I aim to investigate how language needs of foreign residents in accessing healthcare are addressed in China. On this basis, I probe into the beliefs that governmental authorities and healthcare institutions may hold towards healthcare interpreting, as well as challenges, rationales, and implications of this landscape.

2. Interpreting policy framework

The importance of interpreting in healthcare service regarding the decrease of misdiagnosis, unnecessary tests, medication errors, wrong procedures, avoidable readmissions, and malpractice lawsuits between patients and healthcare practitioners has been discussed and demonstrated in many studies (to name a few: Flores 2005; Karliner et al. 2007). Interpreting policy in public service settings (i.e. how interpreting is planned, practised and how much value has been designated to it), relates closely to equality, non-discrimination, linguistic empowerment, social justice, and recognition (González Núñez 2013, 2016a, 2017, 2019; Meylaerts and González Núñez 2018; Meylaerts 2018). Interpreting policy in this study is derived from a translation policy framework (González Núñez 2013, 2016a, 2016b) that encompasses translation practices, translation beliefs, and translation management, whereby translation refers to both written and oral modes. This translation framework has proved to be methodologically useful in gaining a comprehensive understanding on how linguistic diversity has been addressed in dynamic processes that involve multidimensional and multi-layered interplays of stakeholders, and in exploring governmental beliefs on the integration of linguistic communities (e.g., González Núñez 2017; Li et al. 2017; van Doorslaer and Loogus 2020).

In this study, interpreting management refers to the decisions “made by people in authority to decide a domain’s use or non-use of translation” (González Núñez 2016b: 55). It can be approached through documents ranging from national legislation, such as policies or laws, to a local branch’s in-house guidelines or guidance, and even instructions inside an institution (González Núñez 2016b: 55). Interpreting practices refer to a given community’s actual practices, including who interprets, from which language and into which language. The practices may come “in the footsteps of explicit policy decisions”, i.e. interpreting management, “but they may also be the result of implicit or covert policy” which may or may not be codified via interpreting management at a later point (González Núñez 2016b: 54–55). Interpreting beliefs are the “beliefs that members of a community hold about issues such as what the value is, or is not” of offering interpreting “in certain contexts for certain groups or to achieve certain ends” (González Núñez 2013: 476). Interpreting beliefs are at times explicitly expressed, either through documents relating to interpreting management or in other forms such as comments; but they often remain unspoken, in which case “they can be inferred from practice” (González Núñez 2016b: 55) . In light of this framework, I elucidate how language barriers of foreign residents in healthcare access are addressed in China by exploring interpreting management and practices in section four. On this basis, discussions on interpreting beliefs, as well as challenges, rationales and implications of such interpreting policy are accounted in section five.

3. Data and methodology

This research focuses particularly on Mandarin-English interpreting in healthcare access in Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou. The primary reason for focusing on this language pair is that there is currently no statistic regarding the linguistic repository of foreign residents in China; and my preliminary research indicates that healthcare services in English are provided by hospitals in the study's target cities more frequently than services in French, Korean, Japanese, etc., which are also available in these cities' hospitals to varying degrees. The dataset of this research includes three categories of healthcare institutions: (a) ordinary outpatients of Class A tertiary (AAA) public general/comprehensive hospitals (the most authoritative and high-level ones); (b) VIP outpatients and international health/medical centres affiliated to Class A tertiary (AAA) public general/comprehensive hospitals, i.e., the VIP wings of these hospitals; (c) private (including joint venture) international general hospitals and clinics.

Category |

Type |

Environment |

Medical and exam service price |

Payment method |

Ordinary outpatients of Class A tertiary (AAA) public general hospitals |

Public and not-for-profit |

Usually crowded; longer waiting time |

Relatively low |

China’s basic medical insurance scheme; out-of-pocket payment |

VIP outpatients and international health/medical centres affiliated to Class A tertiary (AAA) public general hospitals |

Public and not-for-profit |

More comfortable |

Multiple times higher than the ordinary outpatients |

Mostly commercial insurance; out-of-pocket payment |

Private (including joint venture) international general hospitals and clinics |

Mostly for profit |

More comfortable |

Multiple times higher than the ordinary outpatients |

Mostly commercial insurance; out-of-pocket payment |

Table 1. Three categories of healthcare institutions

In China, public hospitals offer the majority of healthcare services. The sum total of class A tertiary public hospitals comes from the “China Public Health Statistical Yearbook 2021” (National Health Commission 2021) and the 2020 Public Health Statistical Yearbook of Guangdong Province (Health Commission of Guangdong Province 2021). General ones, rather than specialised ones, among them were sorted out by consulting official websites of these hospitals one by one. Among them, samples of the first category of healthcare institutions under study were selected.

Meanwhile, to my knowledge, there is currently no official resources for the number and list of healthcare institutions belonging to the latter two categories. In the preliminary data collection process, I learned that most services in healthcare institutions in these two categories are not covered by China’s basic medical insurance scheme. These institutions accept health plans offered by certain commercial insurance carriers, as well as out-of-pocket payments. Therefore, I used the lists of premier healthcare institutions I got from two major commercial insurance carriers, MSH China and Cigna & CMB, as references to pick out healthcare institutions belonging to the latter two categories. Three screening conditions for this process are: (1) personal appointment is accepted; (2) having the direct billing service; (3) providing English services. Random sampling method is applied for drawing cases from each category, case size and data size are listed below (Table 2). Taking the first category, the class A tertiary public hospitals, as an example, I sampled 23 general hospitals out of total 55 hospitals of this category in Beijing. Although the dataset is not inclusive of all the healthcare institutions in China, it is representative of the interpreting provision.

City |

Class A tertiary public general hospital/Total Class A tertiary public hospitals (case/total number) |

VIP outpatients and International medical centres affiliated to public general hospitals (case/total number) |

Private international general hospitals (case/total number) |

Beijing |

23/55 |

7/14 |

18/35 |

Shanghai |

19/32 |

14/25 |

31/61 |

Guangzhou |

20/39 |

3/5 |

9/17 |

Total |

62/126 |

24/44 |

58/113 |

Table 2. Sample number and overall number of healthcare institutions

Methodologically, in order to gather interpreting policies at the national, provincial and municipal levels, I gathered online information from websites, including the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security of China, the National Immigration Administration, municipal websites, websites of targeted hospitals in Shanghai, Beijing, and Guangzhou, as well as documents published by professional organisations and health institutions. Data about interpreting practices were mainly collected in two ways. Firstly, the information regarding measures was gathered online from the websites mentioned above; secondly, the information was obtained by contacting the healthcare institutions under scrutiny in this research through calling and inquiring the information desks. Moreover, taking the ‘snowball’ method, I invited 230 foreign residents living in these three cities to fill in a questionnaire online through Wechat about their experience regarding access to healthcare services. Among them, 117 questionnaires were valid. Blank and incomplete ones were weeded out as invalid. Although I made an effort to only include people who could effectively communicate in English in healthcare settings, a few responses suggested that some people used other foreign languages to get healthcare, which were also invalid responses given the scope of this study. Other than confirming the duration of their stay in China and their area of residence, questions seek to examine: (1) what type of hospitals they go to; (2) what language(s) they use when they go to see a doctor in their area, (3) how they communicate with the healthcare professionals. They were requested to choose from several options: I communicate with healthcare professionals in Chinese; doctors delivering services in English; a friend or family member helps me by interpreting; staff members in hospitals help me by interpreting; online interpreting tools; professional interpreters were provided by the hospital; professional interpreters were provided but on my own expense; others. In parallel, this questionnaire triangulates hospitals’ reported practices.

4. Findings and Analysis

4.1 Interpreting management and policies

Healthcare interpreting has not fallen into the remit of any governmental department or organisation. There is no legislation decreed by governmental departments, nor any governmental or institutional policy document about healthcare interpreting; instead, policy documents about general interpreting services promulgated by professional organisations are supposed to be applicable to healthcare interpreting. These documents show the slow but gradual professionalisation process of interpreting. They seek to establish necessary basic principles and protocols for end-users, trainers, service users, interpreters, and service providers to ensure the quality of interpreting services in all settings.

When referring to “interpreting that takes place in public services and in community-based organizations” (Tipton and Furmanek 2016: 2), public service interpreting and community interpreting are two most commonly used and interchangeable terms. In China, 社区口译 (shequ kouyi), which is the literal translation of community interpreting is employed more frequently for such “dialogue interpreting across geonational contexts” (Tipton and Furmanek 2016: 6). Community interpreting, healthcare interpreting, and medical interpreting were mentioned in this context for the first time in the “Translation services – Requirements for interpreting services” issued by the Translators Association of China (TAC 2018), in effect since 2019. Under the jurisdiction of China Foreign Languages Publishing Administration, the TAC is currently the only national social organisation dealing with translation and interpreting and the only professional agent issuing management documents about translation and interpreting in China. According to this document, community interpreting refers to interpreting occurring in a wide variety of private and public settings to support equal access to public services, such as tourism interpreting, social service interpreting, and disaster interpreting. Healthcare/medical interpreting and legal interpreting are listed alongside conference interpreting in its appendix on terminology, with no definition or explanation.

Following international guidelines and requirements for translation and interpreting services such as ISO 13611 (ISO 2014), this document further specifies the required protocols of interpreting and the desired ability of interpreters. Interpreters need to be competent in terms of language proficiency, interpreting skills, cross-cultural awareness, interpersonal communication, the ability to use interpreting equipment, and to acquire and analyse information such as using search engines and terminology management tools, as well as the need to attend continuous training. In addition, the “Code of professional ethics for translators and interpreters” was issued by the TAC (2019) in the same year, which is another headway to professionalise community interpreting. Referring to well-recognised international instruments such as the AIIC Code of Professional Ethics, it makes explicit both ethical principles and code of conduct for translators and interpreters. Unlike the established international documents mentioned above, it advocates the use of technology such as computer assistant tools, which is a pioneering initiative in the field. Though lacking definite indication, these documents imply that the above-mentioned required competencies and the Code of professional ethics are also applicable to interpreters in healthcare settings.

However, these required competencies have not been taken into consideration in “the most authoritative translation and interpretation proficiency accreditation test” in China (CIPG 2019), namely, China Accreditation Test for Translators and Interpreters. Candidates who pass the test are awarded a national occupational qualification certificate issued by the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security, although those without it can still legally practise translation and interpreting at a professional level for profit. In other words, the certificate is more of a “national standard” for certifying the level of translators and interpreters rather than an entry permit into the industry. Only language proficiency and translation/interpreting skills are evaluated in the test. Other competencies such as cultural awareness are supposed to be evaluated by language service providers themselves. As for learning and understanding the Code, this is up to the translators and interpreters to familiarise themselves with its principles. These categories of accreditation for general interpreting are distinctly different from the accredited/certified assessments interpreters have to pass in countries that have a relatively long tradition of community interpreting development. These countries include, for example, the USA, UK, Canada, and Australia, where professional healthcare interpreters need to demonstrate sufficient language proficiency, interpreting skills, as well as an understanding of cultural competence, ethics principles, and codes of conduct (Souza 2020).

Moreover, there is no test accrediting or certifying healthcare interpreters in China. While such accrediting requirements are more or less different across other countries as well, it is commonly agreed (National Board of Certification for MI 2019; NAATI nd.) that other than the competencies of a professional general interpreter, healthcare knowledge such as medical terminology and protocols characteristic of healthcare settings are necessary for professional healthcare interpreters. Having these competencies, interpreters are supposed to be able to deal with medical jargon, negotiate the power imbalance (Granhagen Jungner et al. 2018) between both parties and clarify possible misunderstandings brought by cultural differences. These competencies not only facilitate communication, they also benefit both parties.

On balance, though China’s interpreting policies indicate a professionalising process, interpreting management is far from complete. No policy is in place to secure, encourage or even discourage healthcare interpreting at any administrative level. The interpreting management in China is still centred on general interpreting and mainly conference interpreting. Though healthcare has lately been recognised as a setting for and a field of interpreting service in China, accreditation and training of healthcare interpreters are lacking. This situation is to a large extent the reason why language service providers tend to solely focus on language and interpreting qualifications, with no or little attention to their medical knowledge and understanding of the code of principles – even though they recruit interpreters who may be required to work in healthcare settings (Wang and Li 2020). This assessment of interpreting management in China shows that healthcare interpreting, as well as interpreting in other public service settings, remains a rather blank field in terms of policy-making.

4.2 Interpreting practices in hospitals

In China, most hospitals are public hospitals, with private hospitals being supported by overseas or domestic investors as supplements in the health system. Public hospitals include not only ordinary outpatient services but also VIP outpatients and international medical centres affiliated to these hospitals. The national immigration administration (Welcome to China 2021) posted on its website a set of basic guidelines for foreigners in China to access healthcare (Table 3), which indicates the general structure of healthcare interpreting in China.

Seeing a doctor |

|

Emergency |

Non-emergency |

Option 1 |

Public hospitals |

Option 2 |

Private hospitals |

Table 3. “Guidelines on seeing a doctor” (adapted from Welcome to China)

This study found that in ordinary outpatient services of public general hospitals, ad hoc interpreters are the most commonly used method. Compared to professional interpreters, ad hoc interpreters refer to “untrained, unqualified persons who are called upon to interpret” (WRHA 2013: 2). It is widely acknowledged in academia that healthcare interpreting is, like legal interpreting, a highly professional interpreting. Ad hoc healthcare interpreters include, for example, healthcare staff who are not familiar with the interpreting knowledge, family members (including children), friends, volunteers, and even professional interpreters who usually work in other settings but have not been trained for working in healthcare settings.

In ordinary outpatients under scrutiny in this study, professional interpreting services are not in place, while patients’ companions and staff members in hospitals are allowed to interpret there; healthcare professionals who can speak English are allowed to deliver the service directly as well. It is worth noting that no test is required to assess language proficiency of healthcare professionals, nor is any training provided to gain the necessary knowledge such as cultural awareness, so it is reasonable to infer that the quality is uneven.

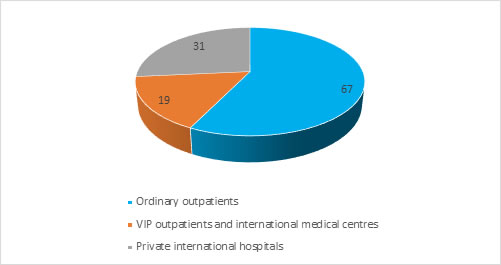

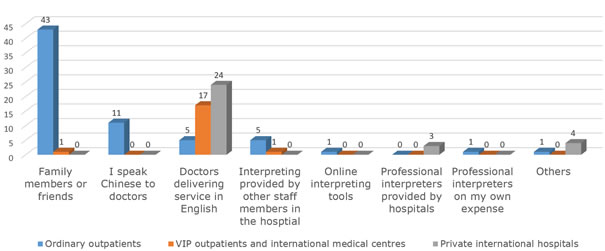

These self-report interpreting practices of ordinary outpatients in public hospitals is overall consistent with the experience of foreign residents reported in questionnaires. According to the questionnaire survey, going to ordinary outpatients in public hospitals is the foremost option for most foreign residents (see Figure 1). Moreover, among the sixty-seven foreign residents attending ordinary outpatient services, forty-three of them were accompanied by English-speaking Chinese friends or family members who acted up as interpreters during the healthcare encounter (see Figure 2). In terms of other measures, communicating in Chinese with doctors is the secondary one, having doctors deliver services in English and interpreting provided by other staff members in hospitals rank the third, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 1. Foreign residents’ self-reported choices of healthcare institution type

Figure 2. Foreign residents' self-reported language measures to access healthcare in three categories of healthcare institutions

Comparatively, according to other healthcare institutions within the scope of this study, i.e. private hospitals and VIP outpatients and international medical centres affiliated to public hospitals, healthcare professionals who are able to speak English are selected to work there. Having these healthcare professionals deliver services in English is the most widely reported interpreting practices in these healthcare institutions, see Table 4 for details. It explains why the majority of foreign residents, seventeen out of nineteen who visit VIP outpatients and international medical centres affiliated to public hospitals and twenty-four out of thirty-one who visit private hospitals, reported that doctors there communicate to them directly in English (see Figure 2).

Nevertheless, in these institutions, Chinese healthcare professionals were selected mainly because they had either obtained a degree oversea or had overseas working experience. Training such as courses promoting cultural competencies was scarcely provided. Meanwhile, as shown in Table 4, in healthcare institutions in these two categories under study, most significantly in private hospitals in Shanghai, doctors coming from other countries around the world (labelled as non-Chinese English-speaking doctors in this study) were recruited, so that they can deliver services directly in English.

|

Multilingual services mode |

Outpatient type and city |

|||||

VIP outpatients and international medical centres affiliated to public hospitals |

Private international hospitals and clinics |

|||||

Beijing |

Shanghai |

Guangzhou |

Beijing |

Shanghai |

Guangzhou |

|

English-speaking doctors (Chinese) |

7 |

13 |

2 |

14 |

19 |

7 |

English-speaking doctors (both Chinese and non-Chinese) |

0 |

1 |

0 |

4 |

10 |

1 |

English-speaking doctors (both Chinese and non-Chinese and in-house interpreters) |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

English-speaking doctors (both Chinese and non-Chinese and contracted interpreters) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

All modes above |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

Table 4. Interpreting service modes in healthcare institutions

Meanwhile, as shown in Table 4, a few of international medical centres affiliated to public hospitals, such as Huiqiao medical centre of Nanfang Hospital, and private hospitals have in-house interpreters. Particularly, Clifford Hospital, a private hospital located in Guangzhou, has both in-hospital interpreters and contracted interpreters provided by external LSPs. Applicants with adequate language proficiency and medical background are preferred in recruiting in-hospital interpreters. Medical knowledge and language ability are tested annually (see also Zhan and Yan 2013), which is a remarkable feature. Three healthcare institutions also report that they cooperate with professional interpreters contracted from LSPs. Nevertheless, most of these so-called professional interpreters may not necessarily be categorised as professional healthcare interpreters. The main reason for such questioning is that medical knowledge is barely taken as a benchmark by LSPs, and a good understanding of ethical principles is not among the top sought-after competencies either (Wang and Li 2020). Drawing on the standards of professional healthcare interpreters mentioned above, healthcare professionals who conduct the role of an interpreter are also ad hoc interpreters as they have not been trained to gain the required cultural competencies. Overall, the issue of healthcare interpreting is a patchy state of affairs in China; it ranges from negligence, and the use of ad hoc interpreters including untrained healthcare professionals, to having institution-based, in-house professional interpreters, the latter option being rare and occasional.

5. Challenges, rationales and interpreting implications

5.1 Healthcare policy planning as a blank field

In balance, healthcare interpreting in China has not been planned and coordinated by neither governmental authorities, professional organisations, healthcare institutions, nor any NGOs. Indeed, the extent to which healthcare interpreting management is designed varies dramatically among countries. Some of these countries, such as Australia (Garrett 2009; Hlavac et al. 2018) and the USA (Youdelman 2019), have explicitly accessible laws and regulations concerning the provision of interpreting in healthcare settings. Many other countries, with or without a long immigration history, such as the UK (González Núñez 2016b) and Korea (Lee et al. 2016), have institution/department-based guidelines or policy documents that regulate and promote healthcare interpreting. Notwithstanding differences between China and these countries regarding political attitudes towards immigrants, the demographic landscape, distinct administrative configurations and the economic-political context, this lack is still very telling.

Planning and policies are necessary because of their symbolic and instrumental power, even though interpreting practices can stand on their own terms. Such management “represent[s] responses (more or less explicit, more or less complete) [sic] in terms of decision-making and public intervention to a given ‘problem’ by an entity endowed with public power and institutional legitimacy” (Serrano and Diaz Fouces 2018: 5-6). These problems or challenges are usually not explicitly apparent, but more often are recognised and selected through many other social issues (Hlavac et al. 2018). That is to say, issues addressed by policy documents are those that are regarded as worthy and crucial for the benefit of the government. In other words, the transformation of the needs of interpreting provision into managing documents usually “carries a strong positive valuation as something desirable and indeed necessary” (Blumczyński 2016: 333).

The needs for healthcare interpreting were foregrounded in China only when there were national events or crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic. When such needs emerge, volunteer interpreters consisting of university faculty members, students majoring in foreign languages and translation and interpreting studies, as well as a relatively smaller number of part-time or full-time interpreters contracted to major language service companies are called upon as volunteers. For instance, during the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games, universities such as Beijing Foreign Studies University, served as the training bases for thousands of such voluntary interpreters and offered multilingual over-the-phone and face-to-face interpreting. Similarly, during the outbreak of COVID-19 in 2020, such volunteer interpreters were called upon again to provide interpreting services for foreigners.

These measures indicate that the language barriers that foreign residents encounter in accessing healthcare services have gained certain attention, especially with regard to building a welcoming national image and demonstrating China’s efficiency in crisis management. However, though the reliance on volunteer interpreters is effective in international events and crisis situations as it meets large-scale demands, it should not undermine the necessity to develop professional healthcare interpreting to address daily need. While healthcare interpreting for foreign residents is crucial to secure health rights, protect a more open national image, and promote the attractiveness of China, it has not gained enough attention in China. Meanwhile, the belief that healthcare interpreting is not a professional field, anyone proficient in English, preferably trained with translation and interpreting skills and knowledge, are competent healthcare interpreters is prevailing.

5.2. Profit-driven vs. rights-driven interpreting provision

Healthcare interpreting in China falls into what Ozolins categorised as an “ad hoc approach” (Ozolins 2010), by which response to an immediate need is sporadically made by individual institutions and even immigrants themselves to find intermediaries such as family members and friends to conduct the interpreting. What is particular to the Chinese context is that the existing institution-based interpreting does not fall into either type of translation (oral or written mode) provision conceptualised by Serrano and Diaz Fouces (2018). According to them, “translation as accommodation” (2018: 8) derives from the “language-as-problem” orientation (Ruiz 1984: 16). In this sense, the translation provision is put in place due to legal pressures to secure equality, though it usually tends to be controlled to provide further incentive for all immigrant communities to learn official languages. In contrast, according to the “translation as right” (Serrano and Diaz Fouces 2018: 6) mode, other languages are seen as resources, translation provision is usually secured by the legislative framework of language rights. In view of these contrasting modes, China’s approach to interpreting provision is more profit-driven than driven by the legislative needs to protect language rights or accommodate linguistic diversity under the legislative obligation of equality and non-discrimination. VIP outpatients, international medical centres of public hospitals, and private hospitals provide services in English; however, they charge a significantly higher amount of money than that of the ordinary outpatients for the same treatment program.

This phenomenon cannot be fully understood without referring to China's health system, particularly the health system reform. In China, the revenue of public hospitals consists of central and local governmental budgets, basic medical and commercial insurances, as well as patients’ personal out-of-pocket expenditure. Since the 1980s, China health system began its transformation along with the dramatic changes of the country’s administrative system and economic policy (Liu and Wang 1991). Since 2000, the central government’s investment in health finance decreased and the responsibility for funding health care services was transferred to provincial and local entities through local taxation (Younger 2016). A few years later, another major change occurred: certain amount of hospitals’ operation budget and healthcare staff salaries were tied to bonuses and revenue generated by their activities, such as the use of profitable new drugs or the latest medical technologies (Younger 2016). This change led to a rapid overall increase in healthcare prices and spending available only to the wealthy population through out-of-pocket payments. Though strict regulations and measures, such as reducing medicine make-up, adjusting pricing of medical services and increasing governmental budget allocation, are incrementally being added since then to improve effectiveness and quality of service while refocusing administration and services at public hospitals on the needs of the general public, public hospitals still have responsibility over their own balance sheets (Xu et al. 2019). In this sense, VIP outpatients and international medical centres of public hospitals, with multiple times higher medical service price, are sources of income. Meanwhile, most of private hospitals are profit-making ones in nature. Hospitals in these two categories usually brand themselves as high-end institutions that provide a more comfortable environment and cutting-edge medical equipment, and offer more privacy than ordinary, often overcrowded, public hospitals. It is therefore no wonder to see why they charge substantially higher fees than ordinary outpatient services.

This phenomenon can be better understood if we take into consideration China’s historical presuppositions towards foreign residents. As one study on foreign employees in China has indicated, there has been an assumption that foreigners are “in a privileged position with high salaries and sufficient social security protection in their home countries upon return from China” (Pieke et al. 2019: 7–8). In the past, especially during the first decade after China’s opening-up, foreigners who came to China were usually wealthier or more prestigious in terms of political, social or professional status. In order to frame its national image, foreigners in China were regarded and treated as VIPs and enjoyed privileges and favourable services, making China appear more accommodating and appealing. Many international healthcare/medical centres in the hospitals under scrutiny in this research came into being for this very reason. For instance, the International Medical Centre in Peking Union Medical College Hospital — China’s top hospital, founded in 1951 — was created mainly to provide high-quality services to diplomatic figures such as foreign ambassadors. Given the luring measures that have been aiming to attract foreign talents, experts and technicians, it is little wonder to see the premier services including interpreting and environment available in international health centres and private hospitals come at a higher price. It is also hardly surprising that they promote their high-end services and cooperation with international commercial insurance companies. In these healthcare institutions, healthcare interpreting is a tool to attract and meet the need of patients with better economic conditions, and thus is a tool for profit-making.

However, this profit-driven model poses huge risks to those who are not covered by commercial insurance, thus creating inequality. The foreign population in China is getting more diverse in terms of profession and income. A large number of foreigners work in less privileged conditions than previously and are not in high-income positions; some may not be able to purchase international medical insurance which is usually expensive. Instead, holders of PRP or Foreigner’s Work Permit are covered by China’s basic medical insurance which can be used to cover most of the basic medical expenses in ordinary outpatients, but not the more expensive ones. Technically speaking, it means that going to ordinary hospitals is the most economically efficient way for them to access healthcare and therefore, according to the result of the questionnaire, the most frequently used method. In other words, it is their preferred option. Therefore, a profit-driven healthcare interpreting poses a huge risk to their health as they need to rely on ad hoc interpreters.

Some studies have shown that in instances when the ad hoc interpreter is a family member or friend, the interests of the patient may be protected (Zendedel et al. 2018). Nevertheless, a more significant proportion of empirical studies (e.g. Flores 2005; Karliner et al. 2007) found that using ad hoc interpreters does not decrease the risk of misdiagnosis, unnecessary tests, medication errors, wrong procedures, avoidable readmissions, etc. The reasons for this are that ad hoc interpreters are usually not able to deal with medical jargons, nor able to negotiate the power imbalance and cultural differences between both parties in an appropriate manner and for the benefit of both parties (Rosenberg et al. 2007). Besides, using family members as ad hoc interpreters raises ethical challenges as far as confidentiality and impartiality are concerned. In such situations, family members may act as the spokesperson, speaking for the patients and leaving the practitioner in doubt about whether the wishes of the patients are being expressed (Hsieh 2015; Rosenberg et al. 2007). What is more, when a family member or friend interprets for the patient, this may become a psychological burden for both the patient and the interpreter (Zendedel et al. 2018). The patient may feel helpless because of the dependence on his/her family member and may not want to feel like a burden on them. Similarly, as an interpreter, the family member or friend may experience significant pressure due to the challenges of the interpreting task and concerns for the safety of the patient. These studies highlight the necessity of having accessible professional interpreting in ordinary outpatient services. They also foreground the potential huge risks posed to both foreign residents and hospitals in China that a lack of interpreting service may cause.

5.3. Foreign language education policy as a factor influencing interpreting policy

The development of healthcare interpreting policies and practices is usually bound by a vast variety of determinants (Corsellis 2008; Garrett 2009, Ozolins 2010; Pöchhacker 1999). They include, for example, administrative configuration, political/social attitudes to immigration, legislative provisions, the extent of linguistic diversity, funding modes, public policy models, opportunities for building coalition, budgetary constraints, service infrastructure and capacity, professional organisation and training, newcomers’ languages competence, workforce supply, institutional culture, personal characteristics of interpreters and healthcare professionals. This list is longer in China as, other than the profit-driven model mentioned above, the foreign language education policy is part of these factors too, which is a distinct feature of China’s healthcare interpreting policy.

Based on the discussion above, the delivery of services in English by Chinese healthcare professionals, or with the assistance of other healthcare professionals, is a common measure in ordinary outpatient services. It is also the main measure adopted in foreign language outpatient services, international medical centres and private hospitals. To understand this phenomenon, one needs to understand China’s foreign language education policy. According to the official education policy, English language courses are compulsory in primary schools from the third year, in middle schools and high schools (Gill 2016). In a general manner, many kindergartens, especially in the larger and more developed cities, have English classes as well (Li 2007). The importance of English is grounded on the fact that it is a subject of the Gaokao (national college entrance examination) in China. In addition, English is also a compulsory subject in universities. In the field of medical education, the majority of published biomedical science research and professional information is in English, and many Chinese universities also have English as the medium of instruction to teach medical academic subjects (Yang et al. 2019). Meanwhile, many healthcare professionals in China need to read and publish articles in foreign languages, mostly English, so as to develop themselves and qualify for the promotion. Therefore, China’s foreign language education policy is, to a very large extent, a crucial factor contributing to the current interpreting practices in Chinese hospitals.

The impact of such a factor may even challenge the professionalisation of healthcare interpreting in China. When the effectiveness of healthcare interpreting provision is discussed, the professionalisation of interpreters is usually taken into consideration. Among the very few studies on community interpreting in China, one (Su 2009) indicates that it has not yet been professionalised in China and that community interpreting has not yet gained recognition as a profession in China. Besides, community interpreting training is insufficient, and interpreting courses in China mainly relate to general interpreting and conference interpreting. Based on the discussion above, these conclusions are applicable to healthcare interpreting at the current stage as well.

Healthcare interpreting can range from ad hoc, informal and amateurish work to a career that involves some training and professional certification (Angelelli 2020; Furmanek 2012; Mikkelson 2004; Pöchhacker 1999; Tipton and Furmanek 2016: 113-164). Professionalisation closely relates to professional training, professional association, entry requirements to the profession, professional development, income, and public perception (Mikkelson 2014). Nevertheless, as Pöchhacker (1999: 128-135) noted, the question of defining what standards, training load, and level of pay professional public service interpreters will have is not easy to answer. The fact that this question is tied up with a constellation of determinants, including “service quality, user expectation, economics of interpreting service provision, extent of multiculturalism, and the legal and social status of migrants” (Lee et al. 2016: 181) may account for the uneven progress toward the professionalisation of community interpreting across the world. As far as the Chinese context is concerned, this question also relates to the status of the interpreter, i.e. who acts as the professional interpreter, which instinctively sounds counter-professional.

Currently, healthcare professionals are to some extent commonly seen as interpreters in hospitals in China. A healthcare professional needs to adhere to their professional codes such as impartiality and confidentiality. If s/he is capable of delivering services in English and is trained for cultural competence, the potential of having healthcare professionals conduct interpreting as "semi-professional interpreters” (Tipton and Furmanek 2016: 189) is greater. In fact, some healthcare professionals told me in an informal manner that many of their colleagues do part-time interpreting for conferences in healthcare fields as they have better knowledge in medical English. If trained healthcare professionals are the main group of professional healthcare interpreters, the professionalisation of healthcare interpreters in China will be on a hugely different path than in many other countries.

Indeed, ethical issues are also salient in this type of “fusion interpreting” (Tipton and Furmanek 2016: 256, 288) in which the healthcare professionals carry out dual duties — healthcare professional and interpreter. In so doing, healthcare professionals are carrying out the duties not listed in the job description. Besides, while there is a need for more research on whether delivering services in a foreign language creates extra mental fatigue and has a negative impact on the outcome of healthcare encounters, it is reasonable to infer that such a risk exists. In addition, one of the main issues this method raises is to determine the working load and salary of healthcare professionals who are capable of delivering services in foreign languages. Overall, China’s foreign language education policy may provide a possible solution to meet the language needs of English-speaking foreign residents, but cautious and careful planning is needed along the way.

6. Conclusion

Unlike countries with a long history of immigration, China is facing the challenge of having a substantial number of foreign residents for the first time in recent years, and needs to break from its previous monolingual (Mandarin) tradition. Generally speaking, healthcare interpreting, as community interpreting in other settings, is initially often carried out on an ad hoc basis by family members, friends, or other volunteers before becoming increasingly systematic, institutionalised, and based on local or regional initiatives and national conventions (Corsellis 2008: 11). Overall, the landscape of healthcare interpreting in China is patchy. It ranges from negligence, the use of ad hoc interpreters including untrained healthcare professionals, to having institution-based, in-house professional interpreters, the latter option being rare and occasional.

Healthcare interpreting management is almost non-existent at the national, provincial, and local levels. As for interpreting practices, ad hoc interpreting acted by companions of patients and untrained staff members in hospitals is basically the sole interpreting through which foreign residents can access healthcare services in public hospitals. In VIP/international medical centres affiliated to public hospitals and private hospitals/clinics, having Chinese healthcare professionals deliver services in English is the more commonly reported practice, whereas their English competence was not measured, training such as courses promoting cultural competencies was scarcely provided. Many interpreting beliefs can be inferred from the investigation. The belief that healthcare interpreting is not a specialised field is prevailing, i.e., anyone who is fluent in English, preferably with translation or interpreting training and working experience, can serve as a healthcare interpreter. Meanwhile, healthcare interpreting is a tool for profit-making in VIP/international healthcare departments and private hospitals.

Overall, these interpreting beliefs, the profit-driven model applied in some hospitals and the foreign language education policy are the main factors determining the current landscape of healthcare interpreting in Chinese healthcare settings. Moreover, as a crucial manner to secure health rights, healthcare interpreting has not gained enough attention in China. With the influx of foreign residents, it is time for China to develop its healthcare interpreting policy, including both management policies and practices, to protect its national, opening-up image, and promote the attractiveness of its soft power.

Acknowledgements

I wish to express my heartfelt thanks to Dr Kathleen Kaess and Dr Piotr Blumczyński for their valuable feedback on earlier versions of this article. I also acknowledge with thanks the insightful comments and suggestions of anonymous peer reviewers. I am also grateful to all the members of organisations and associations I reached out to.

References

Biography

Wanhong Wang is a lecturer at the School of Foreign Language Education at Jilin University in China. She holds a Ph.D. in Translation Studies from Queen’s University Belfast (2020). Her current research interests include translation policy, public service translation and interpreting, and language policy, especially as they relate to inequality, linguistic empowerment, recognition, and social cohesion in multilingual societies.

Wanhong Wang is a lecturer at the School of Foreign Language Education at Jilin University in China. She holds a Ph.D. in Translation Studies from Queen’s University Belfast (2020). Her current research interests include translation policy, public service translation and interpreting, and language policy, especially as they relate to inequality, linguistic empowerment, recognition, and social cohesion in multilingual societies.

ORCID: 0000-0003-4950-2987

Email: wangwanhong@jlu.edu.cn