Dubbing and reception: The revival of Chinese dubbese as internet memes on social media

Xuemei Chen1, Lingnan University

ABSTRACT

Chinese dubbese, a stylised register of Mandarin used in dubbed audiovisual content, originated in the pre-digital era but has recently undergone an unexpected revival on social media platforms. While existing research has focused on dubbese’s formal linguistic features, this study shifts the focus to its circulation, reception, and various functions in participatory digital culture. Drawing on a curated corpus of highly viewed dubbese-themed videos and user comments from Bilibili, China’s most popular video-sharing site, this article uses a qualitative analysis to examine how online audiences reappropriate dubbese as a memetic and performative linguistic resource. The findings challenge the prevailing assumption in audiovisual translation studies that audiences prioritise linguistic naturalness in dubbing. Instead, users embrace dubbese for its stylised foreignness, nostalgic resonance, and playful aesthetic, transforming it into a source of affective engagement and internet humour. Dubbese expressions function as both reusable phrasal templates and widely circulated catchphrases, revealing how language from dubbed media is revitalised as internet memes. By situating dubbese within the framework of internet memes and online subcultures, this study contributes to ongoing debates in audiovisual translation studies, and calls for a reassessment of how dubbed language operates in contemporary digital life.

KEYWORDS

Dubbese, dubbing, internet memes, reception, online subculture.

Introduction

Since the release of Private Aleksandr Matrosov (1947), the first Chinese dubbed Soviet film in 1949, dubbing played a central role in the translation of foreign audiovisual content in China for several decades. Its influence grew steadily from the 1950s through the 1970s and reached a cultural apex in the 1980s, a period often referred to as dubbing’s “golden age” (Ma, 2005, p. 3). However, with the rise of subtitling in the late 1990s and early 2000s, particularly among younger audiences, the popularity of dubbing began to wane. Subtitled content became associated with authenticity and immediacy, while dubbed products came to be seen as outdated, even nostalgic artefacts of “a bygone era” (Du, 2018, p. 285).

Yet in the digital age, an unexpected revival has occurred: Chinese dubbese, the distinctive linguistic register of dubbed audiovisual products, has resurfaced as a vibrant discursive resource on social media platforms. No longer confined to the screen, dubbese has been reimagined by internet users who imitate, parody, and remix its language in videos, comments, and memes. This resurgence challenges the prevailing assumption in audiovisual translation studies that audiences primarily value linguistic naturalness in dubbing (Chaume, 2020; Taylor, 2020). Instead, this study argues that dubbese’s perceived artificiality and stylisation are precisely what make it appealing in online contexts, where it is celebrated as a shared cultural artifact, a vehicle of humour, and a tool for identity performance.

Dubbese, often described as the “register of dubbing,” exhibits distinct features at the phonetic, morphological, syntactical, and lexical levels (Chaume, 2020, p. 115). It has also been called “dubbing translationese” (Duff, 1989) or “audiovisual translationese” (Chaume, 2004). Pavesi conceptualises dubbese as “a third norm” (1996, p. 128) that deviates from both source and target languages to form a stylised linguistic system (Bucaria, 2008, p. 162). Dubbese “keeps reinforcing its repertoire of formulae, translational clichés, and other examples of formulaic language through repeated use” (ibid.). These studies have primarily focused on dubbese’s formal linguistic features. However, little attention has been paid to how dubbese is received, appropriated, and recontextualised by audiences in participatory digital culture.

This article addresses this gap by analysing the memetic reappropriation of dubbese on Bilibili, China’s most influential video-sharing platform. On Bilibili, users do not merely consume dubbese — they interact with it, mimic it, and transform it into an expressive and affective resource. This participatory engagement aligns with the dynamics of internet memes. Shifman (2014), building upon Dawkins’ (1976) original concept of meme, defines an internet meme as “(a) a group of digital items sharing common characteristics of content, form and/or stance; (b) that were created with awareness of each other; and (c) were circulated, imitated, and/or transformed via the Internet by many users” (Shifman, 2014, p. 41). While Dawkins emphasises replication and stability of memes (1976, p. 206), contemporary internet memes are dynamic, participatory, and shaped by human creativity (Jiang & Vásquez, 2020). Framing dubbese as an internet meme provides a powerful analytical lens through which to understand its unexpected digital revival. This perspective not only traces the circulation and transformation of translation language in online spaces but also reveals how users recontextualise dubbese to express humour, nostalgia, identity, and subtle resistance. The meme framework thus illuminates the social and semiotic dynamics underpinning dubbese’s reemergence in the digital era.

This study investigates how Chinese netizens creatively imitate and parody dubbese on Bilibili. It seeks to answer two questions: What are the linguistic characteristics of the most used Chinese dubbese on Bilibili? Why has dubbese gained renewed popularity among Chinese netizens in the digital age? Through these questions, this study contributes to an evolving body of work at the intersection of audiovisual translation, digital sociolinguistics, and media studies, showing how translation language is not only recontextualised online, but also aesthetically and socially revalued. Methodologically, this research adopts a qualitative approach, analysing a curated corpus of highly viewed dubbese-themed videos and their accompanying comments on Bilibili. This corpus allows for both linguistic analysis of dubbese expressions and thematic analysis of user reception and engagement.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows: Section 2 situates the present study within existing research on dubbese and internet memes, followed by a detailed description of data collection and the analytical method in Section 3. Section 4 presents the key lexical and syntactic features of commonly used dubbese expressions on Bilibili, and explores user motivations behind their adoption. Finally, the article discusses the broader implications of dubbese’s memetic revival for translation studies and digital culture.

Relevant studies on dubbese and internet memes

While extensive research has been conducted on the features of dubbese in Western contexts (Bucaria, 2008), relatively few studies have examined the uniqueness of Chinese dubbese beyond its phonetic features. Hou et al. (2012) argue that dubbed Chinese has evolved into an artistic and artificial form of Mandarin, distinct from both standard spoken Chinese and the source language. By comparing the acoustic features of standard Chinese, dubbed Chinese, and English, they find that the rise-fall intonation used in dubbed Chinese to express “Yes” (in contrast to the falling intonation in Mandarin) closely resembles the original English expression. Du further highlights the phonetic idiosyncrasies of Chinese dubbese, noting that dubbing actors often speak with a kind of “foreign accent” (2018, p. 287). As she explains, they are “forced into drawls, prestos, paddings, and unnatural pauses unheard of in everyday Mandarin” (ibid.). She also identifies elements of “heightened theatricality” and subtle traces of regional dialect (Du, 2018, p. 288). While these studies offer valuable insights into the phonetic dimensions of Chinese dubbese, little attention has been paid to its lexical and syntactic features, leaving a significant gap in the literature.

Beyond linguistic features, some scholars have examined the reception of Italian dubbese and its potential influence on real-life language use. Bucaria and Chiaro (2007), for example, conducted a reception study of nine dubbed Italian expressions, surveying the public, journalists, academics, and dubbing professionals. They reveal that while audiences, particularly frequent consumers of dubbed and homemade products, recognise and accept these expressions, they are unlikely to use them in everyday speech (p. 115). This study suggests that dubbese is often seen as inauthentic, though socially recognizable. In a follow-up study, Bucaria (2008) obtained similar results, showing that Italian audiences view Anglicisms and formulaic language in dubbese as improbable in natural Italian. However, she raises the critical question of “to what extent dubbese is affecting and will continue to affect the language of future dubbed and even non-dubbed products” (p. 162). Antonini also notes concerns among Italian screen professionals that dubbese may negatively impact children’s acquisition of authentic spoken Italian (2008, p. 136). While these studies focus on Italy, there remains a lack of research specifically examining the influence of Chinese dubbese on language use in China. This study addresses this gap by analysing the use of Chinese dubbese on social media platforms, particularly Bilibili, where dubbese has emerged as a popular form of internet meme.

Internet memes occur in a variety of forms, including phrasal templates, catchphrases, image macros, and initialisms (Zappavigna, 2012). Phrasal templates refer to “formulaic sentence patterns with slots allowing content to be changed” (Willmore & Hocking, 2017, p. 141). One example is “I don’t always X, but when I do, I Y,” which can be adapted to various contexts (see Wiggins, 2019). Catchphrases, by contrast, are fixed, repeatable expressions (Willmore & Hocking, 2017, p. 141), such as “我想静静” [I want to calm down/leave me alone] (see Guo, 2018). Image macros, arguably the most visually recognizable meme type, consist of “an iconic static image overlaid with a humorous written text” (Willmore & Hocking, 2017, p. 141). The typical example includes the Distracted Boyfriend meme (see Scott, 2021), where the same image is reused with different captions to generate new meanings. Initialisms involve abbreviating phrases into their first letters, such as LOL (“laugh out loud”) or FOMO (“fear of missing out”), which function as memes through their widespread cultural resonance and repetition.

Research into internet memes covers wide-ranging topics, such as humour conveyed through memes (Vásquez & Aslan, 2021), their intertextuality (Wiggins, 2019), the verbal and visual rhetorical techniques (e.g., metaphor, simile, synecdoche, metonymy, pastiche, and wordplay) used in their creation and interpretation (Huntington, 2016), the socio-political messages they embed (Fang, 2020), as well as social bonding and collective identities they can build (Katz & Shifman, 2017). Most of these studies focus on image macros due to their simplicity, humour, and visual appeal (Ross & Rivers, 2017, p. 2). They are often considered the most “malleable” subcategory of internet memes (Wiggins, 2019, p. xv). However, other types of memes, especially text-based memes, also deserve scholarly attention, particularly in non-Western contexts.

In Chinese, the term “internet meme” is commonly translated as “网络梗” [Internet meme] or “表情包” [facial expression package/emoji pack]. The former aligns with the broader definition of internet memes, referring to widely shared phrases, jokes, or cultural references. The latter typically refers to images or stickers — often featuring facial expressions — with or without accompanying text, resembling the image macro category of memes (see Jiang & Vásquez, 2020). In this article, the term “internet memes” specifically refers to text-based memes, with a focus on two subtypes: phrasal templates (reusable sentence structures) and catchphrases (short, repeatable expressions). This focus allows for a more targeted analysis of how Chinese dubbese operates within the framework of internet meme culture. By examining the structure, usage, and reception of dubbese-based memes, the study offers new insight into the intersection of dubbing, digital language play, and participatory culture.

Data collection and analytical method

The study is based on two datasets collected from Bilibili, China’s most popular video-sharing platform, which functions as both a site of audiovisual remix and digital discourse. A report by Bilibili reveals that the number of its monthly active users (MAU) in the third quarter of 2023 reached 341 million and that 82% of its users were born between 1990 and 2009 (Lanshiwendao, 2023). Originally cantered around ACG (anime, comics, and games) content, Bilibili has evolved into a comprehensive video-sharing website, encompassing various genres such as entertainment, knowledge, and fashion. The site offers interactive features including danmu chats (see Chen, 2023a), webpage commentaries, sharing, following, likes, and favourites.

This study adopts a qualitative method to explore how dubbese is used and discussed in participatory online culture. On 6 May 2024, I conducted a keyword search for “译制腔” [dubbese] on Bilibili without applying any filter priority. The search returned many video results (Bilibili, 2024). From these, I selected the first eight videos to analyse the lexical and syntactic features of commonly used dubbese. These videos, uploaded between 2019 and 2024, each attracted millions of views and showcased dubbese in various creative forms, such as fundubs (humorous dubbings) of Chinese TV series and funny imitations of everyday speech styles. Table 1 provides key metadata about these videos. The titles are my English translations from Chinese. For ethical reasons, screennames of video uploaders were excluded.

| Video number and title | Uploaded date | Number of views (million) |

Number of comments | Main content |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. “Watch Huaqiang buying melons in dubbese” | 4 March 2024 | 1.422 | 1625 | The video (01: 57 minutes) uses dubbese to fundub one clip in which the character Huaqiang Liu buys watermelons from Vanquish [征服] (2003), a modern Chinese TV program about crime. |

| 2. “What if Liang Zhuge had scolded Minister Wang in dubbese?” | 4 October 2020 | 1.855 | 1740 | The video (02: 26 minutes) uses dubbese to fundub one clip of the historical Chinese TV series Romance of the Three Kingdoms [三国演义] (1994), which is adapted from the classic 14th-century novel of the same title. |

| 3. “Imagine Empresses in the Palace... but in dubbese!” | 15 March 2020 | 1.096 | 2565 | The video (01: 54 minutes) uses dubbese to fundub one clip of the Chinese costume TV drama series Empresses in the Palace [甄嬛传] (2011). |

| 4. “What if a shop assistant spoke in dubbese? Hahaha!” | 22 November 2019 | 2.732 | 2472 | The video (01: 11 minutes) uses dubbese to imitate a conversation between a shop assistant and a customer about buying lipstick. |

| 5. “Where does dubbese come from, and why does it sound so unusual?” | 20 June 2020 | 1.218 | 7700 | The video (04: 39 minutes) explains the historical background and features of dubbese with examples. It analyses its strengths and weakness. |

| 6. “What if everyone spoke in dubbese?” | 6 September 2020 | 1.685 | 2094 | The video (02: 15 minutes) shows people speaking dubbese in various scenarios of daily life. |

| 7. “Watch Journey to the West in dubbese!” | 15 August 2020 | 3.411 | 3852 | The video (02: 00 minutes) uses dubbese to fundub one clip of the Chinese mythology TV series Journey to the West [西游记] (1982), which is adapted from the classic 16th-century novel of the same title. |

| 8. “What would it be like to teach a class in dubbese.” | 19 September 2020 | 2.281 | 6629 | The video (02: 15 minutes) shows a classroom scene where the teacher and students, portrayed as cartoon characters, communicate using dubbese. |

Table 1. Metadata of the top eight videos.

The first stage of analysis involved close viewing of the eight videos and transcription of relevant segments to identify linguistic features and patterns characteristic of dubbese. However, tracing the exact origin of these features proved challenging, as many dubbese elements, such as metaphors or exaggerated expressions, may originate from user-generated parodies rather than professional dubbing. This recognition shifts the analytical focus from dubbese as a static linguistic product to dubbese as a participatory, evolving register shaped by online communities.

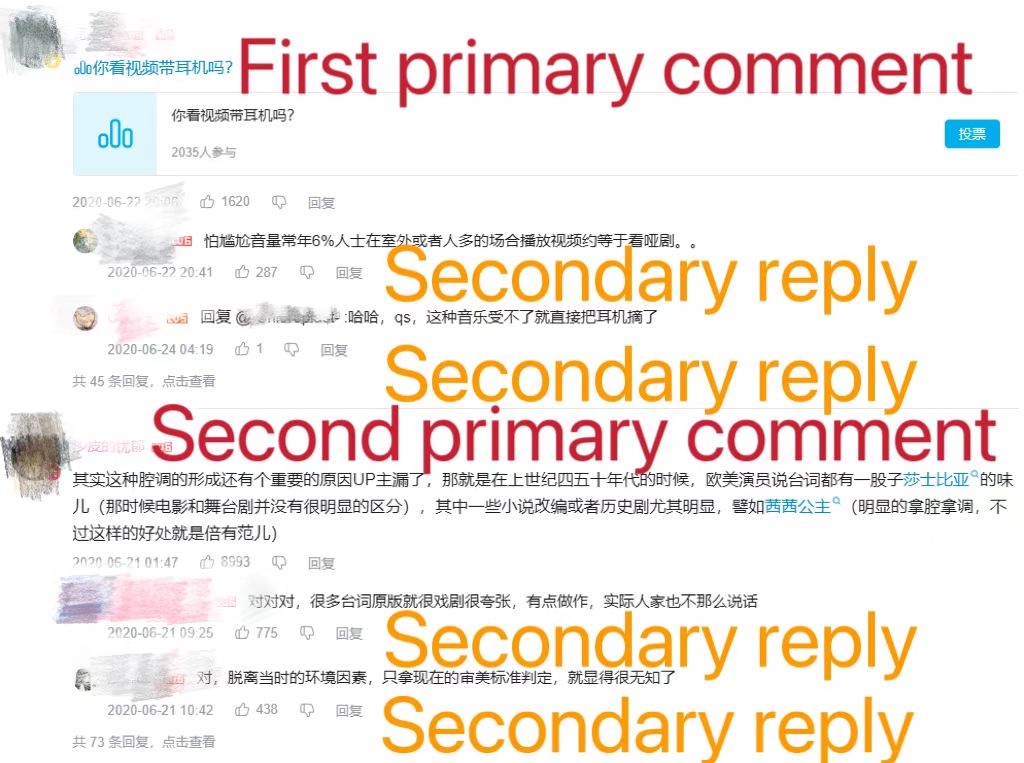

The other dataset consists of the webpage commentary on the fifth video, titled “Where does dubbese come from, and why does it sound so unusual?” This video explicitly examines the history and features of dubbese and attracts the most relevant comments among the eight videos. As of 6 May 2024, this video received 7700 comments in total in its webpage, including 2326 primary comments (direct responses to the video) and 5374 secondary replies (responses to 224 primary comments). Figure 1 shows the hierarchical presentation of the commentary of the fifth video.

Figure 1: Example legend

Figure 1. The presentation of first and second primary comments in the commentary of the fifth video.

The second stage of analysis was to examine how users discuss dubbese in the commentary of the fifth video. To this end, I conducted multiple rounds of close reading and thematic filtering, extracting 1232 comments (both primary and replies) that directly addressed dubbese. For instance, I excluded the first primary comment, which asked viewers whether they wear headphones when watching videos, as well as its replies (see Figure 1), as they were unrelated to dubbese. In contrast, I retained the second primary comment, which offered an additional explanation for the formation of dubbese and sparked a more focused conversation on the topic. These 1232 relevant comments can be grouped into two thematic categories: user attitudes toward dubbese (750 comments), and user attempts to imitate or parody dubbese (482 comments).

Informed by previous online reader reception studies (Chen, 2023b, 2024), the last stage of analysis involved using a thematic analysis approach (Braun & Clarke, 2006) to code these 750 comments in order to understand users’ attitudes towards dubbese. Thematic analysis is “a method for identifying, analysing and reporting patterns (themes) within data” (p. 79). I first manually coded 750 comments by tagging keywords and summarising their main ideas, generating a list of codes (see Figure 2). Each comment often serves as a coding unit, with a single comment sometimes containing multiple codes. These codes were then grouped into three main themes: positive, negative, and mixed. To ensure the coherence and consistency of the themes, I cross-referenced them and compared them to the original comments. This careful review process led to a relatively comprehensive thematic description of the comments, which will be discussed in the next section.

Figure 2. Screenshot of the coding process (the red highlights are the keywords; the blue parts are the codes for each comment; the parts in square brackets are my English translations).

Studying online user comments is methodologically significant because it allows access to how ordinary users reflect on and participate in the shaping of dubbese as a cultural and linguistic phenomenon. Unlike interviews or surveys, these naturally occurring interactions provide insights into authentic, in-the-moment metalinguistic practices and community ideologies (Kotze, 2024). The reply structure also allows us to trace how ideas are received, debated, and reframed within the digital public sphere (Chen, 2023c). Meanwhile, this approach comes with limitations. Interpretation of irony or sarcasm in written comments by anonymous users can be challenging. Nonetheless, this method offers a valuable window into how dubbese is talked about, contested, and playfully performed by online communities.

Results

4.1 Common lexical and syntactic features of dubbese

Based on the eight videos and webpage commentary on the fifth video, this study finds that the most used features of dubbese fall into the categories of interjections, intensifiers, pronouns, and swear words (see Table 2). These elements are known as “orality markers” (Baños, 2013, p. 526), which are typically found in fictional dialogues. They aim to create a sense of naturalness and authenticity within dubbed content. However, it has been observed that some of these markers are often overused in dubbing. For instance, Bruti and Pavesi (2008) identify a tendency to overuse Italian interjections that share phonological and pragmatic similarities with their English counterparts. Pavesi (2009) also notes that while the first- and third-person pronoun occur less frequently, the second-person pronoun appears more frequently in dubbing than in spontaneous Italian conversation. Furthermore, Baños points out that the excessive use of adverbial intensifiers may reveal the artificial and rehearsed nature of fictional dialogue (2013, p. 530). The overuse of certain linguistic choices may stem from the formulaic nature of dubbed productions (Pavesi, 2016). This repetition can leave a lasting impression on the audience, so much so that they may remember and even imitate these linguistic patterns in their own speech.

| Category | Examples |

|---|---|

| Interjections | 哦, 我的上帝呀/啊 [oh, my god]; 哦, 天呐 [oh, god]; 哦, 亲爱的 [oh, dear]; 哦不,亲爱的 [oh, no, dear] |

| Intensifiers | 真 [really]; 简直 [virtually]; 太 [too]; 极了 [too];透了[too];狠狠地 [strongly];大大 [too] |

| Pronoun | 我的……[my…]; 你 [You]; 这 [This/It] |

| Swear words | 见鬼 [damn it]; 该死 [damn it] |

| Metaphor/simile | 你这愚蠢的土拨鼠 [You, stupid marmot]; 你这可笑的牛粪 [You, ridiculous cow dung]; 这简直就像隔壁大妈做的苹果派一样糟糕 [This is simply as terrible as the apple pie made by the auntie next door] |

| Others | 发誓 [swear]; 踢屁股 [kick the ass]; 老伙计 [old man/buddy] |

Table 2. Summary of the mostly used dubbese.

The use of metaphor and simile in memes represents another fruitful category, often giving rise to widespread online imitations and parodies. These expressions often involve the juxtaposition of absurd pairs between tenors (the entities being described) and vehicles (the figurative constructs used to characterise them), resulting in unexpected and humorous effects. This creative approach captivates users, enticing them to contribute their own comical and witty comparisons, where the tenors often include pronouns like “you,” “it,” or “this.” As will be elaborated below, in the comment section, posters frequently engage in playful competitions to generate increasingly absurd or surprising vehicles for their metaphors and similes. This form of imitation serves as “an exercise in the display of wit, often involving an element of self-indulgence” (Zappavigna, 2012, p. 126). The focus lies less on the literal meanings of the expressions and more on creatively manipulating recognised templates. Huntington (2016) demonstrates that metaphor and simile are prevalent in meme creation, and their inherent humour contributes to their viral spread. Meme creators often build upon each other’s creations for comedic effect (Willmore & Hocking, 2017, p. 145), and users in turn tend to share memes they find funny with others (Zappavigna, 2012, p. 126).

4.2 Reasons for the adoption of dubbese

The second dataset, which consists of webpage commentary on the fifth video, is used to explore why people tend to adopt dubbese in cyberspace. Table 3 presents the coding results of the 750 comments reflecting posters’ attitudes towards dubbese. As ten comments contain two codes, the total number of codes exceeds the number of comments by ten.

| Category | Theme | Code (frequency) | Total number |

|---|---|---|---|

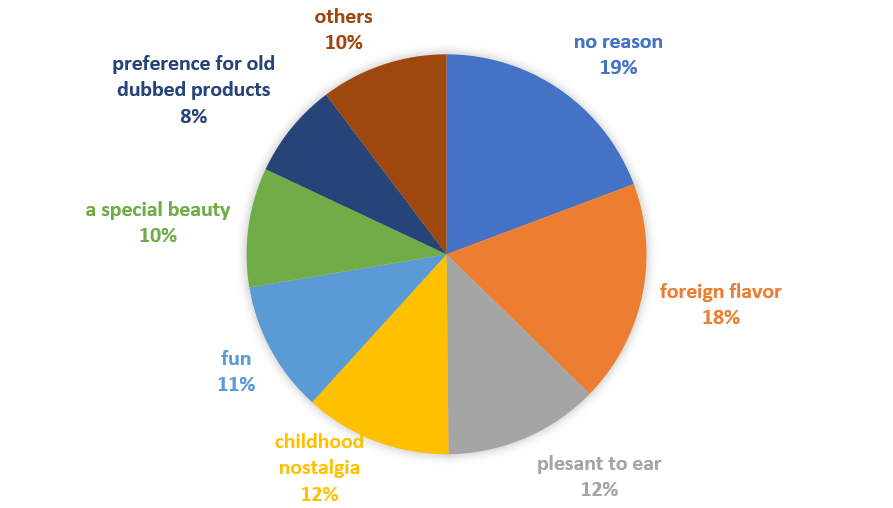

| Attitude | positive | no reason (120), foreign flavour (112), pleasant to ear (78), childhood nostalgia (74), fun (66), a special beauty (60), preference for old dubbed products (48), and others (64) | 622 |

| negative | sounds uncomfortable and terrible (52), sounds strange (24), sounds emotionless (12), others (24), and no reason (22) | 134 | |

| Mixed | awkward yet funny (4) | 4 | |

| Total | 760 | ||

Table 3. Summary of webpage commentary on the fifth video.

The positive attitudes expressed in these comments offer insight into the motivations behind the adoption of dubbese. These reasons include “foreign flavour,” “pleasant to ear,” “childhood nostalgia,” “fun,” “a special beauty,” and “preference for the old dubbed products.” The distribution of these categories is illustrated in Figure 3. To provide a more focused and coherent description and analysis, the codes of “pleasant to ear” and “a special beauty” have been combined, so have “childhood nostalgia” and “preference for the old dubbed products.”

Figure 3. Percentages of posters’ positive attitudes towards dubbese.

4.2.1 Foreign flavour and immersive cinematic experience

A total of 112 comments (18%) appreciates dubbese for its exotic flavour, which enhances the immersive experience of watching films. This aligns with Yang and Ma’s view that traditional approach to dubbing, particularly by the Shanghai Film Dubbing Studio, is characterised as “Chinese tinged with a foreign flavour” (2010, p. 34). The dubbing philosophy of the studio, as summarised by its former head Xuyi Chen, emphasises that “[t]he script translation should reflect the flavour, and the dubbing performance should convey the spirit” (Sun, 2008, p. 34). Voice actress Xiu Su further explains: “Why did people think our dubbing, which was standard Mandarin, had a foreign flavour? It was because we strove to adhere to the characters” (Lu, 2009).

Viewers often associate the sound of dubbese with the foreignness of films, alongside other foreign elements like the actors’ appearances and body language. Rather than distancing the viewers, this perceived foreignness contributes to a more immersive viewing experience. This sentiment is further illustrated by three comments2:

The greatest advantage of dubbese lies in its ability to preserve the ‘cultural peculiarities’ and ‘original sound’ of the source language. This harmony between audio and visual elements surpasses [the mismatch] that would occur with authentic Chinese language and visuals. The same is true for the weird tone of [dubbese]. English has many intonations. It would be jarring if the language of dubbed films conformed to Chinese conventions (22 July 2020).

The localised dubbed products are unlike foreign films, lacking a feeling of ‘distance creates beauty’… Dubbese stands out with its distinct linguistic and aesthetic system, exemplified by dubbing actor Zirong Tong. It is very interesting. Upon hearing it, Chinese audiences immediately recognise the foreign origin of the films they are watching. This sense of distance allows audiences to fully immerse themselves in the viewing experience (21 July 2020).

It is undeniable that dubbese is an exceptional artistic creation by the earlier generation of [dubbing actors]. Dubbese, with its foreign flavours, matches the [on-screen] actors without causing any dissonance. It also adapts exaggerated emotions to suit the Chinese audience’s preferences. I did not encounter the line ‘stupid marmot’ mentioned in the [fifth] video (21 August 2020).

The preference for dubbese’s foreign flavour invites reflection on how foreignness is received by viewers. As the second post suggests, to avoid jarring some audiences, dubbed content may need to retain some degree of distinctiveness from domestic productions. The presence of dubbese contributes to a sense of authenticity, as traces of foreignness are perceived as more reliable (see Hu, 2022, p. 215). Several users express that it would be awkward or unnatural if the dubbed actors spoke standard Mandarin. For example,

I think dubbese is interesting. It would be abrupt if the standard Mandarin were used to dub the non-local actors and lifestyle…Dubbese with a slightly foreign accent matches the foreign lifestyle. We can recognise that the film is not domestic just by hearing dubbese (27 August 2020).

These reflections suggest that authentic Chinese language may not be compatible with foreign films, and that this incompatibility can enhance the sense of foreignness, sometimes even contributing to a funny effect. This echoes Koskinen’s argument that excessive domestication may lead to a “rather comical foreignising effect” (2000, p. 61) in her analysis of the Commission of the European Union’s institutional translation. Yang and Ma also argue it is important to avoid over-localizing Chinese in dubbing (2010, p. 58). They highlight that the use of local expressions, such as idioms and slang, not only risks sounding jarring or unintentionally comical but also disrupts the immersive cinematic experience (ibid.).

While scholars such as Romero-Fresco (2009) and Pérez-González (2007) have primarily focused on the (un)naturalness of dubbese, they have largely overlooked how audiences receive and interpret this linguistic style. Audiovisual translation studies often operate under the assumption that audiences expect linguistic naturalness in dubbing (Chaume, 2020; Taylor, 2020). However, this study reveals that rather than perceiving the stylised and foreign-sounding language of Chinese dubbese as a flaw, many viewers embrace its unnaturalness — sometimes precisely because it departs from everyday speech. This reception suggests that dubbese can function not as a failed attempt at naturalism, but as a distinct aesthetic form that audiences appreciate.

This finding invites a rethinking of notions like the “suspension of linguistic disbelief” (Romero-Fresco, 2009) and “suspension of prosodic disbelief” (Sánchez-Mompeán, 2020). While both scholars argue that audiences may overlook the artificiality of dubbing to preserve narrative immersion, the responses examined in this study suggest a more complex dynamic: viewers are not merely tolerating the unnaturalness of dubbese but are actively celebrating it. In this sense, dubbese becomes a site of playful engagement and stylised performance, rather than a barrier to immersion. Recognising this shift calls for a broader understanding of what constitutes viewer satisfaction and authenticity in dubbed media.

4.2.2 Pleasant sound quality and aesthetic appreciation

78 comments (12%) like dubbese for its pleasant, comfortable, and catchy sound quality and intonation. This favourable auditory experience is often associated with a perceived “a special beauty” of dubbese, as expressed by another 60 posters (10%). Below are five illustrative comments that highlight this perspective:

I enjoy listening to the dubbese in old films produced by Shanghai Film Dubbing Studio. The dubbing actors have a pleasing tone that sounds comfortable (24 August 2020).

Some dubbese sounds great. I’m not referring to the sound quality specifically, but rather the overall tone. A prime example is when romantic and poetic language is dubbed. Using dubbese to deliver elegant and slow lines feels like reciting Shakespearean poetry. However, using dubbese to dub The Big Bang Theory may result in hilarity (21 June 2020).

The dubbed products by Shanghai Film Dubbing Studio sound amazing. The dubbese matches the dramatic essence of the original films (22 June 2020).

I like dubbese because it possesses a unique beauty. It’s a delight to listen to the distinct accents of the skilled dubbing actors (9 July 2020).

It is the sound that attracts me. The voices of the dubbing actors are even better than those of the original actors (20 June 2020).

Yang and Ma argue that dubbed voices often sound better than the original due to physiological differences: Westerners typically have deeper voices due to thicker vocal cords, while Chinese voices are higher and thinner (2010, p. 62). Hence, original foreign voices may sound “vague and slightly hoarse,” whereas dubbed voices are perceived as “full, resonate, and articulate” (ibid.). For example, Feng Liu, the current director of the Shanghai Film Dubbing Studio, stated that the actor Alain Delon in Zorro (1975) has a husky voice, fitting Western rugged aesthetics. So, the former director of the studio, Xuyi Chen, chose Zirong Tong to dub Delon, believing that Tong’s refined and elegant voice aligns with the Chinese romantic imagination of a hero (Wang, 2017).

The primary comment, “Why do I sense a special beauty in dubbese?!” (21 June 2020), sparked a threaded discussion with 31 replies, 16 of which explicitly express agreement with the sentiment. Among these replies, three posters emphasise the theatrical quality of dubbese, noting that it possesses a style reminiscent of stage performance. Yang and Ma also observe that dubbing actors are professionally trained and skilled in stage language (2010, p. 113). Many dubbing actors in the Shanghai Film Dubbing Studio have a background in theatre performance, including Yuefeng Qiu, Zi Li, Zirong Tong, and Lei Cao. Their training allows for clear articulation and versatile intonation, enabling them to adapt dubbese to a wide range of characters and genres.

4.2.3 Fun, humour, and language play

Another 66 comments (11%) describe dubbese to be playful, hilarious or addictive. Examples include:

I like dubbese because it is humorous (21 June 2020).

We joke about dubbese because it is funny (7 July 2020).

The more you listen to dubbese, the more addicted you become (6 July 2020).

In the webpage commentary of the fifth video, 482 comments imitate or parody dubbese, showcasing its highly memetic and playful nature. Commonly expressions used in these comments include “哦!老天”/ “噢,我的上帝啊”/ “哦, 天呐”/ “噢, 天啊” [oh, my god], “我发誓” [I swear], “狠狠地踢屁股” [kick the ass hard], “老伙计” [old man/buddy], 该死 [damn it], and “愚蠢的土拨鼠” [stupid marmot]. These expressions show the creative and formulaic nature of dubbese, which invites playful imitation. As Shifman suggests, such playfulness encourages user creativity and participation in language games (2011, p. 196).

Interestingly, three posters summarise the “formula” of dubbese, listing recurring phrases such as “上帝” [God], “老伙计” [old man/buddy], “该死” [damn it], “踢屁股” [kick the ass], “oh,” and “我发誓” [I swear] (6 June 2020). These catchy templates serve as a base for numerous derivatives. The most-liked primary comment (13,443 likes) is a vivid parody of dubbese:

Oh, my god, if I have the damn virtual coins, I will give them to you. I swear to St. Mary I will do that. Of course, sometimes one’s wish cannot come true, my child. The fact is that I don’t have virtual coins. I swear I don’t. This feeling is just like adding ketchup to Oreo, both happy and painful. Yeah, that’s right, you know, both happy and painful (20 June 2020, my italics for dubbese expressions).

This post incorporates typical dubbese phrases such as “哦,我的上帝呐” [oh, my god], “该死的” [damn], “发誓” [swear], and a humorous simile “像给奥利奥里加了番茄酱” [like adding ketchup to Oreo]. This primary comment garnered 119 replies, including 40 replies written in dubbese, testifying to its viral and memetic appeal. Dubbese meets Shifman’s (2014) criteria for internet memes: it consists of texts sharing a recognizable formula, created with an awareness of each other, and circulated, imitated, and transformed by many users online.

Humour is a prominent feature of many internet memes, contributing to their viral proliferation (Shifman, 2011; Willmore & Hocking, 2017; Vásquez & Aslan, 2021). It is often produced by “an unexpected cognitive encounter between two incongruent elements” (Shifman, 2014, p. 79). In the case of dubbese, various forms of incongruity are present in the top eight dubbese-themed videos and comments: “ancient” dubbese is applied to a modern context; on-screen “dubbese” is used in daily communication (e.g. shopping); and dubbese is used to dub Chinese historical TV series, creating audio-visual incongruity. These unexpected combinations generate comical effects. Besides, many examples of dubbese themselves are humorous, involving expressions that are simply “absurd” yet “catchy” (Zappavigna, 2012, p. 101). The anomalous juxtapositions in metaphors and similes create humour and inspire further playful adaptations. Users can repeat dubbese as catchphrases or create their own based on phrasal templates. In both cases, language play fosters a sense of belonging within the subcultural community.

However, this light-hearted use of dubbese has sparked criticism. Some posters argue that the internet parody of dubbese disrespects seasoned dubbing actors and diminishes the artistic value of dubbing. For example:

Dubbese became popular because influencers imitate it with weird accent and intonation. I haven’t encountered the dubbed lines ‘stupid marmot’ and ‘kick the ass hard’…Translators would not produce such terrible translations. Please do not equal these to professional dubbing (29 October 2021).

This backlash reflects a tension between subcultural language play and professional artistic standards. While dubbese was initially embraced as a fun, creative trend, its popularity as a meme has led some to worry that it trivialises the art of dubbing. This clash underscores the complex dynamics of online subcultures, where humour, imitation, and innovation coexist — and sometimes conflict — with cultural and artistic values.

4.2.4 Nostalgia for the old days and classic dubbed products

Another reason for the growing popularity of dubbese is nostalgia associated with classic dubbed products. 74 comments (12%) state that dubbese serves as a connection to cherished childhood memories and a more “beautiful” past. For this group of audience, exposure to dubbed content during their formative years has made dubbese symbolic of a specific era in their lives. Examples include:

I find dubbese comforting, as it reminds me of watching CCTV 6 [Chinese TV channel dedicated to movies] in my childhood (21 June 2020).

I find dubbese to be interesting. Hahaha, it brings back memories of my childhood (5 November 2020).

To be honest, I like dubbese. It has a special beauty and enables me to think of the past (20 June 2020).

Young people born after 2000 or 2010 might prefer watching original films over dubbed products, whereas dubbed products represent a childhood memory for people born during the 1970s and 1980s. Those born after 1990 might be exposed to both original and dubbed products (24 November 2020).

As the last comment suggests, dubbese enthusiasts are often those born in the 1970s and 1980s, a period that coincides with the golden age of Chinese dubbing. Their early exposure to dubbese may have cultivated a lasting preference, highlighting the role of habit in shaping viewer attitudes towards dubbese. This observation aligns with the concept of “habituation” as discussed by Blinn (2009), which explains how repeated exposure can influence preferences between dubbing and subtitling.

Moreover, dubbese-based interaction can foster a collective memory and communal identity, particularly among those who grew up during this era. Zappavigna describes internet memes as “identity markers,” used to signal one’s belonging to a particular subculture (2012, p. 111). Similarly, Gal et al. (2016) discuss how memes help form collective identities and norms within LGBTQ communities. In this context, the adoption and imitation of dubbese may function as a cultural signifier of generational identity, shared values, and common experiences. The use of dubbese not only evokes nostalgic memories but also enables social bonding, as individuals engage in dialogue and reminisce together. In this way, nostalgia plays both a retrospective and prospective role — not only recalling the past but also shaping present interactions (Boym, 2001, p. xvi).

This nostalgia for dubbese and old dubbed products is further intensified by dissatisfaction with current Chinese dubbing. 48 comments (8%) express disappointment with the quality of contemporary dubbed products. For example:

The reason why I do not want to watch current dubbed products is that they do not have the ‘flavour’ of the previous dubbed products. Some current dubbed products are quite jarring (21 June 2020).

Such comments suggest that the preference for dubbese or classic dubbed content is not solely based on technical quality, but also on a nostalgic mindset. This finding aligns with the research by Furno-Lamude and Anderson (1992), who argue that nostalgia can explain why viewers often perceive reruns of familiar programs as superior to new ones. Similarly, this study also echoes Chen’s research on the role of nostalgia in the reception of retranslations. She observes that adults with nostalgic attachments to the old version they read in their childhood tend to prefer it over new translations, even when the retranslation may be superior in terms of semantics or style (2023b, p. 614). Hutcheon argues that nostalgia often involves “an inadequate present and an idealized past” (2000, p. 198). The longing to return to something familiar and comforting can outweigh the appeal of novelty and change, especially when the present is perceived as lacking the emotional depth or artistry of the past.

Dubbese as internet memes and affective communication

The digital revival of dubbese on social media platforms has fostered the emergence of a new online subculture, in which users are bonded by “shared values and cultural practices,” using “symbols and signs to identify with one another” and, to some extent, subverting the norms of mainstream society (Raitanen & Oksanen, 2018, p. 197). Within this subcultural community, the ability to recognise, imitate, and creatively remix dubbese functions as a form of “new” literacy (Knobel & Lankshear, 2007, p. 200), which refers to a culturally situated competence that extends beyond semantic understanding to include stylistic play, intertextual reference, and affective resonance. Users appropriate dubbese as a semiotic resource to construct identity, foster affiliation, and subtly challenge dominant norms of linguistic propriety.

This study builds on prior observations that dubbese phrases have entered the realm of “popular slang” (Jin, 2018, p. 198) or “catchy phrases” (Jin & Gambier, 2019, p. 33), often repeated by Chinese audiences in what Du describes as a form of “second language” acquisition (2018, p. 291). However, rather than treating dubbese merely as linguistic residue from past dubbing practices or as a genre of online communication (see Wiggins, 2019, p. xvi), this article argues that its memetic circulation online has transformed it into a performative and affective discourse, which contains a playful mode of expression that enables emotional release, cultural memory, and social cohesion.

A key finding of this study is that the most frequently used dubbese expressions on Bilibili tend to convey heightened emotional intensity. These include interjections like噢,我的上帝啊 [oh, my god], expletives such as 该死 [damn it], and intensifiers like 极了 [too] and 真 [really]. This pattern can be interpreted in relation to broader cultural norms in Chinese society, where overt emotional expression is often discouraged or deemed socially disruptive (Ma, 2016, pp. 21-22). In this context, dubbese offers a stylised and socially acceptable outlet for emotional catharsis. Its exaggerated tone, comedic delivery, and linguistic foreignness create a safe space for users to vent frustration, share joy, or perform outrage without violating social expectations. This echoes Ma’s (2016) study of rage face memes and Fang’s (2020) work on D’Angelo Dinero’s grinning face memes, both of which highlight the value of unrestrained emotional expressions in Chinese digital culture.

Yet the appeal of dubbese extends beyond emotional release. Like many internet memes, dubbese operates primarily as a tool for social interaction rather than information exchange (Zappavigna, 2012, p. 101). Its value lies not in representational clarity but in its capacity to foster relational ties and signal in-group membership (see Varis & Blommaert, 2015, p. 41). Memes serve as “a powerful social glue,” carrying affective meaning even when lacking clear referential content (Katz & Shifman, 2017, p. 837). This affective meaning is also applied in the case of dubbese. Instead of being used in professional dubbing today or in everyday conversation, dubbese has been embraced by online subcultural communities for purposes of entertainment, play, and nostalgia.

Crucially, dubbese’s revival reveals how translation language can be recontextualised and revalued in participatory digital culture. Rather than fading into obsolescence, dubbese has become a site of creative reappropriation, fuelling the formation of a generational identity rooted in shared memories of dubbed media and collective online engagement. Its memetic afterlife challenges normative frameworks in audiovisual translation that prioritise naturalness (Chaume, 2020; Taylor, 2020), suggesting that audiences can derive pleasure precisely from stylised foreignness and perceived artificiality. In doing so, dubbese exemplifies how translation residues, once considered marginal or outdated, can take on new meaning and vitality in digital subcultures.

Conclusion

While previous studies have focused on analysing the stylistic and linguistic features of dubbese, this research moves further by investigating its circulation, reception, and social functions within online communities. Chinese dubbese, which originated before the digital age, has experienced a resurgence driven by internet users who create videos and share texts imitating or parodying its stylistic features. Drawing on data from Bilibili, this study examines the impact of dubbese on language use in cyberspace. Through qualitative analysis of highly viewed dubbese-themed videos and user comments, the study identifies the lexical and syntactical features of frequently used dubbese expressions, including interjections, intensifiers, pronouns, swear words, absurd metaphors and similes. Online users are drawn to dubbese not only for its foreign charm, pleasing sound, and playful tone, but also for its nostalgic resonance with classic dubbed products. These factors contribute to dubbese’s viral appeal and its transformation into a productive source of internet memes. Some dubbese phrases act as templates, providing users with a pre-existing structure upon which to build new expressions. Others serve as catchphrases, widely imitated and echoed by numerous online users.

This article contributes to the field of audiovisual translation studies by challenging the prevailing assumption that audiences expect linguistic naturalness in dubbing (Chaume, 2020; Taylor, 2020) or try to ignore the artificiality of the dubbed scripts (Romero-Fresco, 2009; Sánchez-Mompeán, 2020). Through an analysis of the reception of Chinese dubbese in online communities, it demonstrates that audiences do not merely tolerate its stylised and artificial qualities but rather actively appreciate and recontextualise them. While existing studies have primarily examined dubbese as a constrained, screen-bound artifact characterised by linguistic unnaturalness (e.g., Hou et al., 2012), this research shows that dubbese has evolved into a dynamic, memetic linguistic form that circulates widely in digital culture. By examining user online comments, this study reveals how dubbese functions not only as a marker of nostalgia and parody, but also as a performative tool through which users negotiate identity, build communities, and share cultural memory. Rather than measuring dubbese against an ideal of linguistic realism, this article argues for recognising its value as an aesthetic and affective mode of communication.

Future research could explore how similar stylised dubbing languages operate in other cultural and linguistic contexts, and how they influence patterns of language use, humour, and identity construction in both online and offline spaces. Such work would deepen our understanding of the complex interplay between translation, media, and participatory digital cultures.

Acknowledgements/Funding

This work was supported by the Faculty Research Grant at Lingnan University (fund code 101944).

References

Antonini, R. (2008). The perception of dubbese: An Italian study. In D. Chiaro, C. Heiss, & C. Bucaria (Eds.), Between text and image updating research in screen translation (pp. 135–147). John Benjamins.

Baños, R. (2013). ‘That is so cool’: Investigating the translation of adverbial intensifiers in English-Spanish dubbing through a parallel corpus of sitcoms. Perspectives: Studies in Translatology, 21(4), 526–542.

Bilibili. (2024). https://search.bilibili.com/all?keyword=%E8%AF%91%E5%88%B6%E8%85%94&from_source=web_search

Blinn, M. D. (2009). Dubbed or duped? Path dependence in the German film market: An inquiry into the origins, persistence, and effects of the dubbing standard in Germany [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Freien Universität Berlin.

Boym, S. (2001). The future of nostalgia. Basic Books.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101.

Bruti, S., & Pavesi, M. (2008). Interjections in translated Italian: Looking for traces of dubbed language. In A. Martelli, & V. Pulcini (Eds.), Investigating English with corpora: Studies in honour of Maria Teresa Prat (pp. 207–222). Polimetrica.

Bucaria, C. (2008). Acceptance of the norm or suspension of disbelief? The case of formulaic language in dubbese. In D. Chiaro, C. Heiss, & C. Bucaria (Eds.), Between text and image updating research in screen translation (pp. 149–163). John Benjamins.

Bucaria, C., & Chiaro, D. (2007). End user perception of screen translation: The case of Italian dubbing. Tradterm, 13(1), 91–118.

Chaume, F. (2004). Cine y traducción. Cátedra.

Chaume, F. (2020). Dubbing. In Ł. Bogucki, & M. Deckert (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of audiovisual translation and media accessibility (pp. 103–132). Palgrave Macmillan.

Chen, X. (2023a). Danmu-assisted learning through back translation: Reception of the English-dubbed Journey to the West (Season II). Babel, 69(5), 598–624.

Chen, X. (2023b). The role of childhood nostalgia in the reception of translated children’s literature. Target, 35(4), 595–620.

Chen, X. (2023c). Interactive reception of online literary translation: The translator-readers dynamics in a discussion forum. Perspectives, 31(4), 690–704.

Chen, X. (2024). The role of spatial changes to paratext in literary translation reception: Eleven Chinese editions of Charlotte’s Web. Translation Studies, 17(2), 299–313.

Dawkins, R. (1976). The selfish gene. Oxford University Press.

Du, W. (2018). Exchanging faces, matching voices: Dubbing foreign films in China. Journal of Chinese Cinemas, 12(3), 285–299.

Duff, A. (1989). Translation. Oxford University Press.

Fang, K. (2020). Turning a communist party leader into an internet meme: The political and apolitical aspects of China’s toad worship culture. Information, Communication & Society, 23(1), 38–58.

Furno-Lamude, D., & Anderson, J. (1992). The uses and gratifications of rerun viewing. Journalism Quarterly, 69(2), 362–372.

Gal, N., Shifman, L. & Kampf, Z. (2016). “It gets better”: Internet memes and the construction of collective identity. New Media & Society, 18(8), 1698–1714.

Guo, M. (2018). Playfulness, parody, and carnival: Catchphrases and mood on the Chinese Internet from 2003 to 2015. Communication and the Public, 3(2), 134–150.

Hou, L., Jia, Y. & Li, A. (2012, September 9–13). Phonetic foreignization of mandarin for dubbing in imported western movies [Conference presentation]. 13th annual conference of the international speech communication association. https://www.isca-archive.org/interspeech_2012/hon12_interspeech.pdf

Hu, B. (2022). Feeling foreign: A trust-based compromise model of translation reception. Translation Studies, 15(2), 202–220.

Huntington, H. E. (2016). Pepper Spray Cop and the American dream: Using synecdoche and metaphor to unlock internet memes’ visual political rhetoric. Communication Studies, 67(1), 77–93.

Hutcheon, L. (2000). Irony, nostalgia, and the postmodern. In R. Vervliet, & A. Estor (Eds.), Methods for the study of literature as cultural memory (pp. 189–207). Rodopi.

Jiang, Y., & Vásquez, C. (2020). Exploring local meaning-making resources: A case study of a popular Chinese internet meme (biaoqingbao). Internet Pragmatics, 3(2), 260–282.

Jin, H. (2018). Introduction: The translation and dissemination of Chinese cinemas. Journal of Chinese Cinemas, 12(3), 197–202.

Jin, H., & Gambier, Y. (2018). Audiovisual translation in China: A dialogue between Yves Gambier and Jin Haina. Journal of Audiovisual Translation, 1(1), 26–39.

Katz, Y., & Shifman, L. (2017). Making sense? The structure and meanings of digital memetic nonsense. Information, Communication & Society, 20(6), 825–842.

Koskinen, K. (2000). Beyond ambivalence: Postmodernity and the ethics of translation. [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Tampere.

Kotze, H. (2024). Concepts of translators and translation in online social media: Construal and contestation. Translation Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/14781700.2023.2282581

Knobel, M., & Lankshear, C. (2007). Online memes, affinities, and cultural production. In M. Knobel, & C. Lankshear (Eds.), A new literacies sampler (pp. 199–227). Peter Lang.

Lanshiwendao. (2023). bilibili哔哩哔哩用户数据分析报告2023 [Bilibili user data analysis report 2023]. https://www.bilibili.com/opus/871540793858326567

Lu, Y. (2009, May 9). 上译厂老艺术家批明星配音 [The seasoned artists of the Shanghai Dubbing Studio criticise celebrity dubbing]. Yangtse Evening Post. https://www.chinanews.com/yl/kong/news/2009/05-09/1684180.shtml

Ma, Z. (2005). 影视译制概论 [An introduction to dubbing]. Communication University of China.

Ma, X. (2016). From internet memes to emoticon engineering: Insights from the baozou comic phenomenon in China. In M. Kurosu (Ed.), Human-computer interaction: Novel user experiences (pp. 15–27). Springer.

Pavesi, M. (1996). “L’allocuzione nel doppiaggio dall’inglese all’italiano.” In C. Heiss, R. Maria, & B. Bosinelli (Eds.), Traduzione multimediale per il cinema, la televisione e la scena (pp. 117–130). Clueb.

Pavesi, M. (2009). Pronouns in film dubbing and the dynamics of audiovisual communication. Vigo International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 6, 89–107.

Pavesi, M. (2016). Formulaicity in and across film dialogue: Clefts as translational routines. Across Languages and Cultures, 17(1), 99–121.

Pérez-González, L. (2007). Appraising dubbed conversation: Systemic functional insights into the construal of naturalness in translated film dialogue. The Translator, 13(1), 1–38.

Raitanen, J., & Oksanen, A. (2018). Global online subculture surrounding school shootings. American Behavioral Scientist, 62(2), 195–209.

Romero-Fresco, P. (2009). Naturalness in the Spanish dubbing language: A case of not-so-close Friends. Meta, 54(1), 49–72.

Ross, A. S., & Rivers, D. J. (2017). Digital cultures of political participation: Internet memes and the discursive delegitimization of the 2016 US presidential candidates. Discourse, Context & Media, 16, 1–11.

Sánchez-Mompeán, S. (2020). Prefabricated orality at tone level: Bringing dubbing intonation into the spotlight. Perspectives, 28(2), 284–299.

Scott, K. (2021). Memes as multimodal metaphors: A relevance theory analysis. Pragmatics & Cognition, 28(2), 277–298.

Shifman, L. (2011). An anatomy of a YouTube meme. New Media & Society, 14(2), 187–203.

Shifman, L. (2014). Memes in digital culture. The MIT Press.

Sun, Y. (2008). 一个有魅力的杂家 [A charming jack of all trades]. In X. Su (Ed.), 峰华毕叙:上译厂的四个老头儿 [Four gentlemen of Shanghai film dubbing studio] (pp. 30–36). Wenhui Press.

Taylor, C. (2020). Multimodality and intersemiotic translation. In Ł. Bogucki, & M. Deckert (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of audiovisual translation and media accessibility (pp.83–99). Palgrave Macmillan.

Varis, P., & Blommaert, J. (2015). Conviviality and collectives on social media: Virality, memes, and new social structures. Multilingual Margins, 2(1): 31–45.

Vásquez, C., & Aslan, E. (2021). ‘Cats be outside, how about meow’: Multimodal humor and creativity in an internet meme. Journal of Pragmatics, 171, 101–117.

Wang, Y (2017). 那些激荡人心的对白,我们曾倒背如流 [Those stirring lines: We once knew them by heart]. Wenhui. https://www.whb.cn/zhuzhan/jiaodian/20170331/88058.html

Wiggins, B. E. (2019). The discursive power of memes in digital culture: Ideology, semiotics, and intertextuality. Routledge.

Willmore, J., & Hocking, D. (2017). Internet meme creativity as everyday conversation. Journal of Asia-Pacific Pop Culture, 2(2), 140–166.

Yang, H., & Ma, Z. (2010). 当代中国译制 [Contemporary Chinese dubbing]. Communication University of China Press.

Zappavigna, M. (2012). Discourse of Twitter and social media: How we use language to create affiliation on the web. Bloomsbury Academic.

Data availability statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article (and/or its supplementary materials).

Disclaimer

The authors are responsible for obtaining permission to use any copyrighted material contained in their article and/or verify whether they may claim fair use.

∗ ORCID 0000-0002-4554-2861, e-mail: xuemeichen@ln.hk↩︎

Notes

The quoted reader comments are all my translations from Chinese, unless otherwise specified.↩︎