Fansubs: Audiovisual Translation in an Amateur Environment

Jorge Díaz Cintas, Roehampton University, London

Pablo Muñoz Sánchez, University of Granada, Spain

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this paper is to describe the so-called fansubs, a different type of subtitling carried out by amateur translators. The first part of this study covers both the people and phases involved in the fansubbing process from beginning to end. The second section focuses on the legality and ethics of fansubs. The third part pays attention to the actual translation of fansubs and their unique features, such as the use of translator's notes or special karaoke effects. The paper concludes with a reflection on the work done by fansubbers and the possibilities opened by this mainly Internet phenomenon.

KEYWORDS

Fansubs, fansubbing, anime, audiovisual translation, fan translation, subtitling.

BIOGRAPHY - Jorge Díaz Cintas

Jorge Díaz Cintas is Principal Lecturer in Translation and Spanish at Roehampton University, London, where he is Programme Convener of the MA in Translation. He is the author of Teoria y practica de la subtitulacion: ingles-espanol (Ariel, 2003) and La traduccion audiovisual: el subtitulado (Almar, 2001), and has recently co-authored Audiovisual Translation: Subtitling (St Jerome, fothcoming). He has also written numerous articles on audiovisual translation and has taken part in major international conferences. He is a member of the TransMedia research group and the president of the European Association for Studies in Screen Translation since 2002.

E-mail: j.diaz-cintas@roehampton.ac.uk

BIOGRAPHY - Pablo Muñoz Sánchez

Pablo Muñoz Sánchez is currently studying the second cycle of a BA in Translation and Interpreting at the University of Granada, Spain. He spent a year abroad as an Erasmus student at Dublin City University in Ireland. He is very interested in the areas and genres covered by fan translation and has been a fansubber in the past. He has also localised old videogames from English into Spanish and has published on Internet a handbook in Spanish on the little-known type of localisation known as 'ROM Hacking'.

E-mail: pms_sayans@hotmail.com

Introduction

A fansub is a fan-produced, translated, subtitled version of a Japanese anime programme. Fansubs are a tradition that began with the creation of the first anime clubs back in the 1980s. With the advent of cheap computer software and the availability on Internet of free subbing equipment, they really took off in the mid 1990s.

It would be no exaggeration to state that fansubs are nowadays the most important manifestation of fan translation,having turned into a mass social phenomenon on Internet, as proved by the vast virtual community surrounding them such as websites, chat rooms, and forums. However, this phenomenon seems to have passed unnoticed to the academic community and there are very few studies about this new type of audiovisual translation (Ferrer Simo, 2005), with most authors referring to it only superficially (Díaz Cintas, 2005; Kayahara, 2005).

This study stems primarily from one of the author's experience as a fansubber and aims at presenting the working methodology usually followed when fansubbing. It also attempts to serve as a reflection on the unique features present in this type of amateur subtitling, which have been rarely seen in the professional field (Díaz Cintas, 2005). This study is based on the analysis of examples from both English and Spanish digital fansubs, but it could be very interesting to assess the impact of fansubs in other countries and cultures as well.

The first part of the paper offers a description of the people and stages involved in the fansubbing process, from beginning (source acquisition) to end (distribution). A clear picture of the entire fansubbing process would allow a better understanding of the rest of issues covered in this paper. The second section focuses on the legality and ethics surrounding fansubs. The final sections of the paper discuss the way in which the actual translation is carried out in fansubbing, paying particular attention to some of its most striking peculiarities, especially as far as conventions are concerned. To illustrate some of the points, three examples of translations are presented, highlighting the risks run when translating through a pivot language.

2. The fansubbing process

2.1. Human resources

Generally speaking, the following people are involved in the process:

- Raw providers: Are the people responsible for providing the source material to be used for the translation. A 'raw' is the term used to refer to the original, untranslated video capture of the anime, usually acquired by ripping it off a DVD, VHS or TV source. TV-rips are most common for anime that are still on air in Japan although DVD-rips are used whenever possible as they offer the best image and audio quality.

- Translators: Are in charge of the linguistic transfer. Most of them are not trained in the use of fansub technology and limit their contribution to the translation only. When transferring from Japanese to English most translators are not English native speakers. As it will be discussed later, this is a factor with a crucial impact on the quality of the final translation. Knowledge of the Japanese language is generally not required in the case of translating into other languages because translators usually work from the fansubs translations that have been distributed in English.

- Timers: Timing, which is often also referred to as cueing and spotting in the professional subtitling industry, is the process of defining the in and out times of each subtitle. To do this, timers have to try and strike the best possible balance between "the rhythm, the phrases and the logical divisions of the dialogue and appropriate time units and line lengths for the subtitles he is planning to write" (Ivarsson 1992: 87). The most popular program used for doing this task is Sub Station Alpha(commonly referred to as SSA), although Aegisub, Sabbu and JacoSub are gaining in popularity.

- Typesetters: They are responsible for defining the font styles of the subtitles, for the conventions to be followed, and for formatting the final scripts. In addition, typesetters have traditionally been in charge of synchronising the so-called scenetiming (i.e. the written signs that appear on screen in the original programme) and the opening and ending songs of an anime, usually creating a karaoke effect. However, given the growing importance and complexity of karaokes in fansubs nowadays, a new profile has developed, the so-called karaokeman.

- Editors and proof-readers: Their tasks are to revise the translation in order to make it coherent and to sound natural in the target language, as well as to correct any possible typos. Unlike in the professional world, editors are not supposed to condense the text. Their work becomes essential when the translator is not a native speaker of the target language, i.e. a Japanese speaker translating into English. Knowledge of the source language is preferable albeit not necessary among editors.

- Encoders: They use the provided raw and the final SSA script, which has been formatted by the typesetter and revised by the editors, to produce the subtitled version of a given episode by using an encoding program. The final product is an anime with the soundtrack in the source language and the subtitles in the target language superimposed onto the original images.

Generally speaking, each fansub member only completes an assigned task although different tasks or even the whole process are sometimes performed by the same person, which can help to reduce the risk of errors cropping up in the target text, due to the inaccurate communication of information between the several participants.

As far as the different tasks are concerned, and provided the typesetters and encoders have previous technical experience, timing and translation are reckoned to be the most time-consuming tasks. However, if an episode has many signs - i.e. written inserts in the original photography - the typesetter's work may take more time. Translators with a good knowledge of the languages involved are crucial in fansubbing, the technical dimension being reasonably catered for by a large number of computer-literate fans with little knowledge of foreign languages.

2.2. Technical requirements

Regarding hardware equipment, a computer with an 800 MHz processor and 128 MB RAM should be enough to carry out every task involved in the fansubbing process. Nevertheless, the encoder should work with a fast computer in order to encode at an adequate speed because this process utilises the maximum capacity of the processor. It is therefore recommended to have at least a 1.5 GHz processor to facilitate the encoding of an episode within an acceptable time frame. A high-speed Internet connection is also highly recommended.

In terms of software requirements, each phase of the fansubbing process requires the use of specific programmes:

- Source acquisition: A Peer 2 Peer (P2P) programme like Winny or Bittorrent is used to acquire TV-rips in video format. Ripping software such as AutoGordianKnot or DVD Shrink is necessary in order to produce DVD-rips.

- Translation: A text editor such as Notepad and a video player to watch the anime.

- Timing: Sub Station Alpha (SSA), Aegisub, Sabbu or JacoSub.

- Typesetting: SSA and/or a text editor to add special effects to the subtitles. In order to carry out the scenetiming, Virtual Dub is also required.

- Edition: A text editor and a video player so that the translation can be revised while watching the episode.

- Encoding: Virtual Dub plus the Textsub filter are needed, as well as a video codec, i.e. a device or software module that enables the use of compression for digital video, such as XviD or H.264. The Textsub filter allows for engraving subtitles in SSA format onto a video file. There are also filters that help improve the quality of the image, although their use is optional.

- Distribution: A P2P programme, normally Bitorrent.

2.3. The process

The following description of the fansubbing process is based on the detailed accounts put forward by the Infusion Fansubbing Team (2003).

- The episode raw is obtained and sent to the encoder who will decide whether the source material has enough sound and image quality. The encoder is also in charge of extracting the audio file of the raw by using Virtual Dub, of converting it into an 8-bit mono wave file if required (as in SSA), and of sending it to the timer.

- Once the sound and image quality have been decided on by the encoder, the copy is sent to the translator and the episode can be translated. If need be, the raw can be reduced in quality - and therefore in size - so that it can travel more easily over the Internet. Fansubbers who do not translate directly from Japanese also need to obtain an English fansubbed version. The translator is in charge of transferring into the target language the dialogue as well as the signs and inserts that appear on screen. When subbing a series of which some episodes have already been translated and put on the web, the translator should ideally watch several episodes before attempting the translation, in order to know more about the context and to get a deeper feeling for the subject matter. Likewise, if the anime has an official website, the translator should visit it to get familiar with the names of the characters, the places in which the action takes place and other relevant information. The translator should indicate in the translation whether the subtitles are voices in off or television conversations to make the typesetter's task easier when deciding on the type of font to be used. Once the translated dialogue is finished, it is then sent in the form of a text file to the next person, the timer.

- The translated script is timed with the audio. In doing so, the timer listens to the audio and decides where the subtitles will begin and end. When the timing or spotting of the script is finished, it is saved as SSA format and then sent to the typesetter.

- The typesetter's task is to choose what fonts should be used for dialogue lines, for voices in off, for inner thoughts, and for radio and television conversations among others. Typesetters will decide whether italics or different colours should be used in order to differentiate the information being conveyed, making it easier for the viewer to know who says what. Due care has to be taken when deciding on the type of font and the conventions to be used, since they might have a direct impact on the legibility and readability of the subtitles. As for the scenetiming, the typesetter is in charge of devising the target language signs to be used in order to explain written Japanese characters and inserts that appear on the screen (credits, school signs, newspaper headlines, street names and the like). By using some Textsub filter commands these signs can be made to move around the screen, following the animation. Since this is done by hand, using a text editor, it can be quite time-consuming. The new SSA script is then passed on to the editor.

- The karaokes for the opening and ending songs are usually done when translating the first episode of an anime series and used every time the same songs are included in subsequent episodes. If the opening and/or ending songs change in other episodes, new translations are obviously called for. Thus, karaoke transcripts are always included in the final script of every episode. This step to karaoke the songs involves either the timer or the typesetter - or, more recently, the karaokeman - who is in charge of timing each syllable independently, letting if fill up with a different colour as the word is being sung. This can be done reasonably easily by using the special karaoke mode in Sub Station Alpha or Aegisub, which adjust the timing properly in a similar way as the typesetter does the scenetiming. Karaokes usually include the translation of the Japanese song together with the transcription of the original lyric in both romaji (the transliteration of Japanese to the Latin alphabet) and kanji (Japanese characters). In addition, fansub credits are also normally shown during the opening song, as Example 1 below shows, which can produce an overload of information on the part of the viewer.

Example 1

Anime: Kanon |

|

- Editors are in charge of revising the target text and in order to do it well they should ideally watch the original raw - if they know the Japanese language - or the English fansubbed version - when the subtitles have not being directly translated from the Japanese. Apart from correcting typos, editors should also check that the translated text follows the content of the original or the pivot language and does not clash with the images. Since, as mentioned before, translators are not always experts in the English language, editing becomes a very important step in fansubbing. Should any changes or modifications be necessary, the translator ought to be contacted and asked before the final translated version is released. After all the necessary changes have been made and agreed by the translator, the SSA script is considered to be final and is then sent to the encoder.

- Encoders usually work with the open source programme Virtual Dub. They load a script containing both the raw and the final SSA script and decide which parameters should be used in order to optimise the image quality as well as the size of the video by configuring a video codec. The standard size for an episode is 174 to 230 MB and one of the most used video codecs is the so-called XviD, although H.264 is increasingly gaining in popularity. If required, special filters may be used to clean and boost the quality of the image although they tend to slow the encoding process.

- A Quality Check (QC) by the translator or the editor is usually carried out before releasing a fansubbed episode. Any problems like typos, subtitles not properly synchronised with the audio, or glitches in the image are noted down and corrected. The encoder should then use the corrected SSA script and/or new raw if necessary to re-encode the episode. The resulting video will be considered final and ready for releasing to the public.

- To spread the fansubbed episode among fans the most preferred distribution methods are Bittorrent and XDCC (a transfer protocol of the Internet Relay Chat, also known as IRC). Distributors start serving the file for viewers to download, and someone in the group notifies various fansub websites of the release, to let more people know of its existence. Popular websites for downloading fansubs are Animesuki for English fansubs and Frozen-Layer Network for Spanish fansubs.

The above steps illustrate the way fansubs are done, although the process can undergo several variations. The editing stage, for instance, can take place before the typesetting. As with standard subtitling, teamwork is essential in order to produce a high quality fansubbed programme.

3. The legality and ethics of fansubs

Barely a decade ago, Japanese anime programmes were not easy to get outside of Asia. In the case of the USA, very few anime companies existed in the commercial sector. They would only bring in a limited number of titles as they were small firms, lacked the funds, and the market was not big enough to justify the import of more shows. Spain, on the other hand, was enjoying the commercial distribution of a significant number of anime shows during the 1990's mostly imported from Italy, where the translation of anime was being subject to censorship (Andrei, 1992). However, the distribution in Spain was not without upheavals, and some parents associations exerted pressure on the mass media to stop the broadcast of some anime shows and to boycott the import of some others. For example, Los caballeros del Zodiaco (Saint Seiya in Japanese), a very popular anime amongst fans, was never shown on Spanish public TV again due to its presumed violent content.

As a way to popularise anime programmes and also to encourage certain titles to be distributed in the USA, and beyond, some anime fans decided to create their own fansubs in the early-90s. At the time, Internet had not as many users as it has nowadays, and these pioneers used to distribute fansubbed anime on videotapes rather than in digital format.

Traditionally, it has been implicitly acknowledged by fansubbers as well as by Japanese copyright holders that the free distribution of fansubs can have a very positive impact in the promotion of a given anime series in other countries. This approach, that could be considered a sort of gentlemen's agreement, might well explain why there have been practically no confrontations between translators and copyright holders. Indeed, one of the self-imposed rules adopted by fansub groups has always been to stop the free distribution on Internet of a particular anime once the programme or series has been licensed for commercial distribution. It is therefore common to read the sentence "stop distribution if this anime gets licensed in your country" in most fansubbed shows. Commercial, subtitled versions of anime shows are generally considered to be of higher quality, both technically and linguistically, than fansubs.

Phillips (2003) claims that without proper international treaties fansub groups that operate outside Japan cannot be affected by Japanese copyright. However, if the translated fansub is to be distributed in a country that recognises Japan's copyright jurisdiction, the translation would therefore fall under Japanese copyright legislation. As can be expected, the situation gets extremely complex when the distribution is done via Internet, a medium in which borders and nationalities are difficult to be delineated. In addition, the USA has one clause of interest in its copyright law - Fair Use -, which can be applied if the translated copy is distributed with no intent to make profit, and is done either for educational purposes, or for the purpose of educating another. Although this tends to be the underlying spirit of most fansubs, it is not always the case and some people try to sell fansubs on the Internet and even during prominent anime events (Script Club Discussion Forum).

The popularity of anime has recently grown in most countries. Anime companies working in the USA can make significant profits, which can then be re-invested to license more, new shows. And the same can be said of the Spanish market, with distributors like Selecta Vision or Jonu Media licensing anime more frequently than ever before. In addition, and thanks to Internet, the popularity of fansubbing has grown exponentially, with an ever-increasing number of people creating their amateur subtitles. With the advent of high-speed Internet connexions, fansub groups have decided to stop the distribution on videotapes and start instead the release of digital anime on Internet.

This development has coincided with a growing discontent amongst Japanese companies against fansubbers, who see them as damaging to the market. Several factors are behind this change in attitude. Firstly, the increase in popularity of anime worldwide means that there is now a healthy market for them and many new series no longer need fansubs as a form of promotion. Several Japanese companies have already threatened to take legal action against fansubbers despite supporters' arguments that fansubs are sometimes the only way Western audiences can view certain anime. Secondly, bootleggers selling fansubs in seemingly legitimate packaging are proving detrimental for sales in some parts of the world. Thirdly, the fansub phenomenon is growing wider and encompassing other language combinations and genres, including films; a development seen with suspicion by many distributors who view it as another instance of illegal piracy.

On occasions, the opposing interests of fansubbers and distributors have led to head-on confrontation. In 2003, the long-awaited Ninja Scroll TV series was aired for the first time in Japan. Urban Vision, a USA anime distributor, obtained the licence for the distribution of this series on DVD and, according to the ethics of fansubs (Animesuki, 2003), fansubbed versions of this title were therefore expected to be stopped. However, the group Anime Junkies did not care about the USA licence and continued to fansub this anime, believing they had every right to fansub licensed material and distribute it as an inexpensive, immediate alternative to the DVD release (Macdonald, 2003).

Lack of enforcement of copyright laws in terms of unlicensed fansubs may be the result of several different factors (Phillips, 2003). Some companies may think that the early introduction of some episodes is beneficial for the series and its popularity. Others may tolerate a 'fan-activity' as long as it does not become too damaging to sales. And yet other companies may not want to, or be able to, invest the time and money necessary to prosecute foreign violations of their copyright. The fact remains that, in the end, regardless of ethics, or motive, fansubs are technically illegal.

4. The translation of fansubs

Despite the claims of many scholars that translators should translate into their mother tongue (Newmark, 1988:3), it is interesting to note that in the case of English fansubs there are many translators whose mother tongue is not English - i.e. Japanese native speakers producing subtitles in English. As mentioned before, fansubbing takes this reality into account allowing for the participation of editors and proof-readers in the process. Although it is true that the translator's reduced proficiency in the foreign language may jeopardise the validity of the final product (Stewart, 2000:206), it seems that one of the overriding factors in fansubbing is the need to fully understand the Japanese source text, both linguistically and culturally. The sheer dearth of English native speakers fluent in Japanese and the fact that these translations are done for free are factors that cannot be underestimated either.

Given this state of affairs, it is not surprising that the quality of the translations circulating on Internet is very often below par, although on occasions some fansubs do not have anything to envy to the quality of the licensed translations, commercially distributed on DVD or broadcast on television.

One of the most interesting facts about fansubs is that translators know that they are addressing a rather special audience made up of people very interested in the world of anime and, by extension, in Japanese culture. This is one of the main reasons why translators tend to stay close to the original text and to preserve some of the cultural idiosyncrasies of the original in the target text. For instance, in Japan, people prefer to use the family surname rather than the first name to address each other, and they adhere to a linguistic protocol that is based on social distance. They use special suffixes like -kun for boy teenagers and -sensei for teachers. In the fansubbed version of the anime DNA^2, one of the main characters is addressed as Momonari-kun (his family surname + boy teenager suffix), whereas in the Spanish commercial version he is addressed as Junta (his first name). In this particular case, it can be argued that the audience of the fansub can better identify the status of their favourite character. Though more research is needed in the area, it seems safe to assume that consumers of fansubs are generally exposed to more foreign cultural idiosyncrasies than other viewers.

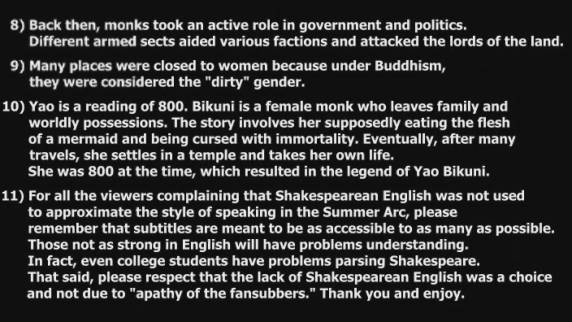

Another distinctive feature of fansubbing is the fact that certain cultural referents such as the names of places, traditions and other celebrations are explained by using translator's notes and glosses. These notes, which are usually placed at the top of the screen, appear and disappear together with the subtitles that they accompany, making their reading rather challenging. Firstly, because of the limited time available to read all the information, and secondly, because of having to read the text against normal practice, i.e. first the line(s) at the bottom and then the line(s) at the top. When glosses are used, they tend to be written in a different colour in the same subtitle. It is also interesting to notice that some fansubbers include translation notes or comments before the episode starts, in a similar fashion as a preface to a book. An interesting example can be found in the opening credits of Air TV, episode eight, where point number 11 deals exclusively with issues relating to the translation and justifies the overall fansubbing approach:

Example 2

Fansub: Air TV |

|

These conventions have never been used in professional subtitling in the past since one of the golden rules has always been that the best subtitles are those that pass unnoticed to the viewer. This way of understanding subtitling has led to the imperative for the subtitler to domesticate the translation and to be as invisible as possible. However, some of these new conventions are nowadays making an appearance in the commercial versions of some programmes (Díaz Cintas, 2005).

In a pioneering article, Ferrer Simo (2005) offers a comprehensive list of the key features that define fansubs. When compared to professional subtitling, the following main differences can be established as far as presentation is concerned:

- Use of different fonts throughout the same programme.

- Use of colours to identify different actors.

- Use of subtitles of more than two lines (up to four lines).

- Use of notes at the top of the screen.

- Use of glosses in the body of the subtitles.

- The position of subtitles varies on the screen (scenetiming).

- Karaoke subtitling for opening and ending songs.

- Adding of information regarding fansubbers.

- Translation of opening and closing credits.

Only time will tell whether all these conventions will become a feature of future subtitling.

5. Examples of translation errors

Given the amateur nature of this translational practice and the languages involved, particularly Japanese, mistakes tend to be fairly common. Let us now take a look at some of the errors that have had an impact in the fansubbing community.

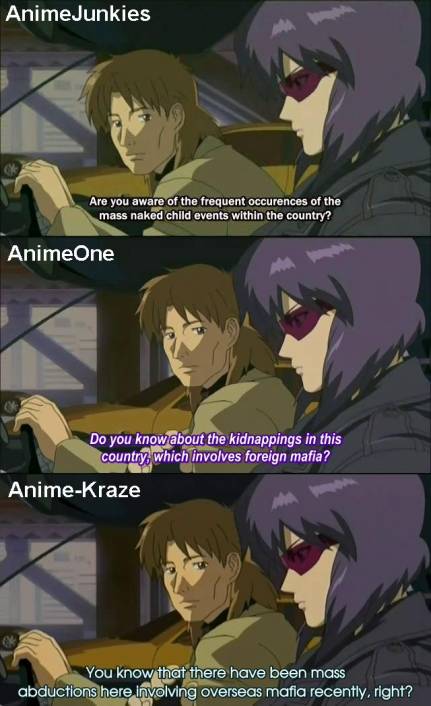

Example 3

Anime: Ghost in the Shell - Stand Alone Complex |

Fansubs: Anime Junkies (AJ), AnimeOne (AOne) and Anime-Kraze (A-K) |

Language: English |

|

The AJ version is certainly one of the most celebrated translation errors in the fansubbing world. In fact, the results that Google retrieves when searching the string "mass naked child events" foreground that this expression is used to refer to Anime Junkies or poor translations. The original meaning of the source language is perfectly rendered in both AOne and A-K versions according to fans, whereas the AJ version has a totally different meaning. The result is a howler probably caused by mishearing the original or by interferences when interpreting the meaning of the source language. The important fact to be underlined here is that the same anime episode or series might be fansubbed more than once by different groups, with translations that vary among themselves.

The following examples illustrate some translation errors that have travelled into Spanish via the English fansubs, which have clearly been used as the pivot translation in the linguistic transfer from the Japanese original.

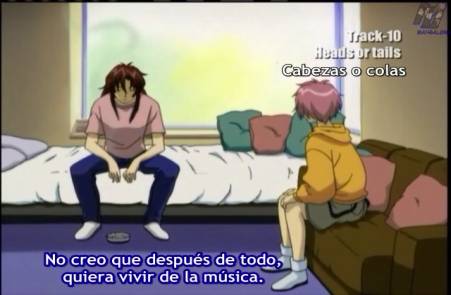

Example 4

Anime: Gravitation |

Fansub: MangaLords (ML) |

Language: Spanish |

|

This is also one of the best-known translation errors among the Spanish fansub community. Here, the translator rendered the title 'Heads or tails' as Cabezas o colas [heads or tails, of an animal] instead of Cara o cruz [head or tails, of a coin]. The fact that the source text is written on the screen and can be seen by the audience makes it rather easy to spot the error.

Example 5

Anime: Tokyo Babylon |

Fansub: Otaku no Power |

Language: Spanish |

|

In this example, the English translation used as source text for the Spanish target text was 'A piece of concrete?', which can be actually seen in the next frame. The Spanish subtitle back translates as 'A piece in particular?'. The translator into Spanish has wrongly assumed that 'concrete' is the same as en concreto [specifically, in particular] when the real Spanish equivalent of the English noun is cemento or hormigon [concrete]. Besides, 'piece' in this context means trozo [piece, bit] in Spanish. The mistake arises from the confusion between the substantive in the original text and the adverb in the translation, as well as from the interference caused by an English false friend. This is one of the pitfalls when the translation cannot be done from the original language and the fansubber has to translate through an intermediary language. Another reason that may explain some of these errors is that the translation was carried out with the help of a machine translation and little human revision. Though these examples are a mere illustration of the problems encountered by fansubbers, it is worth while remembering that if some translation errors are made when translating into English, these tend to be perpetuated when using the English text for the translation into other languages (Díaz Cintas, 2003:80).

6. Conclusions

Fansubbing involves a significant amount of work in which teamwork and co-ordination are essential among the different members of a fansub group. While encoding and timing skills are highly technical and can be learnt in a reasonably short period of time, translation is a much more difficult task that takes longer to master.

Given that fansubbers do the translations for free, one could be forgiven for thinking that - unlike in the professional world - this is a relaxed, stress-free activity. Paradoxically, the ever-increasing standards and release speed that anime fans demand of fansubbers has the effect that many of them get tired very quickly and decide sooner rather than later to quit the fansubbing scene after having worked for a while.

Fansubs share some of the characteristics of professional subtitling, but they are clearly more daring in their formal presentation, taking advantage of the potential offered by digital technology. This new form of Internet subtitling 'by fans for fans' lies at the margins of market imperatives and is far less dogmatic and more creative and individualistic than that which has traditionally been done for other media like the television, the cinema or the DVD. Fansubs are a hybrid resorting to conventions used both in subtitling for the hearing as well as in subtitling for the deaf and the hard-of-hearing. And they also make use of strategies applied in the subtitling of video games. We are witnessing a process of hybridisation where different subtitling approaches and strategies are competing. Subtitling conventions are not set in stone and only time will tell whether these fansub conventions are just a mere fleeting fashion or whether they will spread to other media and become the seed of a new type of subtitling for the digital era.

References

- Andrei, Silvio. 1992. Kinshi. Censure giapponesi. Milan: Immagini Diffusione and La Borsa del Fumetto.

- Animesuki. 2003. "A New Ethical Code for Digital Fansubbing" www.animenewsnetwork.com/feature.php?id=142

- Díaz Cintas, J. 2005. "El subtitulado y los avances tecnologicos", in Merino, R. et al. (eds.) Trasvases culturales: Literatura, cine, traduccion 4. Vitoria: Universidad del Pais Vasco, 155-175.

- Díaz Cintas, J. 2003. Teoria y practica de la subtitulacion: ingles/espanol. Barcelona: Ariel.

- Ferrer Simo, M. R. 2005. "Fansubs y scanlations: la influencia del aficionado en los criterios profesionales". Puentes 6: 27-43.

- Infusion Fansubbing Team. 2003. The Infusion Fansubbing Newbie Guide. www.lolikon.org/guide.html

- Ivarsson, J. 1992. Subtitling for the Media. Stockholm: Transedit.

- Kayahara, M. 2005. "The digital revolution: DVD technology and the possibilities for Audiovisual Translation". The Journal of Specialised Translation 3: 64-74.www.jostrans.org/issue03/articles/kayahara.pdf

-

Macdonald, C. 2003. "Unethical Fansubbers". Anime News Network.com.

www.animenewsnetwork.com/editorial.php?id=43 - Newmark, P. 1988. A textbook of translation. New York: Prentice Hall.

-

Phillips, G. 2003. "Legality of fansubs". Anime News Network.com.

www.animenewsnetwork.com/feature.php?id=144 -

Script Club Discussion Forum. "Regarding FanSub-Sellers…".

www.scriptclub.org/dcforum/DCForumID4/11.html - Stewart, D. 2000. "Poor Relations and Black Sheep in Translation Studies". Target 12(2): 205-228.

Audiovisual sources

- Air TV [Episode 8]. 2005. Ishihara Ritsu. English subtitles by The-Triad.

- DNA^2. 1994. Masazaku Katsura. Spanish subtitles by Tatakae no Fansub.

- Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex [Episode 8]. 2002. Shirow Masamune. English subtitles by AnimeOne, Anime Junkies and Anime-Kraze.

- Gravitation [Episode 10]. 1996. Maki Murakami. Spanish subtitles by MangaLords.

- Kanon. 2002. Key Studio. English subtitles by Anime-Fansubs and AnimeINC Fansubs.

- Tokyo Babylon. 1992. CLAMP. Spanish subtitles by Otaku no Power.