Translating non-binary coming-out reports: Gender-fair language strategies and use in news articles

Manuel Lardelli, University of Graz

Dagmar Gromann, University of Vienna

ABSTRACT

With the increased visibility of non-binary people, more and more strategies have been proposed for gender-fair language in languages that have grammatical gender, such as German. Gender-fair is used as an umbrella term for gender-inclusive, the explicit inclusion of all genders beyond the binary, and gender-neutral strategies, which omit any gender-specific references in language. An in-depth overview of these strategies has not yet been provided and very few studies analyse their use. This article proposes an in-depth introduction to gender-fair language strategies in German and Italian and their use in news articles. To this end, we compiled a corpus of news articles on the coming out of Demi Lovato as non-binary in both languages, which were all based on and translated from Lovato’s original Twitter post in English. To investigate translation strategies for gender-fair language, we analyse which gender-fair language strategy was applied to translate the tweet. Furthermore, the use and frequency of gender-fair pronouns, nouns, and adjectives were investigated in each article. Results show that misgendering is still very common, especially in Italian. A dominant strategy was not found in German or in Italian; a mix of gender-neutral and gender-inclusive forms was used instead.

KEYWORDS

Gender-fair language, translation, queer translation, non-binary, media translation.

1. Introduction

Translation studies (TS) has long paid attention to gender issues (von Flotow 1991; von Flotow 2016; Nissen 2002; Sabato and Perri 2020; Burton 2010; Spurlin 2014). Paradigms such as feminist translation and, later, queer translation have emerged to address different gender-related topics, such as sexist tropes in translation theory (Chamberlain 1988), the work of feminist and queer translators, the translation of sexist, homophobic and anti-LGBTQIA+ texts, the translation of feminist and queer texts (von Flotow 1991; von Flotow 2016; Burton 2010; Démont 2017), and issues arising from the translation between languages of different grammatical structures in representing gender (Nissen 2002; Di Sabato and Perri 2020).

In recent years, the visibility of non-binary people has increased. Celebrities such as Sam Smith and Demi Lovato have come out as non-binary and trans (binary or not) characters are featured in TV series, such as Sex Education (Nunn 2019-…). Accordingly, gender-fair language strategies to include all genders in discourse have been proposed for some languages (e.g. Hornscheidt 2012; Hornscheidt and Sammla 2021). English is a notional gender language, with lexical gender, such as boy and girl, derivational nouns, such as waiter and waitress, and gender-specific pronouns. The predominant strategy that has emerged is the use of singular they and gender-neutral nouns for non-binary individuals, people whose gender is unknown, and also when the author deliberately chooses not to reveal the gender of a person. In languages with grammatical gender, such as German and Italian, each noun, determiner, pronoun, etc., is gender-inflected. It is therefore more difficult to find a common gender-fair language strategy.

Similar to previous studies on gender-fair translation into Polish (Misiek 2020) and Croatian (Šincek 2020), in this article we present an overview of gender-fair language strategies put forward by researchers and/or the non-binary community for German and Italian. We also present an empirical analysis of media texts on Demi Lovato’s coming out as non-binary as a case study for the use of gender-fair language and representation of non-binary individuals. Even though the texts analysed are not translations in the traditional sense, they represent an instance of transcultural communication. All news articles in our corpus start from Demi Lovato’s Twitter post1, which the article’s authors actively translated, e.g. by using the singular they and adjectives that by definition need to be gender-inflected in Italian. Through descriptive statistics, we then summarised how often strategies for gender-fair language were applied in different word classes, that is, pronouns, nouns, and adjectives. The aim of this study is to discuss and investigate the present situation on gender-fair communication and provide a case study across languages and cultures. Our findings confirm that, unfortunately, non-binary people are not referred to consistently or necessarily correctly, with a higher percentage of misgendering in Italian than in German. This has implications on both the social, i.e. awareness of non-binary genders, and the personal level, i.e. the psychological impact of misgendering.

2. Preliminaries

As the theoretical foundation of the present study, we briefly introduce the interplay of gender and language, gender-fair language and some insights into feminist and queer translation as a field closely related to gender-fair translation.

2.1 Gender and Language

When gender is used in natural language to refer to human beings, it simultaneously refers to the extra-linguistic reality, i.e. to their gender identity (Corbett 1991). Linguistic structures differ greatly across languages, which for gender can be categorised into (i) grammatical gender, (ii) notional gender, and (iii) genderless languages (Stahlberg et al. 2007; Eckert and McConnell-Ginet 2013). In (i), e.g. German and Italian, each noun has a grammatical gender and the assignment is mainly based on formal criteria (Corbett 1991; Comrie 1999). Grammatical gender is defined by Hockett (1958, 231) as “classes of nouns reflected in the behaviour of associated words.” Accordingly, other parts of speech, such as adjectives and articles, must be inflected. In (ii), e.g. English and Swedish, gender is mainly expressed in pronouns and only sometimes in nouns, especially with reference to kinship (e.g. mother/father) or professions. In both (i) and (ii), gender assignment for human referents is mostly based on the extra-linguistic reality (Corbett 1991; Comrie 1999). Linguistic representation of non-binary people can thus be challenging in European languages, since they mainly have binary gender systems (Deutscher 2011). In (iii), e.g. Hungarian or Polish, gender is not expressed, with few exceptions, such as references to kinship.

2.2 Gender-Fair Language

Since second wave feminism, attention has been paid to the expressions of gender in language (von Flotow 2016; Kramer 2019). Amongst others, feminists focused on the use of male generics that, as shown by research in the field of cognitive linguistics (see e.g. Stahlberg and Sczesny 2001; Sczesny et al. 2016), reinforce discrimination and women’s invisibility (Kramer 2019). As a result, different strategies for language as well as language policies to promote equal treatment of men and women have been proposed and introduced (Sczesny et al. 2016).

The term gender-fair subsumes the two different approaches of gender-neutral and gender-inclusive language (Sczesny et al. 2016; Hornscheidt and Sammla 2021). Gender-neutral language seeks to entirely remove gender references from language. For instance, in English chairperson is preferred over chairman (Eckert and McConnell-Ginet 2013). Instead, gender-inclusive language refers to approaches to make all genders visible. For example, in German, a gender star (*) is used to separate word stems and/or male nouns from female endings and thus also include all genders beyond the binary (Hornscheidt 2012; Hornscheidt and Sammla 2021), e.g. Leser*innen (readers).

There is substantial evidence (e.g. Sczesny et al. 2016; Stahlberg et al. 2007) that gender-fair language promotes the visibility of gender with a concrete impact on people’s lives, e.g. their employability. Furthermore, misgendering negatively affects the psychological health of people (McLemore 2018), leading to emotional pain, distress and feelings of identity invalidation.

2.3 Feminist and Queer Translation

For a long time, translation was defined as simply a process of cross-linguistic transfer (Tymoczko 2010). Conceptions started to change in the 1970s and 1980s, first with the influence of Descriptive Translation Studies (Toury 2012; Venuti 2003) and then with the cultural turn (Bassnett and Lefevere 1990). Translation is now more commonly considered a complex process involving questions of ethics, ideology, and political practice, among other aspects.

At the same time, during second wave feminism, authors started to create innovative work known as écriture féminin (feminine writing) to challenge language that was regarded as patriarchal and thus reinforced the primacy of men in society (von Flotow 2016). Such innovative use of language required novel translation strategies, e.g. supplementing, footnoting, and hijacking. Translation scholars began to investigate gender issues in translation practice (Nissen 2002; Sabato and Perri 2020), sexist tropes in translation theory (Chamberlain 1988), the work of feminist translators, the translation of sexist texts, and the translation of feminist texts (von Flotow 2016; von Flotow 1991; Simon 1996). For instance, practitioners such as Godard (1991) and Lotbinière-Harwood (1991) explained their translation strategies that include the creation of neologisms and reclaiming derogatory terms. Both authors conceive translation as a subversive work in which women take on a more active as well as an activist role in society.

In recent years, the influence of queer theory has led to greater attention to other discriminated minorities in TS, in particular, sexualities and identities that challenge the gender binary. As such, publications on queer translation studies have appeared (e.g. Baer and Kaindl 2020; Baer 2020). Research in this field focuses particularly on the translation of homophobic texts and texts featuring members of the LGBTQIA+ community in literature and/or in films (see e.g. Burton 2010; Démont 2017; Baer 2020). The translation of queer texts is particularly relevant for TS because they contain sociolects used by queer characters, such as camp talk, unusual grammar and syntactical structures, e.g. the alternation of male and female gender markers to challenge the gender binary as well as allusions to characters’ or authors’ sexualities via reference to other texts (Amenta 2020). Approaches to queer translation can be (i) misrecognising, (ii) minoritising, and (iii) queer translation. In (i) and (ii) queer elements are either removed from target texts or flattened, whereas in (iii) the source texts’ queerness is maintained through the use of strategies that are similar to feminist translation and include supplementing, footnoting as well as radical changes to texts (Epstein 2017).

3. Work on non-binary language use

Research investigating the translation of texts that feature non-binary individuals, and thus the use of neopronouns and/or neologisms, is still in its infancy (see Lardelli and Gromann 2023). Publications in TS in which trans individuals are mentioned include work which is conceptual in nature, connecting queer identities and translation theory (Robinson 2019). Related scholarship on gendered language focuses on trans men or trans women who use binary language, for example alternating female and male forms to refer to themselves (e.g. Rose 2016).

López (2019; 2021) introduced the distinction between Direct Non-Binary Language (DNL) and Indirect Non-Binary Language (INL). The former aims to make non-binary individuals visible through the introduction of neologisms, neopronouns, and neomorphemes. The latter refers to the use of gender-neutral constructions. Finally, they analyse the translation of a book and two TV series featuring non-binary characters from English into Spanish. They found that non-binary gender identities are usually erased or misgendered, i.e. the character’s sex assigned at birth is used to define their gender identity (López 2021). López (2019; 2021) advocates the use of DNL when referring to non-binary individuals and suggests that pathologising words should not be translated.

Similarly, Misiek (2020) analysed the Polish version of three English-language TV series and found that characters were often misgendered or had their non-binary identity erased. In detailing the differences between English and Polish, Misiek also provided an overview of strategies that are used in Polish today, such as distortion and/or omission of verb endings, use of passive constructions, and the vowel u as a new neutral suffix. Suggestions for the translation of non-binary language include (i) asking the actor interpreting the character how they would like to be represented in Polish, (ii) consulting non-binary or gender-queer communities, (iii) using neuter forms or the vowel u, (iv) using neologisms to describe professions, and (v) using neutral words, e.g. person.

Šincek (2020) compared the Croatian version of a film with the English original and collected articles on Sam Smith’s coming out as non-binary. In this case, too, it was found that non-binary individuals are often misgendered. Additionally, singular they was sometimes translated as ono or oni. The first corresponds to the English it and the second is the third-person plural masculine pronoun. Šincek also conducted interviews with three non-binary individuals and found that they often use gendered forms according to their sex assigned at birth, they switch between gendered forms, use the third-person plural masculine pronoun as an equivalent to singular they, or use gender-neutral constructions.

Finally, Attig (2022) analysed the dubbed and subtitled version of the Netflix series One Day At A Time (2017-2020) and found differences between the two types of translations. Both also had substantial errors. Attig calls for a community-informed translation, i.e. cisgender translators should engage with the queer community to achieve gender-fair translations.

This work in TS therefore suggests multiple ways in which gender-fair language can be incorporated into translations, as well as noting that currently it is not always used where it could be.

4. Gender-Fair German

In German, there are four approaches to gender-fair language, i.e. (i) the rewording of sentences to avoid gendered elements and the use of gender-neutral nouns, (ii) the use of so-called gender characters, such as the gender star (*), to include all genders, (iii) the use of gender characters or new endings, such as the ens forms, to be used in contexts where gender is unknown or irrelevant, and (iv) the introduction of a fourth gender, such as the liminal, through new pronouns and endings for each world class. These approaches are further detailed in the following subsections.

4.1 Gender-Neutral Rewording

The easiest and most immediate approach to gender-fair language is to construct sentences in such a way that they do not mark gender. This can be achieved, amongst others, by (Universität Leipzig 2020; En et al. 2021):

- constructing collective and singular nouns with specific endings and compounds, such as -kraft, -ung, -hilfe, -person, -berechtigte as in Lehrkraft (teaching staff) or Fachperson (specialist);

- referring to functions and institutions instead of people as well as using gender-neutral nouns, such as Person, Mitglied (member), Mensch (human), Ministerium (ministry), Leitung (direction), Team;

- constructing plural nouns through nominalisation of the present participle, e.g. Studierende (students), Lehrende2 (teachers);

- avoiding reference to gender through infinitive and passive constructions.

4.2 Gender-Inclusive Characters

Typographical characters, as depicted in Table 1, may be used to separate word stems and/or male nouns from female endings to make all genders visible. These characters are “pronounced” through a brief pause in spoken language and their use requires some creativity (Universität Leipzig 2020: 4ff; En et al. 2021: 27ff). They are nowadays quite common in German written language (En et al. 2021).

Strategy |

Nouns |

Personal |

Possessives |

Articles |

Question Pronouns |

* |

Student*in |

sie*er, si*er |

ihre*seine |

die*der |

Welche*r? |

_ |

Student_in |

si_e, er_sie |

ihre_seine |

die_der |

Welche_r? |

: |

Student:in |

si:er, er:sie |

ihre:seine |

die:der |

Welche:r? |

/ |

Student/in |

si/er, er/sie |

ihre/seine |

die/der |

Welche/r? |

’ |

Student’in |

si’er, er’sie |

ihre’seine |

die’der |

Welche’r? |

Table 1. Strategies for gender-inclusive German (adapted from AG Feministisch Sprachhandeln 2015: 16)

4.3 Gender-Neutral Characters or Endings

When sex/gender is unknown or irrelevant, male and female endings may be replaced by typographical characters (Hornscheidt 2012: 294ff) or new gender-neutral endings (Hornscheidt and Sammla 2021: 53) (see Table 2 for a selective overview). Such characters are then attached to the verb stem, while neutral endings are attached to the noun stem in order to form nouns. They can also be used in a stand-alone manner to replace word classes, such as pronouns. Hornscheidt and Sammla (2021: 53) propose the use of gender-neutral ens forms that derive from the German word Mensch (human).

Strategy |

Nouns |

Personal |

Possessives |

Articles |

Indefinite Pronouns |

x |

Studierx (Sg.) |

x |

xse |

dix |

x |

* |

Studier* (Sg.) |

* |

*’s |

d* |

* |

-ex |

Studentex (Sg., Pl.) |

ex |

ex |

— |

— |

-ens |

Studentens (Sg., Pl.) |

ens |

ens |

dens |

ens |

Table 2. Selected strategies for gender-neutral German

Some examples formulated with these strategies are (note that the translations into English fail to reflect the diversity of strategies in German, but are simply provided for a better understanding):

- x sollte zukünftig besser auf xes Sprachhandlungen achten (they should in future be more careful with their speech acts)

- einx schlaux Studierx liebt xs Bücher (Hornscheidt 2012: 294) (a smart student loves their books),

- Lann liebt es, mit anderen zu diskutieren. Ex lädt häufig dazu ein, einen Roman zu besprechen (Lann loves to discuss things with others. They frequently invite people to discuss a novel),

- Lann und ex Freundex haben ex Rad bunt angestrichen (Lann and their friend have painted a bike colourfully),

- dens singend Radfahrens (the singing biker),

- einens hat das Recht zu gehorchen (Hornscheidt 2021: 55f) (they have the right to comply).

4.4 Neosystems

The last approach to gender-fair language in German is to develop entirely new grammar systems related to gender that introduce a fourth gender, complementing masculine, feminine, and neuter, in order to make non-binary people visible in language and/or to refer to mixed groups of people. This approach consists of a new inventory of endings for almost each word class.

The NoNa system (Geschlechtsneutrales Deutsch n.d.) was and is being developed by two non-binary activists. As a personal pronoun, they propose the use of hen. Two sets of endings are introduced, i.e. -ai/-ais/-am/-ai for definite articles, relative pronouns, and demonstratives and -t plus a mix of usual masculine and feminine endings for indefinite articles and the negation kein (none, no, not), which results in keint (see Table 3).

Case |

Def. |

Indef. |

Personal |

Possessives |

Demonstr. |

Relative |

Nom. |

Dai |

eint |

hen |

Meint |

diesai |

welchai |

Gen. |

dais |

einter |

hens |

meinter |

diesais |

- |

Dat. |

Dam |

eintem |

hem |

meintem |

diesam |

welcham |

Acc. |

Dai |

eint |

hen |

Meint |

diesai |

welchai |

Table 3. Pronouns and articles according to the NoNa system

As for nouns, this system suggests the use of gender stars to form them, and the adjective declension mixes masculine and feminine endings (see Table 4 for an overview of the declension system).

Case |

Declensions with Indef. Artic. |

Declensions with Def. Artic. |

Nom. |

Eint gute Freund*in |

dai gute Freund*in |

Gen. |

einter guten Freund*in |

dais guten Freund*in |

Dat. |

Eintem guten Freund*in |

dam guten Freund*in |

Acc. |

Eint gute Freund*in |

dai gute Freund*in |

Table 4. Declension system according to the NoNa system (a/the good friend)

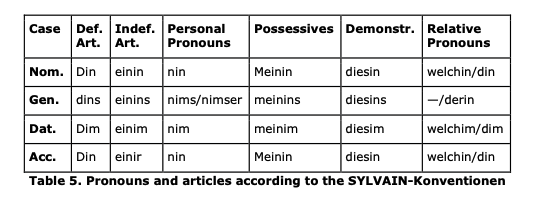

Another system are the so-called SYLVAIN-Konventionen (de Sylvain and Balzer 2008) depicted in Table 5. With this system, a new grammatical gender, the Indefinitivum (also liminales Geschlecht) was introduced. In addition to man and woman, din Lim is to be used for people who reject the gender binary.

Other forms that are proposed include mensch, jemensch, niemensch, and jedmensch in order to replace the indefinite pronouns man (one/you), jemand (someone), niemand (no-one), and jedermann (everybody). Finally, nouns are created by adding the ending -nin to the word stem in singular (e.g. Studentnin) and -ninnen for non-binary individuals or -Ninnen for mixed-gender groups in plural (e.g. StudentNinnen). Consequently, new adjective endings for the indefinite article are proposed (see Table 6), whilst female endings are used for the definite article.

Singular |

||||

Case |

masculine |

Feminine |

liminal |

neutral |

Nom. |

Ein junger Mann |

eine junge Frau |

einin jungin Lim |

ein junges Tier |

Gen. |

eines jungen Mannes |

einer jungen Frau |

einins jungen Lims |

eines jungen Tieres |

Dat. |

Einem jungen Mann |

einer jungen Frau |

einim jungen Lim |

einem jungen Tier |

Acc. |

Einen jungen Mann |

eine junge Frau |

einir jungin Lim |

ein junges Tier |

Table 6. Declension system according to the SYLVAIN-Konventionen (a young man/woman/liminal individual/animal)

In order to illustrate these strategies in language, we provide some examples according to this system:

- Wenn din Feindnin uns bekämpft, ist das gut und nicht schlecht. (If your enemy fights us, it is to be considered good and not bad.)

- Jemensch könnte zugeben, dass nin es war. (They can admit that it was them).

- Niemensch konnte sagen, nin hätte es nicht gewusst. (No-one could say they did not know it).

Heger (2020) proposes the use of the pronoun xier which derives from a fusion of the masculine and feminine pronouns er and sie. As shown in Table 7, definite articles, relative pronouns and possessives can also be built accordingly.

Case |

Personal pronouns |

Relative pron./ |

Possessives |

Nom. |

Xier |

xier |

xiesa Freund_in (otherwise: xieser Freund/xiese Freundin) |

Gen. |

Xieser |

xies |

xiesas Freund_in |

Dat. |

Xiem |

xiem |

xiesam Freund_in |

Acc. |

Xien |

xien |

xiesan Freund_in |

Table 7. Pronouns according to the xier system

The debate on gender-fair language also takes place on social media. For example, there is a private Facebook group called Geschlechtsneutrales Deutsch (gender-neutral German) where people discuss new solutions to overcome the binary structure of German. Recently, the Facebook group administrators founded the Verein für Geschlechtsneutrales Deutsch and, on its website, they propose the so-called De-E system (Verein für Geschlechtsneutrales Deutsch n.d.). In this system, it is suggested that the gender-fair endings -e or -ere as well as -erne should be used to form nouns respectively in singular and plural. The personal pronoun to be used should be hen whilst the possessive pronoun should be deren. In Table 8, an overview of the declension of adjectives and other forms is presented.

Case |

Def. |

Indef. |

No articles |

Other forms |

|

Nom. |

De gute Lehrere |

ein gute Lehrere |

gutern Lehrere |

jedern |

jemand |

Gen. |

dern guten Lehreres |

einern guten Lehreres |

gutern Lehreres |

jedern |

jemandern |

Dat. |

Dern guten Lehrere |

einern guten Lehrere |

gutern Lehrere |

jedern |

jemandern |

Acc. |

De gute Lehrere |

ein gute Lehrere |

gutern Lehrere |

jedern |

jemand |

Table 8. Overview of the De-E system

In German, the pronouns er and sie are used to refer to people. There is no official equivalent to singular they in order to refer to a person whose sex/gender is unknown or irrelevant to the context of the conversation. Nevertheless, there are different solutions to this issue:

- Impersonal, gender-neutral pronouns, such as alle, diejenigen, jene can be used (Universität Leipzig 2020: 7),

- An individual’s name can be repeated instead of using pronouns,

- Sentences can be reworded to avoid the use of pronouns,

- Gender-fair neopronouns can be used (see Table 9 for a selective overview) – it is to be noted that trans, non-binary, inter people may use different, also binary, pronouns. For this reason, it is best to always ask each person for their pronouns (En et al. 2021: 38ff).

Nom. |

Gen. |

Dat. |

Acc. |

Xier |

xieser |

xiem |

xien |

er*sie |

sein*ihr |

ihm*ihr |

ihn*sie |

y |

y |

Y |

y |

they |

their |

them |

them |

dey |

deren |

demm |

demm |

hen |

hens |

hem |

hen |

ens |

ens |

ens |

ens |

nin |

nims |

nim |

nin |

x |

xs |

x |

x |

ex |

ex |

ex |

ex |

per |

pers |

per |

per |

Table 9. Overview of gender-fair pronouns in German (Nibi space n.d.a)

When addressing people, for example in emails, salutations are often gendered in German, e.g. Liebe(r) (Dear) and Frau (Ms.) or Herr (Mr.). Different strategies can be applied to formulate a gender-fair form of address (Hornscheidt and Sammla 2021: 77):

- Salutation followed by name and surname, such as Hallo, Sehr geehrt*, Lieb*, Guten Morgen/Tag;

- Salutation only, e.g. Hallo;

- Frau and Herr can be replaced by Person or Mensch;

- Guten Morgen Person/Mensch followed by surname;

- Gender star or other strategies can be applied, for example for job titles, e.g. Professor*in.

The German language also comprises several terms which imply a binary conception of gender. These include references to kinship, such as Mutter/Vater (mother/father) or Tante/Onkel (aunt/uncle), as well as professions ending in -mann/-frau, e.g. Feuerwehrmann (firefighter) or Obfrau (chairwoman). Lists of gender-inclusive alternatives have been proposed (Nibi space n.d.b). Finally, a gender-fair language is also a stereotype-free language, i.e. free from expressions that ascribe certain characteristics to individual sex/genders are or should be like. For instance, das starke Geschlecht (German for the strong sex) implies that there are only two sexes/genders (En et al.: 33).

5. Gender-Fair Italian

In Italian, the debate on gender-fair language is still restricted to the inclusion of women and, more specifically, to the use of female forms in references to offices and high-level professions (Gheno 2019). To the best of our knowledge, there are also no publications that provide an in-depth overview of the most common strategies for gender-fair language in Italian.

Three approaches can be identified in Italian, namely (i) the use of gender-neutral nouns or constructions in order to avoid any references to gender, (ii) the use of letters or typographical characters to include all genders in language, and (iii) the omission of gendered endings. These are summarised in the next subsections.

5.1 Gender-Neutral Wording

In a similar way to German, sentences in Italian can be written in a way that avoids gender-inflected elements. This can be achieved by the following (Vitiello 2022):

- changing the subject to avoid past participles, since these are gendered in Italian,

- using periphrase, for instance, to replace adjectives with adverbs,

- using neutral and collective nouns as well as impersonal pronouns, such as persona (person), membro (member), personale (personnel), chi (who),

- changing the perspective in the sentences,

- using verbs as subjects to avoid nouns, pronouns, and adjectives,

- using passive and impersonal constructions (which are sometimes gendered, so special care is needed).

5.2 Gender-Inclusive Characters and Symbols

To avoid male generics and also include non-binary people in a discourse, there are different strategies that consist of using the male forms of nouns and replacing the gendered ending with typographical characters or symbols. This can also be done for articles, pronouns, adjectives, and participles. Table 10 gives an overview.

Strategy |

Nouns |

Def. Artic. |

Indef. Artic. |

Pers. Pronouns |

* |

Maestr* |

L* |

Un* |

L*i |

@ |

Maestr@ |

L@ |

Un@ |

L@i |

- |

Maestr- |

L- |

Un- |

- |

u |

Maestru |

Lu |

Unu |

- |

x |

Maestrx |

Lx |

Unx |

- |

y |

Maestry |

Ly |

Uny |

- |

ə/з |

Maestrə (Sg.) |

Lə (Sg.) |

Unə (Sg.) |

Ləi (Sg.) |

Table 10. Gender-inclusive characters and symbols used in Italian

One of the most commonly used strategies seems to be the asterisk (*), since it obtained an entry in the grammar section of the Italian Encyclopaedia Treccani (n.d.), and its origins were described in Marotta and Monaco (2016). However, these strategies, except for schwa (written as ə/з), cannot be pronounced and there is no distinction between singular and plural (Marotta and Monaco 2016). For these reasons, using a schwa has been growing in popularity. Gheno (2019; 2022) promotes its use and nowadays it can be found in books (see the decision of publishing house effequ 2020 and, for example, Meloni and Mibelli 2021), journal articles (e.g. Murgia 2021) as well as on the keyboard of input devices (NeXt 2021). It is also strongly criticised, e.g. because it changes the linguistic structures of Italian (e.g. Arcangeli 2022). Schwa is the phonetic transcription of the IPA symbol for the mid-central vowel. Originally, it was proposed to use ə for singular and з for plural. However, ə is often used for both (see Gheno 2019; 2022).

5.3 Omission of Gendered Endings

This approach is similar to those mentioned in Section 5.2. In the case of symmetrical nouns, i.e. usually ending with ‘o’ for the male gender and ‘a’ for the female, these gendered endings are omitted (e.g. maestr instead of maestro or maestra for teacher). When the nouns are not symmetrical as in lettore/lettrice (male/female reader), the male form of the noun is used, and the vocalic ending is omitted (e.g. lettor). Gendered endings can also be omitted in articles, adjectives, and participles. However, it is not possible to form third-person singular pronouns because the male (lui) and female (lei) differ only for the central vowel whose omission would change said pronouns to li, a definite article.

6. Method

For the present study, we created an event-based corpus on the topic of Demi Lovato’s coming out as non-binary in a Twitter post. The corpus consists of 41 German-language articles found online from Germany, Austria, and Switzerland and 48 Italian-language articles found online that build on and translate the original English post. It was analysed by means of content analysis (Krippendorff 2018) and annotated according to: (i) misgendering, (ii) strategies to translate singular they or types of pronouns to refer to Lovato, (iii) nouns, and in the case of Italian, also (iv) adjectives, specifically the adjective proud used in Lovato’s tweet. These annotations were used to perform deductive category construction. In other words, annotation categories were constructed while reading the articles and descriptive statistical analysis was performed using the statistical analysis software Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) based on these categories. Finally, a detailed analysis of cases of misgendering and different strategies was conducted, which provided the basis for the graphical representation in Section 7.

Previous studies (López 2019; Misiek 2020; Šincek 2020) also analysed whether non-binary individuals in TV series or media outlets were misgendered or described with gender-fair language strategies. The main contributions of the proposed approach are a (i) larger size and multilingual character of corpus compilation, (ii) performance of descriptive statistical analysis of the phenomenon in question, and (iii) a detailed analysis of strategies in use as opposed to proposed strategies. The size is novel in so far that the works by López (2019), Misiek (2020) and Šincek (2020) describe only a few examples instead of a systematic analysis of materials. Furthermore, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to take German and Italian into account.

7. Results

The four main categories used in the corpus analysis are (i) misgendering, (ii) translation of singular they, (iii) translation of nouns, and (iv) translation of adjectives. The fourth category in our corpus only applies to the Italian language, since adjectives were found in the attributive position and, in this case, they are not gender-inflected in German. This section details the results for each category in numbers and graphical representations. The overall corpus size for the German part consisted of 41 texts, while 48 articles were found for Italian.

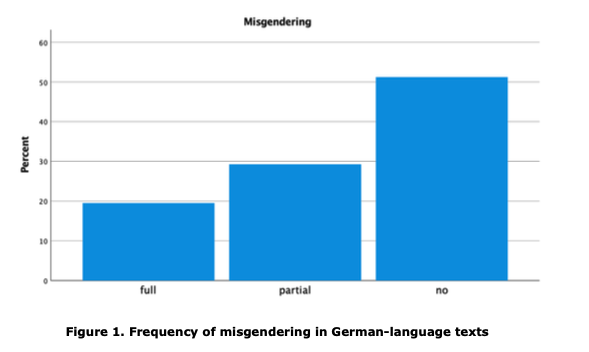

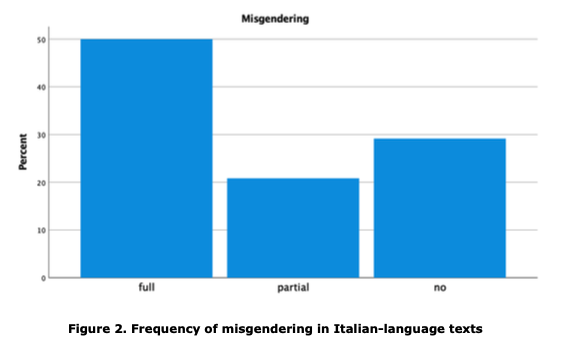

In the 41 German language news texts, Lovato was fully misgendered in 8 articles and partially misgendered in 12. In 21 articles, their gender identity was rightfully respected (see Figure 1). This means that forms of misgendering were found in approximately 48.8% of the cases. The situation is quite different in the 48 Italian-language texts where misgendering occurred in 70.8% of the cases, with 50% full misgendering in the entire text and 20.8% partial misgendering (see Figure 2). This means that in Italian Lovato’s gender identity was correctly addressed in only 29.2% of the corpus.

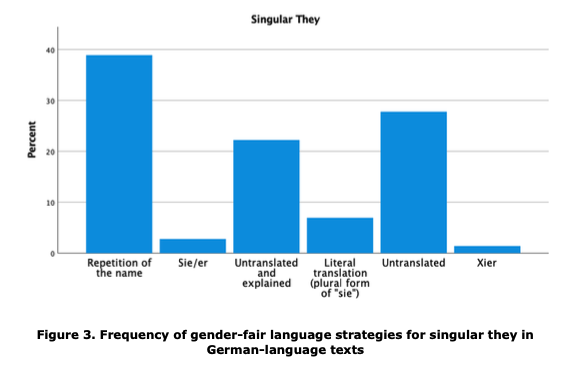

As for the singular they, different strategies were applied both in German and in Italian to translate this pronoun used in the original tweet. In the first case, as can be seen in Figure 3, these include: repetition of the name (38.9%), literal translation of singular they as plural sie (6.9%), use of neopronoun xier (1.4%), and use of the compound pronoun sie/er (2.8%). Additionally, singular they was just left untranslated (27.8%) or it was left untranslated, but its use and meaning was explained in some cases (22.2%). Furthermore, in some texts more than one strategy was used.

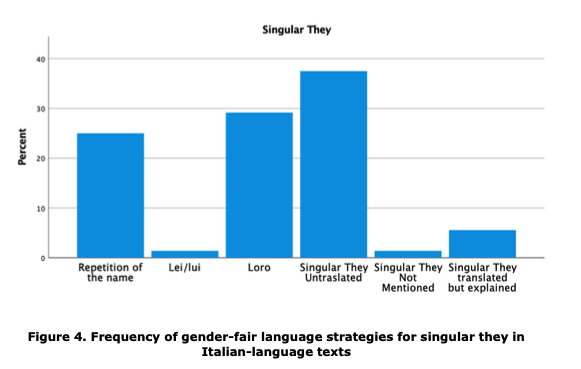

In the case of Italian, as can be seen in Figure 4, the strategies used include: repetition of the name (25%), compound pronoun lui/lei (1.4%) – which is a quite unusual strategy that is not adopted by the non-binary community –, literal translation as loro (29.2%), literal translation with explanation of what it stands for (5.6%), and no translation (37.5%). In just a few cases (1.4%), the pronoun was not mentioned at all. Italian-language articles also used more than one strategy.

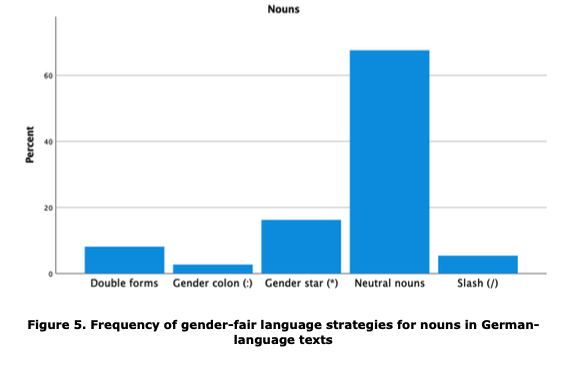

As for strategies used for nouns, in German these were, as can be seen in Figure 5, the use of neutral nouns (67.6%), a gender star (*) (16.2%), both masculine and feminine forms (8.1%), a gender colon (:) (2.7%), and a slash (2%). In four texts, no nouns were used to talk about Lovato’s coming out. Furthermore, in seven articles mixed strategies were used.

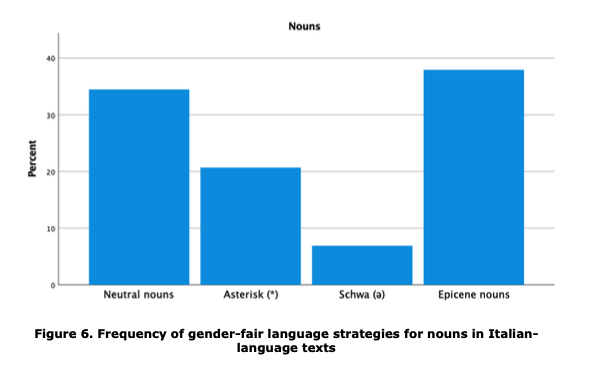

In Italian (see Figure 6), neutral nouns were predominant (34.5%). Other strategies include the use of epicene nouns3 (37.9%), an asterisk (20.7%), and a schwa (6.9%). In this case, too, nouns did not occur in some texts, 18 to be precise. In five texts, mixed strategies were used.

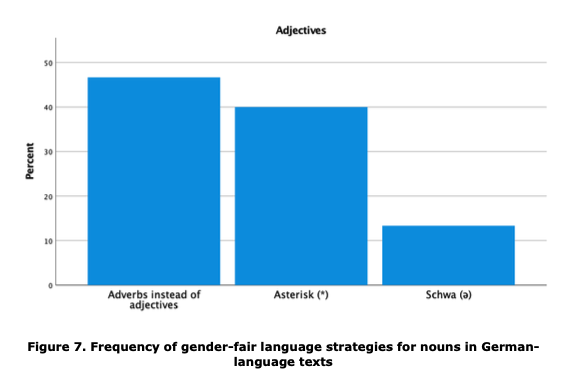

Finally, in 15 Italian-language texts, there was a tentative translation of the adjective proud contained in Lovato’s tweet (see Figure 7). The authors used a sentence construction that allowed them to use the adverb instead of the adjective (46.7%), an asterisk (40%), or a schwa (13.3%).

8. Discussion

These results show that the correct use of gender-fair language is still challenging in German and Italian. Misgendering could frequently be observed in articles in both languages, with a significantly higher occurrence in Italian. This might partially be attributed to the fact that Italian debates about gender inclusive language still centre on the inclusion of women (Gheno 2021) rather than inclusion of non-binary individuals, with very few exceptions (e.g. Gheno 2022 on schwa). German-speaking countries have a longer tradition of gender-fair language policies and strategies (Sczesny et al. 2016), which is reflected in the wealth of literature on the topic (AG Feministisch Sprachhandeln 2015; Hornscheidt 2012; Hornscheidt and Sammla 2021; En et al. 2021) and the slightly better results. One reason for these results that can be observed across languages is a general lack of awareness and inability to detect gender-fair language, which results in misgendering and translations of singular they as plural. While ignorance is no excuse, undetected gender-fair language is unlikely to result in correct gender-fair translations. Raising awareness of gender-fair language strategies across natural languages is thus an important political, social, linguistic, translation-related, and ethical mission to which we hope to contribute with this article.

In cases where gender-fair language was correctly detected, the utilised strategies to translate and use it in the target language were often very different. One of the most frequent and at the same time the safest strategy to avoid misgendering is to replace all co-referential pronouns with the person’s name, a strategy that is among the most common to translate the singular they in both languages. Especially when creating texts themselves, authors tended to repeat the name, whereas pronouns were used when they translated Lovato’s tweet. Some authors opted for using the English they or mistranslated it as plural they in the respective language. In general, few occurrences of gender-inclusive language, such as xier in German pronouns or schwa in Italian nouns, were found, while gender-inclusive characters, such as colon or asterisk, were more frequently observed. While there is no clearly predominant strategy in each language in this corpus, a tendency towards gender-neutral versions and rewording can be observed.

These results indicate a lack of awareness of the wealth of available gender-fair language strategies and a general assumption that gender-neutral language is the safer bet, which, however, as we have seen in this analysis, still easily results in mistranslation and misgendering. The most central societal and ethical implication of this analysis is that these authors knowingly and willingly reported on a non-binary individual and still, in many cases, did not ensure a non-discriminatory or even just correct language. In our view, Attig’s (2022) call for community-informed translation, that is, consultation with the non-binary community on gender-fair language should be extended to community-informed reporting and text creation to correctly address marginalised groups.

Misgendering, mistranslation or constantly alternating the strategy within one and the same text have a strong psychological impact on non-binary individuals who see their identity invalidated or even ridiculed. The issue of gender-fair (mis)translation goes beyond the world of translation. For instance, recently an Italian comedian ridiculed the use of the pronoun they by Lovato, solely based on a mistranslation as plural they. Media should promote the visibility of marginalised groups rather than propagate discrimination. Authors and translators should develop a sensitivity and awareness of different identities, including different gender identities, and seek discrimination-free, community-informed cross-cultural communication.

9. Conclusion

In line with previous research, we find that no predominant strategy for gender-fair language can be found in news articles reporting on events similar to the coming out of a non-binary celebrity. This article presents the multitude of gender-fair language strategies put forward by research and/or non-binary communities for German and Italian that in the empirical analysis of media texts are poorly or even rarely represented. Unfortunately, misgendering still seems to be a common practice. The problem with misgendering in translation is that, even if it is unintentional, it can cause emotional pain and distress to those affected. Moreover, erroneous translations can propagate misconceptions and inhibit social awareness on gender issues.

To further advance this field, future research should be carried out in other language pairs, possibly without English as the source language. Furthermore, insights into the translation process would be needed in order to find out whether the use of gender-fair language impacts translators’ speed and productivity and which strategies would be best suited to produce gender-fair texts without negatively affecting their work. In this regard, it is very important to also investigate the translators’ perspective and attitude towards this issue. This would also include studies on the strategies’ readability and comprehensibility, also considering a wider audience, including people with impairments (e.g. blind individuals who need screen readers), neurodiverse people (e.g. dyslexic individuals), and people with lower language proficiency (e.g. learners with another first language). Finally, post-editing might be worth investigating in this context, since Machine Translation (MT) systems are known to be biased and cannot process gender-neutral forms (Savoldi et al. 2021).

References

- AG Feministisch Sprachhandeln (2015). Was Tun? Sprachhandeln - Aber Wie? W_ortungen Statt Tatenlosigkeit!. Berlin: AG Feministisch Sprachhandeln.

- Amenta, Alessandro (2020). “Tradurre (il) queer. L’esempio della letteratura polacca contemporanea.” Ticontre. Teoria Testo Traduzione 13, 1-17. https://doi.org/10.15168/T3.V0I13.390.

- Arcangeli, Massimo (2022). La lingua scəma: Contro lo schwa (e altri animali). Roma: Castelvecchi.

- Attig, Remy (2021). “LGBTQ+ in Translation: Emerging Research from the Late 2010s.” Translation and Interpreting Studies 16(2), 316–324. https://doi.org/10.1075/tis.20104.att.

- Attig, Remy (2022). “A Call for Community-Informed Translation: Respecting Queer Self-Determination across Linguistic Lines.” Translation and Interpreting Studies. https://doi.org/10.1075/tis.21001.att.

- Baer, Brian James (2020). Queer Theory and Translation Studies: Language, Politics, Desire. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Baer, Brian James and Klaus Kaindl (eds) (2020). Queering Translation, Translating the Queer: Theory, Practice, Activism. Routledge Advances in Translation and Interpreting Studies 28. New York: Routledge.

- Bassnett, Susan and André Lefevere (eds) (1990). Translation, History, and Culture. New York: Pinter Publishers.

- Burton, William M. (2010). “Inverting the Text: A Proposed Queer Translation Praxis.” In Other Words. Special Issue on Translating Queers/Queering Translation 36, 54–68.

- Chamberlain, Lori (1988). “Gender and the Metaphorics of Translation.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 13(3), 454–472. https://doi.org/10.1086/494428.

- Comrie, Bernard (1999). “Grammatical Gender Systems: A Linguist’s Assessment.” Journal of Psycholinguistic Research 28(5), 457–466. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023212225540.

- Corbett, Greville G. (1991). Gender. New York: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139166119.

- De Lotbinière-Harwood, Susanne (1991). Body Bilingual. Montréal: Éditions du Remue-ménage.

- De Sylvain, Cabala and Carsten Balzer (2008). “Die SYLVAIN-Konventionen – Versuch einer „geschlechtergerechten” Grammatik-Transformation der deutschen Sprache.” Liminalis 2, 40–53.

- Démont, Marc (2017). “On Three Modes of Translating Queer Literary Texts.” Brian James Baer and Klaus Kaindl (eds) (2017). Queering Translation, Translating the Queer. New York: Routledge, 157–71.

- Deutscher, Guy (2011). Through the Language Glass: Why the World Looks Different in Other Languages. London: Arrow Books.

- Eckert, Penelope and Sally McConnell-Ginet (2013). Language and Gender. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Epstein, B. J. (2017). “Eradicalization: eradicating the queer in children’s literature.” B. J. Epstein and Robert Gillett (eds) (2017). Queer in Translation. New York: Routledge.

- Gheno, Vera (2019). Femminili Singolari: Il Femminismo è Nelle Parole. Saggi Pop 48. Florence: Effequ.

- Gheno, Vera (2022). Femminili Singolari +: Il Femminismo è Nelle Parole. Florence: Effequ.

- Godard, Barbara (1991). “Translating (With) the Speculum.” TTR : Traduction, Terminologie, Rédaction 4(2), 85-121.

- Hockett, Charles Francis (1958). A Course in Modern Linguistics. New Delhi: Oxford & Ibh Publishing Co.

- Hornscheidt, Lann (2012). Feministische W_orte: ein Lern-, Denk- und Handlungsbuch zu Sprache und Diskriminierung, Gender Studies und feministischer Linguistik. 1. Aufl. Wissen & Praxis 168. Frankfurt a. M: Brandes & Apsel.

- Hornscheidt, Lann and Ja’n Sammla (2021). Wie schreibe ich divers? Wie spreche ich gendergerecht? ein Praxis-Handbuch zu Gender und Sprache. Hiddensee: w_orten & meer.

- Kramer, Elise A. (2019). “Feminist Linguistics and Linguistic Feminisms.” Ellen Lewin and Leni M. Silverstein (eds) (2019). Mapping Feminist Anthropology in the Twenty-First Century. New York: Rutgers University Press, 65–83. https://doi.org/10.36019/9780813574318-005.

- Krippendorff, Klaus (2018). Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology. Los Angeles: SAGE.

- Lardelli, Manuel and Dagmar Gromann (2023). “Gender-Fair (Machine) Translation.” Sheila Castilho et al. (eds) (2023). Proceedings of the New Trends in Translation and Technology Conference - NeTTT 2022. Shoumen: Incoma, 166-177.

- López, Ártemis (2021). “Cuando El Lenguaje Excluye: Consideraciones Sobre El Lenguaje No Binario Indirecto.” Preprint. Open Science Framework. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/t5yxa.

- Marotta, Ilaria and Salvatore Monaco (2016). “Un Linguaggio Più Inclusivo? Rischi e Asterischi Nella Lingua Italiana.” Gender/Sexuality/Italy 3, 45-57. https://doi.org/10.15781/ZS16-XH58.

- McLemore, Kevin A (2018). “A Minority Stress Perspective on Transgender Individuals’ Experiences with Misgendering.” Stigma and Health 3(1), 53–64.

- Meloni, Chiara and Mara Mibelli (2021). Belle di faccia. Tecniche per ribellarsi a un mondo grassofobico. Milano: Mondadori.

- Misiek, Szymon (2020). “Misgendered in Translation?: Genderqueerness in Polish Translations of English-Language Television Series.” Anglica. An International Journal of English Studies 29(2), 165–185. https://doi.org/10.7311/0860-5734.29.2.09.

- Nissen, Uwe Kjær (2002). “Aspects of Translating Gender.” Linguistik Online 11(2), 25-37. https://doi.org/10.13092/lo.11.914.

- Robinson, Douglas (2019). Transgender, translation, translingual address. New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Rose, Emily (2016). “Keeping the Trans in Translation.” TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly 3(3–4), 485–505. https://doi.org/10.1215/23289252-3545179

- Sabato, Bruna Di and Antonio Perri (2020). “Grammatical Gender and Translation: A Cross-Linguistic Overview.” Luise von Flotow and Hala Kamal (eds) (2020). The Routledge Handbook of Translation, Feminism and Gender. London: Routledge, 363–73.

- Savoldi, Beatrice et al. (2021). “Gender Bias in Machine Translation.” Brian Roark and Ani Nenkova (eds) (2021). Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics 9: 845–874. https://doi.org/10.1162/tacl_a_00401.

- Sczesny, Sabine, Magda Formanowicz and Franziska Moser (2016). “Can Gender-Fair Language Reduce Gender Stereotyping and Discrimination?” Frontiers in Psychology 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00025.

- Simon, Sherry (1996). Gender in Translation: Cultural Identity and the Politics of Transmission. Translation Studies. London/New York: Routledge.

- Šincek, Marijana (2020). “ON, ONA, ONO: TRANSLATING GENDER NEUTRAL PRONOUNS INTO CROATIAN.” Zbornik Radova Međunarodnog Simpozija Mladih Anglista, Kroatista i Talijanista, 92–112. https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:172:208617 .

- Spurlin, William J. (2014). “The Gender and Queer Politics of Translation: New Approaches.” Comparative Literature Studies 51(2), 201–214.

- Stahlberg, Dagmar et al. (2007). “Representation of the Sexes in Language.” Klaus Fiedler (ed.) Social Communication. New York: Psychology Press, 163–187.

- Stahlberg, Dagmar and Sabine Sczesny (2001). “Effekte des generischen Maskulinums und alternativer Sprachformen auf den gedanklichen Einbezug von Frauen.” Psychologische Rundschau 52(3), 131–140. https://doi.org/10.1026//0033-3042.52.3.131.

- Toury, Gideon (2012). Descriptive Translation Studies – and beyond: Revised Edition. Benjamins Translation Library. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/btl.100.

- Tymoczko, Maria (ed.) (2010). “Translation, Resistance, Activism: An Overview.” Maria Tymoczko (ed.) Translation, Resistance, Activism. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1-22.

- Venuti, Lawrence (2003). The Translator’s Invisibility. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203360064.

- Von Flotow, Luise (1991). “Feminist Translation: Contexts, Practices and Theories.” TTR : traduction, terminologie, rédaction 4(2), 69-84. https://doi.org/10.7202/037094ar .

- Von Flotow, Luise (2016). Translation and Gender: Translating in the “Era of Feminism.” London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315538563.

Websites

- Effequ (2020). La casa editrice effequ e lo Schwa: la conoscenza deve essere alla portata di "tutt?" https://www.effequ.it/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/fatto_effequ.pdf (consulted 10.04.2022).

- En, Boka et al.(2021). Geschlechtersensible Sprache – Dialog Auf Augenhöhe. https://www.gleichbehandlungsanwaltschaft.gv.at/dam/jcr:8029ba34-d889-4e64-8b15-ab9025c96126/210601_Leitfaden_geschl-Sprache_A5_BF.pdf (consulted 03.04.2022).

- Geschlechtsneutrales Deutsch (n.d.). Das NoNa System, Pronomen. https://geschlechtsneutralesdeutsch.com/das-nona-system/#pronomen (consulted 10.04.2022).

- Heger, Anna (2020). VERSION 3.3: XIER PRONOMEN OHNE GESCHLECHT. https://www.annaheger.de/pronomen33/ (consulted 10.04.2022).

- Italiano Inclusivo (n.d.). Come si scrive. https://italianoinclusivo.it (consulted 10.04.2022).

- López, Ártemis (2019). Tú, yo, elle y el lenguaje no binario. http://lalinternadeltraductor.org/n19/traducir-lenguaje-no-binario.html (consulted 08.04.2022).

- Murgia, Michela (2021). Perché non basta essere Giorgia Meloni. https://espresso.repubblica.it/opinioni/2021/06/07/news/perche_non_basta_essere_giorgia_meloni-304566404/ (consulted 10.04.2022).

- NeXt (2021). Apple introdurrà la schwa per rendere i suoi dispositivi più inclusive. https://www.nextquotidiano.it/apple-schwa-tastiera-iphone-inclusiva/ (consulted 10.04.2022).

- Nibi space (n.d.a). Pronomen. https://nibi.space/pronomen and https://de.pronouns.page/pronomen (consulted 10.04.2022).

- Nibi space (n.d.b). Nicht-binäre Wörter. https://nibi.space/nichtbinäre_wörter (consulted 10.04.2022).

- Treccani (n.d.). Asterisco. https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/asterisco_%28La-grammatica-italiana%29/ (consulted 10.04.2022).

- Universität Leipzig. 2020. Genderleitfaden. Fakultät für Sozialwissenschaften und Philosophie, Institut für Philosophie, Universität Leipzig. https://stura.uni-leipzig.de/sites/stura.uni-leipzig.de/files/dokumente/2020/10/universitaet_leipzig_genderleitfaden.pdf (consulted 07.04.2022).

- Verein für Geschlechtsneutrales Deutsch (n.d.). Kurzübersicht über das De‑e‑System. https://geschlechtsneutral.net/kurzubersicht-uber-das-gesamtsystem/ (consulted 10.04.2022).

- Vitiello, Ruben (2022). Linguaggio inclusivo in italiano: guida pratica per chi scrive per lavoro (e non). https://www.tdm-magazine.it/linguaggio-inclusivo-in-italiano-guida-pratica/ (consulted 10.04.2022).

Filmography

- Calderon Kellett, Gloria and Mike Royce (2017-2020). One Day at a Time. Netflix.

- Nun, Laurie (2019 - …). Sex Education. Netflix.

Data Availability Statement

The materials used in this study are available on Zenodo: 10.5281/zenodo.7808577

Biographies

Manuel Lardelli is currently a doctoral candidate at the University of Graz’s Department for Translation Studies. His research focuses on the translation and post-editing of non-binary gender-fair language as well as on gender bias in machine translation and its socio-technological impact. He was also a research associate at the University of Vienna for the GenderFairMT project.

Manuel Lardelli is currently a doctoral candidate at the University of Graz’s Department for Translation Studies. His research focuses on the translation and post-editing of non-binary gender-fair language as well as on gender bias in machine translation and its socio-technological impact. He was also a research associate at the University of Vienna for the GenderFairMT project.

ORCID: 0000-0002-8976-4108

E-mail: manuel.lardelli@uni-graz.at

Dagmar Gromann is Assistant Professor at the Centre for Translation Studies at the University of Vienna. Her research focuses on language technology as well as information extraction and representation. She is a member of the editorial board of the Semantic Web journal and the Journal of Applied Ontologies, and is National Anchor Point (NAP) for the ELRC and National Competence Center (NCC) for the European Language Grid (ELG).

Dagmar Gromann is Assistant Professor at the Centre for Translation Studies at the University of Vienna. Her research focuses on language technology as well as information extraction and representation. She is a member of the editorial board of the Semantic Web journal and the Journal of Applied Ontologies, and is National Anchor Point (NAP) for the ELRC and National Competence Center (NCC) for the European Language Grid (ELG).

ORCID: 0000-0003-0929-6103

E-mail: dagmar.gromann@univie.ac.at

Notes

Note 1:

The original tweet can be found under https://twitter.com/ddlovato/status/1394913215994155009

Return to this point in the text

Note 2:

It is to be noted that such forms have become quite widespread but are generally not considered as neutral or inclusive anymore as they are associated with maleness (Hornscheidt and Sammla 2021: 49)

Return to this point in the text

Note 3:

Epicene nouns are nouns that have a form only in terms of gender. Gender can usually be inferred through articles.

Return to this point in the text