The Good Translator. Emic-cum-etic perspectives on translator competence and expertise

Helle V. Dam1, Aarhus University

Anja K. Vesterager2

Karen K. Zethsen3,

Aarhus University

ABSTRACT

Translator competence and expertise has been the object of much scholarly reflection and research, but studies that address practitioners’ perspectives on the topic remain limited. This article reports on research in which we subjected a theoretical model of translator competence to discussion among translators and elicited their own reflections on the topic, thus combining the scholarly or etic perspective with the emic view of practitioners. Through focus groups, individual interviews and a follow-up workshop, twelve trained and experienced Danish translators circled in what, in their view, it takes to be a good translator. The participants confirmed the relevance of the competence categories of the model up for discussion – Language competence, Thematic and cultural competence, Instrumental competence, Service provision competence and Methodological and strategic competence – but added two distinct capabilities: Prioritisation competence and Overview competence. They also listed various Personal qualities, dispositions and attitudes that the good translator must possess: thoroughness, diligence, curiosity, inquisitiveness, resilience, openness to criticism, knowledge of one’s own competences and limitations, flexibility, adaptability, cooperativeness, empathy, creativity and courage. While the translators recognised the importance of training, they foregrounded experience from practical translation work as a key component of professional competence and a main vector of competence acquisition.

KEYWORDS

Translator competence, translator expertise, emic perspectives, etic perspectives, translation practice, LSP-translation, economic and financial translation.

1. Introduction

What makes a good translator? What kinds of knowledge, skills, competences, abilities and qualities are required not only to translate but to translate well? These questions are as old as translation studies itself. They were addressed already in some of the first publications of the field (e.g. Wilss, 1976) but gained momentum when Holz-Mänttäri (1984) published her seminal book on Translatorisches Handeln, in which she described translation as an expert activity and the translator as an expert. Since then, much research has been conducted to identify what kinds of competences are required to translate and how to distinguish experts from non-experts. Translation scholars in the 21st century are therefore relatively well equipped to provide answers to the opening questions, but we still have some blind angles.

The bulk of research on translator competences and expertise has been conducted within translation process research and cognitive translation studies, hence typically in experimental settings and by means of quantitative methods, such as eye-tracking and keystroke or screen logging (for an overview of extant research, see Risku & Schlager, 2022). As pointed out by Angelone and García (2019, p. 127), the etic perspective — that of researchers, based on models, methods and findings from experiments designed by them — dominates and overshadows the emic perspective of the insiders, in our case that of translators working in the field. We therefore know relatively little about how translators themselves perceive and conceptualise their competence and expertise, and about the relative weight they attribute to the different components.

In this article, we combine the etic perspective with the emic in reporting on a study through which we subjected a theoretical model of translator competence to discussion among practising translators and elicited their reflections on the topic. The etic perspective thus constitutes our point of departure, but the emic viewpoint is our main object of interest. The study was conducted as a side-project to the EU-funded EFFORT-project, Towards a European Framework of Reference for Translation (Hurtado Albir et al., 2023), and because of this project’s affinity with the work of the PACTE group, the study mainly drew on the translator competence model developed by this group, as explained in detail below. The study allowed us to elicit practitioners’ viewpoints on the usefulness of the model but also much more generally on what, in their views, a competent translator needs to know and be able to do.

Theoretically and conceptually, we take a holistic approach, attempting to build a bridge between what is sometimes referred to as (core) competences, i.e. capabilities any (skilled) translator needs to possess and which may be acquired through training, and additional competences or expertise, i.e. capabilities which are developed and honed through professional practice, as explained in the following section.

2. Translator competence and expertise

The concept of translation competence has attracted a lot of scholarly attention over the years. Although there is no unanimously accepted definition of the concept, many translation scholars posit translation competence as a “multicomponential concept” (Göpferich, 2021, p. 89). Thus, it has been described as a “macrocompetence” (e.g. Esfandiari et al., 2015, p. 46) or “supercompetence” (e.g. Pym, 2003, p. 487), which comprises different sub-competences. But this is where the agreement stops. The exact sub-competences that make up translation competence and their interrelationships are subject to controversy (Acioly-Régnier et al., 2015, p. 147; Göpferich, 2021, p. 89). Some scholars argue in favour of minimalist approaches (e.g. Pym, 2003), focusing on translation-specific competences only, while others (e.g. EMT, 2022; Göpferich, 2009; Hurtado Albir, 2015) suggest various multi-componential models that include sub-competences beyond translation-specific ones.

One of these multi-componential models is the well-known competence model developed by the PACTE group. Over the years, this model has been continuously revised in terms of the sub-competences included, their titles and descriptions, but the most recent version, developed in the context of the EFFORT-project to describe the highest competence level, comprises five sub-competences (Hurtado Albir et al., 2023):

Language competence: the ability to apply linguistic knowledge of the source and target languages at all levels (syntactic, lexical, semantic, pragmatic, etc.) in order to translate. Source-text comprehension skills and target-text production skills as well as transfer competence are subsumed under this competence.

Thematic and cultural competence: the ability to apply knowledge of the source and target cultures, knowledge of the world and of specialised areas and specific topics to translate.

Instrumental competence: the ability to use relevant information sources, create documentation resources as well as use and adjust language technology to translate.

Service provision competence: the ability to manage all the aspects related to professional translation practice. This competence entails mastery of, for example, professional ethics, project management and collaboration.

Methodological and strategic competence: the ability to apply appropriate methodology and strategies to produce communicatively adequate translations, solving all types of translation problems and efficiently drawing on the other competences in all stages of the translation process. This competence comprises, inter alia, the ability to plan, execute and evaluate the translation process and the resulting products.

Another influential model is the EMT competence framework, which also consists of five sub-competences (EMT, 2022):

Language and culture: encompasses the linguistic, sociolinguistic, cultural and transcultural knowledge and skills required to translate.

Translation: encompasses all the strategic, methodological and thematic competences needed before, during, and after the actual meaning transfer phase.

Technology: encompasses all the knowledge and skills used to implement current and future technologies in the translation process.

Personal and interpersonal: encompasses all the personal and interpersonal skills that enhance adaptability and employability, i.e. planning, collaboration, and self-monitoring.

Service provision: encompasses all the skills needed to form part of the language service profession, including client awareness and project management.

As is clear from the above, the two models are basically the same type with quite similar sub-competences. However, they emphasise different components. While the model initially developed by the PACTE group foregrounds the thematic and cultural competence and the methodological and strategic competence, the EMT model highlights technology and personal and interpersonal competences as separate components.

Yet other models emphasise other elements. For instance, Göpferich (2009) highlights psycho-motor competence and knowledge of translation norms, Risku (1998) emphasises macro-strategy development and information organisation, Alves and Gonçalves (2007) underline the role of meta-cognition, and Muñoz Martín (2014) highlights adaptive psychophysiological traits.

Olohan (2020), among others, criticises multi-componential models such as these for representing an idealised view of the knowledge and skills required to translate and for reductionistically focusing on the competences that a translation trainee must acquire. By extension, she argues that knowledge cannot merely be stored in the brain for later use but is also generated through practice and shared by practitioners in a particular context. Translators must have acquired the knowledge and skills necessary to be able to translate and know how to “act knowingly” within a specific practice (Olohan, 2020, p. 58). Olohan refers to the latter as “situated capability” (Olohan, 2020, p. 65), arguing that knowing in practice is a prerequisite for being a competent translator. Thus, she advocates focus on the expertise needed as a practising translator with all its facets.

Similar views have been expressed by other translation scholars, who – looking to the field of expertise studies – distinguish between competence and expertise as two separate but interrelated concepts (e.g. Shreve, 2006; Shreve et al., 2018; Tiselius & Hild, 2017). While competence is defined as the “capacities and skills necessary for completing a […] task” (Tiselius & Hild, 2017, p. 426), expertise is described as “consistently superior performance” (Ericsson & Charness, 1997, p. 6) and “the highest level of competence that a person can acquire” (Göpferich, 2021, p. 90). In this perspective, competence is seen as a prerequisite for developing expertise and has been described as “the core, what we need to be professionals”, whereas expertise is “what comes next, an outer circle” (Tiselius, 2013, p. 20). However, it remains unclear “whether expertise is just a higher level of competence, or whether additional skills are needed”, as pointed out by Tiselius and Hild (2017, p. 425). Consequently, some scholars (e.g. Shreve et al., 2018) have proposed that we abandon the notion of competence, arguing that expertise is a more appropriate framework for explaining the progressive development of the translator’s skills. Along the same lines, RETREX (Rethinking Translation Expertise), an ongoing research project based at the University of Vienna (Risku & Schlager, 2022; Schlager & Risku, 2023 and 2024), foregrounds expertise (rather than competence) as the object of study and, much in line with Olohan’s ideas of competence in situated practice, advocates a focus on the social and situated aspects of translators’ expertise.

In this article, we look at both competence, understood as “the core, what we need to be professionals”, and expertise as that which “comes next, an outer circle”, to use Tiselius’ words again. We look at the capabilities any translator needs to possess, and which may indeed be acquired through training, and capabilities which may not be acquired until experience as a practising translator is gained. In many cases, it is in fact impossible to distinguish between the bare essentials, that which some scholars refer to as competence, and the extra layer of expertise that may come with practice. As our empirical study indeed shows and as we shall see further down, the very same abilities may in fact be acquired through training but developed through practice, and the boundaries between the two are fuzzy and porous.

Following the terminology used in the project the study originally formed part of – the EFFORT-project – we tend to use the term competence(s) in this article. Not solely to denote core skills or to exclude skills that are acquired through practice but as a cover term along the lines proposed by Schäffner and Adab (2000, p. x), who describe competence as “a superordinate, a cover term and summative concept for the overall performance ability which seems so difficult to define”. The title of this article – The Good Translator – embraces both competence and expertise, under any definition, and mirrors both our holistic approach to the topic under scrutiny and the emic focus of the article. In our discussions with practising translators, this was often how the concepts of translator competence and expertise were phrased: as that which makes a good translator.

3. Methodology

Data for the study were mainly collected through interviews with practising translators. Two interview sessions were conducted using the focus-group method and two were organised as individual interviews. The focus groups, a participant-centred method that relies on group interaction among peers, were well-suited to collect data on group views, understandings and norms, whereas the individual interviews allowed us to elicit in-depth data on the perspectives of individual practitioners.

Complementary data were collected in a dissemination event in which we presented the preliminary results of the study and invited participants to discuss these and share any additional reflections they might have on the topic of being a good translator. Among the participants were eight translators whose input serves as an additional source of data for the research. Table 1 provides an overview of the data sources.

| Interview sessions | Participants |

|---|---|

| Focus group 1 (FG-1) | three agency translators |

| Focus group 2 (FG-2) | three company translators (bank) |

| Individual interview 1 (II-1) | one company translator (law firm) |

| Individual interview 2 (II-2) | one institutional translator (EU) |

| Dissemination event | Participants |

| Posters (DE-P) and Discussions (DE-D) | eight translators (diverse work contexts) |

Table 1. Overview of data sources

We use the label ‘agency translator’ here to refer to translators who are employed in a translation agency. By ‘company translators’ we mean translators employed in a company whose core product or service is not translation. In our case, the companies were a bank (focus group 2) and a law firm (individual interview 1). The institutional translator (individual interview 2) was employed in the EU. The participants in the dissemination event had a range of different job profiles, as described in the following section.

3.1 Participants

The professional profiles of the eight interviewees were similar. Their educational background was an MA in specialised translation in all cases. Their experience with professional translation ranged from 9 to 34 years, with an average of 21.3 years. They were, in other words, both trained and highly experienced translators, hence in a vantage position to talk about both the formal translation competences they had acquired through training and the skills and knowledge they had developed through professional experience: the “situated capability” that enables them to “act knowingly” within their specific area of practice, to use Olohan’s words again.

Their work contexts differed, as we saw in section 3, but they were all employed in businesses or institutions where specialised, non-fiction translation dominates: economic, financial, technical, legal, etc. All eight were specialists in economic and financial translation and regularly translated texts within that domain, but all of them had experience from other LSP-areas too. In fact, during the interviews the translators repeatedly pointed out that in actual fact most texts are hybrid and exhibit features from various domains (legal, economic, etc.), and also that the nature of the competences required are the same irrespective of whether the specialisation is economic or, say, legal or technical. Thus, they clearly felt equipped to talk about what it means to be a competent translator across the traditional domains of LSP-translation.

Five of the translators were women, and three were men. Each focus group had one male and two female members. The study was limited to the Danish translation market, the Danish translation departments of the European Union’s Institutions included, and the L1 of all interviewees was Danish. All eight were staff-employed at the time of data collection, but they all had experience from other types of employment, including as self-employed or freelance translators.

Among the eight translators who participated in the dissemination event, four had also participated in the interviews and four had not. The latter four were also trained and experienced translators who had worked on the Danish market, the EU included, for many years (between 13 and 32 years, with an average of 21.5 years of experience) with various kinds of specialisation or as generalists. Three were women, one was a man. Of the additional four translators who participated in the dissemination event, two were freelancers, whereas two were employed as staff translators in the EU at the time of data collection; they all had previous experience as freelance translators.

Among them, the twelve translators who contributed data to the study thus had experience with translation work in a variety of contexts and conditions.

3.2 Procedure

The interview data were collected in April and May 2022. The focus groups were conducted at the translators’ workplaces, whereas one individual interview took place at the authors’ university, and the other was conducted online. For both focus groups and individual interviews, two researchers (among the authors) were present: a moderator/interviewer who guided the conversations and an observer who took notes and occasionally asked complementary questions.

Three days before each interview session (focus group or individual interview), the participants received a document outlining the main characteristics of translation at the highest competence level and, by analogy, of being a translator at that level, within the area of specialisation they shared: economic/financial translation. The document was drawn up on the basis of a review of the literature, and it contained keywords revolving around four main topics: the tasks of translators within their area of expertise; the genres they translate; the resources and tools they use; and the competences they need, following a template generated in the context of the EFFORT-project. Apart from the keywords identified in the literature, each topic was accompanied by questions for the participants to reflect on before their interview session, inviting them to consider critically the contents of the document.

The keywords given on the central topic of competences mirrored those of the PACTE competence model as outlined in section 2, organised under the five subheadings of Language, Thematic and cultural, Instrumental, Service provision and Methodological and strategic competences.

Keywords and questions served merely as reflection triggers, and we did not go through all of them during the interviews, which revolved around the headlines of each topic in a fairly open manner. Conversations on the topic of tasks, for example, were initiated by the prompt: ‘on the topic of tasks: please tell us about the tasks you are currently engaged in’. The participants were informed of the procedure in advance. They were also informed that the main focus of the interviews would be the topics of tasks and, notably, competences, the rationale being that the latter was our focus of interest, whereas the former would anchor the discussions in the participants’ everyday practice as translators. The additional topics of genres they translate and resources/tools they use served the same purpose.

The duration of the focus groups and individual interviews was between one hour and ten minutes and one hour and thirty minutes.

The complementary data-collection session – the dissemination event – took place in June 2023 and lasted two hours. After we had presented the results of our preliminary analyses of translator competence, the participants were invited to write down five to ten keywords or key statements which, in their view, would best describe ‘the good translator’. Keywords and key statements were captured on posters, which were then discussed in groups along with the results we had presented.

All data-collection sessions (focus groups, individual interviews, dissemination event) were conducted in Danish. The data extracts that accompany the analyses in section 4 were translated into English by the authors.

3.3 Analyses

The analyses, then, relied on a variety of complementary data sources: audio-recordings of the interview sessions and transcripts of these; observer’s notes from the interviews and from the discussions during the dissemination event; and the keyword posters produced by the translators during this event.

Thematic analysis was used to identify and group all statements about translator competence: all the knowledge, skills, qualifications, abilities and attitudes that trained and experienced translators report they mobilise to perform well. The analyses relied on both deduction and induction. Some themes were established beforehand based on the keywords included in the document we shared with the interviewed translators. The inductively generated themes are based exclusively on information that the translators added during interviews and discussions, both when they addressed the topic of translation competences directly and when they talked about other topics.

The analyses were conducted manually and in several iterations by the authors.

4. Results

In this section, we present the findings of the study, showing how the highly trained and experienced translators in our study talk about what it takes to be a competent or expert translator – or, in their own words: what it takes to be a good translator. As one of our interviewees noted when discussing translator competence: “Anyone can become a translator but not necessarily a good translator”.

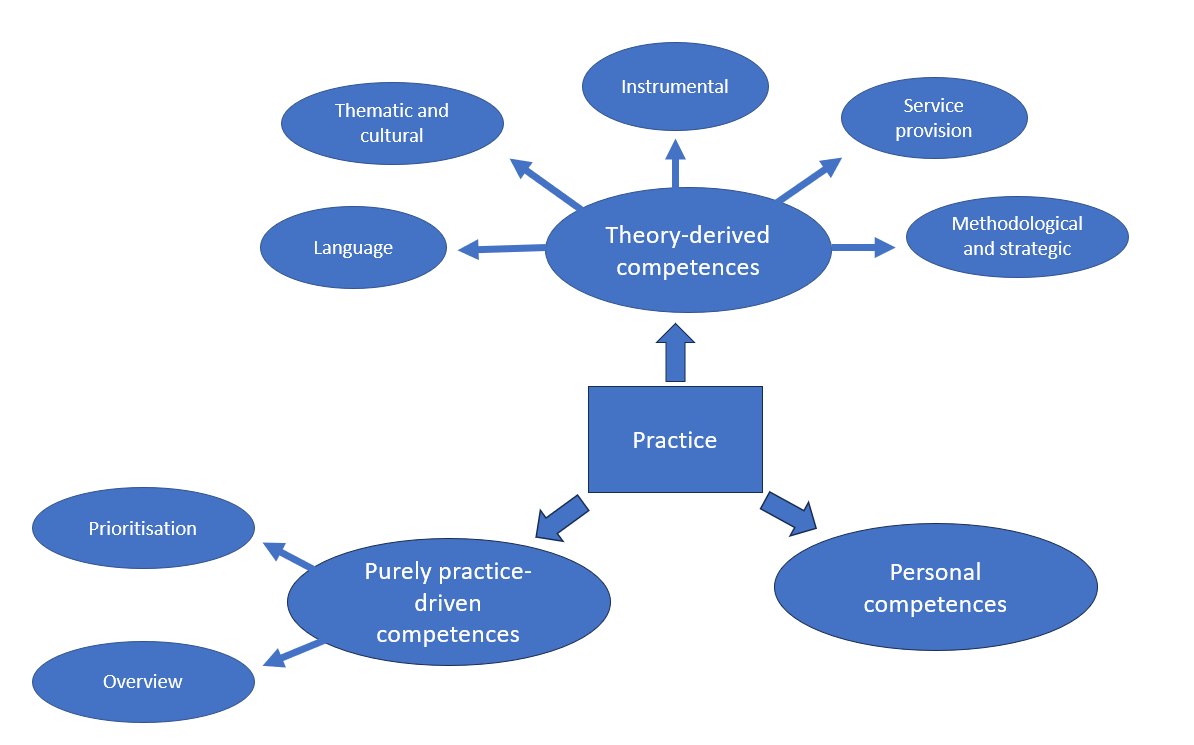

The many (sub-)competences the translators discussed and proposed may be subsumed under three headings: theory-derived competences, purely practice-driven competences, and personal competences, as explained in the following three subsections.

The source of the data extracts we present below to illustrate the categories is indicated by means of abbreviations: FG-1 for Focus Group 1 and FG-2 for Focus Group 2; II-1 for Individual Interview 1 and II-2 for Individual Interview 2; DE-P for Dissemination Event: Poster; DE-D for Dissemination Event: Discussion.

4.1. Theory-derived competences

The analyses soon showed a broad consensus among the translators on the relevance of the five sub-competences we had presented to them in advance. Because these competences are derived from a theoretical model, in this case the PACTE competence model, we discuss these under the heading of theory-derived competences. This label is chosen exclusively to denote their origin in theory and should not be mistaken to imply that they may only be acquired through theory-based learning. Most of the so-called theory-derived competences may indeed be achieved through training, but our conversations with the translators leave no doubt that they are developed and refined through practice.

Mirroring the sub-competences of the PACTE model described in section 2, the theory-derived competences we discuss include: Language competence; Thematic and cultural competence; Instrumental competence; Service provision competence; and Methodological and strategic competence. It should be stressed that the participants were generally not familiar with these labels. Apart from the more self-explanatory names (Language competence, for example), most of them required some explanation on our part. Once explained, however, the translators immediately recognised the skills behind the labels and confirmed their importance in most cases. In the following subsections, we present the translators’ discussions of each of the five theory-derived sub-competences.

4.1.1. Language competence

Across the board, the participants agree that, even though we may tend to forget or ignore it, Language competence is the most central competence for the good translator. It is described as “the basis of it all” (FG-2) and “the prerequisite of it all” (DE-D). The translators distinguish between source language competence, for which they require “100% understanding” (DE-P), and target language competence, which to them involves “highly nuanced mastery” (DE-P).

Source language competence, then, is described as the ability to understand the source text, but it goes beyond that. As one participant says, the good translator is able to “get into the heads of people and understand what they are in fact trying to communicate” (FG-1). In the process of making sense of the source text and grasping the intended meaning, text analytical competences are indispensable, as emphasised by several participants.

When discussing target language competence, the participants generally talk about being able to produce a translation that reads fluently and draws on all the facets of the target language. In the words of one participant, the good translator is in fact “completely crazy about expressing themselves adequately” in the target language. Another participant argues that target language competence is what allows the good translator to compensate, in the target text, for potential shortcomings of the source text (which they are not afraid to correct and improve). Several of the translators foreground the importance of mastering the target language to a very high level, above and beyond all other competences.

Across the board, the participants argue that the translator’s language competence is developed and refined with practice. For example, one translator says that experience enables them to “see how things are connected” (FG-1) and make sense of the source text. Another participant mentions that translators’ transfer skills develop gradually, and that fast and efficient transition from source to target language is “difficult to learn unless you get hands-on practical experience” (II-1). She continues, arguing that increasing experience makes for a higher degree of automaticity:

Example 1 (II-1)

And it does come with experience […] when you have many years of experience, those phrases become routine. You just churn them out, I would say.

4.1.2. Thematic and cultural competence

The Cultural competence was only touched upon briefly by the translators. They recognised it as part of the good translator’s repertoire but did not pay much attention to it in their discussions, perhaps because of their backgrounds as LSP translators. The Thematic competence, on the other hand and not surprisingly, was foregrounded as being highly central.

In their discussions of Thematic competence, the translators talk about “core knowledge” (II-2), which to them means knowledge of the content or subject matter and the terminology associated with it, as being crucial. In addition, the translator must know how the topic of the translation fits into a larger context. In the words of one participant, the translator must know which “universe” (II-2) it belongs to in order to make the right decisions.

Furthermore, several of the participants mention that general knowledge is important. In the words of the participants, the good translator must acquire “knowledge about the world” (FG-1), possess “culture générale” (DE-P), be “interested in the world around us” (DE-P) and “keep abreast of what is happening around you” (DE-P).

The participants emphasise that Thematic competence (like Language competence) is developed and perfected with practice. For instance, one participant argues that with experience comes the ability to identify and resolve problems and inconsistencies of the source text, drawing on one’s repertoire of specialised knowledge:

Example 2 (II-2)

But using one’s core knowledge, my economic knowledge I mean, to solve problems of course but also to see that ‘this is complete nonsense which does not make any sense’ and then to get it to make sense. That’s good fun!

According to another participant, experience within a domain helps “speed up” (II-1) the translation process.

4.1.3. Instrumental competence

The translators also unanimously confirm the importance of the Instrumental competence (although they were not familiar with the label, and clarification was needed).

The participants’ discussions of this competence mainly centre on the need for translators to acquire appropriate information search strategies. According to the participants, the good translator has a wide range of information sources at their disposal and knows where and how to search for the information needed. They list a large number of information sources (e.g. parallel texts, corpora and background information such as a client’s website or legislation underlying the topic of the translation task). They draw extensively on digital resources and technological tools (e.g. terminology databases, translation memories and machine translation) and emphasise that IT skills and technological competences are a sine qua non in modern-day translation (though several express resentment towards machine translation and post-editing tasks). Most of the resources they mention are sophisticated and state-of-art, but they are not shy about admitting that they still use “old-fashioned” (II-1) dictionaries quite extensively, and that Google is a highly popular search tool.

Technological resources are no doubt important, but the translators also stress the importance of human information sources: they report drawing on non-translating experts of various kinds, but the perhaps most widely used and appreciated resource is their translator colleagues (cf. section 4.1.4).

Across the board, the participants state that, as the translator gains more experience, information searches are carried out more efficiently and quickly and with less effort on the translator’s part, as something that “has become routine, almost a reflex” (II-2).

4.1.4. Service provision competence

Initially, the interview and focus-group participants were uncertain about the Service provision competence, and some asked for a clarification. After coming to an understanding of this competence, they all state that it is mainly acquired in the course of the translator’s post-university career.

In their discussions, the translators talk about the necessity of acquiring knowledge of their clients and, particularly in the case of institutional and company translators, of the organisation they are employed in. These translators explain how they need to know internal rules, policies, procedures and people to be able to provide the best possible service to their in-house clients and commissioners. The participants also mention ethical considerations as important, and the bank translators (FG-2), for example, foreground confidentiality issues involved in storing information in the cloud.

Collaboration is a salient topic in the discussions, and the translators foreground the necessity of possessing collaborative skills or a “collaborative mindset” (DE-P). First, they discuss the importance of collaborating with the client or text producer and being able to “discuss back and forth with them” (II-1) and to “spar with them” (FG-2). More specifically, they talk about contacting the client to clarify potential doubts and about sometimes having to negotiate deadlines with them. They also collaborate with clients to resolve terminological inconsistencies, and, in this context, especially the agency translators talk about “advising the client” (FG-1) and “helping the client” (FG-1) ensure terminological consistency. The bank translators explain how they sometimes engage in joint text production processes with their in-house clients and add that in this way the translators often “take co-responsibility for the texts we translate” (FG-2).

Second, the participants mention collaborating with colleagues in a narrow sense, that is, fellow in-house translators. Especially in the focus groups, the translators talk at length about how they draw on each other’s competences and expertise, and one participant refers to colleagues as being “lifelines” (FG-1).

Third, they talk about collaborating with external parties, such as authorities and freelance translators. The EU translator, for example, explains how they sometimes work with the Danish authorities to create terminology collaboratively. On the topic of freelancers, the bank translators find it “refreshing” (FG-2) to work with freelancers because they sometimes contribute with different terminological suggestions, which are then discussed to reach a mutual agreement.

In addition to collaborative skills, the participants foreground project management, arguing that translators often work on “large projects that need to be managed” (DE-D). But managing incoming projects, no matter their size, is described as an everyday task for translators. As one company translator explains:

Example 3 (II-1)

So you communicate with the commissioner and find out ‘what is it for […], what will it be used for, and […] when?’ You file it and take a look ‘who can do this? Who has perhaps done something similar recently, who knows most about this subject or usually works with it? Or who has the time?’

Although project management is foregrounded as an essential part of translation, it is not always a favourite task. The same participant adds that while she acknowledges the importance of project management, sometimes “I just look forward to delving in” (II-1), referring to the core task of translating.

4.1.5. Methodological and strategic competence

The participants were initially unsure about the Methodological and strategic competence and asked for clarification. Once clarified, the participants confirm across the board that this competence is central for the good translator and that, like the Service provision competence, it is mainly acquired through practical experience.

The participants foreground being able to plan and carry out a translation task, i.e. keeping an overview of the task and its various phases. As explained by one participant:

Example 4 (II-2)

Well, how do you manage a 150-page task, knowing that there will be at least two new versions and that it has to be completed in two weeks? Obviously, it requires some planning […] ‘How do I go about it, where do I start?’ It can be on these concepts, or maybe something needs to be clarified with external authorities and you have to contact them because otherwise you risk not having time in the end to cooperate with them.

The participants emphasise the importance of time management as a key component in planning and monitoring the translation process, and they also foreground the need to monitor their own performance. In a similar vein, revision and the continuous feedback processes that are part and parcel of contemporary translation projects was a recurrent theme in the discussions. According to the participants, high-level translators must be able to assess both their own work and the work of others, hence be capable of providing and receiving constructive criticism.

In addition, the translators highlight target group adaptation, which to them involves being able to identify with the receiver of the translated text (cf. sections 4.1.1 and 4.3) to make, for example, terminological decisions that suit the target group. While the participants generally agree that target group adaptation is important, they stress that the type and degree of adaptation depends on the translation context. As they say, the translator must decide, in each situation, whether to adapt and, if so, how to adapt the translation to the target group.

4.2. Purely practice-driven competences

Apart from the so-called theory-derived competences discussed in section 4.1, the participants made unsolicited comments through which they circled in two additional abilities, beyond the competence keywords we used as prompts. According to the translators, these additional competences are not, and cannot be, acquired during training but only through practical experience. Hence, we discuss these under the label of purely practice-driven competences.

The translators’ immediate reaction to both the Service provision competence and the Methodological and strategic competence, discussed above, was also that these are acquired exclusively through practice, but when prompted a bit, they agreed that some of the components – such as professional ethics and translation strategies – are indeed taught in the context of translator training. The competences we categorise as ‘purely practice-driven’ can only be acquired through practice, according to the translators. What is more, these competences are clearly seen by the translators as decisive for their professionalism and expertise as practising translators. They lie at the heart of their capability not only of knowing and acting in certain ways but of “acting knowingly”, to use Olohan’s words again.

The purely practice-driven competences comprise Prioritisation competence and Overview competence, as described in the following subsections.

4.2.1. Prioritisation competence

The first practice-driven competence pointed to by the participants is the ability to prioritise. The participants repeatedly emphasise that translators are under much pressure to deliver quality translations under tight deadlines and, therefore, have to be able to “set extremely tough priorities and cut to the bone” (DE-P). For instance, one participant states that, in each translation situation, the translator must be able to decide which tasks can be resolved quickly and which require more attention to detail:

Example 5 (FG-1)

This translation, from a really good freelancer that you have cooperated with for many years and know without doubt delivers quality, you can run through quickly and then concentrate on a more demanding task.

In the same vein, another translator talks about deciding whether it is “a task which should be sprinkled with fairy dust, or should it be just so that the client is satisfied” (DE-D).

Sometimes, the client (or brief) helps the translator prioritise by emphasising the importance of some aspects over others. In the words of one participant: “well, [they] say themselves that they prefer getting it out fast and then it doesn’t matter if there is a typo or some other error” (FG-2). But more often than not, the translator must make autonomous decisions about how to prioritise when working under tight deadlines, as shown in the previous examples.

The translators consistently emphasise the need to be productive, sometimes at the expense of quality:

Example 6 (FG-2)

A good translator can also step back from the text and see it in another light […]. But once again time is a factor in determining whether it is possible or not.

From a theoretical (etic) viewpoint, Prioritisation competence, inherently strategic in nature, could easily be subsumed under the Methodological and strategic sub-competence. In line with the emic focus we have adopted in this paper, however, we have chosen to follow the participants’ insistence of its separate status.

4.2.2. Overview competence

The data also pointed to another practice-driven competence, which we refer to as overview competence, that is the ability to “look up from” (FG-1) the task at hand and put it in context with associated translation tasks. For instance, one of the bank translators talks about sometimes having to revise the terminology of previous translations to ensure terminological consistency, emphasising that translation is a dynamic process:

Example 7 (FG-2)

If a term is changed, we have to go back three documents because we called it something else then based on different information.

The agency translators specifically mention the importance of keeping an overview of how one translation task fits into a larger context of associated projects:

Example 8 (FG-1)

Having an overview and being able to see ‘well, if this is how it’s phrased in the annual report, and it’s cited almost directly in the CSR-report, then [the two must be aligned]’. That’s also where the counselling comes in because often […] the client has no awareness of these things.

Another participant in the same focus group emphasises the importance of being able to anticipate future associated tasks in connection with incoming tasks:

Example 9 (FG-1)

My hobbyhorse is that if the client wants the annual report translated you should always ask if other associated documents will also need to be translated. Often it’s not just the annual report […], the CEO may need a PowerPoint presentation, there are press releases, there are all sorts of things in connection with the publication of an annual report, and it’s a great advantage if it’s the same translator who does it all.

Such anticipation abilities allow the agency to be proactive: to allocate translator resources adequately, now and in future, with the ultimate aim of ensuring both work efficiency and output consistency, i.e. productivity and quality. Example 4 (section 4.1.5) points to a similar proactiveness, only in connection with one and the same translation task. That is, example 4 reveals task-internal proactiveness, whereas examples 8-9 illustrate task-external proactiveness.

The category overlaps are evident: example 4 illustrates a thorough planning process applied to one and the same task (i.e. Methodological and strategic competence), which in fact resembles the planning revealed by example 9, but here connected with several tasks (categorised as Overview competence), itself a good example of competent project management, a component of the Service provision competence. We discuss these overlaps in section 5.

4.3. Personal competences

In addition to the so-called theory-derived competences and purely practice-driven competences described in the previous sections, the participants list a large number of personal competences that characterise the good translator. Some of these competences have seemingly developed through long-standing immersion in translation, whereas others are presented more as innate qualities, rather like personality traits. The examples in this section mainly derive from the data collected at the dissemination event, during which we did indeed invite the translators to describe and discuss what characterises ‘the good translator’, but personal competences and traits cropped up time and again during the interviews and focus-group sessions too.

According to the participants, the good translator has a good sense of language and is detail-oriented, thorough, and diligent. In the words of the participants, the good translator “makes an effort” (II-2), “nurses the text” (FG-2) and “is a language nerd” (II-1)”. The good translator is also curious and inquisitive and has a profound and broad interest in the world around us and preferably also in the topics they translate.

In addition, the good translator is patient and resilient, qualities that are needed to cope with the many iterations and revisions of the same text, source as well as target. Feedback from revisers and clients commands openness to criticism, justified or not. By association, the good translator is reflective, hence capable of reflecting critically on their own competences and limitations.

The modern translator must be flexible and adaptable in response to industry dynamics and the growing complexity of the field. In particular, today’s translator is a multitasker, able to competently handle various tasks at the same time in order to meet increasing demands for productivity, efficiency and timeliness. Translators must of course also be sociable, co-operative and, as previously described, possess a “collaborative mindset” (DE-P) as translation requires collaboration with a wide range of actors.

The good translator is also characterised as thoughtful and empathetic, since reflections concerning target group adaptation is a central part of any translation task and because the good translator must be able to “get into the head” (FG-1) of the source text producer (cf. section 4.1.1).

Finally, the good translator is creative and not afraid to depart from the source text when translating. In the words of the participants, the good translator “pimps it a bit”, “pimps it up”, “tries something new”, “makes it a bit sexy” (FG-1) and “joggles the language” (II-2). In this connection, one participant talks about the good translator as being courageous, which is something that comes with experience:

Example 10 (II-2)

Well, I’m of the opinion that it’s good to be a bit courageous, if I can use that expression, in your choices, right […] Courageous is not something you are from day one […], it comes with time, yes, that’s what I think.

A similar point regarding courage is made by another participant who argues that “you become more daring with experience” (II-1).

Interestingly, the translators’ discussions of personal qualities and attitudes show that they operate a continuum of competences which develop with experience and over time. In some cases, it is possible to discern a three-step process: first, they acquire formal or core competences, most likely at university; next, they hone them through professional practice, a process that strips their abilities of any formal or theoretical anchorage; finally, they turn what they have learnt and used in practice into personality traits or features of identity. The example of language competence is a good illustration: first, they learn languages at university, a process they readily describe as acquisition of language competence; with experience, they develop this competence and acquire a (slightly mysterious) sense of language; finally, they describe themselves as language nerds, a frequent self-characterisation label in our data.

Sometimes, the identity-formation process only has two steps: at university, they learn information search skills, as they say (Instrumental competence is not a label they use), which time and life in translation readily turns into a general quality of curiosity, interest and inquisitiveness. Moreover, the often-mentioned ability to adapt a source text to a specific target group (Methodological and strategic competence) is translated into a general quality of empathy. In the words of the participants, the good translator is a person who is “empathetic” (DE-P), “can put themselves in the place of others” (DE-P) and is able to “see things through the eyes of others” (FG-2). In any case, they literally turn can do into is.

Interestingly, a recent study among translation practitioners has identified some of the very same personal competences or “soft skills” (Schlager & Risku, 2024, pp. 10-11) as those pinpointed by the participants in the current study.

5. Discussion and conclusions

In this article, we have analysed the many sub-competences discussed and proposed by the translators in our sample under three headings: theory-derived competences, purely practice-driven competences and personal competences.

The analysis of the first group of theory-derived competences showed, among other things, a strong interrelationship between translator training and practical experience in the acquisition and development of translator competence. The translators agreed that the foundations of Language, Thematic/cultural and Instrumental competences are laid in the course of training and developed and perfected through professional practice. They found that Service provision and Methodological and strategic competences are predominantly acquired through practice but, after some discussion, recognised that elements of both these competences could in fact be integrated into training.

According to the translators, however, some competences can only be acquired through practice, as discussed under the heading of purely practice-driven competences. In their view, it is through sustained practice that the translator learns how to prioritise tasks and resources in a busy workday and to keep an overview of and contextualise translation tasks, connecting them to related tasks, past and future.

Interestingly, the analyses also showed consensus on a number of personal dispositions, attitudes and qualities that characterise the good translator, discussed under the heading of personal competences. Some were presented as innate traits, but the general consensus on the good translator’s personal qualities suggests that many are the result of long-standing immersion in translation practice.

The translators in this study clearly viewed practical experience as the main vector of competence acquisition. An extract from one of the focus groups’ discussions of the interplay between training and practice is telling of the importance the translators attribute to practical experience:

Example 11 (FG-1)

For sure there are competences that can be acquired, at university for example, but it’s a bit like driving. That is, you get your driving license and then you actually learn how to drive a car. In much the same way, it’s the experience you gain over the years that makes you a good economic translator.

One of the participants in the dissemination event even suggested that “experience” (DE-P) is an inherent characteristic of the good translator. This emphasis on experience should not be taken to imply that the translators do not value formal education, however: they clearly appreciate their “driving license”, but when they converse freely about their skills and competences, experience from practice repeatedly crops up as a particularly important factor.

Figure 1 provides an overview of the competence categories that emerged from the study, with practice as the central component that connects the three main competence areas.

Figure 1. Overview of the competences of The Good Translator

The results of the study provide emic support to the main tenets of the PACTE model, the point of departure of the study. Not all aspects of the model could be covered in our conversations with the translators, but they confirmed the validity of its five sub-competences overall and, when asked directly during the dissemination event, the participants agreed that the model provides an exhaustive account of what it takes to be a competent translator (“yes, it covers everything”, DE-D). Our analysis of the translators’ discourses did identify additional competences, not covered by the model. From an etic perspective, however, the so-called purely practice-driven components suggested by the translators can easily be subsumed under the Methodological and strategic or Service provision competences, broadly defined as they are. What the PACTE model does not cover is the many personal competences the translators mentioned as crucial.

In this respect, the EMT model matches translator perceptions more accurately. Its emphasis on (inter-)personal competences is very much in line with the practitioner views that emerged from the study. Similarly, the importance of both collaboration and technology, hence the need for collaborative and technology skills, highlighted by the EMT model emerged as salient themes in our data too.

Incidentally, the analyses suggest that Olohan’s criticism of multi-componential competence models is not entirely justified. As described in section 2, she criticises such models for being reductionistic and strongly linked to curriculum design and what is needed to be a competent translation student. However, most of these models, and certainly the model we have looked at in this study, do comprise both skills that are taught in the context of translator training programs and skills that are acquired and/or perfected through practice, as our conversations with the translators consistently showed. In fact, the various sub-competences as well as the different competence categories we have suggested here – theory-derived, purely practice-driven and personal – are intertwined to an extent that prevents us from drawing clear boundaries between them. This finding supports a unified approach to the topic of translators’ performance abilities such as that advocated by translation scholars who have abandoned the distinction between ‘competence’ and ‘expertise’, as explained in section 2.

To honour the emic perspective, we shall conclude this article by giving the floor to the translators, relating what, in their words rather than in theoretical terms, makes a good translator. According to the translators who participated in the study, The Good Translator:

Has an excellent command of her working languages, the target language in particular, and is able to switch between them rapidly and efficiently. She has analytical skills, is empathetic and has the ability to “get into the heads of” source text producers and “see how things are connected” as well as understand the needs of and, in fact, “put herself in the place of” the target group.

Has a solid knowledge of the topics she translates, the larger domains they are anchored in and a high level of general knowledge. In fact, she possesses “culture générale” and, as a person, she is curious, inquisitive and interested in the world around us.

Is able to compensate for any gaps in her linguistic or background knowledge through efficient information search strategies. She possesses deep knowledge of the tools and resources at her avail and knows how to use them to produce fast and efficient results.

Has a high awareness of her clients (commissioners as well as end-clients), the institutional context she works in, and professional ethics.

Is an efficient project and time manager, has excellent collaborative skills and works seamlessly with colleagues, stakeholders and resource persons of all kinds. She is also able to advise on matters related to texts and translation and can take on the role of co-producer of source and target texts.

Can efficiently plan, carry out, monitor and evaluate translation tasks, her own as well as those of others. She is capable of making the right decisions according to the context (text type, genre, commissioner, target group, etc.), prioritising some tasks over others and some aspects of a task over others. In general, she is capable of striking the right balance between quality and productivity.

Possesses sufficient overview of the situation to be relevantly proactive and reactive, i.e. to anticipate what is coming and to go back and correct past tasks when the need arises.

Has a particular set of personal qualities, attitudes and traits: apart from possessing empathy, curiosity and a collaborative mindset, she is thorough and diligent, capable of critical reflection, resilient, flexible and able to multitask. She is also courageous and creative, and a profound sense of language is among her most important qualities.

But above all, The Good Translator has experience from translation practice.

Acknowledgements

This research was conducted as a side-project to the EFFORT-project, Towards a European Framework of Reference for Translation, supported by the European Union, grant number 2020-1-ES01-KA203-082579. We are grateful to our project partners: A. Hurtado Albir, P. Rodríguez-Inés, F. Prieto Ramos, R. Dimitru, M.M. Haro Soler, E. Huertas Barros, M. Kujamäki, A. Kuznik, N. Pokorn, G.-W. van Egdom, M.C. Acuyo, S. Ciobanu, O. Cogeanu-Haraga, T. Ghiviriga, S. González Cruz, K. Gostkowska, N. Ilhami, T. Mikolic Juznic, M. Panchón, S. Paolucci, N. Paprocka, S. Parra, A. Pisanski Peterlin, R. Solová, G. Soriano Barabino, J. Umer Kljun, J. Vine, M. Walczynski and C. Way.

References

Acioly-Régnier, N. M., Koroleva, D. B., Mikhaleva, L. V., & Régnier, J. (2015). Translation competence as a complex multidimensional aspect. Procedia – Social and Behavioural Sciences 192(44), 142-148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.08.035

Alves, F., & Gonçalves, J. L. (2007). Modelling translator’s competence: Relevance and expertise under scrutiny. In Y. Gambier, M. Shlesinger, and R. Stolze (Eds.), Doubts and directions in translation studies: Selected contributions from the EST Congress, Lisbon 2004 (pp 41-55). John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Angelone, E., & García, A. M. (2019). Expertise acquisition through deliberate practice. Gauging perceptions and behaviors of translators and project managers. In H. Risku, R. Rogl, & J. Milosevic (Eds.), Translation practice in the field: Current research on socio-cognitive processes (pp. 123-160). John Benjamins Publishing Company.

EMT (2022). Competence framework 2022. European Commission. https://commission.europa.eu/system/files/2022-11/emt_competence_fwk_2022_en.pdf

Ericsson, K. A., & Charness, N. (1997). Cognitive and developmental factors in expert performance. In P. J. Feltovic, K. M. Ford, & R. R. Hoffmann (Eds.), Expertise in context: Human and machine (pp. 3-41). AAAI Press/MIT Press.

Esfandiari, M. R., Sepora, T., & Mahadi, T. (2015). Translation competence: Aging towards modern views. Procedia – Social and Behavioural Sciences 192(44), 44-53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.06.007

Göpferich, S. (2009). Towards a model of translation competence and its acquisition: The longitudinal study ‘TransComp’. In S. Göpferich, A. L. Jakobsen, & I. M. Mees (Eds.), Behind the mind: Methods. models and results in translation process research (pp. 11-37). Samfundslitteratur.

Göpferich, S. (2021). Competence, translation. In M. Baker, & G. Saldanha (Eds.), Routledge encyclopedia of translation studies (pp. 89-95). Routledge.

Holz-Mänttäri, J. (1984). Translatorisches Handeln: Theorie und Metode. Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia.

Hurtado Albir, A. (2015). The acquisition of translation competence. Competences, tasks, and assessment in translator training. Meta 60(2), 256-280. https://doi.org/10.7202/1032857ar

Hurtado Albir, A., Rodríguez-Inés, P., Prieto Ramos, F., Dam, H. V., Dimitriu, R., Haro Soler, M. M., Huertas Barros, E., Kujamäki, M., Kuźnik, A., Pokorn, N., van Egdom, G. M. W., Ciobanu, S., Cogeanu-Haraga, O., Ghivirigă, T., González Cruz, S., Gostkowska, K., Pisanski Peterlin, A., Vesterager, A. K., Vine, J., Walczyński, M., & Zethsen, K. K. (2023). Common European framework of reference for translation – Competence level C (specialist translator): A proposal by the EFFORT project. https://www.effortproject.eu/

Muñoz Martín, R. (2014). Situating translation expertise: A review with a sketch of a construct. In J. W. Schwieter, & A. Ferreira (Eds.), The development of translation competence: Theories and methodologies from psycholinguistics and cognitive science (pp. 2-56). Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Olohan, M. (2020). Translation and practice theory (1st edition). Routledge.

Pym, A. (2003). Redefining translation competence in an electronic age. In defense of a minimalist approach. Meta, 48(4), 481-497. https://doi.org/10.7202/008533ar

Risku, H. (1998). Translatorische Kompetenz: Kognitive Grundlagen des Übersetzens als Expertentätigkeit. Stauffenburg.

Risku, H., & Schlager, D. (2022). Epistemologies of translation expertise: Notions in research and praxis. In A. Marín García, & S. Halverson (Eds), Contesting epistemologies in cognitive translation and interpreting studies (pp.11-31). Routledge.

Schäffner, C., & Adab, B. (2000). Developing translation competence. John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Schlager, D., & Risku, H. (2023). Contextualising translation expertise: Lived practice and social construction. Translation, Cognition & Behavior 6(2), 231-252.

Schlager, D., & Risku, H. (2024). What does it take to be a good in-house translator? Constructs of expertise in the workplace. The Journal of Specialised Translation 42, 2-19.

Shreve, G. M. (2006). The deliberate practice: Translation and expertise. Journal of Translation Studies 9(1), 27-42.

Shreve, G. M., Angelone, E., & Lacruz, I. (2018). Are expertise and translation competence the same? Psychological reality and the theoretical status of competence. In I. Lacruz, & R. Jääskeläinen (Eds.), Innovation and expansion in translation process research (pp. 37-54). John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Tiselius, E. (2013). Same, same but different? Competence and expertise in translation and interpreting studies. Trial lecture for the doctoral degree. University of Bergen. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/265597567_Competence_and_Expertise_trial_lecture_for_the_doctoral_degree

Tiselius, E., & Hild, A. (2017). Expertise and competence in translation and interpreting. In J. W. Schwieter, & A. Ferreira (Eds.), The handbook of translation and cognition (pp. 425-444). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Wilss, W. (1976). Perspectives and limitations of a didactic framework for the teaching of translation. In R. W. Brislin (Ed.), Translation: Applications and research (pp. 117-137). Gardner Press.

Data availability statement

The dataset used for this study contains confidential information and is subject to non-disclosure agreements with the participants. Hence, the data are not publicly available.

1 ORCID 0000-0001-5372-2793, e-mail: hd@cc.au.dk↩︎

2 ORCID 0000-0003-3147-9715, e-mail: aol@cc.au.dk↩︎

3 ORCID 0000-0003-1677-2796, e-mail: kkz@cc.au.dk↩︎