Quality in simultaneous interpreting with text: A corpus-based case study

Liuyin Zhao1 and Franz Pöchhacker2, University of Vienna

ABSTRACT

Simultaneous interpreting (SI) of read speeches using the speaker’s script in the booth (‘SI with text’) is a common practice, particularly in conferences of the United Nations (UN), but little is known about its effect on the quality of interpreters’ output. The present study investigates material from a corpus of authentic English–Chinese SI at a UN conference to establish whether SI with text is beneficial or detrimental to the quality of the interpretation, assessed for accuracy and completeness based on a graded (minor/major/critical) typology of non-correspondence as well as for target-language form and delivery. The corpus-based comparison between the two interpreting modes shows a ‘mixed’ effect of working with the script, with improvements in accuracy for details, such as names, numbers and terms, but a higher risk of critical information loss and a negative impact on fluency. The implications of these findings for interpreter-mediated multilingual communication in the world’s most important forum for international cooperation are discussed.

KEYWORDS

Conference interpreting, SI with text, quality, United Nations, corpus analysis.

1. Introduction

Simultaneous interpreting with text (SIT) is a mode of simultaneous interpreting (SI) in which the script from which a speaker reads is available in the booth, allowing the interpreter to rely on the written text and on auditory input. Whereas early scholars of conference interpreting (e.g., Déjean le Féal, 1982) held that SI worked best with impromptu speech and considered read speeches as intrinsically problematic, modern-day multilateral conferencing, especially in international organizations and high-stakes diplomacy, often involves carefully crafted manuscripts with high information density. This practice is particularly common in conferences of the United Nations (UN), where many speakers use a non-native language — typically English (e.g., Baigorri-Jalón & Travieso Rodríguez, 2017; Ruiz Rosendo & Diur, 2021). Reading from a script helps speakers achieve a proficient, literate style and communicate efficiently within often strict time limits. In the setting of multilingual conferences, the question arises whether relying on the script is helpful not only to speakers but also to the interpreters tasked with simultaneously rendering read speeches into other languages. In other words: Does the availability of the written text allow simultaneous interpreters to perform better than without having the speaker’s script? This question, which is at the heart of the present article, has been the subject of some theoretical analysis regarding the cognitive processes involved in SIT (e.g., Gile, 2009; Seeber, 2017) and has also been investigated in a small body of empirical research. Unlike these previous studies, which mostly rely on experimental data from student interpreters, we present a more ecologically valid approach in the form of a case study based on a larger corpus of professional SI at a real-life UN conference. Before engaging with the body of existing research (Section 1.2) and presenting our methodology (Section 2) and findings (Section 3), we will provide a more specific account of SIT as a complex mode of interpreting and discuss how it is practised and perceived in its most relevant institutional context – that is, conferences of the UN.

1.1. Conceptual and professional issues

The expression ‘simultaneous with text’ (‘SI with text’) is professional jargon that alludes to the commonplace assumption that a ‘text’ is something written. As Setton (2015, p. 385) points out, it is preferred over such terms as “sight interpreting” or “simultaneous sight translation,” since auditory input takes priority: “the interpreter must ‘check against delivery’ and, in the event of deviation, follow the speaker’s actual words rather than the text which has been provided.” This use of the term ‘text’ clashes with broader conceptions of text and discourse in language and communication studies (and translation studies), which go back at least to Beaugrande and Dressler’s (1981) notion of text as a “communicative event,” irrespective of its linguistic modality. Beyond the scholarly consensus that a text may be written or spoken (or signed), more recent theoretical accounts foreground the inherently multimodal nature of any text. Much more so than in (written) translation, this has special relevance to interpreting, where source texts include paraverbal and kinetic (‘embodied’) resources as well as verbal utterances (see Pöchhacker, 2021). Therefore, an interpreter’s input is multimodal and received in the acoustic as well as the visual channel even in ‘pure’ SI (without written text), as identified in Kumcu’s (2011, p. 49) classification of visual materials in SI. Adding written components to the input, which may range from bullet points on presentation slides all the way to a complete script, increases the complexity of receptive processes — as shown in Setton’s (1999) process model of SI and calculated in terms of cognitive load by Seeber (2017).

For the purpose of this article, the ‘text’ in SIT refers to a speaker’s full script, made available to interpreters beforehand so as to allow them to prepare. It does not include (verbal) presentation slides (though these may be used in addition to a script) nor real-time captions on a screen. Preparation thus becomes a salient factor, in at least two respects: (1) the opportunity to prepare largely determines the usefulness of the text to interpreters and hence the degree to which it can enhance their performance (see Setton, 2015, p. 386; Díaz-Galaz et al., 2015); and (2) the timely availability of the script to interpreters depends on speaker collaboration and document distribution efficiency. The latter are in place especially in institutions with well-established SI services, as exemplified by the UN family of organizations. Indeed, it is the context of UN conferences for which the practice of SIT has most often been described – as a highly taxing working mode that pushes professional interpreters to their limits, especially when speakers read fast and without proper intonation (see Barghout et al., 2015, p. 317). Sheila Shermet (2018), an experienced UN interpreter, speaks of “sight translation of complex written speeches” as standard practice, particularly in diplomatic meetings, suggesting that this forces interpreters to sacrifice grammatical elegance for the sake of close attention to detail. Likewise, an interpreter at New York headquarters responding to a survey reported by Baigorri-Jalón and Travieso-Rodríguez (2017, p. 64) felt “struck” by how much of their work “involves ‘sight translation’ of texts read at speed by delegates.” Working with the script was considered the norm, despite a sense that “it is not true interpreting, and does not facilitate communication.” Based on these perceptions of current practices, the question for the institution and the interpreting community is whether SIT serves “to maintain the high quality standards that have characterised United Nations interpreters’ performance since the origins of the organization” (2017, p. 63). Research on this issue to date is surprisingly limited.

1.2. Models and findings

In Gile’s (2009) model for SIT, reading is an additional “effort” competing for available “processing capacity.” Based on the assumption that interpreters usually work close to cognitive “saturation” even in regular SI, the model suggests a high risk of cognitive overload in SIT. The availability of additional visual input may aid listening comprehension and decrease the interpreter’s short-term memory load but require more effort to cope with the greater complexity of receptive and productive processes which results from the higher density written texts and the interference pressure exerted by source-language words and constructions. Seeber’s (2017) model of the “cognitive resource footprint” in SIT (p. 470) attempts to calculate cognitive demands with reference to “conflict coefficients”. As can be inferred from the interference score calculated for SI with visual input (not text) compared to that for SI (11.6 vs 9), the model suggests a distinctly higher cognitive load in SIT compared to SI without verbal-visual input. The model by Seeber et al. (2020) for audio-visual processing during reading, SI and SIT illustrates how the interpreter’s attention allocated to listening may interact with that allocated to reading, which ultimately affects the production of output.

The predictions of these theoretical models and the perceptions of professional conference interpreters working in this mode lead to two opposite assumptions regarding performance quality: on the one hand, SIT is likely to enhance accuracy and attention to detail, thanks to the availability of visual input; on the other hand, the complex processing mode may prove disruptive to formal correctness and fluent delivery. Empirical research to test these assumptions is sparse and often limited to experiments with interpreting students. While the focus and findings vary from study to study, the evidence overall points to positive as well as negative effects of SIT on the interpreter’s performance.

In one of the earliest studies on the topic, Lamberger-Felber (2003) investigated the effect of SIT on performance quality in an experiment with twelve experienced professionals, tasked to interpret three English conference presentations into German with or without the text and time for preparation. While she found that SIT, even without time for preparation, enhanced the interpreters’ accuracy in rendering numbers and proper names, her findings for “semantic correctness” and “completeness” (“errors and omissions”) were inconclusive, mainly as a result of high individual variability.

A much clearer positive effect on accuracy was found in Lambert’s (2004) experiment comparing sight translation to SI and SIT (allowing ten minutes’ preparation for a five-minute task). Matching the transcribed interpretations of 14 student participants (trained for three months in SI) against a written translation of the French source speech, she found significantly higher performance scores for the two with-text modes than for SI.

A few other experimental studies, also involving interpreting students with limited experience, yielded similar results. Spychała (2015) studied performance quality in (English–Polish) SI vs SIT more broadly in an experiment involving eight students. Listening-based analytical scoring by the author and four experienced raters confirmed the hypothesised superiority of SIT regarding accuracy for names and numbers as well as overall performance quality.

Accuracy, fluency and other delivery features were also assessed by Yang et al. (2020) in a study with 54 students (with at least one semester of SI training) performing SI either with or without the Chinese source text presented on a computer monitor without time for preparation. Based on the scores of two raters, visual access to the script was found to enhance overall quality. The students correctly rendered 31 out of 45 sentences in SI with on-screen text, compared to 28 without, and were also found to make fewer filled pauses.

Coverlizza (2004) compared ten students’ performances in English–Italian SI with and without text. The with-text condition, with ten minutes’ preparation for a 7.5-minute speech, contained four instances of the speaker deviating from the script. Transcripts, lightly annotated for some prosodic features, were scored for accuracy in rendering adjectival strings, enumerations and numbers. When working with the text, all but one participant did better in rendering adjectival strings and numbers, and all rendered the speaker’s personal memory (‘anecdote’), as opposed to none in SI without text.

On the negative side, Coverlizza’s (2004) study identified deviations from the script that resulted in (sentence-length) omissions and disfluencies. A detrimental effect of visual input in the case of deviations from the script was reported also in Pyoun’s (2015) experimental study with six professional interpreters (Korean–French), which focused on delivery features such as time lag and pointed to a more uneven performance in SIT.

In a well-controlled study involving 24 professional interpreters (English–Polish), Chmiel et al. (2020) focused specifically on the effect of incongruent input in the auditory and visual channels. Based on eye-tracking data and the interpreters’ rendering of 60 stimulus items (names, numbers, control words) in the manipulated source speech, they found greater reliance on the visual input, which therefore proved harmful to accuracy in the case of incongruence.

In summary, SIT, involving multimodal input in the acoustic and visual channels, is modelled as more complex a task than SI (Gile, 2009; Seeber, 2017). It is felt by professional interpreters to be more cognitively taxing but nevertheless necessary in order to cope with the demands of informationally dense speeches read out from a script, often at high speed. Judging from the few comparative studies investigating the effect of SIT on interpreters’ performance quality, this complex working mode seems to offer a clear advantage for accuracy while raising some doubts concerning the quality of delivery. The evidence base is however tenuous and inconsistent and does not allow definitive conclusions. Most of the findings are derived from laboratory experiments with students, often conducted in the context of Master’s theses. Even where experienced professionals were involved (e.g., Lamberger-Felber, 2003; Pyoun, 2015), research designs show little regard for ecological validity, so that available findings tell us very little about the quality of SIT in an authentic institutional and professional context. Our study breaks new ground in this regard by adopting a corpus-based comparative approach to examining SIT in an authentic and professionally relevant setting with experienced conference interpreters performing SI under typical working conditions.

The study seeks to establish whether there is a difference in SI performance quality, with regard to content, form and delivery, when the interpreter renders a read-aloud speech with or without the script available in the booth. Based on theoretical predictions and previous empirical findings, we hypothesise that SIT improves the interpreter’s performance quality on content (i.e., accuracy, completeness) but not necessarily on aspects of target-language form (e.g., lexis, syntax) and delivery (e.g., fluency, intonation).

2. Methodology

In order to answer our research question for SIT ‘in the field’ under real-life conditions, our study takes a corpus-based approach as a starting point for a comparative case study which relies on audio recordings complemented by observational fieldwork and document analysis.

Beyond the well-known obstacles to gaining access to authentic interpreter-mediated events and professional interpreters’ performances for research purposes (see Bendazzoli, 2016), corpus-based research on SIT faces a limitation that is typical of this line of research (e.g., Russo et al., 2012) — that is, the lack of information about the availability of the script in the booth and about its use by the speaker and the interpreter. In the absence of the necessary meta-data and documentation, a corpus-based approach requires a complementary fieldwork component in the collection of corpus data. These need to comprise not only recorded speeches and interpretations along with their transcriptions but also the actual scripts made available to the interpreters as well as information about the way the scripts are used. This approach was adopted for the present study (Section 2.1) and led to yet another methodological challenge: While read speeches — predominantly in English — were in plentiful supply in the conference proceedings used to compile the corpus, read speeches without the script available in the booth were not. This made a corpus-wide comparison of SI with and without text impossible and necessitated a more focused design that we consider akin to a natural experiment (Dunning, 2012). In essence, this involves a preliminary examination of the corpus for source speeches with comparable content-, form- and delivery-related characteristics. Moreover, a within-subject design is required to eliminate interpreter-related variability. The source speeches thus identified (Section 2.2) can then serve as a matched condition in a comparative study in which a given interpreter performs SI and SIT under comparable conditions. The respective interpretations can then be assessed for content-, form- and delivery-related criteria (Section 2.3).

2.1. Corpus

The corpus data were collected during observational fieldwork by the first author at the Vienna headquarters of the UN (see Zhao, 2021). Data collection centred on two consecutive conference days (9–10 June 2016) of the 59th session of the UN Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space, the audio recordings of which are available on the website of the UN Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA, 2023). The dummy booth used for the observation was serviced by UN conference staff like the working booths adjacent to it, so that the delivery of printed documents (including speech scripts) could be monitored and documented.

The four half-day sessions included 66 speeches by national delegates. Forty-one of these were read aloud in English, and the manuscripts of 39 of them were made available to the interpreters beforehand. The corpus under analysis comprises the 41 read English speeches and their simultaneous interpretations into Chinese (the first author’s native language). The interpretations were produced by four interpreters in the Chinese booth (A, B, C and D) working different shifts. However, only Interpreters A and B worked with and without text.

All the 41 read English speeches were fully transcribed, using scans of the available manuscripts as a starting point. The manuscripts were checked against the audio recordings and amended to reflect actual delivery. The interpretations were transcribed manually and annotated for unfilled pauses using Praat (Boersma & Weenink, 2015) with a pause threshold of 0.3 seconds (see De Jong & Bosker, 2013; Tannenbaum et al., 1967). In addition, the transcribed interpretations were examined and annotated for formal and delivery features (Section 2.3).

2.2. Sampling and matching of speeches

2.2.1. Selection

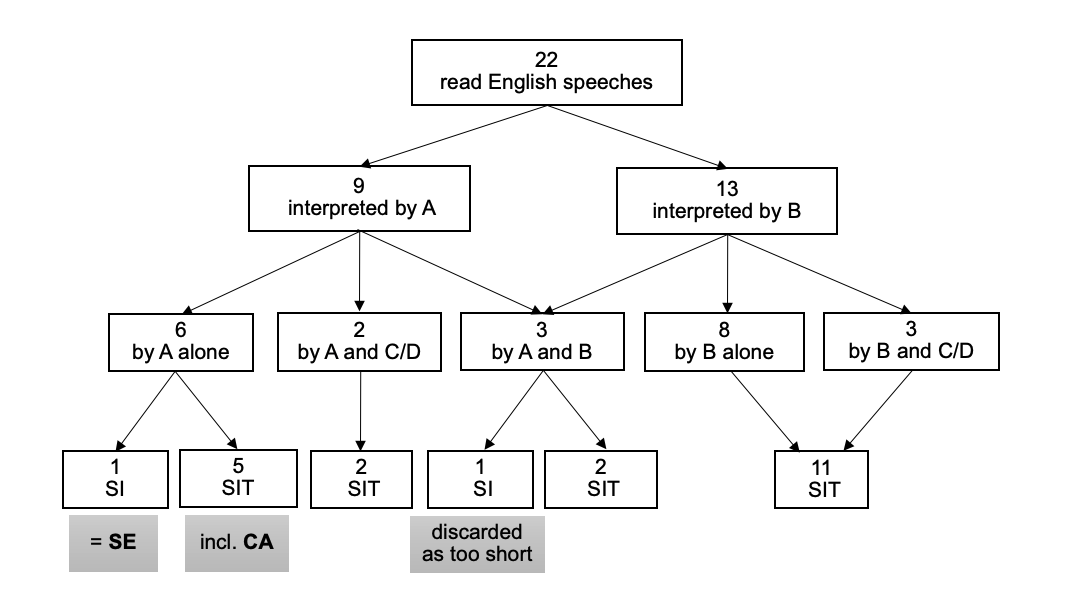

Out of the 22 speeches rendered by Interpreters A and B (see Figure 1), 17 had a length of 5–13 minutes (600–1500 words), the average being seven minutes (850 words), whereas the remaining five speeches lasted only two to three minutes.

Only two of the 22 speeches were interpreted without text. One of them, rendered by Interpreters A and B taking turns, was short (three minutes or 350 words). The other speech, by the (male) delegate of Sweden, was seven minutes long (1000 words), very similar in length to the average, and rendered solely by Interpreter A. This speech (referred to as ‘SE’) was chosen for comparison with SIT. For the purpose of our within-subject design, the SIT condition for comparison was sought among the other nine speeches rendered by Interpreter A with text.

These nine speeches were analysed regarding speed, pauses, intonation, terminology and syntactic complexity, after also checking the legibility of the scripts. Speech and articulation rates were calculated, and silent (unfilled) pauses were expressed in terms of frequency and speech-pause ratio. Besides these prosodic features, intonation (pitch variation) was assessed through a pre-written Praat script3 and expressed as the standard deviation from the speaker’s mean fundamental frequency. Linguistic analysis included the occurrence of outer space terminology, identified in consultation with an experienced terminologist, and the proportion of complex (composite) sentences.

Out of the nine speeches thus analysed, the one by the (female) delegate of Canada (referred to as ‘CA’) exhibited the greatest similarity with SE.

Figure 1. Breakdown of corpus speeches by interpreter and mode.

2.2.2. Comparative analysis

Both CA and SE were prepared as national statements, delivered with a native or near-native accent under the agenda item on international cooperation and long-term sustainability of outer space activities. Whereas CA is roughly 10% shorter in word count and duration than SE, it contains a higher proportion of both terms and complex sentences (Table 1). The two speeches are highly comparable on unfilled pauses but slightly different in speech rate. The female delegate from Canada exhibits significantly more pitch variation and hence a livelier intonation.

When compared to the other seven speeches rendered by Interpreter A, the values of SE and CA shown in Table 1 are largely similar concerning the proportion of terms (mean = 11%) and complex sentences (mean = 62%), the occurrence of disfluencies (e.g., voiced hesitation, syllable lengthening) as well as the proportion and duration of unfilled pauses (means = 24 and 15, resp.). The only criterion by which the two comparable speeches deviate significantly from the other speeches is speed: at roughly 150 words per minute (wpm), the speech rate of SE and CA is much higher than the average of 116 wpm found for the other seven speeches, which is in turn similar to the mean speech rate of 117 wpm in the 13 speeches rendered by Interpreter B. While the average speed of most speeches under study is therefore in line with the UN’s recommended rate of 120 wpm, the high speech rate of SE and CA, which constitutes a crucial similarity for our purposes, is also very typical of UN interpreters’ work (see, e.g., Ruiz Rosendo & Diur, 2021, p. 120).

SE and CA were delivered on 9 June 2016 in the middle of the morning session and near the end of the afternoon session, respectively; the corresponding scripts were made available in the booth one hour prior to the start of the sessions. Before rendering SE, Interpreter A had rested for 40 minutes while two boothmates were alternating with him. Before rendering CA, Interpreter A had also taken a 40-minute break, spoken for four minutes and then paused during an eight-minute video presentation for which no interpretation was provided.

| SE | CA | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Word count | 1024 | 944 | |

| Duration (seconds) | 416 | 363 | |

| Speech rate (wpm) | 148 | 156 | |

| Articulation rate (wpm) | 185 | 194 | |

| Proportion of terms (%) | 8 | 11 | |

| Proportion of complex sentences (%) | 65 | 74 | |

| Standard deviation of pitch (Hz) | 24 | 59 | |

| Voiced hesitation (instances per minute) | 0.4 | 0 | |

| Syllable lengthening (instances per minute) | 0 | 0.5 | |

| Unfilled pauses | Proportion (%) | 20 | 20 |

| Duration (seconds per minute) | 12 | 12 | |

| Frequency (instances per minute) | 15 | 11 | |

Table 1. Speeches by the delegates of Sweden (SE) and Canada (CA).

2.3. Quality assessment

Interpreter A’s interpretations of the comparable speeches (SE and CA were analysed regarding content, form and delivery — the three aspects of quality that have traditionally featured in schemes for assessing conference interpreters’ performance (see Moser-Mercer, 1996; Pöchhacker, 2001). The assessment of source–target correspondence with regard to content (see Pöchhacker, 2022, pp. 140-143) focused on accuracy and completeness; aspects of target-language form included mispronounced words, inappropriate lexical choices, and unusual syntax (i.e., sentence structure deviating from target-language norms); and delivery was assessed mainly concerning fluency (speed, pauses, hesitation, repetitions, repairs) and intonation.

2.3.1. Content

The degree of source–target correspondence was assessed using a clause-based approach. While reminiscent of the three types of “departures” introduced by Barik (1994), our assessment model is informed by the typology of renditions proposed by Wadensjö (1998), which includes close, expanded, substituted and reduced renditions. In addition, instances of non-correspondence are classified as either minor, major or critical, as in the NTR Model by Romero-Fresco and Pöchhacker (2017).

Using the source-speech segmentation performed to determine the proportion of complex sentences, the assessment procedure involved three main steps: first, each source-speech segment was compared to its target-language rendition and identified as either a close rendition or a case of non-correspondence; second, cases of non-correspondence were further classified as expanded, substituted or reduced renditions; and third, each classified instance was graded regarding the extent of non-correspondence as minor (i.e., not affecting the clause-level meaning), major (i.e., changing the clause-level meaning) or critical (i.e., severely distorting the clause-level meaning). All instances of non-corresponding renditions were counted and expressed as percentages of the total number of source-speech segments.

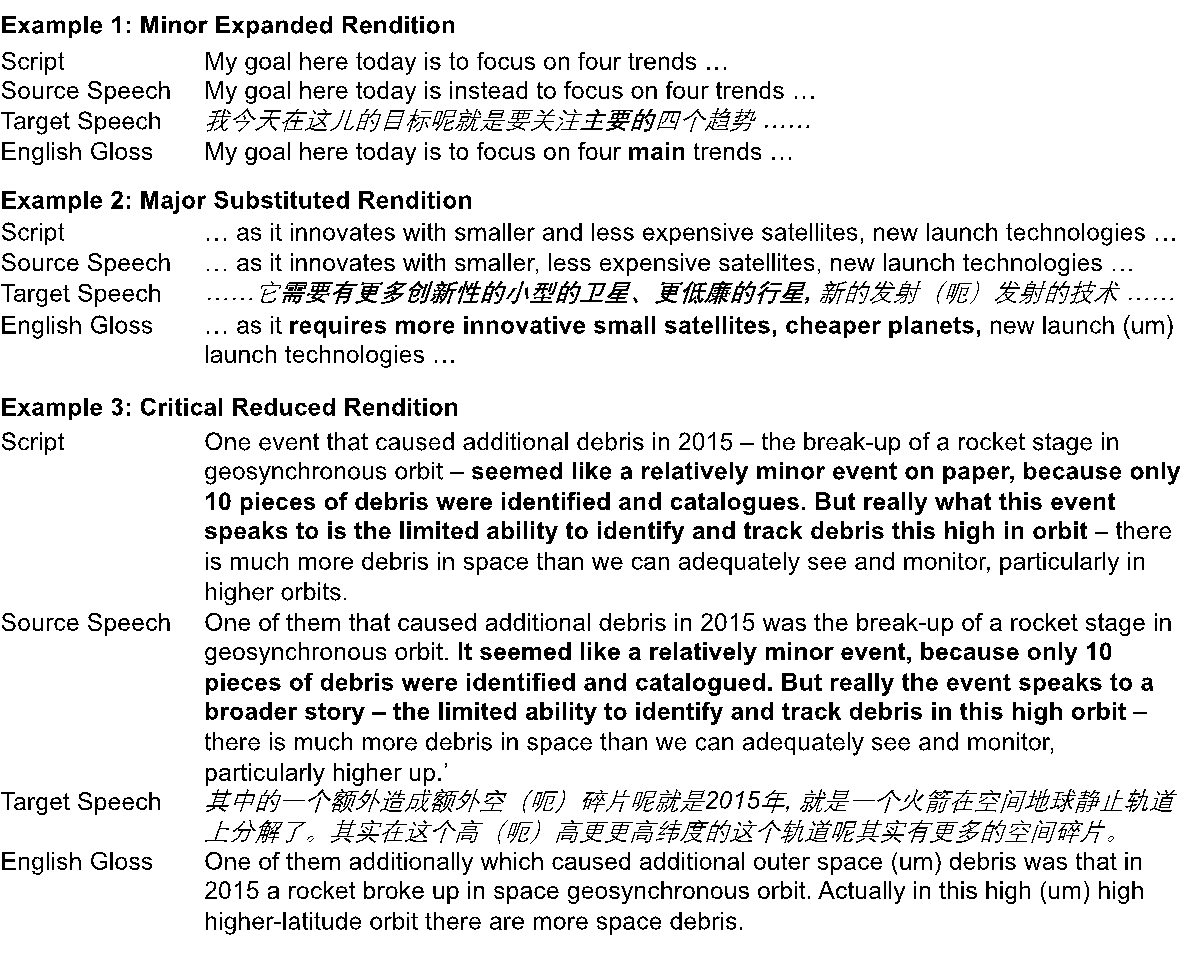

The examples from the corpus shown in Table 2 can serve to illustrate the graded assessment scheme for non-corresponding renditions.

Table 2. Examples of Interpreter A's rendering of CA.

In Example 1, the qualifier ‘主要的’ (main) is added to the interpretation. Since this addition does not change the meaning of the source-speech segment, it is classified as a minor expanded rendition.

In Example 2, the phrase ‘smaller, less expensive satellites’ is substituted with ‘小型的卫星、更低廉的行星’ (small satellites, cheaper planets), and ‘as it innovates with’ is replaced with ‘它需要有更多创新性的’ (as it requires more innovative). While clearly deviating from the original, this rendering does not completely distort the meaning of the source-speech segment and is therefore classified as a major substituted rendition.

In Example 3, the interpreter omitted a major chunk of the original that was written in the script and uttered by the speaker (as highlighted in bold). Since these parts of the source speech develop the idea conveyed in the previous segment and contain new content, their omission falls under the heading of critical reduced rendition. In other cases in this category, reduced renditions were found when the interpreter failed to render information that was not in the script but ad-libbed by the speaker.

Given the unavoidably subjective nature of this assessment, a second rater was asked to analyse the data. A native Chinese colleague with a Master’s degree in interpreting and nine years of professional experience was first trained in the application of the assessment scheme and then conducted the analysis independently. Based on Mellinger and Hanson (2017) and the suggestion by Riffe et al. (2019, p. 121) that “content analysis should report both a simple agreement figure and one or more reliability coefficients”, percent agreement and Krippendorff’s α were used to calculate the degree of consistency between the two assessments in general and the scores for individual types of renditions.

2.3.2. Form

The form-related features of the two interpretations were assessed with reference to Lee (2014). This involved the identification of any inappropriately formed or articulated words or clauses based on the transcripts and the recordings. Instances of mispronounced words and inadequate lexical choices were counted and expressed as percentages of the total number of words; the use of unusual syntax was expressed as a percentage of the total number of segments (clauses). The data was also analysed by the second rater in the same manner as described for content assessment.

2.3.3. Delivery

The assessment of the interpreter’s delivery was based on the same methods as used for the source speeches and included speed (speech rate, articulation rate), intonation (pitch variation) and unfilled pauses. In addition, unfilled pauses were subcategorised into long grammatical pauses (≥ 1.3 seconds) and non-grammatical pauses, and their frequency was calculated per minute. Likewise, the occurrence of filled pauses (voiced hesitation) and syllable lengthening was calculated per minute. Two further parameters of fluency, repairs and repetitions were identified in the transcripts and their frequency expressed per minute. Finally, the interpretations were also examined for the use of utterance-final particles (句末语气词). These are unstressed syllables typically used in spoken Chinese to express modality or register and may be assumed to be more frequent in spontaneous speech than in reading from a script.

3. Results

This section presents the findings of the analysis of Interpreter A’s performance in the two different working modes — that is, interpreting SE from auditory input only (SI) and interpreting CA with recourse to the text (SIT).

3.1. Content

With regard to the number of source-speech segments assessed as rendered accurately and completely, the interpreter’s performance was clearly superior in SIT. Out of the 105 segments comprising CA, 33 (31%) were classified as close renditions. In contrast, only 17% of the 123 segments making up SE were rendered closely.

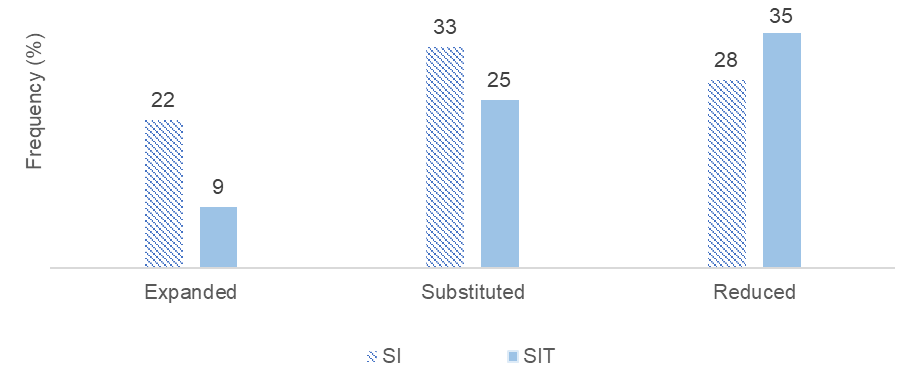

This preponderance of non-corresponding renditions in SI compared to SIT is mainly due to a higher number of expanded renditions. As Figure 2 shows, 22% of source-speech segments rendered in SI involved some form of expansion (addition), whereas this was the case in only 9% of the renditions in SIT. A similar but not equally pronounced difference is found for substituted renditions, which are distinctly more frequent in SI than in SIT. A reversal of this pattern is seen for reduced renditions, which are more frequent in SIT than in SI.

Figure 2. Comparison of non-corresponding renditions in SI and SIT.

When analysing the frequency of expanded renditions more closely regarding the degree of non-correspondence, most of them are found to be minor. All nine expanded renditions in SIT were minor, and only about one fifth of the additions in SI (six instances) were classified as major. There were no critical expanded renditions in either interpretation, and no additions in SIT were associated with information contained in the script but not uttered by the speaker.

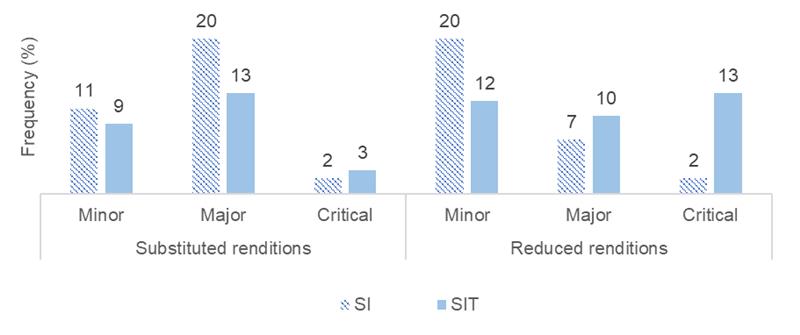

Substituted renditions, which had a higher share than expanded renditions in both interpretations and must be considered particularly relevant to accuracy, showed little difference in the category assessed as critical (Figure 3, left). The interpretations differed mainly on major substitutions, which were distinctly more frequent in SI than in SIT, whereas the percentage of minor substitutions was similar at around 10%.

The degree of completeness shows an entirely different pattern of results (Figure 3, right). While the interpretations are not too dissimilar regarding the share of reduced renditions classified as major, they differ markedly in minor ones and even more so in critical reduced renditions (omissions). Whereas there were only two cases of critical omission in SI, there were seven times as many in SIT. Several of these concerned the absence of any rendition (i.e., zero rendition, in the terminology of Wadensjö, 1998) for utterances not written in the script, but even more often the interpreter failed to render utterances that were also present in the script.

The reliability check performed on the first author’s quantitative findings by the independent reanalysis described above yielded a percent-agreement level of 84% for SI and 76% for SIT. Krippendorff’s α, at 0.81 for SI and 0.72 for SIT, was above the lowest acceptable benchmark of 0.67 (see Krippendorff, 2019). The highest levels of agreement were found for expanded renditions (87% for SI, 90% for SIT), and the two measures — percent agreement and Krippendorff’s α — were most similar between SI and SIT (77% vs 76% and 0.63 vs 0.64, resp.), albeit at a lower level, for the assessment of substituted renditions.

Figure 3. Comparison of substituted and reduced renditions in SI and SIT.

3.2. Form

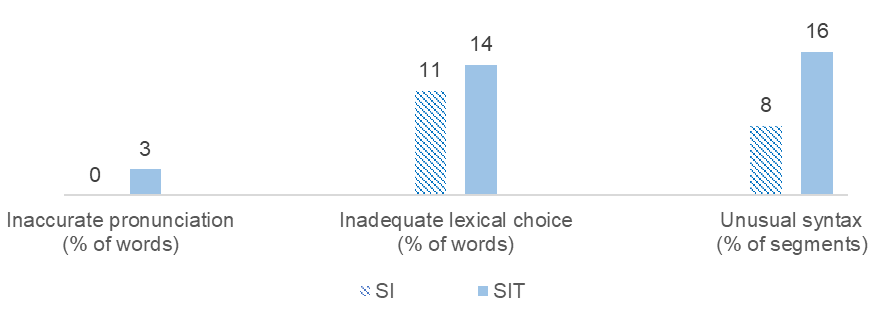

As shown in Figure 4, the three features assessed regarding target-language form were less frequent in SI than in SIT. Mispronunciation occurred only in SIT, where 3% of words were not articulated correctly. Inadequate lexical choices occurred in both interpretations but were somewhat more frequent in SIT. In SIT some of these cases were apparently due to source-language interference — that is, the use of a close Chinese equivalent with a misleading connotative meaning. Other instances of poor word choice, some of which in SIT and the vast majority in SI, involved unusual collocations or excessively literal, unidiomatic renditions. Moreover, the most pronounced differences in formal correctness were found for target-language syntax: the frequency of unusual syntactic constructions is twice as high in SIT as in SI.

Figure 4. Comparison of form-related features in SI and SIT.

3.3. Delivery

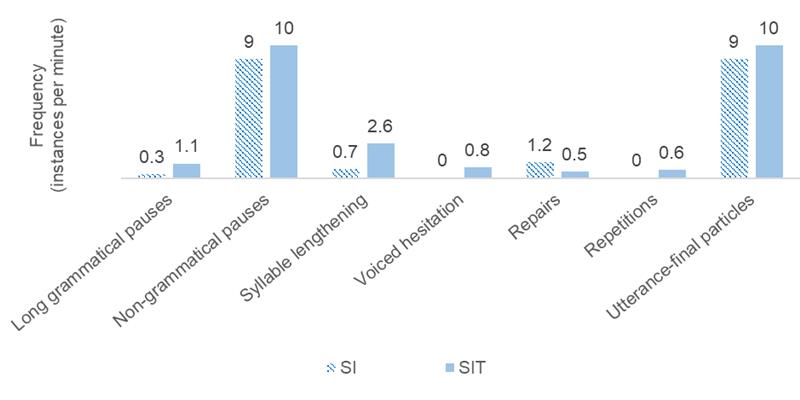

Although the speech rate of CA, rendered in SIT, was higher than that of SE, rendered in SI (Table 1), the interpreter’s speech rate in Chinese was lower in SIT (248 wpm) than in SI (274 wpm). However, the interpretation of CA also contained a larger proportion and duration of pauses than that of SE (17% vs 23%, and 14 vs 10 seconds per minute, respectively), so that the interpreter’s articulation rate in SIT (321 wpm) is lower than in SI (328 wpm) by only seven words per minute. In other words, the difference lies in the pause ratio rather than the delivery rate as such. Additionally, the interpreter’s pauses in SI were more frequent (17 vs 15 instances per minute) but shorter than in SIT.

More specifically, as Figure 5 shows, long grammatical pauses (≥1.3 seconds) were much more frequent in SIT than in SI. Similarly, unfilled pauses classified as non-grammatical were found more often in SIT than in SI. The same applies to hesitation: syllable lengthening occurred several times more often in SIT than in SI, and filled pauses (voiced hesitation), which were not detected in SI, occurred several times in SIT, as did repetitions. The only exception to this pattern in the findings for delivery parameters were repairs, which appeared more than twice as frequent in SI than in SIT. Utterance-final particles occurred in SI at a slightly lower rate than in SIT. On the other hand, intonation, expressed as the standard deviation of the interpreter’s mean fundamental frequency, was slightly lower in SIT (30 Hz) than in SI (32 Hz), suggesting that Interpreter A sounded slightly less lively in SIT than in SI. This finding can be substantiated by comparing Interpreter A’s intonation in the two interpretations to his mean pitch variation in those of the other seven speeches in SIT, which is exactly 30 Hz (range: 21–43). By the same token, Interpreter A’s mean pause time in these other speeches (15 seconds per minute) closely matches that found for his interpretation of CA (compared to ten seconds per minute when working in SI). The same applies to his mean frequency of long and of non-grammatical pauses when working in SIT (1.1 and 13 per minute, resp.) and to the other parameters of fluency: three lengthened syllables per minute; 0.3 filled pauses per minute; 0.5 repetitions per minute. All these mean values found for the other seven speeches in SIT closely match the values for CA but differ along the same lines from those in SE.

Figure 5. Comparison of delivery-related features in SI and SIT.

4. Discussion

Our study sought to answer the basic question whether conference interpreters tasked with simultaneously interpreting a read speech achieve a higher performance quality when using the script of the speech made available to them. Models of cognitive processing in SI (e.g., Gile, 2009; Seeber, 2017) suggest that SIT as a more complex mode of multimodal processing requires more attentional resources and may therefore put additional strain on the interpreter. According to Gile’s (2009) “tightrope hypothesis”, simultaneous interpreters are already working at the limit of their processing capacity, so that known “problem triggers” in the input speech such as high speed, technical terms and complex syntax could negatively affect performance quality and manifest themselves, for instance, in lower levels of accuracy or fluency. In addition, experimental studies, often with student interpreters rather than experienced professionals (e.g., Lambert, 2004; Spychała, 2015; Yang et al., 2020), have demonstrated that using the script can enhance the accuracy of the interpretation, sometimes but also compromise the interpreter’s delivery. Our findings confirm that working with the script has an impact on SI performance, regarding both the rendering of source-speech content (accuracy, completeness) and target-language form and presentation.

With regard to content, we had hypothesised that SIT would allow higher accuracy and completeness than SI. Our findings show a more complex pattern that can be summarised as follows: Working with the script, the interpreter indeed achieved a significantly higher percentage of close renditions (31%) than in SI from auditory input only (17%). This was mainly reflected in a lower number of (minor and major) expanded and substituted renditions, confirming the model-based prediction and earlier findings (e.g., Lamberger-Felber, 2001, 2003; Spychała, 2015) that SI with the visually present text allows greater accuracy for source-speech details such as numbers, names and terms. Regarding completeness, however, the interpreter omitted fewer details but more source-speech segments with important information when using the script. This higher risk of significant information loss in SIT was observed also by Lamberger-Felber (2001) and is likely due to the difficulty of attending to auditory and visual input in parallel and processing both sources with the same depth, especially when the speech is informationally dense and read at high speed. As shown by Chmiel et al. (2020), interpreters tend to give priority to the visual input. When the two input sources are incongruent — as in the case of ad-libbed utterances not found in the script — entire clauses may be lost, even though interpreters are obliged to ‘check against delivery’ and prioritise what they hear over what they see in the script. Moreover, focusing on the information in the script (i.e., primarily translating ‘at sight’) is likely to cause interpreters to follow the source text very closely, which may result in an excessive time lag. The interpreter’s efforts to catch up again with the speaker may then come at the cost of substantial omissions.

With regard to form, working with the script was found to be associated with a higher frequency of mispronounced words, inappropriate lexical choices and unusual target-language syntax. This is in line with earlier findings on the increased risk of lexical and syntactic interference in SIT (e.g., Lamberger-Felber & Schneider, 2008; Setton & Motta, 2007). Contrary to our expectations, the frequency of utterance-final particles was (slightly) higher in SIT than in SI. As regards all other aspects of form in our analysis, however, our hypothesis that using the script has an adverse impact on the quality of target-language expression was borne out by the compared data.

In similar vein, our findings clearly demonstrate an impact of SIT on the interpreter’s delivery quality. Whereas repairs were found to be more frequent in SI, where there is no guidance for speech planning from a written text, working with the script was associated with a higher frequency of filled pauses (‘um’) and syllable lengthening — that is, forms of hesitation that have been associated with higher cognitive processing loads (Plevoets & Defrancq, 2018). The same applies to the incidence of long pauses, non-grammatical pauses and repetitions, all of which are more frequent in SIT than in SI. Taken together with the slightly lower articulation rate found in SIT compared to SI, these findings confirm our hypothesis that SIT has a negative impact on the fluency of the interpreter’s delivery.

In summary, the pattern of findings in our comparison of performance quality in SI and SIT is ‘mixed’ in two ways: Overall, our hypothesis that SIT helps achieve greater accuracy but negatively affects target-language correctness and fluency is borne out by our quantitative analysis, confirming earlier suggestions (e.g., Cammoun et al., 2009) that using the script in SI for read speeches may be both a ‘friend’ and a ‘foe’. With regard to the accurate and complete rendition of source-speech content, however, the findings are equally mixed. Although the interpreter achieved a higher percentage of close renditions when using the script, this superiority was found to stem from a lower incidence of minor and major inaccuracies. In contrast, the frequency of reduced renditions of the major and especially the critical type was distinctly higher in SIT, suggesting a higher incidence of substantial information loss.

It is worth stressing that this rich pattern of findings for performance quality has been achieved thanks to the comprehensive and differentiated quality assessment scheme developed for this study. Rather than focusing on the rendering of specific source-text items, such as numbers and names, it comprises a broad range of quality-related parameters that cover information content as well as formal correctness and delivery. In particular, the interpretations were assessed for accuracy and completeness following a clause-based segmentation of the source speech, and any instances of informational non-correspondence were classified according to the degree to which the meaning of the source-speech segment was changed. This graded assessment, inspired by Romero-Fresco and Pöchhacker’s (2017) NTR Model, permitted the differentiation that revealed the crucial finding of more substantial meaning loss in SIT.

While the percentage of close renditions calculated in our assessment scheme may appear to be relatively low, it must be emphasised that most deviations from source–target correspondence are of a minor nature, as illustrated in Section 3.1. These findings therefore must not be understood as reflecting an insufficient degree of fidelity. Rather, the findings reflect an approach to interpreting that favours the rendering of sense over word-level translation, even though the latter may be favoured by the assessment scheme developed for this study.

Given our complex pattern of findings, the implications of our comparative study are not easy to formulate. Weighing up the promise of higher overall accuracy against the risk of some substantial information loss is invariably difficult, whether undertaken from the perspective of institutional employers (e.g., the UN), individual interpreters or end-users of interpreting services. Users, for instance, might attach greater importance to an interpreter’s fluent and pleasant delivery throughout a conference day; interpreters, however, may find working in SIT mode more strenuous and tiring but still unavoidable for the purpose of an accurate and detailed rendering, especially when speeches are informationally dense and delivered by reading at high speed.

Although our study focused on SI quality in relation to different working modes, our corpus-based analysis also offers valuable insights into the conditions that determine what Moser-Mercer (1996) referred to as “optimum quality”. Set in the real-life context of UN conferences, where SI in six languages has been offered for decades with well-developed institutional arrangements for staffing and document services, our study benefits from the high-level professionalism with which multilingual meetings in this institutional environment are conducted. Our corpus of authentic speeches and interpretations from a session of one of the UN’s many specialised bodies exemplifies what has been reported in the literature (e.g., Baigorri-Jalón, 2004; Baigorri-Jalón & Travieso-Rodríguez, 2017; Diur, 2015) about the prevalence of scripted speeches (typically in English) and the availability of scripts in the booth. Regarding the sensitive issue of speech rate, the analysis of the 22 speeches shows that most delegates to the conference under study delivered their (scripted) speech at a rate close to the UN’s recommended speed (120 wpm). Moreover, our corpus presents further evidence (beyond, e.g., Barghout et al., 2015) that UN conference speeches, including the two in our comparative analysis, are also delivered at much higher rates (above 150 wpm). It is under these circumstances that the speaker’s script in the booth may prove indispensable to achieving “optimum quality” in SI. In other words, our findings are based on source speeches that professional interpreters would find challenging. The UN interpreter in our study met this challenge in either working mode but achieved a higher rate of overall accuracy (close renditions) in SIT. It may well be the case that using the script for a speech delivered at a moderate or even slow speed would allow the interpreter to ensure a higher level of accuracy and completeness without necessarily affecting the correctness of his target-language expression or his fluency of delivery.

The use of a single level of source-speech speed may be considered one of the various limitations of our study based on a corpus of authentic speeches and interpretations. Additionally, our comparison is restricted to one interpreter. Although this interpreter is considered highly competent by UN standards, the results cannot be generalised to the larger population. Other limitations include the relatively small amount of material analysed, differences (e.g., accent, voice) in the two speeches used for comparison, the single language pair under study and the lack of precise data on the interpreter’s preparation and visual processing.

All of these are shaped by our choice of methodology, aside from practical considerations of feasibility. And it is this methodological approach in which we see the particular merit of our study. Over and above presenting the first comprehensive and differentiated assessment of performance quality in authentic SI with and without text, our study breaks new ground by combining a corpus-based analysis of authentic data with a comparative approach akin to a natural experiment. Since the former involved a significant ethnographic effort (on the part of the first author) and the latter largely hinged on what was found to be available by chance, our study is an innovative blend of corpus-based analysis, fieldwork and a case-based comparison. By combining the strengths of these different methodological strategies, including authenticity, quantification and matching of input-related variables, our study of SIT goes beyond the patchy set of findings from anecdotal reports, surveys and experiments involving student interpreters in laboratory situations.

5. Conclusion

SIT is a particularly complex working mode of simultaneous conference interpreters that has come to be predominant in such important institutional contexts as the UN. Nevertheless, interpreters’ performance in this highly relevant international setting has not attracted much systematic empirical research. Our study attempts to fill this gap by adopting an innovative methodological approach which capitalises on the authenticity of the setting and allows a considerable degree of matching of relevant variables in a case-based comparison. Our findings based on a graded assessment scheme largely confirm some previously held assumptions regarding improved accuracy in SIT but also highlight the greater risk of substantial information loss in SIT than in SI from auditory input only. Even so, they constitute only a first step toward more comprehensive corpus-based comparative research on SIT in different types of meetings and working conditions and different language pairs. Such corpus-based research should also be complemented by reception research among end-users of SI services so as to gauge the importance of formal correctness and fluent delivery from the listener’s perspective.

Our findings corroborate and extend previous literature on SIT, suggesting that using the speaker’s script in SI is both a help and a hindrance in achieving a high-level performance quality, but that there is little alternative for interpreters in such settings as UN conferences especially when speeches are read at high speed. Major changes to these established working practices may however be expected from ongoing efforts to develop computer-assisted interpreting (CAI) tools that provide interpreters with visual access to the source speech or source-speech elements through automatic speech recognition (e.g., Defrancq & Fantinuoli, 2021; Frittella, 2022; Prandi, 2023). Relying on the output of speech-to-text tools for source-speech details such as numbers, names and technical terms rather than on the complete script of the read-out speech could ease simultaneous interpreters’ cognitive processing load and allow them to give more attention to auditory input, thus reducing the risk of substantial information loss and presumably permitting a more correct, fluent and pleasant delivery.

Interpreters would still benefit from the availability of scripts for preparation – or for coping with strong accents or poor sound quality, but their working mode in SI would be more uniform, relying on CAI tools for specific written source-speech input (or even target-language equivalents) whether or not they have received the speaker’s script.

Acknowledgements

We thank Shanshan Xie for contributing to the reanalysis of data described in Section 2.3.

References

Baigorri-Jalón, J., & Travieso-Rodríguez, C. (2017). Interpreting at the United Nations: The impact of external variables. The Interpreters’ View. CLINA, 3(2), 53-72.

Baigorri-Jalón, J., (2004). Interpreters at the United Nations: A history. Universidad de Salamanca.

Barghout, A., Rosendo, L. R., & García, M. V. (2015). The influence of speed on omissions in simultaneous interpretation: An experimental study. Babel, 61(3), 305-334.

Barik, H. C. (1994). A description of various types of omissions, additions and errors of translation encountered in simultaneous interpretation. In S. Lambert, & B. Moser-Mercer (Eds.), Bridging the gap: Empirical research in simultaneous interpretation (pp. 121-137). John Benjamins.

Beaugrande, R.-A. de, & Dressler, W. U. (1981). Introduction to text linguistics. Longman.

Bendazzoli, C. (2016). The ethnography of interpreter-mediated communication: Methodological challenges in fieldwork. In C. Bendazzoli, & C. Monacelli (Eds.), Addressing methodological challenges in interpreting studies research (pp. 3-30). Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Boersma, P., & Weenink, D. (2015). Praat: Doing phonetics by computer, Version 5.4.21. http://www.praat.org/.

Cammoun, R., Davies, C., Ivanov, K., & Naimushin B. (2009). Simultaneous interpretation with text: Is the text “friend” or “foe”? Laying foundations for a teaching module. Master’s thesis, University of Geneva.

Chmiel, A., Janikowski, P., & Lijewska A. (2020). Multimodal processing in simultaneous interpreting with text: Interpreters focus more on the visual than the auditory modality. Target, 32(1), 37-58.

Coverlizza, L. (2004). L’interpretazione simultanea con e senza il testo scritto del discorso di partenza: Uno studio sperimentale. Master’s thesis, University of Bologna.

Defrancq, B., & Fantinuoli, C. (2021). Automatic speech recognition in the booth: Assessment of system performance, interpreters’ performances and interactions in the context of numbers. Target, 33(1), 73-102.

De Jong, N. H., & Bosker, H. R. (2013). Choosing a threshold for silent pauses to measure second language fluency. In R. Eklund (Ed.), Proceedings of the 6th workshop on disfluency in spontaneous speech (DiSS) (pp. 17-20). MPG. PuRe.

Déjean le Féal, K. (1982). Why impromptu speech is easy to understand. In N. E. Enkvist (Ed.), Impromptu speech: A symposium (pp. 221-239). Abo Akademi.

Díaz-Galaz, S., Padilla, P., & Bajo, M. T. (2015). The role of advance preparation in simultaneous interpreting: A comparison of professional interpreters and interpreting students. Interpreting, 17(1), 1-25.

Diur, M. (2015). Interpreting at the United Nations: An empirical study on the Language Competitive Examination (LCE). Doctoral dissertation, Universidad Pablo de Olavide.

Dunning, T. (2012). Natural experiments in the social sciences: A design-based approach. Cambridge University Press.

Frittella, F. M. (2022). CAI tool-supported SI of numbers: A theoretical and methodological contribution. International Journal of Interpreter Education, 14(1), 32-56.

Gile, D. (2009). Basic concepts and models for interpreter and translator training. John Benjamins.

Krippendorff, K. (2019). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Sage.

Kumcu, A. (2011). Visual focal loci in simultaneous interpreting. Master’s thesis, Hacettepe University.

Lamberger-Felber, H. (2001). Text-oriented research into interpreting: Examples from a case-study. Hermes, 26, 39-64.

Lamberger-Felber, H. (2003). Performance variability among conference interpreters: Examples from a case study. In Á. Collados Aís, M. M. Fernández Sánchez, & D. Gile (Eds.), La evaluación de la calidad en interpretación: Investigación (pp. 147-168). Comares.

Lamberger-Felber, H., & Schneider, J. (2008). Linguistic interference in simultaneous interpreting with text. In G. Hansen, A. Chesterman, & H. Gerzymisch-Arbogast (Eds.), Efforts and models in interpreting and translation research: A tribute to Daniel Gile (pp. 215-236). John Benjamins.

Lambert, S. (2004). Shared attention during sight translation, sight interpretation and simultaneous interpretation. Meta, 49(2), 294-306.

Lee, J. (2014). Rating scales for interpreting performance assessment. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer, 2(2), 165-184.

Moser-Mercer, B. (1996). Quality in interpreting: Some methodological issues. The Interpreters’ Newsletter, 7, 43-55.

Mellinger, C., & Hanson, T. (2017). Quantitative research methods in translation and interpreting studies. Routledge.

Plevoets, K., & Defrancq, B. (2018). The cognitive load of interpreters in the European parliament: A corpus-based study of predictors for the disfluency uh(m). Interpreting, 20(1), 1-28.

Pöchhacker, F. (2021). Multimodality in interpreting. In Y. Gambier, & L. Van Doorslaer (Eds.), Handbook of translation studies (pp.151-157). John Benjamins.

Pöchhacker, F. (2022). Introducing interpreting studies. Routledge.

Prandi, B. (2023). Computer-assisted simultaneous interpreting: A cognitive-experimental study on terminology. Language Science Press.

Pyoun, H. R. (2015). Paramètres quantitatifs en interprétation simultanée avec et sans texte. Forum, 13(2), 129-150.

Riffe, D., Lacy, S., Watson, B., & Fico, F. (2019). Analyzing media messages: Using quantitative content analysis in research. Routledge.

Romero-Fresco, P., & Pöchhacker, F. (2017). Quality assessment in interlingual live subtitling: The NTR model. Linguistica Antverpiensia, New Series – Themes in Translation Studies, 16, 149-167.

Ruiz Rosendo, L., & Diur, M. (2021). Conference interpreting at the United Nations. In M. Albl-Mikasa, & E. Tiselius (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of conference interpreting (pp. 115-125). Routledge.

Russo, M., Bendazzoli, C., Sandrelli, A., & Spinolo, N. (2012). The European parliament interpreting corpus (EPIC): Implementation and developments. In F. S. Sergio, & C. Falbo (Eds.), Breaking ground in corpus-based interpreting studies (pp. 53-90). Peter Lang.

Seeber, K. (2017). Multimodal processing in simultaneous interpreting. In J. W. Schwieter, & A. Ferreira (Eds.), The handbook of translation and cognition (pp. 461-475). Wiley Blackwell.

Seeber, K., Keller, L., & Hervais-Adelman, A. (2020). When the ear leads the eye: The use of text during simultaneous interpreting. Language, Cognition and Neuroscience, 35(10), 1480-1494.

Setton, R. (1999). Simultaneous interpretation: A cognitive-pragmatic analysis. John Benjamins.

Setton, R. (2015). Simultaneous interpreting with text. In F. Pöchhacker (Ed.), Routledge encyclopedia of interpreting studies (pp. 385-386). Routledge.

Setton, R., & Motta, M. (2007). Syntacrobatics: Quality and reformulation in simultaneous-with-text. Interpreting, 9(2), 199-230.

Shermet, S. (2018). United Nations interpreters: An insider’s view – Part 4. http://www.ata-divisions.org/ID/un-interpreters-an-insiders-view-4/.

Spychała, J. (2015). The impact of source text availability on simultaneous interpreting performance. Master’s thesis, Adam Mickiewicz University Poznań.

Tannenbaum, P. H., Williams F., & Wood, B. S. (1967). Hesitation phenomena and related encoding characteristics in speech and typewriting. Language and Speech, 10(3), 203-215.

UNOOSA (2023). Digital recordings. https://www.unoosa.org/oosa/audio/v3/index-staging.jspx.

Wadensjö, C. (1998). Interpreting as interaction. Longman.

Yang, S., Li, D., & Lei, V. L. C. (2020). The impact of source text presence on simultaneous interpreting performance in fast speeches: Will it help trainees or not? Babel, 66(4/5), 588-603.

Zhao, L. (2021). Simultaneous interpreting with text: A study in the context of the United Nations. Doctoral dissertation, University of Vienna.

Data availability statement

The audio recordings and transcripts used in the analysis of this study can be obtained upon request from the corresponding author. For legal reasons, the UN conference documents cannot be shared.

Disclaimer

The authors are responsible for obtaining permission to use any copyrighted material contained in their article and/or verify whether they may claim fair use.

* ORCID 0009-0007-9443-4991, e-mail: z.liuyin@icloud.com↩︎

** ORCID 0000-0002-8618-4060, e-mail: franz.poechhacker@univie.ac.at↩︎

Notes

https://github.com/FieldDB/Praat-Scripts/blob/main/draw_pitch_histogram_from_sound.praat. The script-generated data were randomly tested against those available from the Pitch menu of Praat, and were found to be consistent.↩︎