Audio Describing Humour in Persian: The Case of Shaun the Sheep, Road Runner and The Pink Panther

Masoomeh Helal Birjandi1, University of Birjand

Hassan Emami2∗, University of Birjand

Saeed Ameri3∗∗, University of Birjand

ABSTRACT

Audio description (AD) has been a topic of high interest among translation studies researchers in the past two decades. Despite this, certain aspects of AD have been left unexplored, especially in non-European settings. One aspect of this accessibility service which has received little scholarly attention is humour. To fill this gap, this paper examines how Iranian audio describers navigate humour in the Persian AD of English silent animations. Three humour-driven silent animations with Persian AD were analysed, comparing the original and AD versions. The findings revealed that while some humorous elements remained undescribed, leading to a partial loss of comedic effect, audio describers effectively conveyed certain aspects of humour in most cases. In other words, the compound nature of humour helped retain its impact even when certain elements were omitted. Additionally, it appeared that the absence of dialogue in silent animations, coupled with their heavy reliance on visual elements, presented a notable challenge for audio describers in effectively conveying all the humorous elements.

KEYWORDS

Audio description, humour, silent animations, media accessibility, audiovisual translation.

1. Introduction

In today’s global landscape, notions of ‘human rights’, ‘equality’, ‘inclusion’ and ‘accessibility’ have become increasingly important. Numerous measures have been taken to create a more inclusive and fairer world. Article 27 of Universal Declaration of Human Rights aptly indicates that “Everyone has the right freely to participate in the cultural life of the community, to enjoy the arts and to share in scientific advancement and its benefits” (United Nations, 1948). Recognising the importance of providing access to audiovisual (AV) products for all individuals, media accessibility plays an important role in upholding human rights and social inclusion (Greco, 2022). Aiming to support blind or partially sighted individuals, audio description (AD) offers a verbal description or explanation of visual elements in films, TV shows, theatre performances and live events (Mazur, 2020; Perego, 2024). AD has recently become an independent area of research within audiovisual translation (AVT) and is now a recognised business sector with economic value and professional opportunities (Taylor & Perego, 2022).

To date, researchers have examined various aspects of AD that often pose challenges for audio describers, such as the description of characters, facial expressions and emotions (Benecke, 2014; Khoshsaligheh et al., 2022; Marra, 2023), alongside specific areas like providing ADs for children (López, 2010), describing cultural items (Jankowska, 2022; Maszerowska & Mangiron, 2014) and addressing taboos (Sanz-Moreno, 2018). These research advances notwithstanding, numerous issues are still waiting to be explored, including AD of humour. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, only a few studies have been conducted on the AD of humour in AV content (e.g., Dore, 2020; Martínez-Sierra, 2009, 2010, 2021).

The importance of translating humour lies in the fact that it is a fundamental human characteristic and an essential part of everyday communication and interaction (Kostopoulou & Misiou, 2024). In this context, translation in its various forms becomes vital since it serves as the medium through which humour is conveyed into a new culture. Following this, AD of humour becomes more crucial when addressing accessibility and human rights issues. Starr and Braun (2021) note that small actions and performance nuances play a role in the comedy, and explicitly describing them is crucial for sight-impaired audiences to fully grasp the humour in visually-driven scenes. AD, as Perego (2024) aptly maintains, “has sometimes been described as preventing blind people from feeling excluded” for example “when watching humorous audiovisual content on TV, wherein the visuals trigger laughter” (p. 17).

The limited body of research on the AD of humour (e.g., Dore, 2020; Martínez-Sierra, 2009, 2010, 2021) has primarily focused on the transfer of humour in specific comedic scenes from individual dialogue-driven films or series, with a particular emphasis on Italian and Spanish AD. The originality of this study, therefore, lies in its aims to examine the AD of humour in the specific context of Persian and to specifically investigate silent animations. This paper contributes to the limited existing literature and broadens our understanding of humour in Persian AD by qualitatively examining the transfer of humour in the Persian AD of three silent animations. The study aims to explore how Iranian audio describers deal with humour in the absence of spoken dialogues and verbal cues by shedding light on the challenges and strategies involved in conveying humour in AD. Examining silent animations can open up a new fascinating research area with significant potential for future studies in AD.

2. Literature review

2.1. Audio description of humour

The complexity of translating humour is undeniable, arising from the intricate interplay of linguistic features, metalinguistic elements, etc. (Kostopoulou & Misiou, 2024). When translating humour, the priority should be the comedic effect and strategy rather than a literal translation. The goal is to create a similar impact on the target audience, while maintaining a balance between cognitive impact and processing effort (Yus, 2016). Bucaria (2017) states that the focus of humour translation should be on effectively conveying its intent, typically to amuse the audience, in a way that feels natural and genuinely funny. Therefore, humour translation is a problem-solving process, requiring considerable effort and skill from the translator (Chiaro, 2017). When focusing on humour in AV texts, the challenge of translating meets an added layer of complexity. One reason behind this difficulty relates to the multimodal nature of AV texts, that are semiotic constructs. They derive meaning from the integrated use of different signs, encoded through acoustic and visual channels (Chaume, 2020). Therefore, the ultimate effect — in the case of humour, the humorous effect — is usually conveyed through both verbal and non-verbal channels simultaneously (Dore, 2020; Gambier, 2013). This implies that the information (humour here) the audiences receive relies on not only the words but also the sounds and images on screen.

Considering these complexities and the effect of the type of the AVT mode on humour reception (Dore, 2020), it appears that the AD of humorous texts has unique characteristics that influence how the describer treats humour. Indeed, the describer must compensate for the audience’s lack of access to the visual — and occasionally auditory — signifying codes that play a crucial role in creating the humorous effect (Martínez-Sierra, 2021). Following Bogucki (2019), visually expressed humour requires description. Starr and Braun (2021) argue that the challenge of describing humour arises from the need to convey multiple nuanced emotional states and detailed visual actions in a way that allows sight-impaired viewers to fully appreciate the humour. The lack of enough time to describe the humorous scene can diminish its impact on the audience (Maszerowska & Mangiron, 2014). Overall, when crafting descriptions for comedy films, audio describers should aim to preserve as many humorous elements as possible from the original content in the AD, ensuring that the intended comedic effect is not lost (Rubio, 2024).

The literature on the AD of humour is very limited in comparison to the conventional modalities of AVT, such as dubbing and subtitling, which have received significantly more attention in humour translation research (Antonini, 2005; De Rosa et al., 2014). Martínez-Sierra (2009) seems to be the first scholar who started the debate over the AD of humour. He employs relevance theory to see whether the intended cognitive effect can be properly derived from the AD version as the original version or not (Martínez-Sierra 2009). His analysis of some samples extracted from a mockumentary suggests that the absence of contextual assumptions in the AD version can negatively affect the cognitive effect, and consequently, the perception of humour. He highlights time constraints as a barrier to conveying necessary visual information in AD. In a later work that examines the AD of a British comedy film, Martínez-Sierra (2010) discovered that about two-fifths of the visually humorous instances were not described, possibly due to time restrictions. Therefore, the blind and visually impaired (BVI) audience missed out on their humorous impact.

Dore’s findings (2020) present a rather different perspective. In her book, she dedicates a chapter to the AD of humour and conducts a comparative analysis of English and Italian ADs of a comedy film. To this end, she employs Vercauteren’s guidelines (2007) and his four fundamental questions — what, when, how and how much should be described — about AD. The findings revealed notable differences between the two versions. Regarding “what,” Dore (2020) asserts that the English AD typically excel at conveying a character’s emotions through detailed depictions of actions and facial expressions, while the Italian AD lacks the necessary information in this regard. Answering “how much,” she notes that the word count in the English version is almost double that of the Italian version. She emphasises that while the number of words cannot necessarily be attributed to quality, it can be concluded from comparing the two ADs that the time restriction is not a justification for not mentioning the necessary details in the presented AD.

In his most recent work, Martínez-Sierra (2021) delves deeper into the transfer of humour from a fresh perspective. To explain the essence of humour, Martínez-Sierra refers to the Snell-Hornby’s (1988) concept of “prototype”, arguing that “we can understand jokes as continuums where there are no hermetic types, but prototypes (the elements) whose borders intermingle with other prototypical categories (other elements)” (p. 186). This statement elucidates why a compound joke can still be humorous for a BVI person even when no description is provided for some of its elements. By employing the taxonomy of humorous elements (Martínez-Sierra, 2006), in analysing an excerpt from a humorous TV show, he strengthens his argument and points out that while some humorous elements in this sample are not present in the AD version, this does not necessarily mean that the BVI audience fails to perceive any humour. Nevertheless, he highlights the necessity of conducting reception studies to determine the effect of humour on the AD audience accurately.

2.2. Audio description of silent films

It is expected that the AD of silent films differs significantly from that of dialogue-based films. In dialogue-based films, dialogue typically serves as the primary accessible conduit to the blind audience, providing essential context and information and driving the plot (Vercauteren & Reviers, 2022). Indeed, the absence of this element in silent films makes the task of the audio describer more challenging. The audio describer of the silent film The Artist (2011) reflects on this matter, explaining that AD in most films “will weave its way in between dialogue, signposting the salient point of the movie” (para.8). He adds that in such a case, “it was more of a ninety-minute narration, which relied totally on the audio description to tell the story and convey the characters’ highs and lows” (Stevens & Clare, 2014, para.8). To put it differently, since the audience of silent films receives no background sounds or dialogue that may enhance their understanding of the story, the audio describer is supposed to describe every detail in an explicit way (SPECIAL VIEW, 2021). Therefore, audio describers face a huge number of images and visual-based sounds, from which they should distinguish the most important ones that need to be described in such a way that the audience can be provided with a clear and coherent understanding of the film’s narrative.

Both in Iran and elsewhere, it seems that the AD of silent animations has garnered less attention compared to films with dialogues, which can be attributed to the challenges that arise from describing silent films. This paper, as one of the first studies that included silent animations as its corpus, aims to fill this gap by examining the transfer of humour in the Persian AD of three silent comedy animations.

3. Research methods

By adopting a qualitative and exploratory approach, the present study investigates the transfer of humour in Persian ADs. This research is informed by descriptive multimodal analysis, as multiple signifying codes in the semiotic configuration of AV texts operate simultaneously to create meaning (Chaume, 2012). As Martínez-Sierra (2021) mentions, certain codes (like sound elements) are naturally accessible, while others (like visual gags) require description for blind audiences. Consequently, blind audiences may miss visual cues unless they are properly described.

A corpus of three comedy silent animations was selected based on two specific criteria: they have not been previously examined in related studies, and have been provided with AD by two most well-known Iranian NGOs, Sevina4, and Mahale Nabinayan5. It is important to note that Sevina also provides ADs for Iran’s leading streaming service, Filimo, while Mahale Nabinayan, a non-profit community, offers Persian ADs on its website. The silent animations featured in this paper included episodes from the series Shaun the Sheep (2007-2020), Road Runner (1994) and The Pink Panther (1969-1980).

After watching each episode, the three researchers collaboratively identified two humorous scenes in which the humour appeared to be more visually based and tangible than in others, ensuring an objective selection process. Subsequently, for a more accurate and objective examination, the potential humorous elements were examined and extracted based on a taxonomy of eight humorous elements in AV texts offered by Martínez-Sierra (2021). He elaborates on these elements:

Referential elements: Some humour is based on culture-specific references

Preferential elements: Some humour is based on features or topics popular in certain cultures. This popularity arises from general cultural preferences rather than unique cultural traits

Linguistic elements: Humour comes from linguistic features, such as wordplay, puns or funny dialogue

Paralinguistic elements: Humour comes from how something is said (tone, silence, pauses)

Visual elements: Humour comes from what we see on screen (funny faces).

Graphic elements: Humour comes from a written text in the scene

Acoustic elements: Humour comes from sound or music (funny noises)

Non-marked humorous elements: Humour that does not fit into the above categories but still makes viewers laugh

After comparing the identified elements in the original version and their counterparts in the AD version, the audio describers’ alternatives in dealing with them were examined. Like any research on humour translation, which is inherently subjective, a degree of subjectivity may influence the decision to include or exclude elements deemed humorous (Dore, 2020). To mitigate this impact of subjectivity, the selection of humorous scenes and the process of analysing the scenes and their ADs were carried out by a team of three researchers with backgrounds in AVT and AD. This collaborative approach proved particularly valuable in instances where differences of opinion emerged, necessitating discussion to effectively resolve discrepancies. To further enhance the objectivity of the data analysis, an additional researcher with a strong background in AD was invited to independently review the analysis. Despite these efforts, arriving at a completely objective analysis remains elusive.

4. Results

The analysis of six humorous scenes is presented below. To aid reader comprehension, each sample is accompanied by a contextualising table. The tables consist of a contextualisation of the original (undescribed) version, and the corresponding AD (in back translation from Persian) for each segment as well, which allows for a comparison between the original version and the AD version. Additionally, the tables include time slots indicating each sample’s start and end points in the original version. Following each table, a detailed discussion of the humorous scene and its adaptation in AD is provided, focusing on signifying codes and humorous elements.6

4.1. Case one: Party Animals episode from Shaun the Sheep7

| Sample 1 | |

| TCR: 00:00:52 - 00:01:06 | |

| Original Version | AD Version |

| Outside the house, Bitzer and other sheep are playing cards. Bitzer shuffles the cards skilfully. | Back translation (BT): Over there in the yard, the guard dog and the sheep are playing cards with each other. The guard dog heartily shuffles the cards. |

| The sheep are bored as one of them yawns and the other one baas in a complaining tone. | BT: The sheep are watching too and saying, hurry up, shuffle the cards! |

| With closed eyes, Bitzer throws the cards to the sheep. Then, he opens his eyes and sees the cards stuck in sheep’s wool. | BT: The guard dog throws the cards and throws them toward the door and wall [The audio describer laughs here]. |

Table 1. Sample 1 from Party Animals.

Analysis: As seen in the left image in Figure 1, the first humorous instance that can be observed in this scene relates to Bitzer skilfully shuffling the cards, with a pose — as if he is a skilled croupier — that adds to the humour. This visual element is considered to be humorous or at least contributes to the overall comedic effect in conjunction with other elements. The subsequent elements that are assumed to elicit laughter from the audience are respectively a visual element (the image of sheep looking at Bitzer with the expression of boredom), an acoustic element (baa sound) and a paralinguistic element (complaining tone of baa sound). The final humorous visual element occurs when Bitzer shuffles the cards with his eyes closed as if he is very professional and has done it countless times. He then opens his eyes to discover that the cards are stuck in the sheep’s wool and on their faces, as shown in the right image in Figure 1. This is further emphasised by visual and mobility signifying cues, as the sheep appear frustrated, conveying this through eyes and shaking heads, as if expressing their disappointment, representing itself as a non-marked element (Table 1).

Figure 1. Sample 1 images from Party Animals.

In the AD version, as seen in Table 1, the description mentions Bitzer shuffling the cards, but the comedic effect is not effectively conveyed. Specifically, humour is not fully conveyed in the AD, meaning Bitzer’s pose as a skilled croupier is not explicitly mentioned. This likely occurs because the describer did not perceive the event as humorous or did not consider it worth describing. Visual elements like the sheep waiting, the baa sound (acoustic element), and its querulous tone (paralinguistic element) are briefly represented in the AD. There is a short silence for the audience to hear the baa, followed by the describer’s remark, “Hurry up, shuffle the cards!” to effectively convey the humorous element. Here, the description prioritises these elements due to time constraints. Finally, the last element is accompanied by the describer’s laugh, likely to ensure the humour is conveyed to the audience, adding an emotive touch to the AD.

The humour of the final visual element, where the cards stick in the sheep’s wool, is present but lacks specific details. Instead of noting that the cards are caught in the wool, the description only suggests that the cards are thrown around. This results in a sense of humour, but the lack of accurate description may affect the audience’s full understanding of the comedic effect. We believe this is due to the fast-paced nature of the events on screen, which leaves little room for the describer to include details, focusing only on the essential elements. This observation could serve as a hypothesis for future research, particularly based on feedback from BVI viewers.

| Sample 2 | |

| TCR: 00:04:18 - 00:05:25 | |

| Original Version | AD Version |

The Farmer and the flock are dancing. With a food tray in his hands, the farmer comes. He is awestruck as his eyes fall on Shirley. |

BT: Wow, what a party it is with the presence of sheep, each of them wearing a special dress. A masquerade party where everyone is a sheep but each of them wears different clothes and Mr. Farmer thinks they are real guests. They wear weird animal clothes. Mr. Farmer is also giving service to the guests. His eyes fall on a sheep sitting on the other side of the sofa. It catches his eyes so badly, telling himself let’s talk to her and win her heart. |

Shirley is sitting in an attractive pose on the couch, with red high heels and crossing legs. Immediately, the Farmer uses a mouth spray. |

_ |

| He sits beside Shirley on the couch and offers her food. Shirley smells it and, in a second, swallows the whole food. | BT: He offers her a cake. That sheep suddenly smells the cake and swallows it in one gulp. |

| The Farmer gets surprised by the Shirley’s action. | BT: Wow! Mr. Farmer gets surprised saying bravo! What a mouth she has! [The audio describer modifies his tone and voice when speaking on behalf of the farmer] |

| The Farmer yawns and puts his hand around Shirley’s shoulder. | BT: In short, Mr. Farmer just yawns and has become friends with that sheep. |

| What the Farmer does surprises Shirley. With beseeching eyes, he looks at Shaun and Britz. | _ |

Shaun and Britz cover the Farmer’s eyes to manage the situation and take him out of the house. The Farmer is surprised as they uncover his eyes. A red car is there. Happily, they go back inside the house. As they leave the place, the car, which is, in fact, a cardboard cutout, falls. |

BT: Others find the situation so awkward. They cover Mr. Farmer’s eyes and take him to the door to give him the gift. Well, Mr. Farmer is also very happy. What can be his gift? They remove the blindfold from his face saying “ta-da”. Wow, a very beautiful car. Mr. Farmer gets so happy. He thanks them and everyone goes back home again. Hey guys, it wasn’t a car. It was a replica. The replica was big, and Mr. Farmer thought it was a real car. [The audio describer makes hesitations and pauses when stating these sentences] |

Table 2. Sample 2 from Party Animals.

Analysis: As shown in Table 2, the guests—who are actually sheep in costumes, as seen in the left image of Figure 2—and the farmer are dancing and having fun together. This scene’s primary source of humour stems from the farmer’s infatuation with one of the sheep and the alternative suggested by the other sheep to prevent a disaster. Several elements collaborate to convey the intended effect. The farmer’s facial expression (his wondering face when seeing one of the female guests) is the first humorous visual element which is a hinting at his crush on the guest, a non-marked element. Another potentially humorous element, a non-marked element, highlights the farmer’s lack of intelligence in recognising that the guest is Shirley, one of his own sheep and not a woman in a sheep costume. While these elements seem to be present in the AD version, the audio describer diverges from typical practice. Instead of describing the actions, he interprets what he sees and even provides dialogue for the characters, who are actually silent in the original version. This approach is uncommon in AD practice and deviates from the established guidelines that advocate objectivity (Colmenero, 2024).

Figure 2. Sample 2 images from Party Animals.

As to the humorous elements of the next part, there can be seen two more potentially humorous visual elements, the humorous Shirley’s pose and the farmer using breath freshener when he intends to approach her. The latter is also accompanied by an acoustic element which is the spraying sound effect. The two visual elements remain undescribed in the AD version, which prevents the audience from experiencing their effect. The acoustic element related to the spraying act, however, is present in the AD version but there is no reference to its visual aspect. The number of visual elements keeps increasing when the farmer offers the food to Shirley, and she smells it and unexpectedly swallows it. Here, humorous visual elements include the farmer’s actions while sitting next to her and Shirley’s bewildered expression, which conveys a silent plea for help. These elements are not completely described in the AD version (Table 2).

The scene ends with the sheep’s action to handle the awkward situation. The humorous effect intensifies when the farmer’s birthday gift collapses (the middle image in Figure 2), revealing that it is just a cardboard cutout shaped like a car, not an actual vehicle. The farmer’s joyful reaction to seeing the car serves as a visual element, while his foolishness in failing to recognise it as a fake is a non-marked element. The mentioned elements seem to be present in the AD, albeit in a subjective manner. As Table 2 shows, the audio describer reveals the humour in the final part based on their own interpretation, rather than allowing the audience to discover it independently. Using words and expressions like “ta-da” and “wow” by the audio describer also adds to this subjectivity. All in all, the scene can still be humorous for the BVI audience, although some elements are lost.

It is worth noting that the audio describer’s delivery includes hesitations when stating some of the sentences. This can be potentially due to reasons such as the complexity of the scene, time constraints and the challenge of synchronisation. Although the AD provider claims to use pre-written AD scripts, the presence of hesitations and pauses in some parts of the AD suggests a deviation from the script, indicating improvisation during recording. This issue can negatively impact the audience’s experience by reducing their comprehension and creating confusion.

4.2. Case two: Chariots of Fur episode from Road Runner8

| Sample 1 | |

| TCR: 00:00:43 - 00:01:07 | |

| Original Version | AD Version |

| Coyote is chasing after Road Runner. He has a knife and fork, and his tongue is out. | BT: Road Runner is running fast on the road in the middle of the street and dust rises up behind him. As he is running, he looks behind. Coyote is also running. He has a knife in his right hand and a fork in his left hand. His mouth is open, and his tongue is out of happiness. |

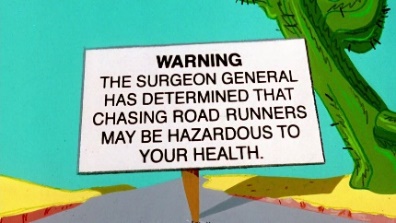

While chasing, he sees a sign on the road: WARNING. THE SURGEON GENERAL HAS DETERMINED THAT CHASING ROAD RUNNERS MAY BE HAZARDOUS TO YOUR HEALTH. He slows down and stops in front of the sign to read it. |

BT: After running, Coyote closes his mouth and looks ahead. In the middle of the road, there is a sign that says: Warning, following Road Runners can be harmful to your health. |

| Coyote bends down and reads the sign for seconds. Considering it cheesy, he points to the sign and starts laughing. | BT: Coyote looks at the board mockingly. |

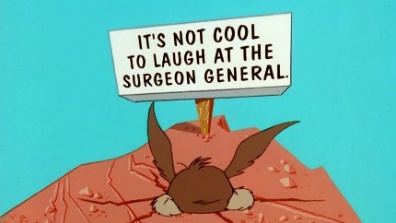

Suddenly, Road Runner comes speeding and beeps behind Coyote. Due to speed, Road Runner hits Coyote and throws him into the air. Coyote hits an overhanging outcropping, and his head gets stuck in it. With his head smashed against the outcropping, Coyote sees another sign at the far end that reads: IT’S NOT COOL TO LAUGH AT THE SURGEON GENERAL. |

BT: Suddenly Road Runner appears from behind him. Coyote jumps into the air in fear. His head gets stuck in a boulder and a sign appears in front of him that reads: It is not good to laugh at the advice of the surgeon general. |

Table 3. Sample 1 from Chariots of Fur.

Analysis: The scene starts with Coyote chasing after Road Runner. Here, the appearance of Coyote, holding a knife and fork in his hands and his tongue sticking out as he chases after Road Runner in hopes of trapping it, can be considered a visual element that contributes to the humour. This part is completely present in the AD. The following potentially humorous element is a graphic element, a sign displaying “WARNING. THE SURGEON GENERAL HAS DETERMINED THAT CHASING ROAD RUNNERS MAY BE HAZARDOUS TO YOUR HEALTH” (the left image in Figure 3). This element is accompanied by a humorous, non-marked element: the absurdity of the Surgeon General’s warning about the health risks of chasing Road Runners. Indeed, this graphic element references health warnings on cigarette packages: a referential element. The linguistic manipulation of the original phrase “Warning: The Surgeon General Has Determined That Cigarette Smoking Is Dangerous to Your Health” creates a humorous linguistic element that adds an extra layer of humour. The humorous impact of this element is partially lost in AD since the describer omits the translation of the phrase “surgeon general”. While the description still makes sense, it relies on the BVI audience to make the connection between the warning on a cigarette box and the warning in this scene.

Figure 3. Sample 1 images from Chariots of Fur.

The subsequent humorous visual element is created when Coyote scoffs at the sign, indicated by his laughing sound which is a paralinguistic element, as seen in the second image in Figure 3. A non-marked humorous element arises as the audience anticipates a disaster befalling Coyote due to his scoffing. The overall humorous effect of this part is somehow conveyed; however, the laughing sound — a paralinguistic element — that exists in the original version cannot be heard in the AD version.

Another visual element occurs when Road Runner hits Coyote, causing him to jump into the air. This humorous image is accompanied by an acoustic element — a beep sound by Road Runner. These visual and acoustic elements, along with another visual element of Coyote’s head getting stuck in the outcropping, are totally present in the AD version and can create a humorous effect. Nonetheless, the AD does not include the onomatopoeic word “beep”, a graphic element above Road Runner’s head. Only the sound is heard in the AD, with no indication that “beep” appears above Road Runner’s head. This written word may contribute to the overall comedic effect of the scene. The last part of this scene includes another graphic element: “IT’S NOT COOL TO LAUGH AT THE SURGEON GENERAL” (the right image in Figure 3). This is accompanied by a non-marked element, which represents the consequence of Coyote’s scoffing at the surgeon’s general warning. As previously mentioned, the phrase “Surgeon General” is not translated in the first element. Figure 3 illustrates how these two graphic elements are interrelated in meaning. As a result, the BVI audience may struggle to grasp the full humorous effect of this part and, consequently, of the entire related scene.

| Sample 2 | |

| TCR: 00:01:08 - 00:01:38 | |

| Original Version | AD Version |

To catch Road Runner, Coyote hides behind a cliff, leaves some seeds on the road, and puts two signs on the seeds that say: “FREE” and “BIRD SEED.” He stays hidden behind the cliff and waits for Road runner to arrive. |

BT: Coyote drops some bird food on the road and also installs a sign that the bird food is free. He hides behind a stone. |

| Road Runner arrives, looks at the sign, and starts eating the seeds. | BT: Mig Mig also arrives and immediately starts eating the seeds. |

While eating, Coyote sneaks up behind him and, with a knife and fork in his hands, tucking a napkin into his neck and licking his lips, gets ready to eat him. Road Runner senses the danger, extends his neck around, and beeps behind Coyote. |

BT: Coyote comes out from behind a boulder. Quietly, stands behind Road Runner’s head and wants to attack but suddenly Road Runner appears from behind with his long neck, while Road Runner’s tail is still in front. |

| Coyote gets spooked and jumps into the air. | Coyote jumps into the air in fear. |

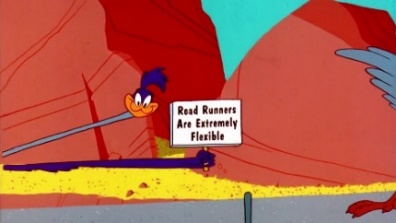

| With his extended neck, Road Runner stares at the camera and displays a sign: “Road Runners Are Extremely Flexible”. | BT: Mig Mig also shows a sign on which it is written that Road Runner is very flexible. |

| Road Runner goes back to the bird seeds place and leaves the scene while Coyote falls and bumps into the road, taking the shape of an accordion. | _ |

Table 4. Sample 2 from Chariots of Fur.

Analysis: In this scene, Coyote attempts to trick Road Runner by leaving some seeds on the road and labelling them with signs that read “FREE” and “BIRD SEED”. The visual element related to Coyote’s hiding has the potential to be humorous but is not described in the AD version, resulting in its loss. Another visual element appears as Road Runner extends his neck around Coyote, accompanied by an acoustic cue — a sudden “beep” that startles Coyote and makes him leap into the air, creating yet another visual gag, as shown in the left image in Figure 4. The action of Road Runner extending his neck and Coyote’s startled reaction contribute to a non-marked element of subverting Coyote’s plan and highlighting his repeated failures in catching Road Runner. These elements are present in the AD version, as indicated in Table 4. Another humorous graphic element is a sign that reads “Road Runners Are Extremely Flexible”, which Road Runner reveals after extending his neck and startling Coyote (the second image in Figure 4). This element serves as a humorous display of the Road Runner’s flexibility. Thanks to the AD, this graphic element is properly translated into Persian and thus accessible to the audience.

Figure 4. Sample 2 images from Chariots of Fur.

The last visual element occurs when Coyote, previously startled into the air, falls back onto the road, and takes on the shape of an accordion, as seen in the right image in Figure 4. The sound of the accordion, which is present in the original version, serves as an acoustic element that adds to the humour of this scene. This scene is left undescribed in the AD, diminishing its comedic impact. Although this acoustic sound can be heard in the AD, the lack of explicit reference renders it ineffective for the BVI audience. While most of the elements of this scene are present in the AD, the absence of a few elements means that the BVI audience may not fully experience the intended humour.

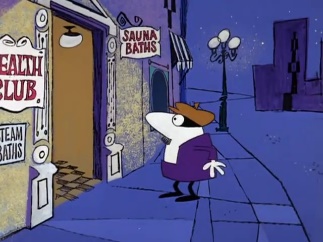

4.3. Case three: Lucky Pink episode from The Pink Panther9

| Sample 1 | |

|---|---|

| TCR: 00:01:11 - 00:01:34 | |

| Original Version | AD Version |

| Happily, the robber returns to the bank. The Pink Panther starts following the robber to return the horseshoe. | BT: The robber goes to the bank again to empty it. The Pink Panther sees the robber running away. He runs fast to give him the horseshoe and says this horseshoe is yours. |

He abruptly stops as he sees the robber. The robber places his gun against the woman’s back. As the woman decides to surrender her bag, the Pink Panther slips the horseshoe into the robber’s pocket. The woman starts running after the robber, hitting him with her bag. |

BT: At the same time, the robber sees a woman and wants to steal her bag. As soon as he wants to steal the bag, the Pink Panther puts the horseshoe in his pocket and that causes the lady to attack him and not be able to steal from him. |

| The robber retrieves the horseshoe in his pocket and throws it away. | BT: When the robber sees that the horseshoe is in his pocket, he throws it out. |

| The Pink Panther finds the horseshoe in front of him. Thinking that the robber has lost it, he starts following him to return it to him. | BT: The Pink Panther thinks that it has fallen out of the robber’s pocket and therefore runs after her. |

Table 5. Sample 1 from Lucky Pink.

Analysis: The scene starts with a visual element: the Pink Panther, trying to return the horseshoe to its owner, quietly puts it in the robber’s pocket (Table 5). This visual element is followed by a non-marked element as well, portraying the Pink Panther’s naivety as he remains unaware of the horseshoe’s ominous nature and believes he is helping.

Figure 5. Sample 1 images from Lucky Pink.

As seen in the left and middle images in Figure 5, the woman’s demeanour shifts immediately after the Pink Panther places the horseshoe in the robber’s pocket. Due to the bad luck the horseshoe brings to the thief, she then begins hitting him with her bag. This part can also constitute a humorous visual element which is once again accessible to the BVI audience in the AD. Pink Panther’s second attempt to take the horseshoe and return it to its owner, reinforces the humorous visual element and its following non-marked element of the Pink Panther’s naivety (the right image in Figure 5). This element seems to be the foundation for humour and is repeated throughout the film. The AD version accurately reflects the three visuals shown in Figure 5 along with other associated elements, helping the BVI audience get the humorous effect.

| Sample 2 | |

|---|---|

| TCR: 00:02:42 - 00:03:16 | |

| Original Version | AD Version |

| Cautiously and quietly, the robber tiptoes toward a place. | BT: In the next scene, the robber moves stealthily again. He wants to go somewhere. |

| As the robber is tiptoeing, the Pink Panther notices him through a door. | BT: The Pink Panther sees him. |

| The robber enters a building where the words “SAUNA BATH” are written on the wall beside the entrance. | BT: The robber enters a building. |

| The Pink Panther enters the sauna bath right after him with the horseshoe in his hand. | BT: The Pink Panther follows him to get the horseshoe to him. |

The Pink Panther opens a door on which is written: STEAM ROOM He enters the room. Inside the room, there is a massive amount of steam. Nothing can be seen but only the robbers and the Pink Panther’s eyes. The Pink Panther gets closer to the robber and puts the horseshoe there. The pink panther leaves the room. |

BT: The robber goes into a bathroom to take a shower. The Pink Panther also enters the bathroom and, in that steam, and hot water, gives the horseshoe to the robber and comes out. |

Immediately, the robber, with a towel wrapped around his body, exits the room. A group of police officers comes out of the steam room with guns firing and towels over their bodies following the robber. |

BT: As soon as he gives the horseshoe to the robber, the policemen start chasing the robber. All of them are in bathing suits. |

| The Pink Panther is standing near the doorstep, watching what is happening. As the robber throws the horseshoe away, he picks it up as he did before. | BT: While running away, the robber throws the horseshoe to the other side again. |

Table 6. Sample 2 from Lucky Pink.

Analysis: In this scene (Table 6), the robber tiptoes and cautiously approaches his destination. He enters a building with a written sign on the wall that reads “SAUNA BATH”, as shown in the left image in Figure 6. This is a significant graphic element, as it surprises the audience by raising the question of why a robber would go to such a place, creating a non-marked humorous element. Another graphic element appears when the Pink Panther follows the robber and enters a room with a door labelled “STEAM ROOM”. The describer does not mention the first graphic element (the place the robber is going), potentially causing the audience to miss the humour derived from the absurdity of a robber going to a sauna while in the middle of a robbery. However, in describing the following parts, the audio describer refers to the second graphic element when mentioning that the Pink Panther follows the robber into the steam room. The scene where the Pink Panther follows the robber into a steam room is another visually driven, potentially humorous moment. This element is also present in the AD version.

Figure 6. Sample 2 images from Lucky Pink.

Another visual element emerges when the Pink Panther enters the room filled with a massive amount of steam, obscuring most of the scene except for the eyes of the robber and the Pink Panther (the middle image in Figure 6). He puts the horseshoe there and leaves the place. This image creates a rather humorous visual instance. Considering the AD version, the audio describer does not mention the details at all. Indeed, the BVI audience is not presented with a description of the scene where only two pairs of eyes blinking can be seen. The issue lies in the lack of sufficiently detailed descriptions of the visual elements, a shortcoming also noted in Dore’s (2020) study. The last visual element occurs when the robber, with the officers running after him, leaves the steam room, all wrapped in a towel (the right image in Figure 6). The visuals clearly show that they are shooting with one hand while holding their towels with the other. This detail is simply missed, and its intended effect is not conveyed by only mentioning bathing suits. Therefore, the general humorous effect seems to be partially conveyed through AD. It is worth mentioning that the audio describer seems to employ a cheerful and amusing tone in the description of the humorous scenes, which may compensate for the loss of the effect. This subjective approach may help BVI viewers experience an immersive and engaging viewing (Fryer, 2016).

5. Discussion and conclusion

This paper examined how the Iranian audio describers handle the humour in AD of foreign silent animations. Results suggest that, in most cases, the audio describers conveyed the humorous elements and the resulting humorous effect, although not completely. This finding aligns with what Martínez-Sierra (2021) mentions regarding the compound nature of a joke. He is of the view that a joke within an AV text comprises various elements that collectively create the humorous effect — not just individually but through their convergence. Accordingly, a joke may resonate humorously with BVI audience even when AD has not been provided for some elements, as they can still access other contributing elements (2021). However, as Martínez-Sierra (2021) aptly states, reception studies would be crucial for assessing the actual impact of these alterations.

It is known that comedy films or sitcoms use language, sounds and images as the three primary vehicles for conveying humour, working together to create the ultimate comedic effect (Zabalbeascoa & Attardo, 2024). In silent animations, the responsibility of conveying meaning and humour primarily lies with the two remaining carriers, images and background sounds, as there is no dialogue to provide additional context. In dialogue-based films, the audio describer typically inserts descriptions during pauses between lines of dialogue. However, silent films need continuous narration through AD to convey the story and characters’ emotions (Stevens & Clare, 2014). As our analysis showed, silent animations rely heavily on visual storytelling, rapid scene changes and sound effects, leaving limited space for detailed narration. Consequently, the describer is forced to focus only on the most essential elements. Due to time constraints, describers typically create more concise descriptions, which may result in the omission of certain details (Martínez-Sierra, 2009, 2010). Although this limitation cannot be the only factor leading to imprecise descriptions in certain cases (Dore, 2020), it may result in an AD that lacks sufficient humorous elements.

When an Iranian audio describer describes an English silent animation that may contain some visual verbal elements in English, they face a unique challenge. In these cases, audio describers should navigate two types of transfer: converting visual elements into words and translating foreign words into Persian. When dealing with the humour embedded in these elements, the describer, or translator, must ensure that the humorous essence is preserved in the translation. It is important to note that while most guidelines and researchers emphasise the AD of on-screen texts (Braun & Orero, 2010; Matamala, 2014; Vercauteren, 2007), not all texts could be easily described. For instance, in Road Runner, certain graphic elements, such as “beep” appear in the form of onomatopoeic words in the air. Although the sound of beep can be heard in the AD, it is very challenging to describe that the word also appears in the air at the same time. The inevitable loss of onomatopoeic words like “SNAP,” “TWANG” and “SLUMP” in the AD of the animation may negatively impact the intended humorous effect. This is an important issue that should be examined through reception studies.

Regarding the AD of crucial sounds, some researchers have emphasised their inclusion in ADs (Szarkowska & Orero, 2014; Vercauteren & Reviers, 2022). However, this importance is amplified in silent animations, as they lack additional sound cues like dialogues. The analysis indicated that in these animations, due to the substantial volume of images requiring AD, the synchronisation of sounds and related images is often lost in the AD, resulting in a potential loss of humorous effect of the related sounds. Furthermore, there were cases where the visual element contributing to the acoustic element was left undescribed, thus, while the acoustic element was present in the AD, there was no visual element to complete its humorous effect. To illustrate this, there was no AD for the coyote in the Road Runner case morphing into an accordion after a fall (see case two). Consequently, despite the presence of the accordion sound in the AD, its intended humour likely went unnoticed as there was no description of the scene. These cases show that the Persian AD tradition, still in its infancy, has not yet developed norms and conventions for implementation in practice. As a result, the practice has become haphazard and based on personal value judgments.

In addition, an additional aspect emerging from the analysis indicated that elements like timing or sequence of visual events may contribute to creating a humorous effect. For instance, the seamless coordination of music and sounds with the characters’ physical movements (known as Mickey Mousing technique) in the case of Road Runner created an additional layer of comedic timing and harmony. Conveying the humorous effect through description alone can be fairly challenging for the describer. Arguably, this calls for accessible filmmaking—where filmmakers consider how their work will be received by BVI audiences, integrating accessibility from the inception of the AV product (Romero Fresco, 2019).

When considering the role of humour in AD, it is crucial to recognise the impact of the audio describers’ language, rhythm, tone and intonation in creating meaning (Caro, 2016; Holsanova, 2022). It was found that the audio describers sometimes used interjections, like laughter, and adjusted their tone and voice to match the events in the film. Indeed, compensation occurs when audio describers, feeling unable to fully convey the humour due to limitations, make up for it using a paralinguistic element like their laughter.

Facial expressions could also generate humour in some contexts. In silent animations, AD is essential for conveying these expressions to achieve the intended humorous effect. The analysis revealed that the audio describers primarily used the explicitation strategy (Mazur, 2014) to convey potentially humorous facial expressions. Interestingly, in some cases, the describer employed a new strategy by speaking on behalf of the characters, and using tonal shifts to convey the emotions reflected on the characters’ faces. Indeed, the describer apparently adopted a dynamically-oriented AD for such reasons as preserving the narrative flow while ensuring clarity for the viewers (see Mazur, 2014). The use of this approach is largely due to the fact that the primary audiences for these animations are young people and children. Concerning the importance of aligning the style of the film with its audience (Vercauteren, 2007), the employment of this technique could be attributed to the audio describer’s endeavour to resonate with the film’s style and, in turn, with the audience. It is worth noting that the audio describer of Party Animals and Lucky Pink is a well-known Iranian voice actor—renowned for dubbing animated characters—who appears to have applied his dubbing skills to the AD.

On the whole, it appears that in silent animations, contrary to the emphasis placed by most AD guidelines on maintaining objectivity (Colmenero, 2024), the describers exhibited a higher degree of subjectivity, and at times created an emotive AD version. The shift toward subjectivity makes sense due to the unique nature of silent animations. Indeed, the absence of dialogue may prompt the describer to construct and convey the narration based on their own interpretation. According to Braun and Starr (2021), “a degree of subjectivity in the interpretation process is inevitable in AD” (p. 3). Nonetheless, these interpretive and subjective descriptions should not be haphazard; instead, they should be guided by the describer’s strong justifications and any training they have received that instructs them on how to act methodically (see Soler Gallego, 2019).

It is also crucial to note that no official guidelines for AD have been established in Iran so far. Consequently, the Iranian audio describers currently lack a standardised framework to follow. This lack of regulations may result in a wide range of individual approaches and also a high degree of subjectivity in AD, as observed in the examined cases. As noted by Khoshsaligheh and Shafiei (2021), Iranian AD providers rarely receive training and may lack the necessary competencies to produce well-executed ADs. Given the importance of high-quality and consistent ADs, there appears to be a pressing need for the development of standardised Persian AD guidelines.

On a final note, there remain several aspects that warrant further investigation. The limited scope of this study highlights the need for further research with diverse samples of AD to enhance our understanding of how humour is conveyed. This paper does not claim the generalisability of the findings; they should be considered exploratory, presenting questions for further investigation. Additionally, in-depth interviews with audio describers provide insights into the choices they make or the challenges they face in describing humour. Given the subjective nature of humour analysis, reception studies on BVI individuals’ views could complement the analyses. The complexities attributed to the AD of silent animations may suggest a need for the establishment of specific guidelines tailored to them. Therefore, future studies should focus on best practice recommendations for addressing the challenges of humour in AD, including how much the audio describer can apply their subjective and interpretive descriptions.

References

Antonini, R. (2005). The perception of subtitled humor in Italy. HUMOR: International Journal of Humour Research, 18(2), 209-225. https://doi.org/10.1515/humr.2005.18.2.209

Benecke, B. (2014). Character fixation and character description. In A. Maszerowska, A. Matamala, & P. Orero (Eds.), Audio Description: New perspectives illustrated (pp. 142–157). John Benjamins.

Bogucki, Ł. (2019). Areas and methods of audiovisual translation research (3nd ed.). Peter Lang.

Braun, S., & Orero, P. (2010). Audio description with audio subtitling – an emergent modality of audiovisual localization. Perspectives, 18(3), 173–188. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2010.485687

Braun, S., & Starr, K. (2021). Introduction: Mapping new horizons in audio description research. In S. Braun & K. Starr (Eds.), Innovation in audio description research (pp. 1-12). Routledge.

Bucaria, C. (2017). Audiovisual translation of humor. In S. Attardo (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of language and humor (pp. 430-443). Routledge.

Caro, M. R. (2016). Testing audio narration: the emotional impact of language in audio description. Perspectives, 24(4), 606–634. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2015.1120760

Chaume, F. (2012). Audiovisual translation: Dubbing. St. Jerome.

Chaume, F. (2020). Dubbing. In Ł. Bogucki & M. Deckert (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of audiovisual translation and media accessibility (pp. 103-132). Palgrave Macmillan.

Chiaro, D. (2017). Humor and translation. In S. Attardo (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of language and humor (pp. 414-429). Routledge.

Colmenero, M. O. L. (2024). Subjectivity and creativity versus audio description guidelines. In A. Marcus-Quinn, K. Krejtz, & C. Duarte (Eds.), Transforming media accessibility in Europe (pp. 39–52). Springer Nature.

De Rosa, G. L., Bianchi, F., De Laurentiis, A., & Perego, E. (Eds.). (2014). Translating humour in audiovisual texts. Peter Lang.

Dore, M. (2020). Humour in audiovisual translation theories and applications. Routledge.

Fryer, L. (2016). An introduction to audio description: A practical guide. Routledge.

Gambier, Y. (2013). The position of audiovisual translation studies. In C. Millán & F. Bartrina (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of translation studies (pp. 45-59). Routledge.

Greco, G. M. (2022). The question of accessibility. In C. Taylor & E. Perego (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of audio description (pp. 13-26). Routledge.

Holsanova, J. (2022). A cognitive approach to audio description: production and reception processes. In C. Taylor & E. Perego (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of audio description (pp. 57-77). Routledge.

Jankowska, A. (2022). Audio description and culture-specific elements. In C. Taylor & E. Perego (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of audio description (pp. 107-126). Routledge.

Khoshsaligheh, M., & Shafiei, S. (2021). Audio description in Iran: The status quo. Language and Translation Studies, 54(2), 1-30. https://doi.org/10.22067/lts.v54i2.2101-1006(R2)

Khoshsaligheh, M., Shokoohmand, F., & Delnavaz, F. (2022). Persian audio description quality of feature films in Iran: The case of Sevina. International Journal of Society, Culture & Language, 10(3), 58-72. https://doi.org/10.22034/ijscl.2022.552176.2618

Kostopoulou, L., & Misiou, V. (2024). Introduction: The transmedial turn in humour translation. In L. Kostopoulou & V. Misiou (Eds.), Transmedial perspectives on humour and translation (pp. 1-12). Routledge.

López, A. P. (2010). The benefits of audio description for blind children. In J. Díaz Cintas, A. Matamala, & J. Neves (Eds.), New insights into audiovisual translation and media accessibility (pp. 213-225). Brill.

Marra, L. (2023). The expression of emotions in the Spanish and Italian filmic audio descriptions of the King’s Speech. Journal of Audiovisual Translation, 6(2), 33–54.

Martínez-Sierra, J. J. (2006). Translating audiovisual humour. A case study. Perspectives, 13(4), 289-296. https://doi.org/10.1080/09076760608668999

Martínez-Sierra, J. J. (2009). The relevance of humour in audio description. inTRAlinea, 11. www.intralinea.org/archive/article/1653

Martínez-Sierra, J. J. (2010). Approaching the audio description of humour. Entreculturas, 2, 87-103.

Martínez-Sierra, J. J. (2021). Audio describing humour: Seeking laughter when images do not suffice. In M. Dore (Ed.), Humour translation in the age of multimedia (pp. 177-195). Routledge.

Maszerowska, A., & Mangiron, C. (2014). Strategies for dealing with cultural references in audio description. In A. Maszerowska, A. Matamala, & P. Orero (Eds.), Audio description (pp. 159-178). John Benjamins.

Matamala, A. (2014). Audio describing text on screen. In A. Maszerowska, A. Matamala, & P. Orero (Eds.), Audio description: New perspectives illustrated (pp. 103-120). John Benjamins.

Mazur, I. (2014). Gestures and facial expressions in audio description. In A. Maszerowska, A. Matamala, & P. Orero (Eds.), Audio description: New perspectives illustrated (pp. 180-197). John Benjamins.

Mazur, I. (2020). Audio description: Concepts, theories and research approaches. In Ł. Bogucki & M. Deckert (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of audiovisual translation and media accessibility (pp. 227-247). Palgrave Macmillan.

Perego, E. (2024). Audio description for the arts: A linguistic perspective. Routledge.

Romero Fresco, P. (2019). Accessible filmmaking: Integrating translation and accessibility into the filmmaking process. Routledge.

Rubio, M. L. (2024). An approach to audio description of humour in different cultural settings. Estudios de Traducción, 14, 133-142.

Sanz-Moreno, R. (2018). Audio description of taboo: A descriptive and comparative approach. SKASE Journal of Translation and Interpretation, 11(1), 92-105.

Snell-Hornby, M. (1988). Translation studies: An integrated approach. John Benjamins.

Soler Gallego, S. (2019). Defining subjectivity in visual art audio description. Meta, 64(3), 708-733. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.7202/1070536ar

SPECIAL VIEW. (2021). Turn the sound on: sound descriptions for silent films. Retrieved from https://en.specialviewportal.ru/articles/articles1152

Starr, K., & Braun, S. (2021). Audio description 2.0: Re-versioning audiovisual accessibility to assist emotion recognition. In S. Braun & K. Starr (Eds.), Innovation in audio description research (pp. 97-120). Routledge.

Stevens, N., & Clare, J. (2014). The challenges of audio describing silent films. Retrieved from https://www.redbeemedia.com/blog/the-challenges-of-audio-describing-silent-films/

Szarkowska, A., & Orero, P. (2014). The importance of sound for audio description. In A. Maszerowska, A. Matamala, & P. Orero (Eds.), Audio description: New perspectives Illustrated (pp. 121-139). John Benjamins.

Taylor, C., & Perego, E. (2022). Introduction. In C. Taylor & E. Perego (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of audio description (pp. 1-10). Routledge.

United Nations. (1948). Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights

Vercauteren, G. (2007). Towards a European guideline for audio description. In J. Diaz Cintas, P. Orero, & A. Remael (Eds.), Media for all: Subtitling for the deaf, audio description, and sign language (pp. 139-149). Rodopi.

Vercauteren, G., & Reviers, N. (2022). Audio describing sound–what sounds are described and how?: Results from a Flemish case study. Journal of Audiovisual Translation, 5(2), 114–133. https://doi.org/10.47476/jat.v5i2.2022.232

Yus, F. (2016). Humour and relevance. John Benjamins.

Zabalbeascoa, P., & Attardo, S. (2024). Humour translation theories and strategies. In L. Kostopoulou & V. Misiou (Eds.), Transmedial perspectives on humour and translation (pp. 13-32). Routledge.

Filmography

Road Runner (Chariots of Fur). 1994. Directed by Chuck Jones. USA. Persian AD by Mahale Nabinayan.

Shaun the Sheep. 2007-2020. Directed by Richard Webber. UK. Persian AD by Sevina.

The Pink Panther. 1969–1980. Directed by Hawley Pratt. USA. Persian AD by Sevina.

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable in this article.

Disclaimer

The authors are responsible for obtaining permission to use any copyrighted material contained in their article and/or verify whether they may claim fair use.

∗ ORCID 0009-0009-3015-5082, e-mail: masoomeh-helal_brjnd2021@birjand.ac.ir↩︎

∗∗ ORCID 0009-0003-0157-839X, e-mail: hemami@birjand.ac.ir↩︎

∗∗∗ ORCID 0000-0001-7706-0552 email: s.ameri@birjand.ac.ir (Corresponding Author)↩︎

Notes

sevinagroup.com↩︎

gooshkon.ir↩︎

Due to copyright laws and fair use, the number of scene images had to be minimised. For a better understanding of the analysis, readers are encouraged to watch the relevant scenes via the provided YouTube links.↩︎

The original version can be accessed at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4n4uf51XwXg↩︎

The original version can be accessed at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0LcgsWh-SB0↩︎

The original version can be accessed at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hFAZH0-f4q4↩︎